Maulana Daud and His Candayan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Saharanpur 82

BASE LINE SURVEY IN THE MINORITY CONCENTRATED DISTRICTS OF UTTAR PRADESH (A Report of Saharanpur District) Sponsored by: Ministry of Minority Affairs Government of India New Delhi Study conducted by: Dr. R. C. TYAGI GIRI INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES SECTOR-O, ALIGANJ HOUSING SCHEME LUCKNOW-226 024 CONTENTS Title Page No DISTRICT MAP – SAHARANPUR vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii-xii CHAPTER I: OUTLINE OF THE STUDY 1-3 1.1 About the study 1 1.2 Objective of the study 2 1.3 Methodology and Sample design 2 1.4 Tools 3 CHAPTER II: DEVELOPMENT STATUS IN SAHARANPUR DISTRICT 4-19 2.1 Introduction 4 2.2 Demographic Status 5 2.3 Demographic Status by Religion 6 2.4 Structure and Growth in Employment 7 2.5 Unemployment 8 2.6 Land Use Pattern 9 2.7 Coverage of Irrigation and Sources 10 2.8 Productivity of Major Crops 10 2.9 Livestock 11 2.10 Industrial Development 11 2.11 Development of Economic Infrastructure 12 2.12 Rural Infrastructure 13 2.13 Educational Infrastructure 14 2.14 Health Infrastructure 15 2.15 Housing Amenities in Saharanpur District 16 2.16 Sources of Drinking Water 17 2.17 Sources of Cooking Fuel 18 2.18 Income and Poverty Level 19 CHAPTER III: DEVELOPMENT STATUS AT THE VILLAGE LEVEL 20-31 3.1 Population 20 3.2 Occupational Pattern 20 3.3 Land use Pattern 21 3.4 Sources of Irrigation 21 3.5 Roads and Electricity 22 3.6 Drinking Water 22 3.7 Toilet Facility 23 3.8 Educational Facility 23 3.9 Students Enrollments 24 3.10 Physical Structure of Schools 24 3.11 Private Schools and Preferences of the People for Schools 25 3.12 Health Facility -

PREVALEI{CE and INCIDENCE of MELON MOSA.IC VIRUS OJ TWO MUS KI,IE Lon ( C U C U M I S M E Lol VARIETIE S' ARKAJE ET' AND'ark^A

J. Phytol. Res. 15 (2) : 135-236,2002 PREVALEI{CE AND INCIDENCE OF MELON MOSA.IC VIRUS_OJ TWO MUS KI,IE LoN ( C U C U M I S M E LOl VARIETIE S' ARKAJE ET' AND'ARK^A. RAJHAN' rN FATZABAD (U.P.) P.G. Department of Botany, K. S. Saket-P.G. College' Ayodhya - 224 123, Faizabad, India' Muskmelon (Cucumis melo) are grown in disease was found to be wide spread in almost all states of India. It belongs to muskmelon cropsa, and as in faizabad (U.P.) cucurbitaceous ve getable crops. Muskmelon Its incidence was as high as 80% at farmer are goodsources of Carbohydrates, Vitamin fields, keeping in view the magnitude of the A and C and minerals. So It PlaY an disease, survey was conducted to assess the important role in human nutrition. severity of this disease on muskmelon vegetable crops gmwn in the Faizabad In Faizabad district of Uttarpradesh, (U.P.) district. two muskmelon varieties'Arka Rajhan and Arkajeet' were comlnercially grown in large Survey of different Muskmelon scale with an average yield of 320q.lhact- growing farmer field area of the faizabad from'Arka Rajhan' and 156q./hact. from (U.P.) district was conducted to record the 'Arkajeet' varietiesr. However, plant incidence of melon mosaic virus in two pathogen5 have always be.en posing a varieties of Muslsrelon (Arkajeet and Arka problem in successful cultivation of these Rajhan). Ten fields were examined vegetable crops: Bhargava and Joshi2 throughout faizabad district and 25 plants reported a mosaic disease of cucurbita pepo were obseryed at random (from each field in Eastern U.P., Bhargava and Joshi3 also plot) to record the incidence and prevalence reported perpetuation of water melon of the melon mosaic virus disease. -

JEE B.Ed. 2017 – 19 Organizing University: University of Lucknow, Lucknow List of B.Ed

