A Late Bronze Age Enclosure at Broomfield, Chelmsford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

Parish Church of St Peter, South Weald PARISH PROFILE

Parish Church of St Peter, South Weald PARISH PROFILE SEPTEMBER 2015 Our Church St Peter’s Church is in the village of South Weald on the outskirts of Brentwood, to the east of the M25 and the London Borough of Havering. It is a lively and flourishing church with a congregation encompassing all ages. Our services are middle of the road but there is a wide range of churchmanship within the congregation and our doors are open to all. More than half of the Electoral Roll live outside the parish. Our Voluntary Aided Primary School in the village has been rated as outstanding in all respects. We are fortunate to have a vibrant and diverse congregation, including a large number of young families. While many start to attend church in order to meet attendance criteria for admission to local church schools, our welcoming and accepting attitude means that a number become committed members of the congregation. Our challenge is to respect the needs of our long-standing members whilst engaging with newcomers. St Peter’s Rule of Life As followers of Christ, we aim: to attend worship regularly, including Holy Communion; to maintain a pattern of daily prayer and develop our spiritual lives; to read and study the Bible; to help grow the church community through our time, talents and money; to assist others and to serve the needs of the local community; to have a concern for the whole world and to work for the coming of God’s kingdom; 1 to share our faith through action and word. -

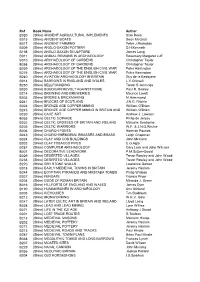

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

Authority, Reputation, and the Roles of Jeanne De Penthièvre in Book I of Froissart's Chroniques Journal of Medieval History

Authority, reputation, and the roles of Jeanne de Penthièvre in Book I of Froissart’s Chroniques Journal of Medieval History (forthcoming 2019: accepted manuscript) Erika Graham-Goering Department of History, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Abstract: This article examines how a medieval noblewoman’s positive reputation could be framed through different aspects of seigneurial power using a case study of Jeanne de Penthièvre and her war for the duchy of Brittany. Froissart wrote about Jeanne in the three main redactions of the first book of his Chroniques. However, he focused in the Amiens manuscript on her position as an heiress and the object of her followers’ loyalty, while the B text largely reduced her prominence but planted the seeds for the active military role Jeanne assumed in the Rome redaction. Such changes did not move strictly between more- or less- accurate reports, but engaged with different tropes that had also featured in the official portrayals of Jeanne during her lifetime. These parallel constructions of reputation reveal a plasticity to models of lordly authority even in rhetorical contexts more usually associated with formulaic and conventional representations of elite society. Article History: Received 16 May 2018. Accepted 5 July 2018. Keywords: Froissart, chronicle, reputation, rhetoric, Brittany, Jeanne de Penthievre, medieval women, lordship Rehabilitating the reputations of politically-active medieval women has meant that, in the past few decades, a growing body of scholarship has turned a much-needed critical eye to the process by which social mores, political interests, and iconic narratives could combine to create the ‘black legends’ that frequently transformed more-or-less typical noblewomen, and especially queens, into immoral caricatures. -

ECC Bus Consultation

Essex County Council ‘Getting Around in Essex’ Local Bus Service Network Review Consultation September 2015 Supporting Documentation 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Proposed broader changes to the way As set out in the accompanying questionnaire, Essex County Council (ECC) is undertaking ECC contracts for services that may also affect a major review of the local bus services in Essex that it pays for. These are the services that are not provided by commercial bus operators. It represents around 15% of the total customers bus network, principally in the evenings, on Sundays and in rural areas although some As well as specific service changes there are a number of other proposals which may do operate in or between towns during weekdays and as school day only services. This affect customers. These include: consultation does not cover services supported by Thurrock and Southend councils. • Service Support Prioritisation. The questionnaire sets out how the County Council will The questionnaire asks for your views about proposed changes to the supported bus in future prioritise its support for local bus services in Essex, given limited funding. network in your district. This booklet contains the information you need to understand This is based on public responses to two previous consultations and a long standing the changes and allow you to answer the questionnaire. Service entries are listed in assessment of value for money. This will be based on service category and within straight numerical order and cover the entire County of Essex (they are not divided by each category on the basis of cost per passenger journey. -

