An Exploratory Case Study Focusing on the Creation, Orientation and Development of a New Political Brand; the Case of the Jury Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The European Election Results 2009

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION FOR THE EASTERN REGION 4TH JUNE 2009 STATEMENT UNDER RULE 56(1)(b) OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS RULES 2004 I, David Monks, hereby give notice that at the European Parliamentary Election in the Eastern Region held on 4th June 2009 — 1. The number of votes cast for each Party and individual Candidate was — Party or Individual Candidate No. of Votes 1. Animals Count 13,201 2. British National Party – National Party – Protecting British Jobs 97,013 3. Christian Party ―Proclaiming Christ’s Lordship‖ The Christian Party – CPA 24,646 4. Conservative Party 500,331 5. English Democrats Party – English Democrats – ―Putting England First!‖ 32,211 6. Jury Team 6,354 7. Liberal Democrats 221,235 8. NO2EU:Yes to Democracy 13,939 9 Pro Democracy: Libertas.EU 9,940 10. Social Labour Party (Leader Arthur Scargill) 13,599 11. The Green Party 141,016 12. The Labour Party 167,833 13. United Kingdom First 38,185 14. United Kingdom Independence Party – UKIP 313,921 15. Independent (Peter E Rigby) 9,916 2. The number of votes rejected was: 13,164 3. The number of votes which each Party or Candidate had after the application of subsections (4) to (9) of Section 2 of the European Parliamentary Elections Act 2002, was — Stage Party or Individual Candidate Votes Allocation 1. Conservative 500331 First Seat 2. UKIP 313921 Second Seat 3. Conservative 250165 Third Seat 4. Liberal Democrat 221235 Fourth Seat 5. Labour Party 167833 Fifth Seat 6. Conservative 166777 Sixth Seat 7. UKIP 156960 Seventh Seat 4. The seven Candidates elected for the Eastern Region are — Name Address Party 1. -

County and European Elections

County and European elections Report 5 June 2009 and Analysis County and European elections Report and 5 June 2009 Analysis County and European elections 5 June 2009 3 Contents 5 Acknowledgements 7 Executive summary 9 Political context 11 Electoral systems 13 The European Parliament elections 27 The local authority elections 39 The mayoral elections 43 National implications 51 A tale of two elections 53 Appendix 53 Definition of STV European Parliament constituencies 55 Abbreviations County and European elections 5 June 2009 5 Acknowledgements The author, Lewis Baston, would like to thank his colleagues at the Electoral Reform Society for their help in compiling the data from these elections, particularly Andrew White, Hywel Nelson and Magnus Smidak in the research team, and those campaign staff who lent their assistance. Beatrice Barleon did valuable work that is reflected in the European sections. Thank you also to Ashley Dé for his efforts in bringing it to publication, and to Tom Carpenter for design work. Several Regional Returning Officers, and Adam Gray, helped with obtaining local detail on the European election results. Any errors of fact or judgement are my own. County and European elections 5 June 2009 7 Executive summary 1. In the European elections only 43.4 per cent 9. Many county councils now have lopsided supported either the Conservatives or Labour, Conservative majorities that do not reflect the the lowest such proportion ever. While this was balance of opinion in their areas. connected with the political climate over MPs’ expenses, it merely continues a long-term 10. This is bad for democracy because of the trend of decline in the two-party system. -

Scotland Date of Election Thursday 22 May 2014

European Parliamentary List of Contents and Checklist for Nomination Packs for Election Registered Parties 1. Electoral Region: Scotland Date of Election: Thursday 22 May 2014 Documents to Comments Description be returned for Election Team only 1.Information and Checklist for return of Nomination Pack 2.Letter to Prospective Registered Parties 3.Election Timetable/Main Dates 4.Candidates and Election Agents Guidance Notes 5.Deposit Refund Form 6.Nomination Paper (including List of Candidates) 7.Consent to Regional List Nomination (6 required) 8.Declaration for EU Citizens (if applicable) 9.Certificate of Authorisation (Party Candidate only – not in pack as provided by party) 9a.Request for Party Emblem (Party Candidate only) 10.Appointment/Notification of National Election Agent 11.Appointment of Election Agent for electoral region of Scotland 12.Form for appointment of sub-agents 13.Request for Register of Electors and Absent Voters and List of EROs (may be returned direct to ERO) 14.Guidelines for display of posters 15.Statutory provision for use of Schools and Rooms 16.Spending Limits 17.Information on Polling Places 18.Electoral Commission’s Code of Conduct for Campaigners 19.Previous European Election Results from 2009 20.Notice of Withdrawal 21.List of Local Returning Officers 22.Forms for appointment of Postal Voting Agents, Counting Agents and Polling Agents and Requirements of Secrecy Note: It would be helpful if you could complete the forms in BLOCK CAPITALS as appropriate. If you require any further assistance please do not hesitate to contact the Election Office’s nominations team: Graeme Donaldson 0131 529 3625 Diane Hill 0131 529 7639 Fran Cattanach 0131 469 3074 Electoral Management Board for Scotland 2. -