JEE B.Ed. 2017 – 19 Organizing University: University of Lucknow, Lucknow List of B.Ed. Colleges UName Institute Name Minority Institute type Institute Category AC SA DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, B.N.K.B. P.G. COLLEGE , AKBARPUR, AMBEDKAR NAGAR, 8004916146 NO Aided Co-Education 60 30 FAIZABAD [email protected], WWW.BNKBPG.ORG DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, K.N.I.P.S.S. MAHAVIDYALAYA , SULTANPUR, 9451232371 NO Aided Co-Education 50 40 FAIZABAD [email protected], WWW.KNMT.ORG.IN DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, K.S. SAKET P.G. COLLEGE , AYODHYA, FAIZABAD, 9415164365, NO Aided Co-Education 70 40 FAIZABAD WWW.SAKETPGCOLLEGE.AC.IN DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, KISAN P.G. COLLEGE , BAHRAICH, 9415176396 [email protected] , NO Aided Co-Education 35 25 FAIZABAD WWW.KISANPGCOLLEGE.ORG DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, L.B.S. P.G. COLLEGE , GONDA, [email protected], NO Aided Co-Education 50 30 FAIZABAD WWW.LBSPGCOLLEGE.ORG.IN DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, R.R.P.G. COLLEGE , AMETHI, 9415185070, WWW.RRPGCOLLEGE.ORG.IN NO Aided Co-Education 50 30 FAIZABAD DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, RAM NAGAR P.G. COLLEGE , RAM NAGAR, BARABANKI, 9415048236, NO Aided Co-Education 60 30 FAIZABAD [email protected], WWW.RAMNAGARPGCOLLEGE.ORG DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, A.N.D. KISAN P.G. COLLEGE , BABHNAN, GONDA, 9415038037 NO SELF FINANCE Co-Education 35 15 FAIZABAD [email protected], WWW.ANDKPGCOLLEGE.COM DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, AAKLA HASAN COLLEGE OF TEACHER TRAINING EDUCATION, SARAIPEER, BHELSAR, NO SELF FINANCE Co-Education 70 30 FAIZABAD FAIZABAD, 9936519257, [email protected] DR. RML AWADH UNIVERSITY, ABHINAV COLLEGE OF TEACHING AND TRAINING, KOLHAMPUR, NAWABGANJ, GONDA, NO SELF FINANCE Co-Education 35 15 FAIZABAD 9918000180, [email protected], WWW.ACTTG.ORG.IN DR. -

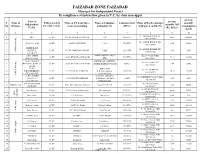

FAIZABAD ZONE FAIZABAD Manager for Independent Feeder in Compliance of Instruction Given in V.C

FAIZABAD ZONE FAIZABAD Manager for Independent Feeder In compliance of instruction given in V.C. by chairman uppcl Average Name of Average S. Name of Voltage level 11 Name of S/S from where Name of Consumer Consumer load Name of Feeder manager monthly Independent monthly bill No Division kv/ 33kv /132 kv feeder is emanating and mobile No. (KVA) with post & mobile No. Consumption Feeder (Rs. In Lac) (KVH) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Er. ASHOK KUMAR E.E. 1 MES 33 KV 132 KV DARSHAN NAGAR G.E. 3000 KVA 40.15 850000 9415901454 Er. ASHOK KUMAR E.E. 2 HOSPITAL FZD 33 KV 220 KV SOHAWAL C.M.O 379 KVA 8.05 36000 9415901454 SHREE RAM Er. ASHOK KUMAR E.E. 3 EDD Ist Faizabad HOSPITAL 33 KV 132 KV DARSHAN NAGAR C.M.S 33.10 KW 0.85 8500 9415901454 AYODHYA 33 KV AMRIT AMRIT BOTTELLERS P Er. S.P YADAV EE. 4 33 KV 132/33 KV DARSAN NAGAR 4100 KVA 71.17 931508 BOTTELLERS LTD 9415901473 33 KV 300 BED ADHICSHAK HOSPITAL Er. S.P YADAV EE. 5 HOSPITAL DARSAN 33 KV 132/33 KV DARSAN NAGAR 300 BED DARSAN NAGAR 666 KV 3.04 20542 9415901473 NAGAR 33 KV DIRECTOR Er. S.P YADAV EE. 6 N.D.UNIVERSITY 33 KV 132/33 KV KUMARGANJ N.D.UNIVERSITY 1200 KVA 24.97 271430 9415901473 KUMARGANJ KUMARGANJ EDD-II, Faizabad 11 KV 100 BED MUKHYA CHIKITSA Er. RISHIKESH YADAV SDO 7 HOSPITAL 11 KV 132/33 KV KUMARGANJ ADHIKARI 100 BED 111 KV 0.59 2651 9415901480 KUMARGANJ KUMARGANJ M/S NOOR COLD Er.S.P Singh SDO 8 EDD-Rudauli 11 KV 33/11 KV Sub-Station Sohawal Noor/9793751733 167 KVA 3.68 46054 STORAGE 9415901472 Er. -

