Blue Jay, Vol.27, Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cfhi-Fcass.Ca | @Cfhi Fcass Discussion Panel

cfhi-fcass.ca | @cfhi_fcass Discussion Panel Jennifer Zelmer Dr. Rim Zayed Dr Moliehi Khaketla Dr. Nnamdi Ndubuka Dr. James Irvine CEO, Canadian Medical Health Officer Medical Health Officer Medical Health Officer Consultant Medical Foundation for Northern Population Northern Population Northern Inter-Tribal Health Officer, Healthcare Improvement Health Unit Health Unit Health Authority Northern Population Health Unit Jennifer Ahenakew Brian Quinn Robert St. Pierre Teddy Clarke Leonard Montgrand Executive Director of Nurse Senior Mayor of La Loche Chief of Clearwater River Métis Nation of Primary Epidemiologist Dene Nation Saskatchewan, Area Health Care, NNW, Northern Population Director SHA Health Unit COVID-19 Saskatchewan Northwest North Outbreak - Lessons Learned saskatchewan.ca/COVID19 June 29, 2020 VISION Healthy People, Healthy Saskatchewan MISSION We work together to improve health and well-being. Every day. For everyone. VALUES • SAFETY: Be aware. Commit to physical, psychological, social, cultural and environmental safety. Every day. For everyone. • ACCOUNTABILITY: Be responsible. Own each action and decision. Be transparent and have courage to speak up. • RESPECT: Be kind. Honour diversity with dignity and empathy. Value each person as an individual. • COLLABORATION: Be better together. Include and acknowledge the contributions of employees, physicians, patients, families and partners. • COMPASSION: Be caring. Practice empathy. Listen actively to understand each other’s experiences. PHILOSOPHY OF CARE: Our commitment to a philosophy -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

La Loche, Sask

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: ARSENE FONTAINE 1 INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: LA LOCHE, SASK. INTERVIEW LOCATION: LA LOCHE, SASK. TRIBE/NATION: CHIPEWYAN/FRENCH LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DATE OF INTERVIEW: JANUARY 21, 1983 INTERVIEWER: RAY MARNOCH INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: HEATHER BOUCHARD SOURCE: SASKATCHEWAN ARCHIVES BOARD TAPE NUMBER: IH-147 DISK: TRANSCRIPT 1a PAGES: 48 RESTRICTIONS: NO REPRODUCTION OF THE MATERIAL EITHER IN WHOLE OR IN PART MAY BE MADE BY ANY MEANS WHATSOEVER BY ANYONE OTHER THAN THE UNDERSIGNED, HIS HEIRS, LEGAL REPRESENTATIVES OR ASSIGNS, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION. HIGHLIGHTS: - Describes curing by a medicine man. - Brief description of how to make a canoe. - Description of transportation by dog team. i SUMMARY Christine and brother (William) Gordon had a store in Ft. McMurray and one in West La Loche. Adopted boy, George, from Edmonton. William died in 1932 and Christine soon after. George Gordon also died about 1975 but family still in McMurray today. They had a lot of land so they sold it and made lot of money. Although Christine said she was poor, a trunk full of money was found in her house. Arsene's dad, Baptiste Fontaine, was store manager for William Gordon in West La Loche. Brought supplies by canoe and wagon from McMurray. Baptiste was kind and helped people in hard times. Over in La Loche the people were poor; then Revillon built store there. The Hudson's Bay Company warehouse is now where the Revillon store was. There was no work in West La Loche. When back from trapping, they planted gardens then went by horse and canoe to work in McMurray at either the Bay warehouse or McInnis Fish Company. -

Department of Linguistics

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb by Leah Bortolin A THESIS SUBMI?TED TO THE FACULTÿ OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS CALGARY, ALBERTA February, 1998 O Leah Bortolin 1998 National Libmiy Bibiiothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disaibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantiai extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be p~tedor otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. In the existing Athabaskan literature, the rnorphological and semantic properties of the imperfective and perfective prefbces, as weil as their distribution across the verb corpus, are not considered in any detail. The goal of this thesis is to gain a better understanding of the morphosemantic distribution of the five pairs of imperfective and perfective aspect prefxes in Chipewyan. -

