Department of Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfhi-Fcass.Ca | @Cfhi Fcass Discussion Panel

cfhi-fcass.ca | @cfhi_fcass Discussion Panel Jennifer Zelmer Dr. Rim Zayed Dr Moliehi Khaketla Dr. Nnamdi Ndubuka Dr. James Irvine CEO, Canadian Medical Health Officer Medical Health Officer Medical Health Officer Consultant Medical Foundation for Northern Population Northern Population Northern Inter-Tribal Health Officer, Healthcare Improvement Health Unit Health Unit Health Authority Northern Population Health Unit Jennifer Ahenakew Brian Quinn Robert St. Pierre Teddy Clarke Leonard Montgrand Executive Director of Nurse Senior Mayor of La Loche Chief of Clearwater River Métis Nation of Primary Epidemiologist Dene Nation Saskatchewan, Area Health Care, NNW, Northern Population Director SHA Health Unit COVID-19 Saskatchewan Northwest North Outbreak - Lessons Learned saskatchewan.ca/COVID19 June 29, 2020 VISION Healthy People, Healthy Saskatchewan MISSION We work together to improve health and well-being. Every day. For everyone. VALUES • SAFETY: Be aware. Commit to physical, psychological, social, cultural and environmental safety. Every day. For everyone. • ACCOUNTABILITY: Be responsible. Own each action and decision. Be transparent and have courage to speak up. • RESPECT: Be kind. Honour diversity with dignity and empathy. Value each person as an individual. • COLLABORATION: Be better together. Include and acknowledge the contributions of employees, physicians, patients, families and partners. • COMPASSION: Be caring. Practice empathy. Listen actively to understand each other’s experiences. PHILOSOPHY OF CARE: Our commitment to a philosophy -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

La Loche, Sask

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: ARSENE FONTAINE 1 INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: LA LOCHE, SASK. INTERVIEW LOCATION: LA LOCHE, SASK. TRIBE/NATION: CHIPEWYAN/FRENCH LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DATE OF INTERVIEW: JANUARY 21, 1983 INTERVIEWER: RAY MARNOCH INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: HEATHER BOUCHARD SOURCE: SASKATCHEWAN ARCHIVES BOARD TAPE NUMBER: IH-147 DISK: TRANSCRIPT 1a PAGES: 48 RESTRICTIONS: NO REPRODUCTION OF THE MATERIAL EITHER IN WHOLE OR IN PART MAY BE MADE BY ANY MEANS WHATSOEVER BY ANYONE OTHER THAN THE UNDERSIGNED, HIS HEIRS, LEGAL REPRESENTATIVES OR ASSIGNS, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION. HIGHLIGHTS: - Describes curing by a medicine man. - Brief description of how to make a canoe. - Description of transportation by dog team. i SUMMARY Christine and brother (William) Gordon had a store in Ft. McMurray and one in West La Loche. Adopted boy, George, from Edmonton. William died in 1932 and Christine soon after. George Gordon also died about 1975 but family still in McMurray today. They had a lot of land so they sold it and made lot of money. Although Christine said she was poor, a trunk full of money was found in her house. Arsene's dad, Baptiste Fontaine, was store manager for William Gordon in West La Loche. Brought supplies by canoe and wagon from McMurray. Baptiste was kind and helped people in hard times. Over in La Loche the people were poor; then Revillon built store there. The Hudson's Bay Company warehouse is now where the Revillon store was. There was no work in West La Loche. When back from trapping, they planted gardens then went by horse and canoe to work in McMurray at either the Bay warehouse or McInnis Fish Company. -

