Uttar Pradesh District Gazetteers: Muzaffarnagar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UTTAR PRADESH October 2007

UTTAR PRADESH October 2007 www.ibef.org STATE ECONOMY & SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE www.ibef.org STATE ECONOMY & SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE UTTAR PRADESH • October 2007 Uttar Pradesh – A Snapshot • Located in the Northern region of India, Uttar Pradesh has a population of 166 million, making it India’s most populous state (16% of India) • Occupies an area of 240, 928 sq km (9% of India) • The State covers a large part of the highly fertile and densely populated upper Gangetic plain • Shares an international border with Nepal Saharanpur and is bounded by the Indian states of UTUTTARAKHANDT A R ANC H AL Muzaffarnagar Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, Bijnor Bagpat Meerut J.P.Nagar Rampur Ghaziabad DE L H I Gautam Moradabad Bareilly Pilibhit Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Buddha Nagar BAREILY Bulandshahr NEPAL Budaun Lakhimpur H A R Y A NA Aligarh Shahjahanpur Kheri B ahraich Jharkhand and Bihar Mathura Hathras Etah Farrukhabad Sitapur Shr avasti M A T H UR A Balrampur Hardoi Maharajgunj Firozabad Siddharth Agra Mainpuri Kannauj Lucknow Gonda Nagar Khushi E tawah Unnao Barabanki Basti Gorakhpuri Nagar • The state is divided into 74 districts 300 tehsils, R A J A ST H AN KanLpuUr C K NOW S.K.Nagar A ur aiya Kanpur Faizabad Dehat Nagar Ambedkar Deoria K A NPUR Raebareli Sultanpur Nagar Jalaun Azamgarh Mau and 813 community blocks Fatehpur Ballia Pratapgarh Hamirpur Jaunpur Jhansi Kaushambi G hazipur J H ANSI Banda Mahoba A L L AH A B AD Varanasi S.R .Nagar B I H A R Chitrakoot V A R A NASI Allahabad • Administrative and Legislative -

Office of the Executive Engineer, Provinsial Division, P.W.D., Shamli

Free tenders for Civil Construction by Government Of Uttar Pradesh-5650034214 Free tenders for Civil Construction by Government Of Uttar Pradesh-4081034218 Free tenders for Civil Construction by Government Of Uttar Pradesh-4175034259 Free tenders for Civil Construction by Government Of Uttar Pradesh-1752034224 Free tenders for Civil Construction by Office Of The Executive Engineer-1546034245 Office of the Executive Engineer, Provinsial Division, P.W.D., Shamli. Tender Notice 1. The Executive Engineer, Provinsial Division, P.W.D., Prabudhnagar on behalf of Governor of Uttar Pradesh invites the sealed percentage rate bids from the eligible and approved contractors registered with UP, PWD, Class A, B, C, D & E as the case may be. 2. Detaile of works are as under Approxi Address of Bid Sl mate Time of Executive Address of Address Address of Security Cost of Address No DISTRICT Name of Work Cost Comple Engineer Superintendi of Chief District (Rs. In Bid of Bank . (Rs. In Document tion Executing ng Engineer Engineer Magistrate. Lac) Lac) the work 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 District plan in year 2012-13 new construction works S.E Office, Saharanpu C.E. Office, P. N.B, 500.00+ P.D. D.M. Kimagarh smpark marg r Circle, West Zone, Palika 38.50 3.85 300.00+ 2 P.W.D., 1 Shamli P.W.D., Office, P.W.D., Bazar, T.T. Months Shamli Saharanpu Shamli Meerut. Shamli r 500.00+ 2 2 -do- Ragunathpur smpark marg 9.00 0.90 225.00+ -do- -do- -do- -do- -do- T.T. -

Abbreviation

Abbreviation ADB - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK AERB - ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD BARC - BHABHA ATOMIC RESEARCH CENTER BDO - BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER CBRNE - CHEMICAL BIOLOGICAL RADIOLOGICAL NUCLEAR AND HIGH-YIELD EXPLOSIVE CEO - CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER CMG - CRISIS MANAGEMENT GROUP COBS - COMMUNITY BASE ORGANISATION CSO - CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS CWC - CENTRAL WATER COMMISSION DAE - DEPARTMENT OF ATOMIC ENERGY DCG - DISTRICT COMMAND GROUP DDMA - DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT DDRIC - DISTRICT DISASTER RESPONSE & INFORMATION CENTRE DM - DISASTER MANAGEMENT DP&S - DIRECTORATE OF PURCHASE AND STORES DPR - DETAILED PROJECT REPORT DRIC - DISASTER RESPONSE & INFORMATION CENTRE EOC - EMERGENCY OPERATING CENTER ERC - EMERGENCY RESPONSE CENTER ESF - EMERGENCY SUPPORT FUNCTIONS EWS - EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS FLEWS - FLOOD EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS FRERM - FLOOD AND RIVERBANK EROSION RISK MANAGEMENT GLOF - GLACIAL LAKE OUTBURST FLOODS GO - GOVERNMENT ORDER GOI - GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GSHAP - GLOBAL SEISMIC HAZARD ASSESSMENT PROGRAMME GSI - GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA HPC - HIGH POWERED COMMITTEE HRD - HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT HWB - HEAVY WATER BOARD IMD - INDIAN METROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT IPCC - INTERNATIONAL PANEL ON CLIMATE CHANGE ISR - INSTITUTE OF SEISMOLOGICAL RESEARCH ISRO - INDIAN SPACE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION LCG - LOCAL COMMAND GROUP LDOF - LANDSLIDE DAM OUTBURST FLOODS MHA - MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS MLA - MEMBER OF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY MP - MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT NCMC - NATIONAL CRISIS MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE NDMA - NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY -

Proposed UGC- Minor Research Project

Introduction Regional disparity is a ubiquitous phenomenon in both developed and developing economies. But in the latter it is more acute and glaring. When economic development occurs unequally across a country, regional differences in the levels of living become an important political issue. State economies are often composed of sets of smaller and localized economies. If the national economy is to prosper then its constituent regional economies must be brought into some sort of harmony. Any attempt to implement regional balanced -growth strategy, it is necessary to identify nature and pattern of regional development, the availability of basic amenities and the quality of infrastructure available. In Uttar Pradesh too, area disparities in the level of poverty, unemployment, income, infrastructure, agriculture, industry and above all the level of living of people exist substantially across the regions. Numerous measures have been undertaken in the last sixty years of planning to achieve balanced regional development of the State, yet wide disparities in area development continues in this state. In the regional analysis of development one comes across regions which are well developed and the peopl e in such region enjoy reasonable standard of living while in others, resource utilization and development is low owing to historical circumstances or other wise, resulting in the underdeveloped of the region whereby people have a poor 1 standard of living. The problem of imbalance in regional development thus assumes a great significance. Regional development, therefore, is interpreted as intra-regional development design to solve the problems of regions lagging behind. The first connotation of regional is e conomic in which the differences in growth, in volume and structure of production, income, and employment are taken as the measure of economic progress. -

Signature Redacted Signature of Author

A SYSTEM ANALYSIS OF CONVERTING NON-RECYCLABLE PLASTIC WASTE INTO VALUE-ADDED PRODUCTS IN A PAPER INDUSTRY CLUSTER IN INDIA ARCHIES by MASSA CJ ErS INST TUTE Padmabhushana R. Desam - LNSTLILGJY Doctor of Philosophy, Mechanical Engineering AUG 0 6 2015 University of Utah, Salt Lake City, 2006 , LIBRARIES Bachelor of Technology, Mechanical Engineering National Institute of Technology, India, 1998 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2013 2013 Padmabhushana R. Desam All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Signature of author....... ....................... .................. System Design and Management Program Signature redacted August 16, 2013 C eruued by.............. .. .. .......................... Charles H. Fine Chry er Leaders for G1o perations Pro ss of Management 1 M1'Slo nf of Management Accepted by........................S ignature red-acted - -- Patrick Hale Director System Design and Management Program 1 This page is intentionally left blank 2 A SYSTEM ANALYSIS OF CONVERTING NON-RECYCLABLE PLASTIC WASTE INTO VALUE-ADDED PRODUCTS IN A PAPER INDUSTRY CLUSTER IN INDIA by Padmabhushana R. Desam Submitted to the System Design and Management Program on August 16, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering and Management ABSTRACT Waste plastic, both industrial and municipal sources, is posing a major environmental challenges in developing countries such as India due to improper disposal methods. -

MAP:Muzaffarnagar(Uttar Pradesh)

