SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Present Status of Fish Biodiversity and Abundance in Shiba River, Bangladesh

Univ. J. zool. Rajshahi. Univ. Vol. 35, 2016, pp. 7-15 ISSN 1023-6104 http://journals.sfu.ca/bd/index.php/UJZRU © Rajshahi University Zoological Society Present status of fish biodiversity and abundance in Shiba river, Bangladesh D.A. Khanom, T Khatun, M.A.S. Jewel*, M.D. Hossain and M.M. Rahman Department of Fisheries, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi 6205, Bangladesh Abstract: The study was conducted to investigate the abundance and present status of fish biodiversity in the Shiba river at Tanore Upazila of Rajshahi district, Bangladesh. The study was conducted from November, 2016 to February, 2017. A total of 30 species of fishes were recorded belonging to nine orders, 15 families and 26 genera. Cypriniformes and Siluriformes were the most diversified groups in terms of species. Among 30 species, nine species under the order Cypriniformes, nine species of Siluriformes, five species of Perciformes, two species of Channiformes, two species of Mastacembeliformes, one species of Beloniformes, one species of Clupeiformes, one species of Osteoglossiformes and one species of Decapoda, Crustacea were found. Machrobrachium lamarrei of the family Palaemonidae under Decapoda order was the most dominant species contributing 26.29% of the total catch. In the Shiba river only 6.65% threatened fish species were found, and among them 1.57% were endangered and 4.96% were vulnerable. The mean values of Shannon-Weaver diversity (H), Margalef’s richness (D) and Pielou’s (e) evenness were found as 1.86, 2.22 and 0.74, respectively. Relationship between Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H) and pollution indicates the river as light to moderate polluted. -

Evaluation of the Status of the Recreational Fishery for Ulua in Hawai‘I, and Recommendations for Future Management

Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources Technical Report 20-02 Evaluation of the status of the recreational fishery for ulua in Hawai‘i, and recommendations for future management October 2000 Benjamin J. Cayetano Governor DIVISION OF AQUATIC RESOURCES Department of Land and Natural Resources 1151 Punchbowl Street, Room 330 Honolulu, HI 96813 November 2000 Cover photo by Kit Hinhumpetch Evaluation of the status of the recreational fishery for ulua in Hawai‘i, and recommendations for future management DAR Technical Report 20-02 “Ka ulua kapapa o ke kai loa” The ulua fish is a strong warrior. Hawaiian proverb “Kayden, once you get da taste fo’ ulua fishing’, you no can tink of anyting else!” From Ulua: The Musical, by Lee Cataluna Rick Gaffney and Associates, Inc. 73-1062 Ahikawa Street Kailua-Kona, Hawaii 96740 Phone: (808) 325-5000 Fax: (808) 325-7023 Email: [email protected] 3 4 Contents Introduction . 1 Background . 2 The ulua in Hawaiian culture . 2 Coastal fishery history since 1900 . 5 Ulua landings . 6 The ulua sportfishery in Hawai‘i . 6 Biology . 8 White ulua . 9 Other ulua . 9 Bluefin trevally movement study . 12 Economics . 12 Management options . 14 Overview . 14 Harvest refugia . 15 Essential fish habitat approach . 27 Community based management . 28 Recommendations . 29 Appendix . .32 Bibliography . .33 5 5 6 Introduction Unique marine resources, like Hawai‘i’s ulua/papio, have cultural, scientific, ecological, aes- thetic and functional values that are not generally expressed in commercial catch statistics and/or the market place. Where their populations have not been depleted, the various ulua pop- ular in Hawai‘i’s fisheries are often quite abundant and are thought to play the role of a signifi- cant predator in the ecology of nearshore marine ecosystems. -

Marine Fish Conservation Global Evidence for the Effects of Selected Interventions

