Step out to Shadowtime, Hurry Like a Plant: Corporeal and Corporate Time for the Anthropocene Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law, Art, and the Killing Jar

Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 1993 Law, Art, And The Killing Jar Louise Harmon Touro Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/scholarlyworks Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 79 Iowa L. Rev. 367 (1993) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Law, Art, and the Killing Jart Louise Harnon* Most people think of the law as serious business: the business of keeping the peace, protecting property, regulating commerce, allocating risks, and creating families.' The principal movers and shakers of the law work from dawn to dusk, although they often have agents who work at night. 2 Their business is about the outer world and how we treat each other during the day. Sometimes the law worries about our inner life when determining whether a contract was made5 or what might have prompted a murder,4 but usually the emphasis in the law is on our external conduct and how we wheel and deal with each other. The law turns away from the self; it does not engage in the business of introspection or revelation. t©1994 Louise Harmon *Professor of Law, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, Touro College. Many thanks to Christine Vincent for her excellent research assistance and to Charles B. -

Tethered a COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album

Tethered A COMPANION BOOK for the Tethered Album Letters to You From Jesus To Give You HOPE and INSTRUCTION as given to Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois as well as Carol Jennings Edited and Compiled by Carol Jennings Cover Illustration courtesy of: Ain Vares, The Parable of the Ten Virgins www.ainvaresart.com Copyright © 2016 Clare And Ezekiel Du Bois Published by Heartdwellers.org All Rights Reserved. 2 NOTICE: You are encouraged to distribute copies of this document through any means, electronic or in printed form. You may post this material, in whole or in part, on your website or anywhere else. But we do request that you include this notice so others may know they can copy and distribute as well. This book is available as a free ebook at the website: http://www.HeartDwellers.org Other Still Small Voice venues are: Still Small Voice Youtube channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/claredubois/featured Still Small Voice Facebook: Heartdwellers Blog: https://heartdwellingwithjesus.wordpress.com/ Blog: www.stillsmallvoicetriage.org 3 Foreword…………………………………………..………………………………………..………….pg 6 What Just Happened?............................................................................................................................pg 8 What Jesus wants you to know from Him………………………………………………………....pg 10 Some questions you might have……………………………………………………….....................pg 11 *The question is burning in your mind, ‘But why?’…………………....pg 11 *What do I need to do now? …………………………………………...pg 11 *You ask of Me (Jesus) – ‘What now?’ ………………………….….....pg -

The Big Day) – Hopefully More Well-Received Than Chance the Rapper’S Ill-Conceived Paean to Loving His Wife by Kenji Shimizu

Festivus 2020: TBD (The Big Day) – Hopefully More Well-Received than Chance the Rapper’s Ill-Conceived Paean to Loving His Wife by Kenji Shimizu Note to players: Two answers required. 1. After declaring “I like my rock and roll all the same,” the singer declares that he doesn’t “give a fuck” if he does either of these two actions in “Back to the Motor League” by Propagandhi. Kurgan quotes a line mentioning these two actions in a church scene in Highlander, referencing a 1983 song’s spoken-word intro in which that line follows the gibberish phrase “Gunter glieben glauten globen.” In a 1979 album’s final track, the second half of a line about these two actions is replaced by the album’s title, (*) Rust Never Sleeps. That line about these two actions is quoted at the beginning of Def Leppard’s “Rock of Ages” and in the closing statements of Kurt Cobain’s suicide note. For 10 points, the song “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)” by Neil Young declares that “it’s better to” do what action “than to” do what other action? ANSWER: burn out and fade away [accept “It’s better to burn out than to fade away”] 2. In reference to a song titled after one of these people, the Martin guitar company embedded a coin into 73 limited-edition guitars to commemorate the victim of a September 1973 plane crash. The twist that Marie is the narrator’s six-year-old daughter is the final piece of information given to a person with this job in Chuck Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee.” The words of a person with this job are juxtaposed with several excuses given by Mrs. -