Scotland Region Results 2009

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS SCOTLAND REGION I, THOMAS NISBET AITCHISON, Regional Returning Officer for the Scotland Region at the European Parliamentary Elections held on 4 June 2009 do hereby give public notice, as follows, of (A) the total number of valid votes (as notified to me) given to each registered party and individual candidate and (B) the number of votes which such a party or candidate had at any stage when a seat was allocated to that party of candidate, the names in full and home address in full of each candidate who fills a seat or to whom a seat has been allocated and whether, in the case of a party, there are remaining candidates on that party’s list who have not been declared to be elected:- (A) TOTAL NUMBER OF VALID VOTES GIVEN TO EACH REGISTERED PARTY AND INDIVIDUAL CANDIDATE NAME OF REGISTERED PARTY/INDIVIDUAL CANDIDATE NUMBER OF VALID VOTES British National Party 27174 Christian Party “Proclaiming Christ’s Lordship” 16738 Conservative Party 185794 Jury Team 6257 Liberal Democrats 127038 No2EU:Yes to Democracy 9693 Scottish Green Party 80442 Scottish National Party 321007 Scottish Socialist Party 10404 Socialist Labour Party 22135 The Labour Party 229853 United Kingdom Independence Party 57788 Duncan Robertson 10189 (B) NUMBER OF VOTES REGISTERED PARTY HAD ON ALLOCATION OF SEAT(S): NAME AND HOME ADDRESS OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES; WHETHER OR NOT CANDIDATES REMAINING ON PARTY LIST NOT DECLARED ELECTED SEAT NAME OF PARTY TO NUMBER OF NAME AND ADDRESS WHETHER OR NO WHOM SEAT VOTES ON OF SUCCESSFUL NOT ALLOCATED ALLOCATION -

European Parliamentary Election Results 2009 Research Paper June

European Parliamentary Election Results 2009 Research Paper June 2009 This paper summarises the results of the European Parliamentary Elections held in Wales on 4 June 2009. Figures are provided for votes, share of the vote and turnout in Wales. Some comparisons with countries across the EU are also included. The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales and holds the Welsh Government to account. The Members’ Research Service is part of the National Assembly for Wales. We provide confidential and impartial research support to the Assembly’s scrutiny and legislation committees, and to all 60 individual Assembly Members and their staff. Members’ Research Service briefings are compiled for the benefit of Assembly Members and their support staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. We welcome comments on our briefings; please post or email to the addresses below. An electronic version of this paper can be found on the National Assembly’s website at: www.assemblywales.org/bus-assembly-publications-research.htm Further hard copies of this paper can be obtained from: Members’ Research Service National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Email: [email protected] Enquiry no: 09/2145 European Parliamentary Election Results 2009 Research Paper Rachel Dolman June 2009 Paper Number: 09/020 © National Assembly for Wales Commission 2009 © Comisiwn Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru 2009 Executive Summary This paper is intended to provide a statistical overview of the European Parliamentary election results which took place across the European Union from 4 to 7 June 2009. -

2009 European Election Results for London

2009 European election results for London Data Management and Analysis Group 2009 European election results for London DMAG Briefing 2009-07 July 2009 Gareth Piggott ISSN 1479-7879 DMAG Briefing 2009-07 1 2009 European election results for London DMAG Briefing 2009-07 July 2009 2009 European election results for London For more information please contact: Gareth Piggott Data Management and Analysis Group Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA Tel: 020 7983 4327 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © Greater London Authority, 2009 Source of all data: Regional Returning Officers All maps are © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. (Greater London Authority) (LA100032379) (2009) Data can be made available in other formats on request In some charts in this report colours that are associated with political parties are used. Printing in black and white, can make those charts hard to read. ISSN 1479-7879 This briefing is printed on at least 70 per cent recycled paper. The paper is suitable for recycling. 2 DMAG Briefing 2009-07 2009 European election results for London List of tables, charts and maps Page Turnout Map 1 Turnout 2009, by borough 5 Map 2 Change in turnout 2004-2009, by borough 5 Result Table 3 Summary of election results 1999-2009, London 5 Table 4 Order of winning seats, London 2009 6 Figure 5 Shares of votes, 2009, London and UK 7 Figure 6 Share of vote for main parties by UK region, 2009 8 London voting trends 1999-2009 Figure 7 Share of votes for main parties, UK 1999 to 2009 8 Figure 8 -