Marine Fish Conservation Global evidence for the effects of selected interventions Natasha Taylor, Leo J. Clarke, Khatija Alliji, Chris Barrett, Rosslyn McIntyre, Rebecca0 K. Smith & William J. Sutherland CONSERVATION EVIDENCE SERIES SYNOPSES Marine Fish Conservation Global evidence for the effects of selected interventions Natasha Taylor, Leo J. Clarke, Khatija Alliji, Chris Barrett, Rosslyn McIntyre, Rebecca K. Smith and William J. Sutherland Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 1 Copyright © 2021 William J. Sutherland This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Taylor, N., Clarke, L.J., Alliji, K., Barrett, C., McIntyre, R., Smith, R.K., and Sutherland, W.J. (2021) Marine Fish Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Selected Interventions. Synopses of Conservation Evidence Series. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Further details about CC BY licenses are available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Cover image: Circling fish in the waters of the Halmahera Sea (Pacific Ocean) off the Raja Ampat Islands, Indonesia, by Leslie Burkhalter. Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ -

Predator-Prey Relations at a Spawning Aggregation Site of Coral Reef Fishes

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 203: 275–288, 2000 Published September 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Predator-prey relations at a spawning aggregation site of coral reef fishes Gorka Sancho1,*, Christopher W. Petersen2, Phillip S. Lobel3 1Department of Biology, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA 2College of the Atlantic, 105 Eden St., Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, USA 3Boston University Marine Program, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA ABSTRACT: Predation is a selective force hypothesized to influence the spawning behavior of coral reef fishes. This study describes and quantifies the predatory activities of 2 piscivorous (Caranx melampygus and Aphareus furca) and 2 planktivorous (Melichthys niger and M. vidua) fishes at a coral reef fish-spawning aggregation site in Johnston Atoll (Central Pacific). To characterize preda- tor-prey relations, the spawning behavior of prey species was quantified simultaneously with mea- surements of predatory activity, current speed and substrate topography. The activity patterns of pis- civores was typical of neritic, daylight-active fish. Measured both as abundance and attack rates, predatory activity was highest during the daytime, decreased during the late afternoon, and reached a minimum at dusk. The highest diversity of spawning prey species occurred at dusk, when pisci- vores were least abundant and overall abundance of prey fishes was lowest. The abundance and predatory activity of the jack C. melampygus were positively correlated with the abundance of spawning prey, and therefore this predator was considered to have a flexible prey-dependent activ- ity pattern. By contrast, the abundance and activity of the snapper A. furca were generally not corre- lated with changes in abundance of spawning fishes. -

ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides Chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن

A study on some biological aspects of longnose trevally (Carangoides chrysophrys) in Hormozgan waters Item Type monograph Authors Kamali, Easa; Valinasab, T.; Dehghani, R.; Behzadi, S.; Darvishi, M.; Foroughfard, H. Publisher Iranian Fisheries Science Research Institute Download date 10/10/2021 04:51:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40061 وزارت ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت، آﻣﻮزش و ﺗﺮوﻳﺞﻛﺸﺎورزي ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر – ﭘﮋوﻫﺸﻜﺪه اﻛﻮﻟﻮژي ﺧﻠﻴﺞ ﻓﺎرس و درﻳﺎي ﻋﻤﺎن ﻋﻨﻮان: ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻣﺠﺮي: ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﺷﻤﺎره ﺛﺒﺖ 49023 وزارت ﺟﻬﺎد ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت، آﻣﻮزش و ﺗﺮوﻳﭻ ﻛﺸﺎورزي ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر- ﭘﮋوﻫﺸﻜﺪه اﻛﻮﻟﻮژي ﺧﻠﻴﺞ ﻓﺎرس و درﻳﺎي ﻋﻤﺎن ﻋﻨﻮان ﭘﺮوژه : ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز (Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﺷﻤﺎره ﻣﺼﻮب ﭘﺮوژه : 2-75-12-92155 ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻧﮕﺎرﻧﺪه/ ﻧﮕﺎرﻧﺪﮔﺎن : ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺠﺮي ﻣﺴﺌﻮل ( اﺧﺘﺼﺎص ﺑﻪ ﭘﺮوژه ﻫﺎ و ﻃﺮﺣﻬﺎي ﻣﻠﻲ و ﻣﺸﺘﺮك دارد ) : ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺠﺮي / ﻣﺠﺮﻳﺎن : ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻫﻤﻜﺎر(ان) : ﺳﻴﺎﻣﻚ ﺑﻬﺰادي ،ﻣﺤﻤﺪ دروﻳﺸﻲ، ﺣﺠﺖ اﷲ ﻓﺮوﻏﻲ ﻓﺮد، ﺗﻮرج وﻟﻲﻧﺴﺐ، رﺿﺎ دﻫﻘﺎﻧﻲ ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻣﺸﺎور(ان) : - ﻧﺎم و ﻧﺎم ﺧﺎﻧﻮادﮔﻲ ﻧﺎﻇﺮ(ان) : - ﻣﺤﻞ اﺟﺮا : اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ ﺷﺮوع : 92/10/1 ﻣﺪت اﺟﺮا : 1 ﺳﺎل و 6 ﻣﺎه ﻧﺎﺷﺮ : ﻣﻮﺳﺴﻪ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﺎت ﻋﻠﻮم ﺷﻴﻼﺗﻲ ﻛﺸﻮر ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ اﻧﺘﺸﺎر : ﺳﺎل 1395 ﺣﻖ ﭼﺎپ ﺑﺮاي ﻣﺆﻟﻒ ﻣﺤﻔﻮظ اﺳﺖ . ﻧﻘﻞ ﻣﻄﺎﻟﺐ ، ﺗﺼﺎوﻳﺮ ، ﺟﺪاول ، ﻣﻨﺤﻨﻲ ﻫﺎ و ﻧﻤﻮدارﻫﺎ ﺑﺎ ذﻛﺮ ﻣﺄﺧﺬ ﺑﻼﻣﺎﻧﻊ اﺳﺖ . «ﺳﻮاﺑﻖ ﻃﺮح ﻳﺎ ﭘﺮوژه و ﻣﺠﺮي ﻣﺴﺌﻮل / ﻣﺠﺮي» ﭘﺮوژه : ﺑﺮرﺳﻲ ﺑﺮﺧﻲ از وﻳﮋﮔﻲ ﻫﺎي زﻳﺴﺖ ﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ﻣﺎﻫﻲ ﮔﻴﺶ ﭘﻮزه دراز ( Carangoides chrysophrys) در آﺑﻬﺎي اﺳﺘﺎن ﻫﺮﻣﺰﮔﺎن ﻛﺪ ﻣﺼﻮب : 2-75-12-92155 ﺷﻤﺎره ﺛﺒﺖ (ﻓﺮوﺳﺖ) : 49023 ﺗﺎرﻳﺦ : 94/12/28 ﺑﺎ ﻣﺴﺌﻮﻟﻴﺖ اﺟﺮاﻳﻲ ﺟﻨﺎب آﻗﺎي ﻋﻴﺴﻲ ﻛﻤﺎﻟﻲ داراي ﻣﺪرك ﺗﺤﺼﻴﻠﻲ ﻛﺎرﺷﻨﺎﺳﻲ ارﺷﺪ در رﺷﺘﻪ ﺑﻴﻮﻟﻮژي ﻣﺎﻫﻴﺎن درﻳﺎ ﻣﻲﺑﺎﺷﺪ. -

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on Biology and Management of Marine Resources