2012* S. No. Year State Region Reason 1. 2017 Jammu And

INTERNET SHUTDOWNS IN INDIA SINCE 2012* S. Year State Region Reason No. 1. 2017 Jammu Pulwama Mobile Internet services were suspended yet again in Pulwama and district of Kashmir on 16 th August, 2017 to prevent rumour Kashmir mongering after a Lashkar commander was killed in a gunfight with the security forces. 2. 2017 Jammu Kashmir Mobile and broadband Internet services were suspended in the and Valley Kashmir valley in the morning of 15 th August, 2017 as a Kashmir precautionary measure on Independence Day. Services were reportedly restored later in the day. 3. 2017 Jammu Shopian, Internet services were suspended in Shopian and Kulgam district and Kulgam of Kashmir on 13 th August, 2017 to prevent the spreading of Kashmir information after three Hizbul Mujahideen militants including the operations commander, and two army men were killed in an encounter. 4. 2017 Jammu Pulwama Internet services were suspended in Pulwama district of Kashmir and on 9 th August, 2017 as a precautionary measure after three militants Kashmir were killed in a gunfight with the Government forces in the Tral township. However, the services on state-owned Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited remained functional. 5. 2017 Jammu Baramulla Mobile Internet services were suspended in Baramulla district of and Kashmir as a precautionary measure on 5th August, 2017 after Kashmir three LeT militants were killed in an encounter with the security forces in the Sopore town of the district. 6. 2017 Jammu Kashmir Mobile Internet services were suspended yet again across Kashmir and Valley on 1st August, 2017 as a precautionary measure fearing clashes Kashmir after the killing of Lashkar-e-Toiba commander Abu Dujana and his aide in an encounter with the security forces. -

Boctor of $F)Ilos(Op})P I Jn M I I

SUFI THOUGHT OF MUHIBBULLAH ALLAHABADI Abstract Thesis SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of $f)ilos(op})p I Jn M I I MOHD. JAVED ANS^J. t^ Under the Supervision of Prof. MUHAMMAD YASIN MAZHAR SIDDiQUi DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2006 Abstract The seventeenth Century of Christian era occupies a unique place in the history of Indian mystical thought. It saw the two metaphysical concepts Wahdat-al Wujud (Unity of Being) and Wahdat-al Shuhud (Unity of manifestation) in the realm of Muslim theosophy and his conflict expressed itself in the formation of many religious groups, Zawiyas and Sufi orders on mystical and theosophical themes, brochures, treatises, poems, letters and general casuistically literature. The supporters of these two schools of thought were drawn from different strata of society. Sheikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad, Miyan Mir, Dara Shikoh, and Sarmad belonged to the Wahdat-al Wujud school of thought; Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi, Khawaja Muhammad Masum and Gulam Yahya belonged to the other school. Shaikh Abdul Haqq Muhaddith and Shaikh WalliuUah, both of Delhi sought to steer a middle course and strove to reconcile the conflicting opinions of the two schools. Shaikh Muhibbullah of Allahabad stands head and shoulder above all the persons who wrote in favour of Wahdat-al Wujud during this period. His coherent and systematic exposition of the intricate ideas of Wahdat- al Wujud won for him the appellation of Ibn-i-Arabi Thani (the second Ibn-i Arabi). Shaikh Muhibbullah AUahabadi was a prolific writer and a Sufi of high rapture of the 17* century. -

