Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drought Sri Lanka

Project Report the Plan: Life-saving support to drought- affected children and their families by providing clean drinking water and food Where SRI LANKA What EMERGENCY RESPONSE Impact Increased access to safe water, provided essential food packages and raised awareness on good hygiene and sanitation practices during emergencies for 54,749 people, including 22,368 children. Your contribution has made a huge difference to the lives of children in Sri Lanka. Registered charity no: 276035 Emergency support for drought-affected children and families in Sri Lanka Ampara, Anuradhapura and Monaragala districts, Sri Lanka Final report Project summary Below average rainfall between March and November 2014 Sri Lanka: The Facts resulted in over 6 months of severe drought across certain areas of Sri Lanka; and in particular in the typically dry zones of the country, including the districts of Ampara, Anuradhapura and Monaragala. Initial assessments indicated that over 50,000 people across the three districts had been severely affected by the drought. Many families were living without clean drinking water and without reliable sources of food due to crop failure. Plan Sri Lanka developed a rapid and coordinated response taking into consideration the most urgent needs identified, gaps in provision from other humanitarian agencies and our expertise and potential reach in the affected areas. Plan’s two month response prioritised improving health by increasing access to safe water, providing essential Population: 21 million food packages and raising awareness on good hygiene and sanitation practices during emergencies. Infant Mortality: 17/1000 Life expectancy: 75 Through this emergency response, Plan has provided immediate and vital support to 54,749 people (27,795 Below the poverty line: 7% female), including 22,368 children. -

The Impact of Drought: a Study Based on Anuradhapra District in Sri Lanka Kaleel.MIM1, Nijamir.K2

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-2, Issue-4, July -Aug- 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijeab/2.4.87 ISSN: 2456-1878 The Impact of Drought: A Study Based on Anuradhapra District in Sri Lanka Kaleel.MIM1, Nijamir.K2 Department of Geography, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Oluvil Abstract— Anuradhapura District being one of the paddy in Anuradhapura Districts: Horovapothana, Ipolagama, providers in Sri Lanka highly affected due to the drought Nuwaragampalatha, Rambewa, Thirappana, disaster. The trend and cause for the drought should be Nachchathuwa, Palugaswewa, Kekirawa, identified for future remedial measures. Thus this study is Kahalkasthikiliya, Thambuthegama, Pathaviya, conducted based on the following objective. The primary Madavachchi and Kepatikollawa are the Divisional objective is that ‘identifying the impact of drought in Secretariats, highly affected. Anuradhapura District’ and the secondary objective are The impact of the drought occurrence should be ‘finding the direct and indirect factors causing drought controlled to pave a way for the agriculture and for the and the influence of drought in agriculture in the study socio economic development of inhabitants in area and proposing suggestions to lessen the impact of Anuradhapura. drought in the study area. To attain these objectives data from 1900 to 2014 were collected. All the data were II. STUDY AREA analysed and the trend of drought, condition of drought Anuradhpura District is situated in the dry zone of Sri and the impact of drought were identified. Many Lanka in the north central province of Sri Lanka. It has 22 suggestions have been provided in the suggestion part. -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Episodic Breakdown

World in Slow Motion, The 52 x 15 min’ EPISODIC BREAKDOWN 1. Ethiopia By Tuk Tuk 1 Arriving at Debre Zeyt, the team starts crossing the Ethiopian landscape in their three tuk tuks. After seeing their first African sunset and sleeping with a Hamer tribe, they head to Arba Minch. Here, as well as visiting a CIAI school project, they taste some traditional, local coffee, in the place where this beverage is said to have originated. 2. Ethiopia By Tuk Tuk 2 The group wakes up early to travel to Mago national park, where they meet the Mursi, an ancient tribe living deep in the heart of the park. The Mursi’s customs are fascinating, but their attitude to travellers and tourists isn’t quite what the team expects… 3. Ethiopia By Tuk Tuk 3 After meeting two piano players who literally play “on the road”, and hearing about their musical mission, the team arrives at a river, which they must decide whether or not to cross in order to witness the bull-hopping Hamer tribe ritual. The risk? That the water level rises, and that they don’t make it back! 4. Ethiopia By Tuk Tuk 4 The team finally reaches their destination: the river Omo. Now they must head back, stopping to visit a CVM project which hosts over 800 children, a CIAI project which teaches circus art to boys on the street and a marathon of over 40.000 people, which they decide to participate in. Their vehicles are worn and their legs are tired, but they only have a few more miles to go to complete their journey. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