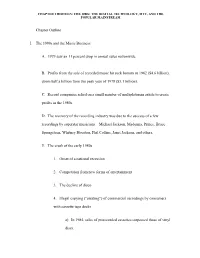

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM Chapter Outline I. The 1980s and the Music Business A. 1979 saw an 11 percent drop in annual sales nationwide. B. Profits from the sale of recorded music hit rock bottom in 1982 ($4.6 billion), down half a billion from the peak year of 1978 ($5.1 billion). C. Record companies relied on a small number of multiplatinum artists to create profits in the 1980s. D. The recovery of the recording industry was due to the success of a few recordings by superstar musicians—Michael Jackson, Madonna, Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Whitney Houston, Phil Collins, Janet Jackson, and others. E. The crash of the early 1980s 1. Onset of a national recession 2. Competition from new forms of entertainment 3. The decline of disco 4. Illegal copying (“pirating”) of commercial recordings by consumers with cassette tape decks a) In 1984, sales of prerecorded cassettes surpassed those of vinyl discs. CHAPTER THIRTEEN: THE 1980s: THE DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY, MTV, AND THE POPULAR MAINSTREAM F. New technologies of the 1980s 1. Digital sound recording and five-inch compact discs (CDs) 2. The first CDs went on sale in 1983, and by 1988, sales of CDs surpassed those of vinyl discs. 3. New devices for producing and manipulating sound: a) Drum machines b) Sequencers c) Samplers d) MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) G. Music Television (MTV) 1. Began broadcasting in 1981 2. Changed the way the music industry operated, rapidly becoming the preferred method for launching a new act or promoting a superstar’s latest release. -

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This Sheet Music Is Only Available for Use by ASU Students, Faculty, and Staff

Eldon Black Sheet Music Collection This sheet music is only available for use by ASU students, faculty, and staff. Ask at the Circulation Desk for assistance. (Use the Adobe "Find" feature to locate score(s) and/or composer(s).) Call # Composition Composer Publisher Date Words/Lyrics/Poem/Movie Voice & Instrument Range OCLC 000001a Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Original in E Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics 000001b Allah's Holiday Friml, Rudolf G. Schirmer, Inc. 1943 From "Katinka" a Musical Play - As Presented by Voice and Piano Transposed in F Mr. Arthur Hammerstein. Vocal Score and Lyrics by Otto A. Harbach 000002a American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000002b American Lullaby Rich, Gladys G. Schirmer, Inc. 1932 Voice and Piano Low 000003a As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000003b As Time Goes By Hupfel, Hupfeld Harms, Inc. 1931 From the Warner Bros. Picture "Casablanca" Voice and Piano 000004a Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004b Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000004c Ah, Moon of My Delight - In A Persian Garden Lehmann, Liza Boston Music Co. 1912 To words from the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" Voice and Piano Medium, F 000005 Acrostic Song Tredici, David Del Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. -

14.2 25Th Anniversary Issue •Fi Part 2

RAMPIKE 14/2 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INDEX Reed Altemus p. 2 Editorial p. 3 Joyce Carol Oates p. 4 Brian Henderson p. 9 Alistair MacLeod p. 10 Charles Bernstein p. 21 Roy Miki p. 27 George Elliott Clarke & Ricardo Scipio p. 28 Doug Barbour & Sheila Murphy p. 33 Michael Winkler p. 36 Antanas Sileika p. 40 Juris Kronbergs p. 42 Juri Talvet p. 45 Larissa Kostoff p. 50 Di Brandt p. 52 Una McDonnell p. 55 Jeff Gundy p. 56 Christopher Dewdney p. 57 Margaret Christakos p. 58 Andrew Bomberry p. 62 Rachel Zolf p. 63 Richard Douglas-Chin p. 64 Matthew Holmes p. 67 Stuart Ross p. 68 Robert Dassanowsky p. 70 rob mclennan p. 72 Carla Hartsfield p. 74 Bob Wakulich p. 78 Richard Scarsbrook p. 79 Carol Stetser p. 80 1 RAMPIKE 14/2 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 RAMPIKE 14/2 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL 25 Years in print! A cause for celebration! In this, our 25th anniversary issue (Part II), we continue our mandate by featuring both new and established postmodern artists, writers and thinkers. We open this issue with interviews featuring Joyce Carol Oates and Alistair MacLeod, two internationally acclaimed authors with links to the University of Windsor and Southwestern Ontario. This issue also features conceptual works by innovative thinkers including Brian Henderson, Matthew Holmes and Michael Winkler. These three reconsider the intimate connections -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking -

5.00 #211 April - June 2007

$5.00 #211 APRIL - JUNE 2007 ST. MARK’S CHURCH IN-THE-BOWERY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 www.poetryproject.com #211 APRIL-JUNE 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR Brendan Lorber IN THIS EPISODE... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Anselm Berrigan PROGRAM COORDINATOR Stacey Szymaszk PROGRAM ASSISTANT Corrine Fitzpatrick 5 FROM THE PAST MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszk 12, 33, 34 YEARS AGO IN THE NEWSLETTER WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Anselm Berrigan FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick SOUND TECHNICIANS Corrine Fitzpatrick, Arlo Quint, David Vogen 6 WORLD NEWS BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BREAKING REPORTS JUST IN FROM BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Stefania Iryne Marthakis, Erika Recordon BROOKLYN / THE CATSKILLS / HATTIESBURG INTERNS Kendall Grady, Sarah Kolbaskowski, Nicole Wallace IRAN / GRANADA / LJUBLJANA / LOS ANGELES VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, Jeremy Gardner, Ty PETALUMA / PHILADELPHIA / RUSSIA Hegner, Erica Kaufman, Evan Kennedy, Stefania Iryne Marthakis, Arlo Quint, Jessica TANGIER / TOKYO / VANCOUVER Rogers, Dgls Rothschild, Lauren Russell, Nathaniel Siegel, Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, Erica Wessmann, Sally Whiting 14 THE DIRECTOR LOOKS AROUND THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER is published four times a year and mailed free of charge to members of and contributors to the Poetry Project. Subscriptions A CONVERSATION WITH OUTGOING are available for $25/year domestic, $35/year international. Checks should be made ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ANSELM BERRIGAN payable to The Poetry Project, St. Mark’s Church, 131 East 10th St., NYC, NY 10003. The views and opinions expressed in the Newsletter are those of the individual authors and, while everyone in their right mind might be like, of course, duh!, they are not necessarily those of the Poetry Project itself. -

Songs in the Key of Z

covers complete.qxd 7/15/08 9:02 AM Page 1 MUSIC The first book ever about a mutant strain ofZ Songs in theKey of twisted pop that’s so wrong, it’s right! “Iconoclast/upstart Irwin Chusid has written a meticulously researched and passionate cry shedding long-overdue light upon some of the guiltiest musical innocents of the twentieth century. An indispensable classic that defines the indefinable.” –John Zorn “Chusid takes us through the musical looking glass to the other side of the bizarro universe, where pop spelled back- wards is . pop? A fascinating collection of wilder cards and beyond-avant talents.” –Lenny Kaye Irwin Chusid “This book is filled with memorable characters and their preposterous-but-true stories. As a musicologist, essayist, and humorist, Irwin Chusid gives good value for your enter- tainment dollar.” –Marshall Crenshaw Outsider musicians can be the product of damaged DNA, alien abduction, drug fry, demonic possession, or simply sheer obliviousness. But, believe it or not, they’re worth listening to, often outmatching all contenders for inventiveness and originality. This book profiles dozens of outsider musicians, both prominent and obscure, and presents their strange life stories along with photographs, interviews, cartoons, and discographies. Irwin Chusid is a record producer, radio personality, journalist, and music historian. He hosts the Incorrect Music Hour on WFMU; he has produced dozens of records and concerts; and he has written for The New York Times, Pulse, New York Press, and many other publications. $18.95 (CAN $20.95) ISBN 978-1-55652-372-4 51895 9 781556 523724 SONGS IN THE KEY OF Z Songs in the Key of Z THE CURIOUS UNIVERSE OF O U T S I D E R MUSIC ¥ Irwin Chusid Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chusid, Irwin. -