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on biology and management of marine resources Simon Albert Ian Tibbetts, James Udy Solomon Islands Marine Life Introduction . 1 Marine life . .3 . Marine plants ................................................................................... 4 Thank you to the many people that have contributed to this book and motivated its production. It Seagrass . 5 is a collaborative effort drawing on the experience and knowledge of many individuals. This book Marine algae . .7 was completed as part of a project funded by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation Mangroves . 10 in Marovo Lagoon from 2004 to 2013 with additional support through an AusAID funded community based adaptation project led by The Nature Conservancy. Marine invertebrates ....................................................................... 13 Corals . 18 Photographs: Simon Albert, Fred Olivier, Chris Roelfsema, Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer. Bêche-de-mer . 21 com), Grant Kelly, Norm Duke, Corey Howell, Morgan Jimuru, Kate Moore, Joelle Albert, John Read, Katherine Moseby, Lisa Choquette, Simon Foale, Uepi Island Resort and Nate Henry. Crown of thorns starfish . 24 Cover art: Steven Daefoni (artist), funded by GEF/IWP Fish ............................................................................................ 26 Cover photos: Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer.com) and Fred Olivier (far right). Turtles ........................................................................................... 30 Text: Simon Albert, -

MARKET FISHES of INDONESIA Market Fishes

MARKET FISHES OF INDONESIA market fishes Market fishes indonesiaof of Indonesia 3 This bilingual, full-colour identification William T. White guide is the result of a joint collaborative 3 Peter R. Last project between Indonesia and Australia 3 Dharmadi and is an essential reference for fish 3 Ria Faizah scientists, fisheries officers, fishers, 3 Umi Chodrijah consumers and enthusiasts. 3 Budi Iskandar Prisantoso This is the first detailed guide to the bony 3 John J. Pogonoski fish species that are caught and marketed 3 Melody Puckridge in Indonesia. The bilingual layout contains information on identifying features, size, 3 Stephen J.M. Blaber distribution and habitat of 873 bony fish species recorded during intensive surveys of fish landing sites and markets. 155 market fishes indonesiaof jenis-jenis ikan indonesiadi 3 William T. White 3 Peter R. Last 3 Dharmadi 3 Ria Faizah 3 Umi Chodrijah 3 Budi Iskandar Prisantoso 3 John J. Pogonoski 3 Melody Puckridge 3 Stephen J.M. Blaber The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. ACIAR operates as part of Australia’s international development cooperation program, with a mission to achieve more productive and sustainable agricultural systems, for the benefit of developing countries and Australia. It commissions collaborative research between Australian and developing-country researchers in areas where Australia has special research competence. It also administers Australia’s contribution to the International Agricultural Research Centres. Where trade names are used, this constitutes neither endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by ACIAR. ACIAR MONOGRAPH SERIES This series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or material deemed relevant to ACIAR’s research and development objectives. -

Commercial Species List

COMMERCIAL SPECIES LIST PELAGIC DEEP-SEA (Bottomfish) cont'd Billfishes Hapuupuu, Grouper, Sea Bass, Shapon Black marlin, White Marlin, Silver Marlin, Hida Hauliuli, Snake Mackerel, Tachi Blue Marlin, Kajiki, Au B Hogo, Oopu Kae Nohu Sailfish, Au Lepe, Au S Kalekale, Kalikali Shortbill spearfish, Hebi, Au I Lehi Striped Marlin, Naragi, Au Onaga, Ula, Ulaula Koae Swordfish, Shutome, Broadbill Opakapaka Randall's Snapper Tunas Uku, Gray Snapper Aku, Skipjack, Otado, Otaru Yellow Tail Kale, Purple Paka Bigeye Tuna, Daruma, Mebachi, Ahi Poonui Bluefin Tuna JACKS/ULUA/PAPIO Dog tooth tuna, Kitsune, Soma, Watado Kawakawa, Bonito, Kawa Barred Jack, Bar Jack, Blue Trevally Keokeo, Frigate Mackeral, Oi Oi Butaguchi, Pig Lip Ulua Tombo, Albacore, Ahi Palaha Dobe, Dusky Yellowfin Tuna, Ahi Y, Koshibi, Shibiko Gunkan, Gungkan, Black Ulua Kagami, Ulua Kihikihi, Pompano, Mirror Ulua Other Pelagics Kahala, Amberjack Mahimahi, Dolphin Fish, Dorado, Equiset Kamanu, Kamano, Rainbow Runner Malolo, Flying Fish Lae, Leatherback Monchong, Pomfret, Yohando No-bite, Schleger's Jack Ono, Wahoo Omaka Opah, Moonfish, Manendai Omilu, Bluefin Trevally, Star Ulua, Nukomomi Walu, Oil fish, Hawaiian Butterfish Paopao, Yellow Ulua, Striped Ulua Papa, Island Jack SHARK Sasa, Pake Ulua, Bigeye Jack White Papio, White Ulua, Ulua Aukea, Giant Ulua Blue Shark Hammerhead Shark, Mano Kihikihi, Bay Shark INSHORE MARINE FISH Mako Shark Oceanic Whitetip Shark, Whiteitipped Reef Shark Barracudas Thresher Shark Kaku, Barracuda Tiger Shark Kawalea, Kamasu, Japanese Barracuda Mano, -