How Ireland Voted 2020 Michael Gallagher Michael Marsh • Theresa Reidy Editors How Ireland Voted 2020

How Ireland Voted 2020 Michael Gallagher Michael Marsh • Theresa Reidy Editors How Ireland Voted 2020 The End of an Era Editors Michael Gallagher Michael Marsh Department of Political Science Department of Political Science Trinity College Dublin Trinity College Dublin Dublin, Ireland Dublin, Ireland Theresa Reidy Department of Government and Politics University College Cork Cork, Ireland ISBN 978-3-030-66404-6 ISBN 978-3-030-66405-3 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66405-3 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifcally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microflms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifc statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Report on Campaign Spending at the 2009 European Parliamentary

Report on campaign spending at the 2009 European Parliamentary elections in the United Kingdom and local elections in England March 2010 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Electoral Commission: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] © The Electoral Commission 2010 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 European Parliamentary election campaign expenditure by political parties 2 Overview 4 Great Britain expenditure 5 Party expenditure (per category) 14 Northern Ireland expenditure 19 3 European Parliamentary election controlled expenditure by recognised third parties 24 4 European Parliamentary election expenditure by individual candidates 26 5 Expenditure incurred during unitary and English county elections 27 Appendices Appendix A: Parties (including Northern Ireland) that contested the European Parliamentary elections in 2004 and 2009 28 Appendix B: Expenditure categories 30 1 Introduction 1.1 The Electoral Commission’s aim is to instill integrity and public confidence in the democratic process. One of our key objectives is to ensure integrity and transparency of party and election finance. We also have a statutory duty to report on elections.1 This report provides details and analysis of the campaign expenditure incurred by political parties, third parties and candidates at the June 2009 European Parliamentary elections and also candidates at local elections in England in 2009. 1.2 This report is informed by the political parties’ campaign expenditure returns, candidates’ election expenditure returns and previous reports2 published by the Commission on the European Parliamentary elections. 1.3 The report is divided into four sections. -

European Parliamentary Election Etholiad Seneddol Ewrop Wales Region Rhanbarth Cymru Monmouth Area Sir Fynwy

European Parliamentary Election Etholiad Seneddol Ewrop Wales Region Rhanbarth Cymru Monmouth Area Sir Fynwy RESULT OF COUNT CANLYNIAD Y BLEIDLAIS Date of Election: 4th June 2009 Dyddiad Yr Etholiad: 4 Mehefin 2009 I SKF GREENSLADE being the Local Returning Officer for the European Parliamentary election in the Monmouth area on 4th June 2009 do hereby give notice that the number of votes cast for each party and individual candidate at this election was as follows: Yr wyf i, SKF GREENSLADE sef y Swyddog Canlyniadau Lleol yn Etholiad Seneddol Ewrop a Sir Fynwy gynhaliwyd ar yn hysbysu drwy hyn mai nifer y pleidleisiau a gofnodwyd dros bob Plaid neu Ymgeisydd Unigol yw fel a ganlyn: Name of Party or Individual Candidate Number of Enw’r Blaid Neu Ymgeiswyr Unigol Votes Nifer y Pleidleisiau British National Party 862 Christian Party ‘Proclaiming Christs Lordship – Plaid Gristionogol 336 Cymru ‘Datgan Arglwyddiaeth Crist’ Conservative Party – Plaid Geidwadol Cymru 8,884 Jury Team 142 Liberal Democrats – Democratiad Rhyddfrydol Cymru 2,643 No2EU: Yes to Democracy 282 Plaid Cymru – The Party of Wales 1,585 Socialist Labour Party (LEADER ARTHUR SCARGILL) 203 The Green Party – Plaid Werdd 1,833 The Labour Party – Y Blaid Lafur 3,182 United Kingdom Independence Party – Plaid Annibyniaeth Y 3,302 Derynas Unedig SAY NO TO EUROPEAN UNION The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows: Yr oedd nifer y papurau pleidleisio a wrthodwyd fel a ganlyn: Want of an official mark / absenoldeb nod syddogol 0 Voting for more candidates than voter was entitled to / Pleidleisio 64 dros ragor o ymgeiswyr nag a ganiateid I’r pleidleisiwr Writing or mark by which voter could be identified / Ysgrifeniad 2 neu nod y gellid o’I blegid adnobod y pleidleisiwr Being unmarked or wholly void for uncertainty / Heb ei farcio 35 neu’n hollol annilys oherwydd ansicrwydd Total Rejected / Cyfanswm 101 Electorate / Etholaeth: 63,028 Papers Issued / Papurau a Ddosbarthwyd : 23355 Turnout / Canran a bleidleisiodd: 37.1% Printed and Published by the Local Returning Officer. -