Canoeingthe Clearwater River

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | The clearwater river To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 1-2 weeks canoeing the clearwater river 105 km History of the Clearwater River For years fur traders from the east tried in vain to find a route to Athabasca country. Things changed in 1778, when Peter Pond crossed The legendary Clearwater has it the 20 km Methye Portage from the headwaters of the east-flowing all—unspoiled wilderness, thrilling Churchill River to the eventual west-bound Clearwater River. Here whitewater, unparalleled scenery was the sought-after land bridge between the Hudson Bay and and inviting campsites with Arctic watersheds, opening up the vast Canadian north. Paddling the fishing outside the tent door. This Clearwater today, you not only follow in the wake of voyageurs with Canadian Heritage River didn’t their fur-laden birchbark canoes, but also a who’s who of northern merely play a role in history; it exploration, the likes of Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson, changed its very course. John Franklin and Peter Pond. Saskatoon Saskatoon Regina Regina • Canoeing Route • Vehicle Highway Broach Lake Patterson Lake n Forrest Lake Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 955 A T ALBER Fort McMurray Clearwater River Broach Lake Provincial Park Careen Lake Clearwater River Patterson Lake n Gordon Lake Forrest Lake La Loche Lac La Loche Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 155 Churchill Lake Peter Pond 955 Lake A SASKATCHEWAN Buffalo Narrows T ALBER Skull Canyon, Clearwater River Provincial Park. -

Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1998 Aspect and the Chipewyan verb Bortolin, Leah Bortolin, L. (1998). Aspect and the Chipewyan verb (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/22542 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25896 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb by Leah Bortolin A THESIS SUBMI?TED TO THE FACULTÿ OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS CALGARY, ALBERTA February, 1998 O Leah Bortolin 1998 National Libmiy Bibiiothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disaibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. -

Blue Jay, Vol.27, Issue 2

THE METHY PORTAGE - PROPOSAL FOR A SASKATCHEWAN HISTORIC AND NATURE TRAIL by Henry T. Epp and Tim Jones, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon Methy Lake, La Loche Lake, Lac the area, with special attention paid La Loche, Methy Portage, Portage La to establishing what sorts of use were Loche—all of these are variant names made of the portage and what sorts for two geographical features found of human occupation of the La Loche in the northwest-central portion of area (if any) occurred in periods of Saskatchewan (see maps). These two the past more distant than the features are a lake and a long portage obviously busy early historic period both of which bore a great deal of the (Turner 1943). The information col¬ early traffic in furs and European lected in the few days we were able trade goods that passed through the to spend in the area indicates that fj whole of the American and Canadian artifactual material representing the northwest from the last decade or so Fur Trade or “proto-historic” period of the 18th century into even the first few years of the present one. Today the portage is more frequently called i the Clearwater Portage or the Clear- h water River Portage by the residents of the La Loche area. The History of the Portage i The importance of the Methy Por- tage during the Fur Trade period of m Canada’s history was great in com- B parison to various other portages be- 5- cause it was the shortest possible &j route crossing the height of land -■ dividing the vast drainage basins of the Churchill 'River isystem, which emp- 3 ties its waters ultimately into Hud- \t son Bay, and the Athabasca-Mackenzie ti drainage system, which flows into the Arctic Ocean. -

Summer 1996 Vol

Summer 1996 Vol. 23 No.2 Quarterly Journal of the Wilderness Canoe Association WESTWARD BOUND Kate Allcard The jaw of the RCMPwoman dropped. Her face held a various other rivers, go down the Mackenzie. blank, stunned look as she searched for something to I had decided that the first part of the Churchill, say. Finally she asked vaguely if I had a tent with me. where it flows into Hudson Bay, was too isolated, lt was spring 1995 and I was in Leaf Rapids, Mani- making it difficult to carry enough food. lt also looked toba, preparing to set out on a summer-long canoe trip like a lot of hard, upstream work. So here I was at Leaf and, being a responsible type, I was checking in with Rapids, excited and ready to go, undeterred by the RCMP to register the first leg of my journey to people's horror on hearing that I was headed upstream Pukatawagan. and alone. (I didn't dare tell them I figured on going all I, an English woman, had always wanted to accom- the way to Great Slave Lake.) plish a long solo canoe trip in Canada. Finally I had I pushed off on the evening of 30 May, having just saved enough money to buy my gear and realize my celebrated my 26th birthday. Most of the Churchill is ambition. Examining a map of Canada I had discovered made up oflakes with short stretches of river and rapids that the two longest rivers were the Churchill, running in-between. This first evening on Granville Lake was east, and the Mackenzie flowing north. -