Music-Week-1993-05-2

4 RI pledge 6 IRightPrice 10 Pigswilifly 25 [ BBC radio chief 5 Our Price stores Green Jelly i!l sharpenn revamp focus to chartsingle success set for H iinsfflÊ week For Everyone in the Business of Music 29 MAY 1993 £2.65 Ensign rocked by exodus isEnsign shopping founder for aNigel new dealGrainge fol- eddiscussions parties. with two interest- EnsignTheir anddeparture its acts cornes from 18 differently,""The really he painful says. part for EnsignChrysalis had seven deals yearswith RCAago, lastlowing week his from surprise the label departure he has GraingeOver theand past Hill havetwo décadesbecome EMI'smonths takeover after the of completion Chrysalis. of artists,us is stepping especially away Sinead from andthe andthrough Island. Phonogram. It was launched runGrainge, for the pastA&R 17 years.manager respectedone of the A&R UK's teams. most Grainge highly EnsignGrainge has hadstresses a "broad-based that WorldGrainge, Party," Hill he adds.and Loader includesEnsign's Boo current Hewerdine, roster Bluealso erChris Doreen Hill Loaderand général left the manag- label Thinhas signed Lizzy andacts the ranging Boomtown from A&Rwith influence"Chrysalis, during where its it tiraehas comprisedstaff. No new Ensign's executives entire have Marie.Aéroplanes The label'sand Bufïystrongest St on Friday. Grainge, who sold Rats to Sinead O'Connor and retained its own office. "But yet been named to take over at EMIchart takeover. success came before the Ensign1986, is to nowChrysalis thought Records to bein edgedWorld Party.as one Hill of isthe acknowl- people thenow EMI the companyumbrella cornes we're underone of sidethe label, other which Chrysalis will sitiraprints along- Chrysalis managing director seeking a new label deal, possi- responsible for breaking black several A&R sources, predorai- suchCompulsion. -

The Duality of Portraiture in the Novels of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2012 'A Counterfeit Presentment': The Duality of Portraiture in the Novels of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy Sarah Catherine Ross College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Ross, Sarah Catherine, "'A Counterfeit Presentment': The Duality of Portraiture in the Novels of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 542. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/542 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘A Counterfeit Presentment’: The Duality of Portraiture in the Novels of George Eliot and Thomas Hardy A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in English from The College of William and Mary by Sarah Catherine Ross Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Deborah Morse, Adviser ________________________________________ Suzanne Raitt, Committee Chair ________________________________________ Brett Wilson ________________________________________ Charles Palermo Williamsburg, VA May 2, 2012 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..…… -

PDF Rendered Thu Nov 16 22:21:57 EST 2017

A. P. Schmidt Company Archives Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1994 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu017004 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2006577426 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: A. P. Schmidt Company Archives Span Dates: 1869-1958 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1891-1951) Call No.: ML31.A2 Creator: A.P. Schmidt Company Extent: 34,775 items ; 514 containers ; 280 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Arthur Paul Schmidt (1846-1921) was a German-born music publisher who pioneered the development and dissemination of American music. The A.P. Schmidt Company Archives documents his firm's publishing activites in Boston, Leipzig and New York, beginning with his tenure, through his successors, and until the firm was absorbed by Summy-Birchard in 1960. The Archives consists of the original manuscripts from which the music was printed, printed music, personal and corporate correspondence, photographs (primarily composers/arrangers), business records, plate books, publication books, stock and cash books. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Adams, Charles R. Apel, Willi, 1893-1988--Correspondence. Apthorp, William Foster, 1848-1913.