Dress Fashions of Royalty Kotte Kingdom of Sri Lanka

DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA . DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KINGDOM OF SRI LANKA Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. Dedication First Edition : 2017 For Vidyajothi Emeritus Professor Nimal De Silva DRESS FASHIONS OF ROYALTY KOTTE KingDOM OF SRI LANKA Eminent scholar and ideal Guru © Dr. Priyanka Virajini Medagedara Karunaratne ISBN 978-955-30- Cover Design by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd Page setting by: Nisha Weerasuriya Published by: S. Godage & Brothers (Pvt) Ltd. 661/665/675, P. de S. Kularatne Mawatha, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka. Printed by: Chathura Printers 69, Kumaradasa Place, Wellampitiya, Sri Lanka. Foreword This collection of writings provides an intensive reading of dress fashions of royalty which intensified Portuguese political power over the Kingdom of Kotte. The royalties were at the top in the social strata eventually known to be the fashion creators of society. Their engagement in creating and practicing dress fashion prevailed from time immemorial. The author builds a sound dialogue within six chapters’ covering most areas of dress fashion by incorporating valid recorded historical data, variety of recorded visual formats cross checking each other, clarifying how the period signifies a turning point in the fashion history of Sri Lanka culminating with emerging novel dress features. This scholarly work is very much vital for university academia and fellow researches in the stream of Humanities and Social Sciences interested in historical dress fashions and usage of jewelry. Furthermore, the content leads the reader into a new perspective on the subject through a sound dialogue which has been narrated through validated recorded historical data, recorded historical visual information, and logical analysis with reference to scholars of the subject area. -

Genesis of Stupas

Genesis of Stupas Shubham Jaiswal1, Avlokita Agrawal2 and Geethanjali Raman3 1, 2 Indian Institue of Technology, Roorkee, India {[email protected]} {[email protected]} 3 Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology, Ahmedabad, India {[email protected]} Abstract: Architecturally speaking, the earliest and most basic interpretation of stupa is nothing but a dust burial mound. However, the historic significance of this built form has evolved through time, as has its rudimentary structure. The massive dome-shaped “anda” form which has now become synonymous with the idea of this Buddhist shrine, is the result of years of cultural, social and geographical influences. The beauty of this typology of architecture lies in its intricate details, interesting motifs and immense symbolism, reflected and adapted in various local contexts across the world. Today, the word “stupa” is used interchangeably while referring to monuments such as pagodas, wat, etc. This paper is, therefore, an attempt to understand the ideology and the concept of a stupa, with a focus on tracing its history and transition over time. The main objective of the research is not just to understand the essence of the architectural and theological aspects of the traditional stupa but also to understand how geographical factors, advances in material, and local socio-cultural norms have given way to a much broader definition of this word, encompassing all forms, from a simplistic mound to grand, elaborate sanctums of great value to architecture and society -

A Study About the Cognomens That Were Adopted by the Kings During Anuradhapura Era

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 10, Issue 1, January 2020 153 ISSN 2250-3153 A Study about the cognomens that were adopted by the kings during Anuradhapura Era Professor Anurin Indika Diwakara Department of Sinhala, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.10.01.2020.p9723 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.10.01.2020.p9723 Abstract: During the Anuradhapura Era the King was the head of the state. When studying inscription stones enlisted in this regard, what is clearly visible is the fact that, a reign based on heritance has been functioning. The kingship was deserved by those who hail from the Kshathriya dynasty. The amateur prince becomes a proper king after the coronation ceremony. In the absence of such coronation, the prince is not considered as the king of the state. In Mahavamsa Teeka, this is discussed at length. The one who commanded the entire governance system was the King, thus since the inception, a governance based on dynastic line was existed in ancient Sri Lanka. (Journal of the Royal Artistic Society of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1936, p.443.) Corpus Sri Lanka was so closely and intimately connected with India that every great change that took place in the main continent whether political, social, economic or religious influenced considerably the life of the people of Sri Lanka (Amaratunga G & Gunawardana N, 2019, Volume-3-issue6, 203-206). The king needs to be a secular, orderly person in his governance due to certain factors; those were to receive rain at apt time in favor of successful cultivation, to obtain prosperity and blessing for both citizens and the state, and for the smooth function of his governance with the help of citizens. -