Canoeingthe Clearwater River

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | The clearwater river To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 1-2 weeks canoeing the clearwater river 105 km History of the Clearwater River For years fur traders from the east tried in vain to find a route to Athabasca country. Things changed in 1778, when Peter Pond crossed The legendary Clearwater has it the 20 km Methye Portage from the headwaters of the east-flowing all—unspoiled wilderness, thrilling Churchill River to the eventual west-bound Clearwater River. Here whitewater, unparalleled scenery was the sought-after land bridge between the Hudson Bay and and inviting campsites with Arctic watersheds, opening up the vast Canadian north. Paddling the fishing outside the tent door. This Clearwater today, you not only follow in the wake of voyageurs with Canadian Heritage River didn’t their fur-laden birchbark canoes, but also a who’s who of northern merely play a role in history; it exploration, the likes of Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson, changed its very course. John Franklin and Peter Pond. Saskatoon Saskatoon Regina Regina • Canoeing Route • Vehicle Highway Broach Lake Patterson Lake n Forrest Lake Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 955 A T ALBER Fort McMurray Clearwater River Broach Lake Provincial Park Careen Lake Clearwater River Patterson Lake n Gordon Lake Forrest Lake La Loche Lac La Loche Preston Lake Clearwater River Lloyd Lake 155 Churchill Lake Peter Pond 955 Lake A SASKATCHEWAN Buffalo Narrows T ALBER Skull Canyon, Clearwater River Provincial Park. -

Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1998 Aspect and the Chipewyan verb Bortolin, Leah Bortolin, L. (1998). Aspect and the Chipewyan verb (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/22542 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25896 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Aspect and the Chipewyan Verb by Leah Bortolin A THESIS SUBMI?TED TO THE FACULTÿ OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS CALGARY, ALBERTA February, 1998 O Leah Bortolin 1998 National Libmiy Bibiiothéque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, disaibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fonne de microfiche/nim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. -

Saskatchewan and Manitoba Mining 2018

SASKATCHEWAN AND MANITOBA MINING 2018 AND MANITOBA SASKATCHEWAN SASKATCHEWAN AND MANITOBA MINING 2018 Policy Environment - Exploration and Production Technology and Services - Financing Dear Reader, Canada sets the tone of the global mining industry, given that 75% of mining companies are based in the country and it is among the top five producers of minerals globally. It is also the largest producer of potash in the world and the second-largest uranium producer after Kazakhstan. Canada’s uranium and potash resources are found in Saskatchewan; in fact, Saskatchewan has around 60% of global potash reserves and it accounted for 22% of the world’s primary uranium production in 2015. Manitoba, on the other hand, has significant base and precious metals resources, such as nickel, copper, zinc and gold, as well as lithium and cobalt. Whilst having a relatively underdeveloped mining industry compared to Saskatchewan, it accounts for 34% of Canada’s zinc production. However, mining production and investment have been slow in both provinces over the last few years, reflecting not only the global mining downturn, but low uranium and potash prices. Since the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011, uranium prices have been in a long decline, with U308 sitting at just US$21 per pound in April 2018, down from around US$65 per pound before the disaster. Potash prices have also fallen significantly in the last five to six years. However, there are hopes that Cameco’s decision to put its flagship McArthur River/Key Lake operations on standby in 2018 and Kazakhstan-based KazAtomProm’s reduction in production will shore up uranium prices. -

