Economists' Policy Views and Voting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brazil Ahead of the 2018 Elections

BRIEFING Brazil ahead of the 2018 elections SUMMARY On 7 October 2018, about 147 million Brazilians will go to the polls to choose a new president, new governors and new members of the bicameral National Congress and state legislatures. If, as expected, none of the presidential candidates gains over 50 % of votes, a run-off between the two best-performing presidential candidates is scheduled to take place on 28 October 2018. Brazil's severe and protracted political, economic, social and public-security crisis has created a complex and polarised political climate that makes the election outcome highly unpredictable. Pollsters show that voters have lost faith in a discredited political elite and that only anti- establishment outsiders not embroiled in large-scale corruption scandals and entrenched clientelism would truly match voters' preferences. However, there is a huge gap between voters' strong demand for a radical political renewal based on new faces, and the dramatic shortage of political newcomers among the candidates. Voters' disillusionment with conventional politics and political institutions has fuelled nostalgic preferences and is likely to prompt part of the electorate to shift away from centrist candidates associated with policy continuity to candidates at the opposite sides of the party spectrum. Many less well-off voters would have welcomed a return to office of former left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010), who due to a then booming economy, could run social programmes that lifted millions out of extreme poverty and who, barred by Brazil's judiciary from running in 2018, has tried to transfer his high popularity to his much less-known replacement. -

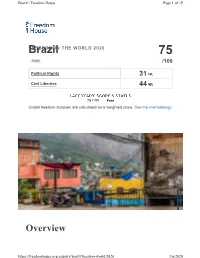

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations

Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations Updated July 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46236 SUMMARY R46236 Brazil: Background and U.S. Relations July 6, 2020 Occupying almost half of South America, Brazil is the fifth-largest and fifth-most-populous country in the world. Given its size and tremendous natural resources, Brazil has long had the Peter J. Meyer potential to become a world power and periodically has been the focal point of U.S. policy in Specialist in Latin Latin America. Brazil’s rise to prominence has been hindered, however, by uneven economic American Affairs performance and political instability. After a period of strong economic growth and increased international influence during the first decade of the 21st century, Brazil has struggled with a series of domestic crises in recent years. Since 2014, the country has experienced a deep recession, record-high homicide rate, and massive corruption scandal. Those combined crises contributed to the controversial impeachment and removal from office of President Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). They also discredited much of Brazil’s political class, paving the way for right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win the presidency in October 2018. Since taking office in January 2019, President Jair Bolsonaro has begun to implement economic and regulatory reforms favored by international investors and Brazilian businesses and has proposed hard-line security policies intended to reduce crime and violence. Rather than building a broad-based coalition to advance his agenda, however, Bolsonaro has sought to keep the electorate polarized and his political base mobilized by taking socially conservative stands on cultural issues and verbally attacking perceived enemies, such as the press, nongovernmental organizations, and other branches of government. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Outsider Politics: Radicalism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Outsider politics : Radicalism as a Political Strategy in Western Europe and Latin America A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Verónica Hoyo Committee in charge: Professor William Chandler, Chair Professor Matthew Shugart, Co-Chair Professor Akos Rona-Tas Professor Sebastian Saiegh Professor Kaare Strom 2010 Copyright Verónica Hoyo, 2010 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Verónica Hoyo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION A mis padres, Irma y Gonzalo, y a mi hermana Irma. Gracias por ser fuente constante de amor, inspiración y apoyo incondicional. Esto nunca hubiera sido posible sin ustedes. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.............................................................................................................. iii Dedication..................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents.......................................................................................................... v List of Abbreviations...................................................................................................... vi List of Tables................................................................................................................... xii List of Graphs................................................................................................................ -