Section-VIII : Laboratory Services

Section‐VIII Laboratory Services 8. Laboratory Services 8.1 Haemoglobin Test ‐ State level As can be seen from the graph, hemoglobin test is being carried out at almost every FRU studied However, 10 percent medical colleges do not provide the basic Hb test. Division wise‐ As the graph shows, 96 percent of the FRUs on an average are offering this service, with as many as 13 divisions having 100 percent FRUs contacted providing basic Hb test. Hemoglobin test is not available at District Women Hospital (Mau), District Women Hospital (Budaun), CHC Partawal (Maharajganj), CHC Kasia (Kushinagar), CHC Ghatampur (Kanpur Nagar) and CHC Dewa (Barabanki). 132 8.2 CBC Test ‐ State level Complete Blood Count (CBC) test is being offered at very few FRUs. While none of the sub‐divisional hospitals are having this facility, only 25 percent of the BMCs, 42 percent of the CHCs and less than half of the DWHs contacted are offering this facility. Division wise‐ As per the graph above, only 46 percent of the 206 FRUs studied across the state are offering CBC (Complete Blood Count) test service. None of the FRUs in Jhansi division is having this service. While 29 percent of the health facilities in Moradabad division are offering this service, most others are only a shade better. Mirzapur (83%) followed by Gorakhpur (73%) are having maximum FRUs with this facility. CBC test is not available at Veerangna Jhalkaribai Mahila Hosp Lucknow (Lucknow), Sub Divisional Hospital Sikandrabad, Bullandshahar, M.K.R. HOSPITAL (Kanpur Nagar), LBS Combined Hosp (Varanasi), -

Ayodhya Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1003 Canossa Convent Girls Inter College Ayodhya Buf

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 62 AYODHYA PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA BUF HIGH BUF 1001 SAHABDEENRAM SITARAM BALIKA I C AYODHYA 73 F HIGH BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 225 F 298 INTER BUF 1002 METHODIST GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 56 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 109 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUF 1003 CANOSSA CONVENT GIRLS INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 111 F SCIENCE INTER CUM 1091 DARSGAH E ISLAMI INTER COLLEGE AYODHYA 53 F ALL GROUP 329 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 627 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA AUF HIGH AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 40 F HIGH CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 11 F HIGH CRM 1140 SARDAR BHAGAT SINGH HS BARAIPARA DULLAPUR AYODHYA 20 F HIGH CRM 1208 M D M N ARYA HSS R N M G GANJ AYODHYA 7 F HIGH CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 32 F HIGH CRM 1269 S S M HSS K G ROAD GOSHAINGANJ AYODHYA 26 F HIGH CRM 1276 IMAMIA H S S AMSIN AYODHYA 15 F HIGH AUF 5004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 18 F 169 INTER AUF 1004 GOVT GIRLS I C GOSHAIGANJ AYODHYA 43 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1075 MADHURI GIRLS I C AMSIN AYODHYA 91 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRF 1125 VIDYA DEVIGIRLS I C ANKARIPUR AYODHYA 7 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1138 AMIT ALOK I C BODHIPUR AMSIN AYODHYA 96 F OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1265 A R A IC K GADAR RD GOSAINGANJ AYODHYA 74 -

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Current Condition of the Yamuna River - an Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use

Current condition of the Yamuna River - an overview of flow, pollution load and human use Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, TERI University Introduction Yamuna is the sub-basin of the Ganga river system. Out of the total catchment’s area of 861404 sq km of the Ganga basin, the Yamuna River and its catchment together contribute to a total of 345848 sq. km area which 40.14% of total Ganga River Basin (CPCB, 1980-81; CPCB, 1982-83). It is a large basin covering seven Indian states. The river water is used for both abstractive and in stream uses like irrigation, domestic water supply, industrial etc. It has been subjected to over exploitation, both in quantity and quality. Given that a large population is dependent on the river, it is of significance to preserve its water quality. The river is polluted by both point and non-point sources, where National Capital Territory (NCT) – Delhi is the major contributor, followed by Agra and Mathura. Approximately, 85% of the total pollution is from domestic source. The condition deteriorates further due to significant water abstraction which reduces the dilution capacity of the river. The stretch between Wazirabad barrage and Chambal river confluence is critically polluted and 22km of Delhi stretch is the maximum polluted amongst all. In order to restore the quality of river, the Government of India (GoI) initiated the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) in the1993and later YAPII in the year 2004 (CPCB, 2006-07). Yamuna river basin River Yamuna (Figure 1) is the largest tributary of the River Ganga. The main stream of the river Yamuna originates from the Yamunotri glacier near Bandar Punch (38o 59' N 78o 27' E) in the Mussourie range of the lower Himalayas at an elevation of about 6320 meter above mean sea level in the district Uttarkashi (Uttranchal). -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known.