Ports of the Ancient Indian Ocean Edited by MARIE-Frangoise

Ports of the Ancient Indian Ocean edited by MARIE-FRANgOISE BOUSSAC JEAN-FRANgOIS SALLES JEAN-BAPTISTE YON BCloKS Contents Editors' Note ix PROM THE RED SEA TO INDIA, THROUGH ARABIA AND THE PERSIAN GULF 1. The Egyptians on the Red Sea Shore during the Pharaonic Era 3 Pierre Tallet 2. Ship-related Activities at the Pharaonic Harbour of Mersa Gawasis 21 Cheryl Ward and Chiara Zazzaro 3. Living in the Egyptian Ports: Daily Life at Berenike and Myos Hormos 41 Roberta Tomber 4. Al-Shihr, an Islamic Harbour of Yemen on the Indian Ocean (AD 780-2007) 59 Ciaire Hardy-Guilbert 5. Indian Inscriptions from Cave Hoq at Socotra 79 Ingo Strauch 6. 'Places of Call' in Madagascar and the Comoros Terminology and Types of Settlement 99 Claude Allibert 7. The Port of Sumhuram: Recent Data and Fresh Reflections on its History 111 Alessandra Avanzini 8. Ports of the Indian Ocean: The Port of Spasinu Charax 125 Jean-Baptiste Yon vi Contents 9. Towards a Geography of the Harbours in the Persian Gulf in Antiquity (Sixth Century BC-Sixth Century AD) 137 Jean-Frangois Salles ANCIENT PORTS AND MARITIME CONTACTS OF INDIA 10. The Ports of the Western Coast of India according to Arabic Geographers (Eighth-Fifteenth Centuries AD): A Glimpse into the Geography 165 Jean-Charles Ducene 11. Ports of Western India in Latin Cartographic Sources, c. 1200 -1500: Toponymy, Localization and Evolutions 179 Emmanuelle Vagnon 12. Ancient Technology of Jetties and Anchorage System along the Saurashtra Coast, India 199 A.S. Gaur and Sundaresh 13. Bharuch Fort during the pre-Sultanate Period 217 Sara Keller 14. -

Thousand Years of Hydraulic Civilization Some Sociotechnical Aspects of Water Management

Thousand Years of Hydraulic Civilization Some Sociotechnical Aspects of Water Management H.A.H. Jayanesa1 and John S. Selker2 1. Department of Geology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. [email protected]; [email protected]; 94-81-2389156 (℡); 94-81-2224174(¬) 2. Department of Bioengineering, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA. [email protected]; 541-737-6304 (℡); 541-737-2082(¬) Abstract Sri Lanka had efficient hydraulic civilization for a period of thousand years from 200 BC till 1200 AD. Out of its 103 drainage basins, those underneath in the dry zone were successfully irrigated through system of tanks and diversion canals. Sociotechnical aspects of water management seem efficient and well performed in the construction and maintenance of these tank and canal systems. It is believed that the king and the regional chieftains perform very strong tight management. In addition strategic use of both top-down and bottom-up initiatives as well as private partnerships with their own tanks and maintenance systems were supported for the efficient maintenance and management. Though there are a number of contradictory points affecting the different ethnic and religious groups, the Dublin principles have been used at various decision-making stages by the present governments. However, the current political, economic and technical performances are not geared enough for such efficient water management. The religious, ethical and moral aspects interwove with the ancient civilization, were the basis for maintenance and management of the hydraulic systems and subsequent upheaval in the society. Therefore, we argued that for successful water resources development programs need community engagement, sound technology and timely resources. -

Shihan DE SILVA JAYASURIYA King’S College, London

www.reseau-asie.com Enseignants, Chercheurs, Experts sur l’Asie et le Pacifique / Scholars, Professors and Experts on Asia and Pacific Communication L'empreinte portugaise au Sri Lanka : langage, musique et danse / Portuguese imprint on Sri Lanka: language, music and dance Shihan DE SILVA JAYASURIYA King’s College, London 3ème Congrès du Réseau Asie - IMASIE / 3rd Congress of Réseau Asie - IMASIE 26-27-28 sept. 2007, Paris, France Maison de la Chimie, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme Thématique 4 / Theme 4 : Histoire, processus et enjeux identitaires / History and identity processes Atelier 24 / Workshop 24 : Portugal Índico après l’age d’or de l’Estado da Índia (XVIIe et XVIII siècles). Stratégies pour survivre dans un monde changé / Portugal Índico after the golden age of the Estado da Índia (17th and 18th centuries). Survival strategies in a changed world © 2007 – Shihan DE SILVA JAYASURIYA - Protection des documents / All rights reserved Les utilisateurs du site : http://www.reseau-asie.com s'engagent à respecter les règles de propriété intellectuelle des divers contenus proposés sur le site (loi n°92.597 du 1er juillet 1992, JO du 3 juillet). En particulier, tous les textes, sons, cartes ou images du 1er Congrès, sont soumis aux lois du droit d’auteur. Leur utilisation autorisée pour un usage non commercial requiert cependant la mention des sources complètes et celle du nom et prénom de l'auteur. The users of the website : http://www.reseau-asie.com are allowed to download and copy the materials of textual and multimedia information (sound, image, text, etc.) in the Web site, in particular documents of the 1st Congress, for their own personal, non-commercial use, or for classroom use, subject to the condition that any use should be accompanied by an acknowledgement of the source, citing the uniform resource locator (URL) of the page, name & first name of the authors (Title of the material, © author, URL). -

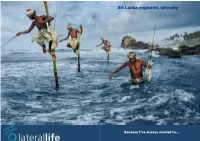

China Explored, Laterally

- Tim Bennett - China explored,Sri Lanka Laterally explored, - laterally Because I’ve always wanted to... Colombo = One way flight = Return flight = Drive = Train/Drive In a Nutshell... Flights... Date Airline & From Departs To Arrives Class Day 1 - Fly from London overnight Flight Number Day 2 - Arrive in Colombo. Rosyth Estate House SriLankan London Colombo Day 3 - 5 - At leisure. Rosyth Estate House Airlines Heathrow T3 Day 6 - Transfer to Ulagalla Resort, Anuradhapura SriLankan Colombo London Airlines Heathrow Day 7 - Anuradhapura by Bike. Ulagalla Resort T3 Day 8 - Morning Jeep Safari. Ulagalla Resort Day 9 - Train to Ella. Nine Skies Bungalow Day 10 - Explore Ella. Nine Skies Bungalow Trains... Day 11 - Transfer to Yala National Park. Chena Huts Day 12 - Explore Yala National Park on Safari. Chena Huts Day 13 - Morning Jeep Safari, transfer to Mirissa. Sri Sharavi Day 14 - Enjoy Sri Sharavi & Mirissa. Sri Sharavi Date From Departs To Arrives Class Day 15 - Morning Whale Watching from Mirissa. Sri Sharavi Day 16 - Enjoy Mirissa. Sri Sharavi Kandy TBC Nanu Oya TBC TBC Railway Station Railway Station Day 17 - Transfer to The Owl & The Pussy Cat, Koggala Day 18 - Galle Walking Tour. The Owl & The Pussy Cat Day 19 - Paddy Field Cycling Tour. The Owl & The Pussy Cat Day 20 - Transfer to Colombo, City Tour. Uga Residence Day 21 - Fly home Welcome home! Your Recommended Itinerary... Day 1 - Fly from the UK to Colombo overnight Today you will be collected from home by your chauffeur and driven to Heathrow Airport for your overnight flight to Colombo. Accommodation: Overnight flight Meals: On-board Meals Day 2 - Arrive in Colombo, transfer to Rosyth Estate, Kegalle You will be met at the airport by your laterallife representative and introduced to your chauffeur guide who will be accompanying you on your tour.