The Fourth Assembly Istanbul, Turkey, April 2–5, 2006

The Fourth Assembly Istanbul, Turkey, April 2–5, 2006 Advancing Democracy: Justice, Pluralism, and Participation The World Movement for Democracy is a global network Steering Committee Members: of democrats, including activists, practitioners, academics, policy makers, and funders, who have come together to cooperate in the promotion of democracy. Mahnaz Afkhami – Iran The Washington, DC-based National Endowment for Democracy (NED) initi- ated this nongovernmental effort in February 1999 with a global Assembly in Urban Ahlin – Sweden New Delhi, India, to strengthen democracy where it is weak, to reform and invigorate democracy even where it is longstanding, and to bolster pro-democ- Genaro Arriagada– Chile racy groups in countries that have not yet entered into a process of demo- Zainab Bangura– Sierra Leone cratic transition. At the conclusion of that Inaugural Assembly, participants adopted, by consensus, a Founding Statement creating the World Movement Francesca Bomboko – Democratic for Democracy as a “pro-active network of democrats.” Emphasizing that the Republic of Congo World Movement is not a new centralized organization, the statement declares that the resulting network “will meet periodically to exchange ideas and experi- Kavi Chongkittavorn – Thailand ences and to foster collaboration among democratic forces around the world.” Ivan Doherty – Ireland Han Dongfang (Vice Chair) – China The World Movement offers new ways to give practical help to demo- crats who are struggling to open closed societies, challenge dictator- Yuri Dzhibladze -

Measuring Populism Worldwide Faculty Research Working Paper Series

Measuring Populism Worldwide Faculty Research Working Paper Series Pippa Norris Harvard Kennedy School February 2020 RWP20-002 Visit the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/research-insights/publications?f%5B0%5D=publication_types%3A121 The views expressed in the HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. Faculty Research Working Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. www.hks.harvard.edu Measuring Populism Worldwide: Norris 1/8/20 8:50 PM Measuring Populism Worldwide Pippa Norris McGuire Lecturer in Comparative Politics John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] www.pippanorris.com @PippaN15 www.GlobalPartySurvey.org Data: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/GlobalPartySurvey. Synopsis: Populism studies have rapidly burgeoned but nevertheless systematic cross-national evidence about this phenomenon has lagged far behind. How can populism be measured in ways which are consistent, valid, and reliable? To address this issue, Part I outlines the minimalist concept of populism used in the study. Part II summarizes the pros and cons of previous attempts at gauging and classifying party ideological values and issue positions in general, as well as recent studies seeking to classify populists as a distinct party family. Part III describes the research design employed to construct the Global Party Survey, replicating the methods of previous expert surveys but expanding coverage worldwide and including innovative measures of populist rhetoric. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

New Global Data on Political Parties: V-Party

BRIEFING PAPER No. #9, 26 October 2020. Anna Lührmann, Juraj Medzihorsky, INSTITUTE Garry Hindle, Staffan I. Lindberg New Global Data on Political Parties: V-Party Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) is a new dataset, produced by the V-Dem Institute, examining the policy positions and organizational structures of political parties across the world1. The largest ever study of its kind, the data highlight shifts and trends within and betweeen parties since 1970. Main Findings • This is a global trend: The median governing party in • V-Party’s Illiberalism Index shows that the Republican party in democracies has become more illiberal in recent decades. This the US has retreated from upholding democratic norms in recent means that more parties show lower commitment to political years. Its rhetoric is closer to authoritarian parties, such as AKP pluralism, demonization of political opponents, disrespect for in Turkey and Fidesz in Hungary. Conversely, the Democratic fundamental minority rights and encouragement of political party has retained a commitment to longstanding democratic violence. standards. US Parties in Comparative Perspective Figure 1 shows the movement of the Republican and Democratic The Illiberalism Index gauges the extent of commitment to parties in this millennium on two dimensions: Illiberal rhetoric and left- democratic norms that a party exhibits before an election. right positioning on economic policy. The Republican party has not changed left-right placement but moved strongly in an illiberal direc- It is the first comparative measure of the “litmus test” for the tion. In this sense it is now more similar to autocratic ruling parties such loyalty to democracy, which the famous political scientist Juan as the Turkish AKP, and Fidesz in Hungary than to typical center-right Linz developed in 1978, and Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt governing parties in democracies such as the Conservatives in the UK or CDU in Germany. -