La Loche, Saskatchewan Interview Location

DOCUMENT NAME/INFORMANT: ARSENE FONTAINE #3 INFORMANT'S ADDRESS: LA LOCHE, SASKATCHEWAN INTERVIEW LOCATION: LA LOCHE, SASKATCHEWAN TRIBE/NATION: METIS LANGUAGE: ENGLISH DATE OF INTERVIEW: 01/28/80 INTERVIEWER: RAY MARNOCH INTERPRETER: TRANSCRIBER: HEATHER BOUCHARD SOURCE: SASKATCHEWAN ARCHIVES BOARD TAPE NUMBER: IH-149 DISK: TRANSCRIPT DISC #1a PAGES: 38 RESTRICTIONS: NO REPRODUCTION OF THE MATERIAL EITHER IN WHOLE OR IN PART MAY BE MADE BY ANY MEANS WHATSOEVER BY ANYONE OTHER THAN THE UNDERSIGNED, HIS HEIRS, LEGAL REPRESENTATIVES OR ASSIGNS, WITHOUT PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION. HIGHLIGHTS: - General reminiscences i SUMMARY MAIL: One man walked from Ile-a-la-Crosse, camped at Bull's House (north end of Peter Pond Lake). Next day ate at West La Loche and continued to Ft. McMurray via Clearwater R. He pulled a toboggan loaded with mail. Later Fred Daniels walked with mail to meet the train at 4:30p.m. in Alberta. He made trip in one day from West La Loche to Cheecham, Alberta. The mailman from Ft. McMurray to Ft. Chipewyan used dog team but Ile-a-la-Crosse man thought dogs too much trouble, walking was faster. Baptiste Herman from Christina, Alberta hauled freight from Cheecham by horse. He was always on time. Made two trips a month. Pay $72/month out of which he bought hay, oats, etc. Mail in summer from Ile-a-la-Crosse by canoe because there was no road. Cafe owner in Ft. McMurray, when poor, walked all over looking for jobs. Walked from McMurray to Prince Albert once and wore out nine pairs of moccasins on the trip. -

2017 Anglers Guide.Cdr

Saskatchewan Anglers’ Guide 2017 saskatchewan.ca/fishing Free Fishing Weekends July 8 and 9, 2017 February 17, 18 and 19, 2018 Minister’s Message I would like to welcome you to a new season of sport fishing in Saskatchewan. Saskatchewan's fishery is a priceless legacy, and it is the ministry's goal to maintain it in a healthy, sustainable state to provide diverse benefits for the province. As part of this commitment, a portion of all angling licence fees are dedicated to enhancing fishing opportunities through the Fish and Wildlife Development Fund (FWDF). One of the activities the FWDF supports is the operation of Scott Moe the Saskatchewan Fish Culture Station, which plays a Minister of Environment key role in managing a number of Saskatchewan's sport fisheries. To meet the province's current and future stocking needs, a review of the station's aging infrastructure was recently completed, with a multi-year plan for modernization and refurbishment to begin in 2017. In response to the ongoing threat of aquatic invasive species, the ministry has increased its prevention efforts on several fronts, including increasing public awareness, conducting watercraft inspections and monitoring high- risk waters. I ask everyone to continue their vigilance against the threat of aquatic invasive species by ensuring that your watercraft and related equipment are cleaned, drained and dried prior to moving from one body of water to another. Responsible fishing today ensures fishing opportunities for tomorrow. I encourage all anglers to do their part by becoming familiar with this guide and the rules and regulations that pertain to your planned fishing activity. -

Sakitawak Bi-Centennial

Soem Grises de Montreal D..".., Q All.":..t LO 1-1 Prepared by Robert Longpre Published by the ile-a-la-Crosse Bi-Centennial Committee lie-a-la-Crosse Local Community Authority January, 1977 Copyright held by the lie-a-la-Crosse Local Community Authority. All rights reserved , including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form other than brief excerpts for the purpose of reviews. (I) CREDITS .A. book of this type has many cooks. Than ks must be rendered to all who assisted in the material, the content, and the publication of this book. Thank You! Interviewer Janet Caisse , for interviews and translations to English of the recollections of Tom Natomagan, Claudia Lariviere, and Fred Darbyshire; Interviewer Bernice Johnson for interviews and translations to English of the recollections and stories of Marie Rose McCallum, Marie Ann Kyplain and Nap Johnson; Typist and proof-reader, Maureen Longpre, for the hours upon hours of work, typing and re -typing; Consultant and aide, Brian Cousins, for the direction and publication assistance; Photo collectors, Max Morin , Geordie Favel , Janet Caisse and T. J. Roy , for th e collection of photographs gathered, some of which appear on these pages ; lie-a-la-Crosse Mission, for the collection of photographs, the interviews, the access to books and the good will ; The Community of lie-a-la-Crosse , for helping to make this book come into print. Again Thank You! Robert Longpre November, 1976 Preparation of this publication has been a Bi-Centennial Project of lie-a-la-Crosse. It is our hope that this booklet will provide recognition and appreciation of our forefathers. -