Election for the European Parliament Etholiad Senedd Ewrop

ELECTION FOR THE ETHOLIAD SENEDD EWROP EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RHANBARTH ETHOLIADOL CYMRU ELECTORAL REGION OF WALES Yr wyf fi, BRYN PARRY-JONES, sef y Swyddog Canlyniadau Rhanbarthol I, BRYN PARRY-JONES, being the Regional Returning Officer for Wales at dros Gymru yn Etholiad yr Aelodau i wasanaethu yn Senedd Ewrop dros the Election of Members to serve in the European Parliament for the Ranbarth Etholiadol Cymru a gynhaliwyd ar 4ydd Mehefin 2009, drwy hyn Electoral Region of Wales held on the 4th of June 2009, do hereby give yn hysbysu fod cyfanswm nifer y pleidleisiau a gofnodwyd i bob plaid notice that the total number of votes recorded for each registered party in gofrestredig yn y rhanbarth hynny fel a ganlyn:- that region is as follows:- British National Party 37,114 Christian Party “Proclaiming Christ’s Lordship” – Plaid Gristionogol 13,037 Cymru “Datgan Arglwyddiath Crist” Conservative Party – Plaid Geidwadol Cymru 145,193 Jury Team 3,793 Liberal Democrats – Democratiaid Rhyddfrydol Cymru 73,082 No2EU:Yes to Democracy 8,600 Plaid Cymru – The Party of Wales 126,702 Socialist Labour Party (LEADER ARTHUR SCARGILL) 12,402 The Green Party – Plaid Werdd 38,160 The Labour Party – Y Blaid Lafur 138,852 United Kingdom Independence Party – Plaid Annibyniaeth Y Deyrnas 87,585 Unedig SAY NO TO EUROPEAN UNION The total number of ballot papers rejected was Yr oedd cyfanswm nifer y papurau pleidleisio a wrthodwyd yn 3,128 And I do hereby declare that the undermentioned are duly Ac yr wyf fi drwy hyn yn datgan fod y rhai a enwir isod wedi eu elected -

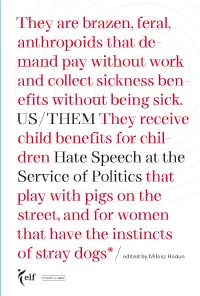

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

Front Cover with Photo – Balloon Or Elections Logo

1 EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT INFORMATION OFFICE IN THE UK MEDIA GUIDE 2014 - 2019 This guide provides journalists with information on: The European Parliament and its activities The 2009 and 2014 European elections A Who’s Who in the European Parliament Press contacts What the UK Office does Björn Kjellström Olga Dziewulska Head of UK Office Press Attachée Tel: 020 7227 4325 Tel: 020 7227 4335 Disclaimer: All information in this guide was true and correct at the time of publication. Updated information can be found on our website. www.europarl.org.uk @EPinUK 2 3 Introduction by Björn Kjellström, Head of the European Parliament Information Office in the UK Every 5 years over 500 million people in the EU have the power to choose who will represent them in the European Parliament, the world's most open and only directly elected international parliament. Our mission is to raise awareness of its role and powers, of how political differences within it are played out and of how decisions taken by its Members affect the UK. These decisions have a huge impact on everyday life and it makes a big difference who decides on our behalf. Since journalists and the media in the UK play a key role in informing citizens about how the work of the European Parliament affects them, we hope that you will find this guide useful. 4 The European Parliament Information Office in the UK Our Role: We do our best to reach as broad a spectrum of society as we can – both face to face, online and in print.