On Coalition Government'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 24, 1945 Mao Zedong, 'On Coalition Government' Citation: “Mao Zedong, 'On Coalition Government',” April 24, 1945, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Translation from Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, Vol. 3 (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1961), 203-270. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121326 Summary: Mao Zedong defines the Chinese Communist Party's foreign policy for the post-war world, announcing that "China can never win genuine independence and equality by following the present policy of the Kuomintang government." Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation On Coalition Government April 24, 1945 I. The Fundamental Demands of the Chinese People Our congress is being held in the following circumstances. A new situation has emerged after nearly eight years of resolute, heroic and indomitable struggle waged by the Chinese people with countless sacrifices and amid untold hardships against the Japanese aggressors; in the world as a whole, decisive victory has been gained in the just and sacred war against the fascist aggressors and the moment is near when the Japanese aggressors will be defeated by the Chinese people in co-ordination with the allied countries. But China remains disunited and is still confronted with a grave crisis. In these circumstances, what ought we to do? Beyond all doubt, the urgent need is to unite representatives of all political parties and groups and of people without any party affiliation and establish a provisional democratic coalition government for the purpose of instituting democratic reforms, surmounting the present crisis, mobilizing and unifying all the anti- Japanese forces in the country to fight in effective co-ordination with the allied countries for the defeat of the Japanese aggressors, and thus enabling the Chinese people to liberate themselves from the latter's clutches. -

Hungary by Balázs Áron Kovács and Bálint Molnár

Hungary by Balázs Áron Kovács and Bálint Molnár Capital: Budapest Population: 10.0 million GNI/capita: US$18,210 Source: The data above was provided by The World Bank, World Bank Indicators 2010. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Electoral Process 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 Civil Society 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.25 1.50 1.50 1.75 1.75 Independent Media 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 Governance* 3.00 3.00 2.50 2.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.00 2.00 2.25 2.25 2.50 2.50 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a n/a n/a 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.25 2.50 2.50 Judicial Framework and Independence 2.00 2.00 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 1.75 2.00 Corruption 3.00 3.00 2.75 2.75 2.75 3.00 3.00 3.00 3.25 3.50 Democracy Score 2.13 2.13 1.96 1.96 1.96 2.00 2.14 2.14 2.29 2.39 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Carry the Revolution Through to the End

1948 Speeches/Documents Title: CARRY THE REVOLUTION THROUGH TO THE END Author: Mao Zedong Date: December 30, Source:. 1948 Description:. New Year message The Chinese people will win final victory in the great War of Liberation. Even our enemy no longer doubts the outcome. The war has followed a tortuous course. When the reactionary Kuomintang government started the counter-revolutionary war, it had approximately three and a half times as many troops as the People's Liberation Army; the equipment, manpower and material resources of its army were far superior to those of the People's Liberation Army; it had modern industries and modern means of communication, which the People's Liberation Army lacked; it had received large-scale military and economic aid from U.S. imperialism and had made long preparations. Therefore, during the first year of the war (July 1946 -- June 1947) the Kuomintang was on the offensive and the People's Liberation Army on the defensive. In 1946 in the Northeast, the Kuomintang occupied Shenyang, Szepingkai, Changchun, Kirin, Antung and other cities and most of Liaoning, Liaopei and Antung Provinces; [1] south of the Yellow River, it occupied the cities of Huaiyin and Hotse and most of the Hupeh-Honan- Anhwei, Kiangsu-Anhwei, Honan-Anhwei-Kiangsu and Southwestern Shantung Liberated Areas; and north of the Great Wall, it occupied the cities of Chengteh, Chining and Changchiakou and most of Jehol, Suiyuan and Chahar Provinces. The Kuomintang blustered and swaggered like a conquering hero. The People's Liberation Army adopted the correct strategy, which had as its main objective to wipe out the Kuomintang's effective strength rather than to hold territory, and in each month destroyed an average of some eight brigades of the Kuomintang regular troops (the equivalent of eight present-day divisions).