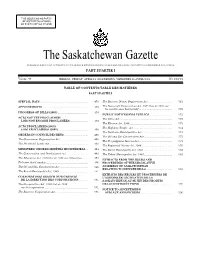

Sask Gazette, Part I, Apr 11, 2003

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART II (REVISED REGULATIONS) THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, APRIL 11, 2003 477 OR PART III (REGULATIONS) The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 99 REGINA, FRIDAY, APRIL 11, 2003/REGINA, VENDREDI,11 AVRIL 2003 No. 15/nº15 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I SPECIAL DAYS .................................................................. 478 The Business Names Registration Act ................................. 561 APPOINTMENTS ............................................................... 478 The Non-profit Corporations Act, 1995/Loi de 1995 sur les sociétés sans but lucratif .............................................. 572 PROGRESS OF BILLS (2003) .......................................... 478 PUBLIC NOTICES/AVIS PUBLICS ............................... 573 ACTS NOT YET PROCLAIMED/ The Cities Act ......................................................................... 573 LOIS NON ENCORE PROCLAMÉES ......................... 478 The Election Act, 1996 ........................................................... 573 ACTS PROCLAIMED (2003)/ The Highway Traffic Act ...................................................... 574 LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2003) ......................................... 480 The Northern Municipalities Act .......................................... 574 ORDERS IN COUNCIL/DÉCRETS ................................. 480 The Oil and Gas Conservation Act ...................................... -

La Loche, Sask. Tr

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: CHARLES JANVIER INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: LA LOCHE, SASK. INTERVIEW LOCATION: LA LOCHE, SASK. TRIBE/NATION: CHIPEWYAN/FRENCH LANGUAGE: CHIPEWYAN (SUMMARY IN ENGLISH) DATE OF INTERVIEW: JUNE 11 & 12/80 INTERVIEWER: VIOLET HERMAN & RAY MARNOCH INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: JOANNE GREENWOOD SOURCE: SASKATCHEWAN ARCHIVES BOARD TAPE NUMBER: IH-150/150A/151 DISK: TRANSCRIPT 1 PAGES: 6 RESTRICTIONS: NO REPRODUCTION OF MATERIAL EITHER IN WHOLE OR IN PART MAY BE MADE BY ANY MEANS WHATSOEVER BY ANYONE OTHER THAN THE UNDERSIGNED, HIS HEIRS, LEGAL REPRESENTATIVES OR ASSIGNS, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION. HIGHLIGHTS: - This document is a summary of the original interview in Chipewyan. Because the summarized sections are so short, they will be of little use to researchers, who may wish to refer to the original. EARLY LIFE: Mother, Adeline Maurice, daughter of H.B.Co. manager in West La Loche, her family French from Montreal. She died 4 days after Charlie was born. Charlie was raised by his grandparents, Pascal Janvier and Suzanne 'Birdsister'. Those were poor times. Charlie lived on boiled broth when a baby. No milk because his mother died. Later Charlie's Uncle Alex walked all the way to Fort Chipewyan to get a cow so baby Charlie could have milk. As a teenager Charlie worked for room and board at the H.B.Co.. When he was older he would travel by canoe to Big River 3 times a summer for H.B.Co. supplies. His father, Lacord Janvier, was married 3 times and had 26 children. His wives were Adeline, Isabelle and Sophie, a Cree from Ft. -

