New Forms of Political Party Membership Political Party Innovation Primer 5 New Forms of Political Party Membership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Green Policies Are About Our Entire Way of Life”

“Green Policies Are about Our Entire Way of Life” Article by Inés Sabanés August 31, 2021 The Covid-19 pandemic is the latest in a string of crises Spain has faced in recent years, which have left the country weakened and many worried about its future. With elections on the horizon, Member of the Spanish Parliament Inés Sabanés explains how an all-encompassing Green vision can transform every aspect of society, and why Europe has the potential to help Spain overcome many of its difficulties. Green European Journal: From the perspective of the Greens (Verdes Equo), what are the key political issues facing Spain in 2021? Inés Sabanés: The pandemic has reset political priorities at both the Spanish and European levels. Three fundamental issues stick out; they were important during the 2021 Madrid elections and are present throughout our daily political life. First is the economic and social recovery: in response to the crisis caused by the pandemic but also in connection to the climate emergency. The distribution of projects arising from European funds needs to bring us out of this crisis through a fundamental structural change to the way our country works. Spain today is too susceptible to crises – our economy is overdependent on tourism for example – and needs to build its future on a more solid, productive, and better developed economic model. The second major issue is the rise of the far right. Frequent elections have been a fundamental error and a lack of consensus between parties in government has led to a rise in the number of far-right members of parliament. -

The African National Congress Centenary: a Long and Difficult Journey

The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey RAYMOND SUTTNER* The current political pre-eminence of the African National Congress in South Africa was not inevitable. The ANC was often overshadowed by other organiza- tions and there were moments in its history when it nearly collapsed. Sometimes it was ‘more of an onlooker than an active participant in events’.$ It came into being, as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC)," in $&$", at a time of realignment within both the white and the conquered black communities. In the aftermath of their victory over the Boers in the South African War ($(&&-$&#"), the British were anxious to set about reconciling their former enemies to British rule. This included allowing former Boer territories to continue denying franchise and other rights to Africans, thus disappointing the hopes raised by British under- takings to the black population during the war years. For Africans, this ‘betrayal’ signified that extension of the Cape franchise, which at that time did not discrimi- nate on racial grounds, to the rest of South Africa was unlikely. Indeed, when the Act of Union of $&$# transferred sovereignty to the white population even the Cape franchise was open to elimination through constitutional change—and in course of time it was indeed abolished. The rise of the ANC in context From the onset of white settlement of Africa in $*/", but with particular intensity in the nineteenth century, land was seized and African chiefdoms crushed one by one as they sought to retain their autonomy. The conquests helped address the demand for African labour both by white farmers and, after the discovery of diamonds and gold in $(*% and $((* respectively, by the mining industry.' * I am indebted to Christopher Saunders and Peter Limb for valuable comments, and to Albert Grundlingh and Sandra Swart for insightful discussions. -

Slovakia's Righteous Among the Nations

Slovakia’s Righteous among the Nations Gila Fatran Slovak-Jewish relations, an important factor in the rescue of Jews during the Holocaust, were influenced in no small part by events that took place in the latter third of the 19th century. That century saw the national awakening of oppressed nations. The Slovak nation, ruled by the Hungarians for 1,000 years, was struggling at the time for its national existence. The creation of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy led in 1867 to the granting of equal civil rights to the Jews in the empire in the assumption that they would assimilate nationally and culturally into the state. At the same time the Hungarian leaders stepped up their suppression of the Slovak nation. The integration of the Jews into the developing economic and cultural life and the continued improvement in their situation alongside the suppression of the aspirations of the Slovaks, were used by the political and church representatives of the Slovak nation to fan the flames of Jew-hatred and to blame the Jews for the difficult lot of the Slovak People. During this period many Slovak publications also addressed the existence of a “Jewish Question” in a negative sense: blaming the Jews for all of the Slovak society’s ills. During this era, one of the central reasons behind the rise of Slovak antisemitism was the economic factor. At the same time, the slogan “Svoj k svojmu,” which, freely translated, means “Buy only from your own people,” registered a series of “successes” in neighboring countries. However, when nationalists, using this motto, launched a campaign to persuade Slovaks to boycott Jewish-owned shops, their efforts proved unsuccessful. -

Brazil Ahead of the 2018 Elections

BRIEFING Brazil ahead of the 2018 elections SUMMARY On 7 October 2018, about 147 million Brazilians will go to the polls to choose a new president, new governors and new members of the bicameral National Congress and state legislatures. If, as expected, none of the presidential candidates gains over 50 % of votes, a run-off between the two best-performing presidential candidates is scheduled to take place on 28 October 2018. Brazil's severe and protracted political, economic, social and public-security crisis has created a complex and polarised political climate that makes the election outcome highly unpredictable. Pollsters show that voters have lost faith in a discredited political elite and that only anti- establishment outsiders not embroiled in large-scale corruption scandals and entrenched clientelism would truly match voters' preferences. However, there is a huge gap between voters' strong demand for a radical political renewal based on new faces, and the dramatic shortage of political newcomers among the candidates. Voters' disillusionment with conventional politics and political institutions has fuelled nostalgic preferences and is likely to prompt part of the electorate to shift away from centrist candidates associated with policy continuity to candidates at the opposite sides of the party spectrum. Many less well-off voters would have welcomed a return to office of former left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010), who due to a then booming economy, could run social programmes that lifted millions out of extreme poverty and who, barred by Brazil's judiciary from running in 2018, has tried to transfer his high popularity to his much less-known replacement. -