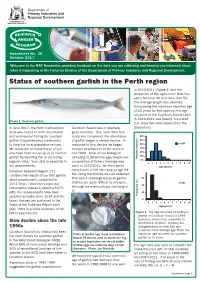

Status of Southern Garfish in the Perth Region in 2010-2011 (Figure 1) and the Proportion of Fish Aged More Than Two Years Fell from 30 % to Less Than 5%

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Newsletter No. 36 October 2017 Welcome to the RAP Newsletter, providing feedback on the data you are collecting and keeping you informed about what is happening at the Fisheries Division of the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. Status of southern garfish in the Perth region in 2010-2011 (Figure 1) and the proportion of fish aged more than two years fell from 30 % to less than 5%. The average length also declined. Considering the maximum reported age of 10 years for this species, the age structure of the Cockburn Sound stock in 2010-2011 was heavily ‘truncated’ Photo 1: Southern garfish. (i.e. older fish were absent from the In June 2017, the Perth metropolitan Cockburn Sound was in relatively population). area was closed to both recreational good condition. But, soon after this and commercial fishing for southern study was completed, the abundance 60% garfish (Hyporhamphus melanochir) of garfish began a steady decline. In 50% to help the local population recover. response to this decline we began 40% n=294 We would like to thank those of you a major assessment of the stock in 30% who have been assisting us to monitor mid-2009. Most of our biological 20% 10% garfish by donating fish or recording sampling to determine age/length/sex Percent frequency logbook data. Your data is essential to composition of fishery landings was 0% 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 our assessments. done in 2010-2011. We then spent Age (years) Fisheries Research Report 271 many hours in the lab trying to age the contains the results of our first garfish fish using the otoliths we had collected. -

Optimizing Marine Spatial Plans with Animal Tracking Data1 Robert J

497 DISCUSSION Optimizing marine spatial plans with animal tracking data1 Robert J. Lennox, Cecilia Engler-Palma, Katie Kowarski, Alexander Filous, Rebecca Whitlock, Steven J. Cooke, and Marie Auger-Méthé Abstract: Marine user–environment conflicts can have consequences for ecosystems that negatively affect humans. Strategies and tools are required to identify, predict, and mitigate the conflicts that arise between marine anthropogenic activities and wildlife. Estimating individual-, population-, and species-scale distributions of marine animals has historically been challenging, but electronic tagging and tracking technologies (i.e., biotelemetry and biologging) and analytical tools are emerging that can assist marine spatial planning (MSP) efforts by documenting animal interactions with marine infrastructure (e.g., tidal turbines, oil rigs), identifying critical habitat for animals (e.g., migratory corridors, foraging hotspots, reproductive or nursery zones), or delineating distributions for fisheries exploitation. MSP that excludes consideration of animals is suboptimal, and animal space-use estimates can contribute to efficient and responsible exploitation of marine resources that harmonize economic and ecological objectives of MSP. This review considers the application of animal tracking to MSP objectives, presents case studies of successful integration, and provides a look forward to the ways in which MSP will benefit from further integration of animal tracking data. Résumé : Les conflits entre les utilisateurs du milieu marin et l’environnement peuvent avoir des conséquences sur les écosystèmes qui, elles, ont des effets négatifs sur les humains. Des stratégies et outils sont nécessaires pour cerner, prédire et atténuer de tels conflits entre les activités humaines en mer et les espèces marines. L’estimation de la répartition d’animaux marins à l’échelle des individus, des populations et des espèces s’est avérée difficile par le passé, mais des technologies électroniques de marquage et de suivi (c.-à-d. -