The Fish and Fisheries of the Athabasca River Basin

THE FISH AND FISHERIES OF THE ATHABASCA RIVER BASIN Their Status and Environmental Requirements Ron R. Wallace, Ph.D. Dominion Ecological Consulting, Ltd. and Peter J. McCart, Ph.D. Aquatic Environments Ltd. for Planning Division Alberta Environment March 31, 1984 PREFACE Thi s report was prepared by consul tants supervi sed by Bryan Kemper for Planning Division of Alberta Environment, and Dave Rimmer for Fish and Wildlife Division of Alberta Energy and Natural Resources. The Fisheries Overview series of reports have been commissioned to summarize known data to assist river basin planning studies and assist in the planning of new studies with the appropriate management agencies. The opinions expressed in this report are based upon written and verbal i nformati on provi ded to the consultant and therefore do not necessarily represent those of Alberta Environment. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The information presented here reviews what is currently known of fish ecology and production of the Athabasca Basin, and includes discussions of fish production, sport and commercial use of fish popul ati ons, and alternative opportuniti es for recreational fi shi ng in the rivers of the Athabasca Basin. Fisheries management objectives for the basin rivers and data gaps in existing knowledge of fish and fisheries are also discussed. In addition, water quality criteria for the protection of fish and aquatic life have been referenced, and, where possible, stream flows which affect fish populations have been included. The Athabasca Basin accounts for 23% of the land area of Alberta. For the purposes of this report, the basin has been divided into 10 sub-basins: four mainstem sub-basins, and six tributary sub-basins. -

The Social Landscapes of the Northwest / 23

One of the Family macdougall hi_res.pdf 1 1/14/2010 3:53:28 PM macdougall hi_res.pdf 2 1/14/2010 3:54:15 PM One of the Family Metis Culture in Nineteenth-Century Northwestern Saskatchewan brenda macdougall UBC Press • Vancouver • Toronto macdougall hi_res.pdf 3 1/14/2010 3:54:16 PM © UBC Press 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher, or, in Canada, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), www.accesscopyright.ca. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in Canada on FSC-certified ancient-forest-free paper (100% post-consumer recycled) that is processed chlorine- and acid-free. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Macdougall, Brenda, 1969- One of the family : Metis culture in nineteenth-century northwestern Saskatchewan / Brenda Macdougall. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-7748-1729-5 1. Métis – Saskatchewan – Île-à-la-Crosse – History – 19th century. 2. Métis – Kinship – Saskatchewan, Northern – History – 19th century. 3. Métis – Saskatchewan – Île-à-la-Crosse – Social life and customs – 19th century. 4. Métis – Saskatchewan, Northern – Social life and customs – 19th century. 5. Métis – Saskatchewan, Northern – Ethnic identity. 6. Fur trade – Saskatchewan, Northern – History – 19th century. 7. Catholic Church – Saskatchewan, Northern – History – 19th century. 8. Île-à-la-Crosse (Sask.) – Genealogy. I. Title. FC113.M33 2010 971.24’100497 C2009-903399-2 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. -

Wild Rivers: Saskatchewan

Indian and Affaires indiennes Northern Affairs et du Nord Wild Rivers: Parks Canada Pares Canada Saskatchewan Published by Parks Canada under authority of the Hon. Judd Buchanan, PC, MP, Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs. INA Publication No. QS-1458-000-EE-AI Design: Gottschalk+Ash Ltd. This and all other reports in the Wild Rivers series will also be available in French. Wild Rivers: Saskatchewan Wild Rivers Survey, Planning Division, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1974 2 Indians loading their canoes at a portage, 1873 (Public Archives of Canada) 3 It is difficult to find in life any event which so effectually condenses intense nervous sensation into the shortest possible space of time as does the work of shooting, or running an immense rapid. There is no toil, no heart breaking labour about it, but as much coolness, dexterity, and skill as man can throw into the work of hand, eye, and head; knowledge of when to strike and how to do it; knowledge of water and rock, and of the one hundred combinations which rock and water can assume-for these two things, rock and water, taken in the abstract, fail as com pletely to convey any idea of their fierce embracings in the throes of a rapid as the fire burning quietly in a drawing-room fireplace fails to convey the idea of a house wrapped and sheeted in flames. Sir William Francis Butler (1872) 4 ©Crown Copyrights reserved Soon to be available in this series: Available by mail from Information Wild Rivers: Alberta Canada, Ottawa, K1A 0S9 Wild Rivers: Central British Columbia and at the following Information Wild Rivers: Northwest Mountains Canada bookshops: Wild Rivers: Yukon Territory Halifax Wild Rivers: The Barrenlands 1683 Barrington Street Wild Rivers: The James Bay /Hudson Montreal Bay Region 640 St.