A Son of My Father Final Print Working Copy

A Son of My Father Author Keith Koberinski Copyright © 2018 All rights reserved. ISBN: 13 A Son of My Father DEDICATION For My family for their encouragement and support. !2 A Son of My Father I HAVE NO IDEA WHERE THE WORDS COME FROM, OR WHERE THEY LEAD. I JUST WRITE AS THEY COME TO ME AND ALLOW THEM LEAD ME FORWARD. I WANT OTHERS TO KNOW ME THROUGH MY WORDS, AS DREAMER AT HEART, BURSTING WITH A LIFE I NEED TO SHARE, WITH ANYONE WILLING TO KNOW. KEITH KOBERINSKI 2017 !3 A Son of My Father CONTENTS CHAPTER Forward Pg 6 1 Where I Come From Pg 10 2 Youth Pg 22 3 Leaving Home Pg 33 4 On My Own Pg 38 5 Work Adventures Pg 50 6 Marriage - A New Pg 62 Beginning 7 Church Pg 70 8 Politics Pg 85 9 Family Pg 97 10 Sports Pg 108 11 Ordinary Time Pg 122 12 Be The Bridge Pg 132 13 Music and My Life Pg 137 14 Laughter And Pg 145 Caring 15 Where I Am Today Pg 155 16 The LastWaltz Pg 162 !4 A Son of My Father Forward These days I awake to a different world. For the first time since I can remember since childhood, I awake to a totally free day. For all of my seventy-five plus years, I have always been responsible to someone or something every day in some way or form. From learning how to walk, talk, attend schools, get a job, get married, raise kids and providing for them all were real responsibilities for me. -

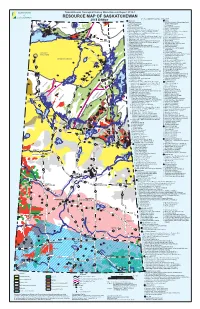

Mineral Resource Map of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan Geological Survey Miscellaneous Report 2018-1 RESOURCE MAP OF SASKATCHEWAN KEY TO NUMBERED MINERAL DEPOSITS† 2018 Edition # URANIUM # GOLD NOLAN # # 1. Laird Island prospect 1. Box mine (closed), Athona deposit and Tazin Lake 1 Scott 4 2. Nesbitt Lake prospect Frontier Adit prospect # 2 Lake 3. 2. ELA prospect TALTSON 1 # Arty Lake deposit 2# 4. Pitch-ore mine (closed) 3. Pine Channel prospects # #3 3 TRAIN ZEMLAK 1 7 6 # DODGE ENNADAI 5. Beta Gamma mine (closed) 4. Nirdac Creek prospect 5# # #2 4# # # 8 4# 6. Eldorado HAB mine (closed) and Baska prospect 5. Ithingo Lake deposit # # # 9 BEAVERLODGE 7. 6. Twin Zone and Wedge Lake deposits URANIUM 11 # # # 6 Eldorado Eagle mine (closed) and ABC deposit CITY 13 #19# 8. National Explorations and Eldorado Dubyna mines 7. Golden Heart deposit # 15# 12 ### # 5 22 18 16 # TANTATO # (closed) and Strike deposit 8. EP and Komis mines (closed) 14 1 20 #23 # 10 1 4# 24 # 9. Eldorado Verna, Ace-Fay, Nesbitt Labine (Eagle-Ace) 9. Corner Lake deposit 2 # 5 26 # 10. Tower East and Memorial deposits 17 # ###3 # 25 and Beaverlodge mines and Bolger open pit (closed) Lake Athabasca 21 3 2 10. Martin Lake mine (closed) 11. Birch Crossing deposits Fond du Lac # Black STONY Lake 11. Rix-Athabasca, Smitty, Leonard, Cinch and Cayzor 12. Jojay deposit RAPIDS MUDJATIK Athabasca mines (closed); St. Michael prospect 13. Star Lake mine (closed) # 27 53 12. Lorado mine (closed) 14. Jolu and Decade mines (closed) 13. Black Bay/Murmac Bay mine (closed) 15. Jasper mine (closed) Fond du Lac River 14.