77°10'0"E 77°20'0"E 77°30'0"E 77°40'0"E 77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E 78°10'0"E MUZAFFARNAGAR DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA (UTTAR PRADESH) 29°50'0"N KEY MAP HARIDWAR 29°50'0"N ± SAHARANPUR HARDWAR BIJNOR KARNAL SAHARANPUR CA-04 TO CA-01 CA-02 W A RDS CA-06 RO O CA-03 T RK O CA-05 W E A R PANIPAT D S N A N A 29°40'0"N Chausana Vishat Aht. U U T T OW P *# P A BAGHPAT Purquazi (NP) E MEERUT R A .! G R 29°40'0"N Jhabarpur D A W N *# R 6 M S MD Garhi Abdullakhan DR 1 Sohjani Umerpur G *# 47 D A E *#W C D Total Population within the Geographical Area as per 2011 A O A O N B 41.44 Lacs.(Approx.) R AL R A KARNAL N W A Hath Chhoya N B Barla T Jalalabad (NP) 63 A D TotalGeographicalArea(Sq.KMs) No.ChargeAreas O AW 1 S *# E O W H *#R A B .! R Kutesra A A 4077 6 Bunta Dhudhli D A Kasoli D RD N R *#M OA S A Pindaura Jahangeerpur*# *# *# K TH Hasanpur Lahari D AR N *# S Khudda O N O *# H Charge Areas Identification Tahsil Names A *# L M 5 Thana Bhawan(Rural) DR 10 9 CA-01 Kairana Un (NP) W *#.! Chhapar Tajelhera CA-02 Shamli .! Thana Bhawan (NP) Beheri *# *# CA-03 Budhana Biralsi *# Majlishpur Nojal Njali *# Basera *# *# *# CA-04 Muzaffarnagar Sikari CA-05 Khatauli Harar Fatehpur Maisani Ismailpur *# *# Roniharji Pur Charthaval (NP) *# CA-06 Jansath *# .! Charthawal Rural Garhi Pukhta (NP) Sonta Rasoolpur Kulheri 3W *# Sisona Datiyana Gadla Luhari Rampur*# *# .! 7 *# *# *# *# *# Bagowali Hind MDR 16 SH 5 Hiranwara Nagala Pithora Nirdhna *# Jhinjhana (NP) Bhainswala *# Silawar *# *# *# Sherpur Bajheri Ratheri LEGEND .! *# *# Kairi *# Malaindi Sikka Chhetela *# *# -

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 to BE ANSWERED on 10.02.2020 REGARDING PROMOTION of CNG and PNG List of Geographical Areas Covered Till 10Th CGD Bidding Round

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 1326 TO BE ANSWERED ON 10.02.2020 Promotion of CNG and PNG 1326. SHRI SANGAM LAL GUPTA: SHRI RAMDAS C. TADAS: पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री Will the Minister of PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government proposes to promote the use of CNG and PNG to control pollution; (b) if so, the cities of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra which have been connected to CNG and PNG supply so far along with the cities proposed to be connected in the near future; (c) whether the Government proposes to connect Pratapgarh in Uttar Pradesh and Wardha and Amravati in Maharashtra with CNG and PNG supply by opening CNG and PNG stations there; (d) if so, the details thereof along with the time by which it is likely to be done; and (e) if not, the reasons therefor? ANSWER पेट्रोलियम और प्राकृलिक गैस मंत्री (श्री धमेन्द्र प्रधान) MINISTER OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS (SHRI DHARMENDRA PRADHAN) (a) : Government has taken a series of decisions to promote use of CNG and PNG. (b) to (e) : Development of City Gas Distribution (CGD) networks supports the availability and accessibility of natural gas in form of Piped Natural Gas (PNG) to households, industrial uses and Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) for transportation uses. Petroleum & Natural Gas Regulatory Board (PNGRB) is the authority to grant authorization to the entities for developing of CGD network in Geographical Areas (GAs) as per PNGRB Act, 2006. PNGRB identifies GAs for authorizing the development of CGD network in synchronization with the development of natural gas pipeline connectivity and natural gas availability. -

Advance Notice to the State Or Any Government Body / Local Body

ADVANCE NOTICE TO THE STATE OR ANY GOVERNMENT BODY / LOCAL BODY The details of email addresses for sending advance notices to state or other government body/local body are as under:- ALLAHABAD a) Chief Standing Counsel, Govt. of U.P. - [email protected] All types of civil writ petitions including the (Timing for sending the notices from 10:00 A.M. matter under Article 227 of Constitution of India, to 02:00 P.M. on every working day) PIL, etc. (Only E-Court cases) [email protected] All types of Civil Appeals( Special Appeal, First (Timing for sending the notices from 10:00 A.M. Appeals, First Appeal from Order, Second to 02:00 P.M. on every working day) Appeal, Arbitration, etc.) (Only E-Court cases) [email protected] Contempt cases, Company matter, Election (Timing for sending the notices from 10:00 A.M. Petition, Testamentary and Civil revision, Trade to 02:00 P.M. on every working day) Tax Revision etc. (Only E-Court cases) b) Govt. Advocate, U.P. - [email protected] i. Criminal Misc. Writ Petiition (Timing for sending the notices from 10:00 A.M. ii. Criminal Misc. Habeas Corpus Writ Petition to 02:00 P.M. on every working day) iii. Criminal Writ – Public Interest Litigation (Only E-Court cases) iv. Criminal Writ – Matter Under Article 227 [email protected] i. Criminal Misc. Bail Application (Timing for sending the notices from 10:00 A.M. ii. Criminal Misc. Anticipatory Bail to 02:00 P.M. on every working day) Application (Only E-Court cases) [email protected] i. -