The Forty Plus Cycling Club Year 1989

The Forty Plus Cycling Club Year 1989 I FORTY PLUS CYCLING iCLUB. ; . I .. ! " ? • • ^ i i ^ '•• 'ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AT ThE jdKN MARSHALL PULL, ^CHRISTCHURCH INDUSTRIAL CENTRE, 27 BLACKFRIARS RE., iLONDONt S.E.I.. ON 28TH JANUARY 1989 AT 11.00 A.M. i AGENDA 1. Election of Chairnsan for the Meeting 2, ! ;Minuties of A.G.M. 30th January 1988, as published with "Signpost", ! Decenber 1988 3".! Matters Arising froE Minutes - i k. \ General Secretary's Report 5. Treasurer's Report (Statecient of Accounts overleaf) 6. Meabership Secretary's Report 7. •Proposed by the Committee To consider the granting of;- honorary oeabership to peKbbrs reaching 90 years of age 8. Proposed by the ConDittee:- That nieuibers' annual subscriptions . be raised to £2,50 for individuals! and to £3.00 for narried couples, : with computed subscriptions i aidjusted "pro rata I" 9. Proposed by Mrs. E. Paine Rule ^(B) - CoEiiPittee Meetings Seconded " W.O. Paine" That the words "in London" be deleted 10. Proposed by Mrs. E. Paine Rule 5(A) ~ Subscriptions . Seconded " Wi.0. Paine ThatthQ existing wording be repl^jced by the following "The:appropriate annual subscrip• tion shall be payable on 1st j January each year; this payiaeht to cover cecabership until 31st DeceDber of that year". 11 iElection of Officers for 1989 ;1. President 7. "Signpost" Editor 2. Chairaan 8. " Printer 3. General Sec. 9. " Distributor ,k, treasurer 10, " Address Typist 5. Membership Sec. 11; Runs List Typist :6. Auditor 12. Section Secretaries - Sussex South Beds St. Albans , I East Herts. • Stevenage v : Eastern/Northern 'A' ; Eastern/Northern 'B' . -

Revue De Presse « Défense » Date : 4 Décembre 2019 Prochaine Diffusion

Revue de presse « Défense » (contact : [email protected]) Votre avis nous intéresse : si vous voulez réagir à un article de la Revue de presse, vous pouvez soit contacter directement le responsable de thème de Défense soit réagir en adressant un courriel à l’adresse indiquée ci-dessus. L’équipe de la Revue de presse Défense vous remercie de votre confiance et de votre intérêt pour son travail, toutes vos suggestions sont les bienvenues. Cette revue de presse paraît désormais sur le site de l’UNION-IHEDN, à l’adresse : http://www.union-ihedn.org/les-actualites/revue-de-presse/ Aujourd'hui : Sainte Barbe - La revue de presse défense souhaite une bonne fête aux sapeurs, artilleurs, Sapeurs-pompiers, mineurs et ingénieurs militaires, aux camarades des essences, aux commandants des pétroliers, ainsi qu'aux camarades élèves et anciens élèves de l'Ecole polytechnique. Date : 4 décembre 2019 Prochaine diffusion : le mercredi 11 décembre 2019 Sommaire des articles proposés 1) Enjeux de la Défense, Doctrine, Concepts, Missions : • En mer Noire, un navire français joue au chat et à la souris avec les Russes • Réservistes de la gendarmerie : « Nos centres tournent à plein » 2) Relations internationales - Europe de la défense - OTAN : • Synthèse de l’actualité internationale de novembre 2019 • Une relation à sens unique – La France d’Emmanuel macron qui ignore l’Espagne de Pedro Sanchez • Ouïghours : les députés américains veulent des sanctions contre Pékin 3) Armements - Industries - Économie : • La France renonce à livrer six semi-rigides à -

Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.guten- berg.org/license Title: Brittany & Its Byways Author: Fanny Bury Palliser Release Date: November 9, 2007 [Ebook 22700] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BRITTANY & ITS BYWAYS*** Brittany & Its Byways by Fanny Bury Palliser Edition 02 , (November 9, 2007) [I] BRITTANY & ITS BYWAYS SOME ACCOUNT OF ITS INHABITANTS AND ITS ANTIQUITIES; DURING A RESIDENCE IN THAT COUNTRY. BY MRS. BURY PALLISER WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS London 1869 Contents Contents. 1 List of Illustrations. 7 Britanny and Its Byways. 11 Some Useful Dates in the History of Brittany. 239 Chronological Table of the Dukes of Brittany. 241 Index. 243 Transcribers' Notes . 255 [III] Contents. CHERBOURG—Mont du Roule—Visit of Queen Victoria—Har- bour, 1—Breakwater—Dock-Yard, 2—Chantereyne—Hôpi- tal de la Marine, 3—Castle—Statue of Napoleon I.—Li- brary—Church of La Trinité, 4—Environs—Octeville, 5—Lace- school of the Sœurs de la Providence, 11. QUERQUEVILLE—Church of St. Germain, 5—Château of the Comte de Tocqueville, 6. TOURLAVILLE—Château, 7—Crêpes, 11. MARTINVAST—Château, 12. BRICQUEBEC—Castle—History, 12—Valognes, 14. ST.SAUVEUR-le-Vicomte—Demesne—History, 15—Cas- tle—Convent—Abbey, 16. PÉRI- ERS, 17—La Haye-du-Puits, 17—Abbey of Lessay—Mode of Washing—Inn-signs, 18—Church, 19. -

Geology of London 1922.Pdf

F RtCELEY PR ART (JNIVERSI-.Y Of EARTH CALIFORNIA SCIENCES LIBRARY MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SUEVEY. ENGLAND AND WALES. THE GEOLOGY OF THE LONDON DISTRICT. (BEING THE AREA INCLUDED IN THE FOUR SHEETS OF THE SPECIAL MAP OF LONDON.) BY HORACE B. WOODWARD, F.R.S. SECOND EDITION, REVISED, BY C. E. N. BROMEHEAD, B.A., WITH NOTES ON THE PALAEONTOLOGY, BY C. P. CHATWIN. PUBLISHED P.Y ORDER OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF HIS MAJESTY'S TREASURY. ' LONDON: PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased from E. STANFORD, LTD., 12, 13, and 14, LONG ACRE, LONDON, W.C. 2; A. W. & K. JOHNSTON, LTD., 2, ST. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH ; HODGES, FIGGIS & Co., LTD., 20, NASSAU STREET, and 17 & 18, FREDERICK STREET, DUBLIN ; or from for the sale of any Agent Ordnance Survey Maps ; Qr through any Bookseller, from the DIRECTOR-GENERAL, ORDNANCE SURVEY OFFICE. SOUTHAMPTON. 1922. Price Is. Sd.^Net. MEMOIRS OF THE GEOLOGICAL SUEVET. ENGLAND AND WALESi V THE GEOLOGY OF THE LONDON DISTRICT. (BEING THE AREA INCLUDED IN THE FOUR SHEETS OF THE SPECIAL MAP OF LONDON.) BY HORACE B. WOODWARD, F.R.S. M SECOND EDITION, REVISED, BY C. E. N. BROMEHEAD, B.A., WITH NOTES ON THE PALAEONTOLOGY, BY C. P. CHATWIN. PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF HIS MAJESTY'S TREASURY. LONDON: FEINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased from E. STANFORD, LTD., 12, 13, and 14, LONG ACRE, LONDON, ^.C. 2; W. & A. K. JOHNSTON, LTD., 2, ST. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH ; HODGES, FIGGIS & Co., LTD., 20, NASSAU STREET, and 17 & 18, FREDERICK STREET, DUBLIN; or from for the sale of any Agent Ordnance Survey Maps ; or through any Bookseller, from the DIRECTOR-GENERAL, ORDNANCE SURVEY OFFICE. -

Olivier De Clisson Et La Société Politique Française Sous Les Règnes De Charles V Et De Charles VI

Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes Journal of medieval and humanistic studies Comptes-rendus | 2013 John Bell Henneman, Olivier de Clisson et la société politique française sous les règnes de Charles V et de Charles VI Vincent Challet Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/crm/12871 DOI : 10.4000/crm.12871 ISSN : 2273-0893 Éditeur Classiques Garnier Référence électronique Vincent Challet, « John Bell Henneman, Olivier de Clisson et la société politique française sous les règnes de Charles V et de Charles VI », Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes [En ligne], Comptes- rendus, mis en ligne le 28 janvier 2013, consulté le 15 octobre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/crm/12871 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/crm.12871 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 15 octobre 2020. © Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes John Bell Henneman, Olivier de Clisson et la société politique française sous... 1 John Bell Henneman, Olivier de Clisson et la société politique française sous les règnes de Charles V et de Charles VI Vincent Challet RÉFÉRENCE John Bell Henneman, Olivier de Clisson et la société politique française sous les règnes de Charles V et de Charles VI, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2011, 351p. ISBN 978-2-7535-1430-0 1 Paru en 1996 et seulement traduit en 2011, l’ouvrage de John Bell Henneman est parti d’une interrogation fondamentale : pourquoi donc, dans ses études si complètes de la société politique du royaume de France sous les règnes de Jean II et de Charles V, Raymond Cazelles n’a-t-il jamais évoqué la figure d’Olivier de Clisson ? Sans doute, répond l’auteur parce que ce seigneur breton, dont la devise était « Pour ce qu’il me plest », n’a jamais été membre du conseil royal, ce qui ne justifie pas pour autant qu’on doive nécessairement l’écarter d’une telle analyse. -

ESSEX L 2 ESSEX

• ESSEX is one of the metropolitan ,hil'es and takes its The Thames flows through London to the :Sorth Sea, name· from the commonwealth of the }:a:O;t .Saxons (one h;n-iug several quay~, but no great haven on the Essex • of tbe English hordes which settled in South Britain), shore, and the limits of the port of London extend to and of which Mid<lle;ex, London anu Hertfordshire after- . Haveugore creek in this county. The Lee, and its head, wards furmeu part. _\fter the }:usl<arrlian,; and Celts ' the Stort, are navigable, pa.;;sing through Bishop Stort had been driven out, }:s<e:>: was held by the Belgic tribe furd, Harlow and \Valtham Abbey; the Roding rises in of the Trinobantes until the Roman inroad. Of the 1 Easton Park, near Dunrnow, and flows south for about 36 Romans it wa_o; a great :seat and here wa.s- their city uf \ ntile,; past Ongar to llford, where it becomes- navigable, Camulodunun1. The 1\'Plch, again becoming nla.-;ters, ] and, pa~sing Barking, joins the 'l,hame~: the Bourne were driven out by the }~ast Saxon:-;. The chief dans ~ hrook, 12 n1iles long-, falls into the Than1es at Dagenham: concerned in the ~ettlen1ent u·ere the-· 'rilling, Halling, the Ingerbuurne rise5 in South lVeald and falls into the_ . Denning, Thnrring, BPmrin~, Billing, Htll'uing, ~Ianning, Than1es near Uainham: the Marditch, 12 mile3> long; Totting, Bucking- ~and lhumiug, being the smue as tlwse fo1·ms a creek at Purfieet: the Crouch, 25 miles long, engaged in the settlement of East .!uglia. -

Various Roads, Brentwood) (30Mph and 20Mph Speed Limit & Zone

The Essex County Council (Various Roads, Brentwood) (30mph and 20mph Speed Limit & Zone) Order 201* Notice is hereby given that Essex County Council proposes to make the above Order under Sections 84(1) (a) and (2) and Parts III & IV of Schedule 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. The effect of the Order: 1. To replace the existing 20mph speed limit with a 20mph zone on the following length of Hill Road, Hillside Walk and South Weald Road in the Borough of Brentwood: Road Description Hill Road For its entire length. Hillside Walk For its entire length. South Weald Road For its entire length. 2. To replace the existing 20mph zone with a 20mph speed limit on the following length of roads in the Borough of Brentwood: Road Description Belvedere Road For its entire length. Brook Road For its entire length. Honeypot Lane From its junction with the A1023 London Road in a generally northerly direction, for a distance of approximately 390 metres. Langley Drive For its entire length. Leonard Way For its entire length. Linkway Road For its entire length. River Road For its entire length. Selwood Drive For its entire length. Spital Lane From a point approximately 35 metres north of its junction with A1023 Brook Street in a generally northerly direction, for a distance of approximately 280 metres. Talbrook For its entire length. Tern Way For its entire length. The Grove For its entire length. Wansford Close For its entire length. Weald Close For its entire length. Wingrave For its entire length. Crescent Wingrave Court For its entire length.