2021 Louisiana Recreational Fishing Regulations

2021 LOUISIANA RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS www.wlf.louisiana.gov 1 Get a GEICO quote for your boat and, in just 15 minutes, you’ll know how much you could be saving. If you like what you hear, you can buy your policy right on the spot. Then let us do the rest while you enjoy your free time with peace of mind. geico.com/boat | 1-800-865-4846 Some discounts, coverages, payment plans, and features are not available in all states, in all GEICO companies, or in all situations. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. In the state of CA, program provided through Boat Association Insurance Services, license #0H87086. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, DC 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2020 GEICO CONTENTS 6. LICENSING 9. DEFINITIONS DON’T 11. GENERAL FISHING INFORMATION General Regulations.............................................11 Saltwater/Freshwater Line...................................12 LITTER 13. FRESHWATER FISHING SPORTSMEN ARE REMINDED TO: General Information.............................................13 • Clean out truck beds and refrain from throwing Freshwater State Creel & Size Limits....................16 cigarette butts or other trash out of the car or watercraft. 18. SALTWATER FISHING • Carry a trash bag in your car or boat. General Information.............................................18 • Securely cover trash containers to prevent Saltwater State Creel & Size Limits.......................21 animals from spreading litter. 26. OTHER RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES Call the state’s “Litterbug Hotline” to report any Recreational Shrimping........................................26 potential littering violations including dumpsites Recreational Oystering.........................................27 and littering in public. Those convicted of littering Recreational Crabbing..........................................28 Recreational Crawfishing......................................29 face hefty fines and litter abatement work. -

Garfish (Gar) 1. Fishery Summary

GARFISH (GAR) GARFISH (GAR) (Hyporhamphus ihi) Takeke 1. FISHERY SUMMARY Garfish was introduced into the QMS from 1 October 2002 with allowances, TACCs and TACs (Table 1). These have not changed. Table 1: Recreational and Customary non-commercial allowances, TACCs and TACs (t) of garfish by Fishstock. Fishstock Recreational Allowance Customary Non-Commercial Allowance TACC TAC GAR 1 20 10 25 55 GAR 2 8 4 5 17 GAR 3 2 1 5 8 GAR 4 1 1 2 4 GAR 7 10 5 8 23 GAR 8 8 4 5 17 GAR 10 0 0 0 0 1.1 Commercial fisheries Garfish landings were first recorded in 1933, and a minor fishery must have existed before this. Moderate quantities of garfish can be readily caught by experienced fishers, it is a desirable food fish, and informal sales at beaches or from wharves are likely to have been made from the late 1800s onwards. Reported landings to 1990 almost certainly understate the actual “commercial” catch. Table 2: Reported total New Zealand landings (t) of garfish from 1931 to 1990. Year Landings Year Landings Year Landings Year Landings Year Landing Year Landing 1931 − 1941 1 1951 4 1961 3 1971 11 1981 7 1932 − 1942 1 1952 7 1962 4 1972 4 1982 11 1933 1 1943 1 1953 6 1963 4 1973 10 1983 12 1934 − 1944 2 1954 8 1964 2 1974 6 1984 13 1935 − 1945 9 1955 9 1965 2 1975 2 1975 8 1936 − 1946 3 1956 7 1966 3 1976 5 1986 14 1937 − 1947 2 1957 2 1967 4 1977 5 1987 36 1938 − 1948 1 1958 2 1968 3 1978 15 1988 20 1939 4 1949 6 1959 4 1969 5 1979 12 1989 15 1940 6 1950 2 1960 6 1970 13 1980 12 1990 24 Source: Annual Reports on Fisheries (Marine Department/Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries) to 1974, and subsequent MAF data.