2019 European Elections the Weight of the Electorates Compared to the Electoral Weight of the Parliamentary Groups

2019 European Elections The weight of the electorates compared to the electoral weight of the parliamentary groups Guillemette Lano Raphaël Grelon With the assistance of Victor Delage and Dominique Reynié July 2019 2019 European Elections. The weight of the electorates | Fondation pour l’innovation politique I. DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN THE WEIGHT OF ELECTORATES AND THE ELECTORAL WEIGHT OF PARLIAMENTARY GROUPS The Fondation pour l’innovation politique wished to reflect on the European elections in May 2019 by assessing the weight of electorates across the European constituency independently of the electoral weight represented by the parliamentary groups comprised post-election. For example, we have reconstructed a right-wing Eurosceptic electorate by aggregating the votes in favour of right-wing national lists whose discourses are hostile to the European Union. In this case, for instance, this methodology has led us to assign those who voted for Fidesz not to the European People’s Party (EPP) group but rather to an electorate which we describe as the “populist right and extreme right” in which we also include those who voted for the Italian Lega, the French National Rally, the Austrian FPÖ and the Sweden Democrats. Likewise, Slovak SMER voters were detached from the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) Group and instead categorised as part of an electorate which we describe as the “populist left and extreme left”. A. The data collected The electoral results were collected list by list, country by country 1, from the websites of the national parliaments and governments of each of the States of the Union. We then aggregated these data at the European level, thus obtaining: – the number of individuals registered on the electoral lists on the date of the elections, or the registered voters; – the number of votes, or the voters; – the number of valid votes in favour of each of the lists, or the votes cast; – the number of invalid votes, or the blank or invalid votes. -

The Future of Europe - Perspectives Debate Was Moderated by Political Journalist Fernando from Spain Berlin

sociologist and expert from the EQUO Foundation. The The Future of Europe - Perspectives debate was moderated by political journalist Fernando from Spain Berlin. The conclusions of the seminar are presented below, after an introduction to the Spanish political system and the particularities of the economic crisis in Spain. The European Union is in The Spanish Party Political System a vulnerable situation. The project that started half a Spain is currently governed by the conservative party century ago is now (Partido Popular - PP) that holds an absolute majority staggering. (186 of 350 parliamentary seats since the 2011 elections). The landslide electoral win of the conservatives was the While its primary objective of ensuring peace on the result of a massive protest vote against the Socialist continent has been a success, subsequent Party (PSOE) for its inability to address the economic expectations of greater political integration beyond a crisis after 8 years in power. mere common market are not accomplished. The EU project itself is now in question, not only from the The Spanish party system was created with the intention outside, where the markets doubt and test the to provide on the one hand political stability to the young viability of the Euro - its economic flagship, but also democracy trough a nation-wide two-party system (the from within Europe whose citizens are beginning to electoral system making it virtually impossible for any doubt the direction of the project and the legitimacy other party except the PP and PSOE to govern) and on the of EU policies. Even in countries traditionally pro- other hand to allow the representation of regional European like Spain or Greece, where in past times political forces in the chamber of deputies, as the of dictatorship the EU was seen as the ultimate electoral system favours parties that concentrate big democratic achievement, this once unconditional amounts of votes in a specific region. -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

International Migration in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and the Outlook for East Central Europe

International Migration in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and the Outlook for East Central Europe DUŠAN DRBOHLAV* Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague Abstract: The contribution is devoted to the international migration issue in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (Czechoslovakia). Besides the contemporary trends, the international migration situation is briefly traced back to the communist era. The probable future scenario of international migration development - based especially on migration patterns that Western Europe has experienced - is also sketched, whilst mainly economic, social, political, demographic, psychological and geographical aspects are mentioned. Respecting a logical broader geopolitical and regional context, Poland and Hungary are also partly dealt with. Statistics are accompanied by some explanations, in order to see the various „faces“ of international migration (emigration versus immigration) as well as the different types of migration movements namely illegal/clandestine, legal guest-workers, political refugees and asylum seekers. Czech Sociological Review, 1994, Vol. 2 (No. 1: 89-106) 1. Introduction The aim of the first part of this contribution is to describe and explain recent as well as contemporary international migration patterns in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (and the former Czechoslovakia). The second part is devoted to sketching a possible future scenario of international migration development. In order to tackle this issue Poland and Hungary have also been taken into account. In spite of the general importance of theoretical concepts and frameworks of international migration (i.e. economic theoretical and historical-structural perspectives, psychosocial theories and systems and geographical approaches) the limited space at our disposal necessitates reference to other works that devote special attention to the problem of discussing theories1 [see e.g. -

How to Choose a Political Party

FastFACTS How to Choose a Political Party When you sign up to vote, you can join a political party. A political party is a group of people who share the same ideas about how the government should be run and what it should do. They work together to win elections. You can also choose not to join any of the political parties and still be a voter. There is no cost to join a party. How to choose a political party: • Choose a political party that has the same general views you do. For example, some political parties think that government should No Party Preference do more for people. Others feel that government should make it If you do not want to register easier for people to do things for themselves. with a political party (you • If you do not want to join a political party, mark that box on your want to be “independent” voter registration form. This is called “no party preference.” Know of any political party), mark that if you do, you may have limited choices for party candidates in “I do not want to register Presidential primary elections. with a political party” on the registration form. In • You can change your political party registration at any time. Just fill California, you can still out a new voter registration form and check a different party box. vote for any candidate in The deadline to change your party is 15 days before the election. a primary election, except If you are not registered with a political party and for Presidential candidates. -

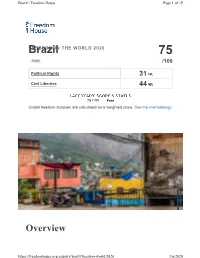

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions.