Towards Inclusive Mobility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tram Bottlenecks in Amsterdam After Implementation of the Noord-Zuidlijn

Tram bottlenecks in Amsterdam after implementation of the Noord-Zuidlijn BSc-Thesis Bobby Kartoidjojo Civil Engineering Delft University of Technology 1 Tram bottlenecks in Amsterdam after implementation of the Noord-Zuidlijn by Bobby Kartoidjojo Student number 4509846 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of science in Civil Engineering at the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) Academic year 2019-2020 Supervisors Yufei Yuan Rolf Koster Jaap Vleugel External Supervisors Niels van Oort Ties Brands Frontpage image [1] 2 Preface This Bachelor of science thesis has been carried out at the faculty of Civil Engineering at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, which is part of obtaining the BSc degree of science. This research has been done at the Department of Transport & Planning (T&P). Through a conversation with Niels van Oort, who is a researcher at TU Delft, he came up with this research topic, which is to do the after analysis. This after analysis holds that the tram network of Amsterdam after the implementation of the Noord-Zuidlijn had to be researched concerning bottlenecks. Doing the analysis was hard work, but with the help of both external supervisors, Niels van Oort and Ties Brands, I could get the job done. Also almost every week there was a meeting with the supervisors, who were critical on the work that was submitted in that specific week. That helped to improve the work that was already done. Also, the criticism of fellow students helped to improve the work. I hereby want to thank everyone that was involved in this thesis. -

A Review of the Success and Failure of Tram Systems to Carry Urban Freight: the Implications for a Low Emission Intermodal Solution Using Electric Vehicles on Trams

European Transport \ Trasporti Europei (2013) Issue 54, Paper n° 5, ISSN 1825-3997 A review of the success and failure of tram systems to carry urban freight: the implications for a low emission intermodal solution using electric vehicles on trams Niklas Arvidsson1, Michael Browne2 1University of Gothenburg, [email protected] 2University of Westminster, [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper considers the potential use of trams and Electric Distribution Vehicles (EDVs) as cargo carriers in intermodal urban freight distribution. Distribution activities are vital for society but are also the cause of environmental and social problems. Transporting goods in urban areas, where most logistics chains start or end, is an activity that increasingly generates severe problems for all stakeholders, for instance, local authorities, the logistic industry, customers and society in general. New transport solutions are necessary in order to decrease traffic congestion, noise and traffic pollution, e.g., emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants in urban areas. A possible solution to these problems is to transform the current freight distribution system within cities, for example by favouring the enhancement of intermodal transport alternatives, i.e. combining road and rail transport. Information has been collected through a literature review and interviews in Amsterdam and from these results a conceptual model is presented, as well as a low emission concept using electric vehicles on trams in Gothenburg. The concept utilizes techniques from the shipping industry, train industry, and the car industry. Keywords: light rail, tram, electric distribution vehicles, EDV, transport efficiency, sustainability, urban freight distribution, intermodal city freight distribution, urban rail freight transport 1 European Transport \ Trasporti Europei (2013) Issue 54, Paper n° 5, ISSN 1825-3997 1. -

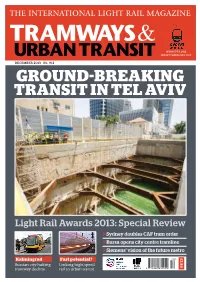

Ground-Breaking Transit in Tel Aviv

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tramnews.net DECEMBER 2013 NO. 912 GROUND-BREAKING TRANSIT IN TEL AVIV Light Rail Awards 2013: Special Review Sydney doubles CAF tram order Bursa opens city centre tramline Siemens’ vision of the future metro Kaliningrad Fast potential? £3.80 Russian city halting Linking high-speed tramway decline rail to urban transit rcp design enjoyed designing the tramways in Paris, Algiers, Le Mans, Angers... and even more the tram in Tours supplier of the year © photo léonard de serres the real life ! inspired by life www.myfrenchtram.com www.rcp.fr 2013-08-31 PUB tram and urban transit.indd 1 24/10/2013 17:22:42 500 CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association DECEMBER 2013 Vol. 76 No. 912 www.tramnews.net EDITORIAL 506 EDITOR S imon Johnston Tel: +44 (0)1733 367601 E-mail: [email protected] 13 Orton Enterprise Centre, Bakewell Road, Peterborough PE2 6XU, UK ASSOCIATE EDITOR T ony Streeter E-mail: [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR Michael Taplin Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] NEWS EDITOR John Symons 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. E-mail: [email protected] SENIOR CONTRIBUTOR 516 Neil Pulling WORLDWIDE CONTRIBUTORS Aare Olander, Nikolai Semyonov, Sergei Tarkhov (CIS), NEWS 500 SYSTEMS FACTFILE: BIELEFELD 516 Mike Russell, Norman Bartlett, Thomas Wagner, Turkey’s Bursa opens new tramline; Sydney Neil Pulling reports on a German system Pedro Costa, Richard Felski, Jordi Ibanez (Europe), doubles CAF LRV order; Tiranë tramway undergoing continual development. -

Dutch-Australian Genealogy Group

DUTCH-AUSTRALIAN GENEALOGY GROUP NEWSLETTER May 2020 Welcome to the Newsletter of the Dutch Australian Genealogy Group for May 2020 I hope your family has been able to navigate the social isolation restrictions and keep well physically and mentally during the COVID-19 crisis. It is pleasing to hear that our compliance with these restrictions has seen a decrease in the transmission of the virus and that gradually we may be able to see them relaxed. We look forward to seeing our members return to regular meetings. We are fortunate that in the year 2020 we can meet with people virtually and communicate instantly with those not in the same room. So, as the government sets restriction on our social interactions, we can still undertake many of our normal routines from home. Unfortunately, the meeting for May had to be cancelled and at this stage the August Meeting is still uncertain, but we will keep you informed. ................................................................................... FIGHTING EPIDEMICS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Every day at two o'clock we receive an update from RIVM about the latest (mortality) figures for the coronavirus. During the plague epidemics of the seventeenth century, the population was also well informed about the number of deaths. This is clearly visible in the above image of the Dam. It is a nineteenth century version of the original that was made in 1656 by Jan Lingelbach. From right to left you can see the Damrak, the now gone Waag, the Nieuwe Kerk and the new city hall under construction. Just before the town hall is a wooden house with an inscription at the top left. -

Romania's Long Road Back from Austerity

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE www.lrta.org www.tautonline.com MAY 2016 NO. 941 ROMANIA’S LONG ROAD BACK FROM AUSTERITY Systems Factfile: Trams’ dominant role in Lyon’s growth Glasgow awards driverless contract Brussels recoils from Metro attack China secures huge Chicago order ISSN 1460-8324 £4.25 Isle of Wight Medellín 05 Is LRT conversion Innovative solutions the right solution? and social betterment 9 771460 832043 AWARD SPONSORS London, 5 October 2016 ENTRIES OPEN NOW Best Customer Initiative; Best Environmental and Sustainability Initiative Employee/Team of the Year Manufacturer of the Year Most Improved System Operator of the Year Outstanding Engineering Achievement Award Project of the Year <EUR50m Project of the Year >EUR50m Significant Safety Initiative Supplier of the Year <EUR10m Supplier of the Year >EUR10m Technical Innovation of the Year (Rolling Stock) Technical Innovation of the Year (Infrastructure) Judges’ Special Award Vision of the Year For advanced booking and sponsorship details contact: Geoff Butler – t: +44 (0)1733 367610 – @ [email protected] Alison Sinclair – t: +44 (0)1733 367603 – @ [email protected] www.lightrailawards.com 169 CONTENTS The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association MAY 2016 Vol. 79 No. 941 www.tautonline.com EDITORIAL 184 EDITOR Simon Johnston Tel: +44 (0)1733 367601 E-mail: [email protected] 13 Orton Enterprise Centre, Bakewell Road, Peterborough PE2 6XU, UK ASSOCIATE EDITOR Tony Streeter E-mail: [email protected] WORLDWIDE EDITOR Michael Taplin 172 Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] NEWS EDITOR John Symons 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. -

Een Robuuste Openbaar Vervoerstructuur in Amsterdam

Een robuuste openbaar vervoerstructuur in Amsterdam Subsidiëren of investeren? Douwe Tiemersma Stadsregio Amsterdam [email protected] Bas Govers Goudappel Coffeng BV [email protected] Bijdrage aan het Colloquium Vervoersplanologisch Speurwerk 22 en 23 november 2012, Amsterdam 1 Samenvatting Onder druk van de bezuinigingsopgave is nader onderzoek verricht naar de mogelijkheden om tot een hogere efficiency te komen van het openbaar vervoer in Amsterdam. Verschillende optimaliseringsprincipes zijn onderzocht en vanuit de principes zijn samenhangende toekomstpakketten samengesteld. Een fundamentele keuze voor meerder hoofdknopen in het Amsterdamse netwerk is relevant om de veranderende vervoerstromen effectiever te bedienen. Daarnaast is een efficiencyslag in het tramnetwerk nodig om te komen tot een plusnetwerk. Afhankelijk van de hoogte van het investeringsniveau in het plusnetwerk blijken de effecten gunstig uit oogpunt van aantal reizigers, beperking van de exploitatiekosten en verbetering van de bereikbaarheid. Door een koers van investeren boven subsidiëren kan nog aanmerkelijke winst worden bereikt op weg naar een robuust openbaar vervoer in Amsterdam. 2 1. Inleiding Het kabinet Rutte heeft in haar regeeraccoord een forse extra bezuinigingsopgave op het stedelijk openbaar vervoer in de grote steden afgesproken. Ook in de Stadsregio Amsterdam dient op de exploitatie van het openbaar vervoer te worden bezuinigd, ondanks een groeiend aantal inwoners en arbeidsplaatsen in de regio. De bezuinigingsopgave vraagt om duidelijke keuzen in zowel netwerk als exploitatie van het openbaar vervoer in de regio Amsterdam. Doel is de gevolgen voor de reizigers te beperken en tegelijkertijd ruimte te scheppen voor verdere groei van het gebruik van het openbaar vervoer naar economische kerngebieden. Om deze keuzen te verkennen is de Stadsregio in 2011 een onderzoek gestart naar de mogelijkheden voor een meer efficiënte en meer effectieve exploitatie van het openbaar vervoer in de Stadsregio. -

Urban Public Transport in Europe: Technology Diffusion and Market Organisation

Transportation Research Part A 46 (2012) 269–284 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part A journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tra Urban public transport in Europe: Technology diffusion and market organisation Álvaro Costa ⇑, Ruben Fernandes CITTA – Research Centre for Territory, Transports and Environment, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Rua Dr. Roberto Frias, s/n, 4200-465 Porto, Portugal article info abstract Article history: Technological change and incremental technology, at various levels, are believed to have Received 1 July 2009 played an important role in the success of urban public transport in Europe. In this paper, Received in revised form 20 July 2011 a historical overview of the evolution of different transport modes across different Euro- Accepted 7 September 2011 pean cities is presented. Our major concern is with the processes of diffusion of urban transport modes in European cities and, in particular, with the factors, mainly of an eco- nomic nature, that may explain their rates of adoption across Europe. Among these factors, Keywords: special attention is given to the role played by the dimension and organisation of public Urban public transport transport markets in the rates of adoption of different public transport modes. The main Technological change conclusion of the paper is that the success of the introduction of a new transport mode appeared to be mainly related to its ability to provide cheaper and more reliable transport services compared with previous transport modes, and that, in the case of the electric tram, this was achieved by transforming of the structure of the market relating to this urban transport mode into monopolies. -

Inventaris Tram Amsterdam: AOM, GTA En GVBA Stichting NVBS-Railverzamelingen

Inventaris tram Amsterdam: AOM, GTA en GVBA Stichting NVBS-Railverzamelingen Auteur Dirk Eveleens Maarse beheerder collectie documentatie tramwegen Nederland en vroegere koloniën [email protected] versie 13 oktober 2018 Introductie De verzameling is ingedeeld naar onderwerp en opgeborgen in archiefdozen. Zo zijn de eerste drie dozen gewijd aan de paardentram. In elke doos bevindt zich een aantal archiefmappen, gevuld met een bepaald onderwerp, vaak onder- verdeeld in “bundels”. Ook bevat de hier gepubliceerde lijst vaak een opsomming van de belangrijkste documenten. Veel onderzoekers – vooral in het pre-internet-tijdperk – legden hun bevindingen op papier vast. Deze eigen documentatie noemen wij “huisvlijt”. Zo bevat de collectie een relatief groot aantal materieel- en routelijsten en zelf getekende kaartjes. Hoewel er intussen betrouwbare literatuur beschikbaar is en er weinig onopgeloste vragen meer overblijven, is het interessant te zien hoe eerdere generaties er in slaagden de toen vaak nog braak liggende historie te reconstrueren. Onderstaande lijst beoogt een redelijk gedetailleerd overzicht te geven van de collectie. Een complete lijst van alle aanwezige documenten is ook aanwezig, maar deze beslaat 85 geprinte pagina’s en is derhalve minder geschikt voor online publicatie. De collectie is alleen op afspraak te raadplegen. Neem hiervoor contact op met de beheerder van de verzameling Documentatie Tramwegen Nederland en geef daarbij zoveel mogelijk aan waar uw be- langstelling naar uitgaat. Voor de contactgegevens zie hierboven. -

BSRA 2014-01-11 Entertainment Report

BSRA Entertainment Report for January 11, 2014 LONG FORM (for historical record) Entertainment Report for January 11, 2014) January 11, 2014. A Spanish and Dutch Outing and a return to New England Herb Pence reported on his trips to Europe in 2012 and 2013, where he rode and photographed some interesting LRT and heritage tram line, with a few metro snapshots. We started in Madrid (Spain) in 2013, with a note that the Spanish part of the trip was cut short by a failure of Herb's film camera combined with a complete lack of availability of replacement film cameras. We saw the Madrid bus rapid transit service in marked lanes. Madrid also has a heavy rail metro, and a light rail (Metro Ligero) system that fans out into the suburbs. The Spanish government purchased 42 Alstom “Citadis 302” all-low-floor light rail vehicles (of 5 segments each) for use on light rail lines throughout the country. This is more LRVs than it can currently use, and so some have gone to systems elsewhere, while others have gone into storage pending the building of additional lines and/or the extension of existing lines (which may be some time coming due to the economic crisis in Spain). Other cities that received surplus vehicles include Adelaide (in Australia), which received 6 of them in September – November 2009 and now uses them on its Glenelg Tram line; Metro Ligero LRV numbers 165 – 170 correspond to Glenelg Tram numbers 201 – 206. We saw some of these very modern “Citadis 302” light rail vehicles, including interior photos, showing the ticket validators. -

Noord-Zuidlijn Bovengronds? Een Verkennend Onderzoek

adviseurs openbaar vervoer Noord-Zuidlijn bovengronds? een verkennend onderzoek In opdracht van SP Noord-Zuidlijn bovengronds? een verkennend onderzoek In opdracht SP van: In opdracht van: SP Datum: 5 juni 2009 Versie: definitief Opgesteld door: TransTec adviseurs BV Projectnummer: 29033 Adres: Postbus 14788, 1001 LG Amsterdam Telefoon: 020 – 669 3034 Fax: 020 – 669 3586 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.transtecadviseurs.nl Auteursrecht: © 2009 TransTec adviseurs BV Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een automatisch gegevensbestand en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van TransTec adviseurs BV. Inhoudsopgave 1 Samenvatting ...................................................................................... 2 2 Waarom dit onderzoek?....................................................................... 4 3 Noord-Zuidmetrolijn ............................................................................ 6 3.1 Waarom een Noord-Zuidmetrolijn? 6 3.2 Wat zijn de kenmerken van de Noord-Zuidmetrolijn? 6 3.3 Wanneer is de Noord-Zuidmetrolijn klaar? 7 3.4 Hoeveel Noord-Zuidmetrolijn ligt er al? 7 4 Noord-Zuidtramlijn .............................................................................. 9 4.1 Scenario’s 9 4.2 Routes 10 4.3 Infrastructuur 12 4.4 Koppeling tussen metro en tram 14 4.4.1 Algemeen 14 4.4.2 Koppeling bij de Beurs van Berlage 15 4.4.3 Koppeling bij het Europaplein 18 4.5 Capaciteit 19 4.5.1 Voertuigen 19 4.5.2 Infrastructuur 20 4.6 Voertuigen 22 4.7 Inpasbaarheid 24 4.8 Realiseringstermijn 25 4.9 Kosten versus baten 26 5 Scenario 1: Noord-Zuidtramlijn als premetro..................................... 27 5.1 Reistijd 27 5.2 Capaciteit en dienstregeling 29 5.3 Premetro versus metro 29 5.4 Toekomstopties 30 5.5 Kosten 31 6 Scenario 2: Noord-Zuidtramlijn als stadstram Noord........................ -

A Review of the Success and Failure of Tram Systems to Carry Urban Freight: the Implications for a Low Emission Intermodal Solution Using Electric Vehicles on Trams

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs European Transport \ Trasporti Europei (2013) Issue 54, Paper n° 5, ISSN 1825-3997 A review of the success and failure of tram systems to carry urban freight: the implications for a low emission intermodal solution using electric vehicles on trams Niklas Arvidsson1, Michael Browne2 1University of Gothenburg, [email protected] 2University of Westminster, [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper considers the potential use of trams and Electric Distribution Vehicles (EDVs) as cargo carriers in intermodal urban freight distribution. Distribution activities are vital for society but are also the cause of environmental and social problems. Transporting goods in urban areas, where most logistics chains start or end, is an activity that increasingly generates severe problems for all stakeholders, for instance, local authorities, the logistic industry, customers and society in general. New transport solutions are necessary in order to decrease traffic congestion, noise and traffic pollution, e.g., emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants in urban areas. A possible solution to these problems is to transform the current freight distribution system within cities, for example by favouring the enhancement of intermodal transport alternatives, i.e. combining road and rail transport. Information has been collected through a literature review and interviews in Amsterdam and from these results a conceptual model is presented, as well as a low emission concept using electric vehicles on trams in Gothenburg. The concept utilizes techniques from the shipping industry, train industry, and the car industry. -

AFC, Een Oase in Zuidas COLUMN

zORGSPECIAL voor Buitenveldert/Zuidas & Prinses Irenebuurt • een uitgave van het Huis van de Wijk Buitenveldert jaargang 32. september 2018 nr.7 AFC, een oase in Zuidas COLUMN Hans Wamsteeker De Denker en Ferry Wienneke U ligt op uw bank vlak voor de zojuist Zomer 2019 is het nieuwe sport- aangeschafte ventilator, die op orkaan- park van voetbalvereniging AFC in Zuidas gereed. Zuidas ontwik- sterkte staat. U drinkt thee: thee met en kelt zich in de komende jaren tot zonder citroen, earl grey of verveine. een gemengde wijk waarin wonen, Voor de broodnodige afwisseling neemt werken en recreëren samen komen. Het is mooi dat op de duurste vier- u een glaasje wijn. In de tuin verdorren kante meters van Nederland AFC de bladeren van de planten in de desig- een fantastisch sportpark reali- seert. Een oase in Zuidas. nbakken. Jammer, ze stonden net zo mooi op de nieuw tegels. Niet getreurd, AFC (Amsterdamsche Football Club), opgericht in 1895, zit hier al vanaf morgen andere planten kopen en flink 1961. Toen was Zuidas nog een zand- besproeien. U pakt de laptop. De minis- vlakte. De club heeft 2.200 leden en 113 teams in de competitie. Het is ter van Welzijn en Waterzorg, kortweg de grootste en oudste voetbalclub in WW, verschijnt op het scherm. Zij deelt Amsterdam. AFC speelt in de tweede divisie, het hoogste amateurniveau, mee, dat code pimpelpaars is afgekon- Toekomstig sportpark AFC in Zuidas (artist impression) semi-betaald voetbal. Het kent geen digd in verband met de nu al maanden shirtreclame maar wordt door ruim dertig bedrijven gesponsord.