Khadi Institution Profile Khadi and Village Industries Comission

KHADI AND VILLAGE INDUSTRIES COMISSION KHADI INSTITUTION PROFILE Office Name : DO MEERUT UTTAR PRADESH Institution Code : 2160 Institution Name : KSHETRIYA SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM Address: : KAMBAL VIBHAG, SEVA SAMITI ROAD Post : MUZAFFARNAGAR City/Village : MUZAFFARNAGAR Pincode : 251001 State : UTTAR PRADESH District : MUZAFFARNAGAR Aided by : KVIC District : B Contact Person Name Email ID Mobile No. Chairman : VINOD PRAKASH 8650262927 Secretary : RAM IQBAL SINGH 9540146446 Nodal Officer : Registration Detail Registration Date Registration No. Registration Type 26-02-2016 2160 SOC Khadi Certificate No. 3197 Date : 31-MAR_2016 Khadi Mark No. Khadi Mark Dt. Sales Outlet Details Type Name Address City Pincode Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM AMBARI , DIDARGANJ 212402 DIDARGANJ KENDRA DIDARGANJ Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM JAIN STREET , KANDHALA 251001 KHADI BHANDAR KANDHALA Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN BAZAR KANDHALA 251001 KHADI BHANDAR ,KANDHALA Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM ROORKEE ROAD , PURKAJI 251317 KHADI BHANDAR PURKAJI Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN BAZAR , SHAMLI 251001 KHADI BHANDAR SHAMLI Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN BAZAR ROAD , BURANA 251001 KHADI BHANDAR BURANA Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN MUZAFFAR NAGAR 251001 KHADI BHANDAR BAZAR,KAIRANA Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN ROAD , CHARTHAWAL 251001 KHADI BHANDAR CHARTHAWAL Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM MAIN BAZAR ROAD , MEERAPUR 251001 KHADI BHANDAR MEERAPUR Sales Outlet SHRI GANDHI ASHRAM GAOSHALA ROAD MUZAFFARNAGAR 251003 KHADI BHANDAR NAI -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Agenda of 460 SEAC Meeting Dated- 04-03-2020

Agenda of 460 th SEAC Meeting Dated- 04-03-2020 Venue: Directorate of Environment, Vineet Khand-1, Gomti Nagar, Lucknow. Time: 11-00 A.M. S.L. File Online Project Details N0. N0. Proposal No. 1. 5446 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth mining at Gata No.-41808,1809,2082,2084,2089, Kairana Rural,Kairana, Shamli.,M/s 36116/2019 Rehman Brick Field,Area-4.3398 Ha) 2. 5449 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth mining at Gata No.-218, Village- Nai Nagla, Unn, District- Shamli, U.P., M/s Kisan Brick 36110/2019 Field,(Leased Area-4.3398 Ha) 3. 5455 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth mining at Gata No.-445, 446, 447, 448, 449, 450, 451, 457, Aadampur,Shamli., M/s Maha 139033/2020 Shakti Brick Field,(Area-2.089 Ha) 4. 5457 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth mining from Khasra/Gata No.-825,827,16, 878, 416, 450, 147, 158, at Vill.- 139003/2020 RudaBhavnathpur,Gopalpur,Lakshan Nagar, Makanpur, Ganeshpur,Laharpur, Sitapur.,Area-3.47Ha M/s Chand Brick Field 5. 5460 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth mining at Gata No.-674/1, 1321, 698, 711,Village- Masavi, Shamli, U.P., M/s Ekta Brick 139198/2020 Field,(Leased Area-3.489 Ha) 6. 5462 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth Mining at Gata No.-147, 148,Village-Bhaisani, Tehsil -Shamli, Shamli, U.P., M/s Jee 139206/2020 Brick Field,(Leased Area-2.462 Ha) 7. 5463 SIA/UP/MIN/ Brick Earth Mining at Gata No.-1156, 1170, 788, 1171, 226, 272, 273, 265, 418, Village- Rajwara & 134720/2020 Chandakhera Digalhai, Tehsil -Purwa, District- Unnao, U.P., M/s Jee Brick Field,(Leased Area-2.967 Ha) 8. -

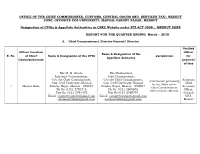

Meerut Zone, Opposite Ccs University, Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF COMMISSIONER, CUSTOMS, CENTRAL GOODS AND SERVICES TAX:: MEERUT ZONE, OPPOSITE CCS UNIVERSITY, MANGAL PANDEY NAGAR, MEERUT Designation of CPIOs & Appellate Authorities in CBEC Website under RTI ACT 2005 :: MEERUT ZONE REPORT FOR THE QUARTER ENDING March – 2018 A. Chief Commissioner/ Director General/ Director Notified Office/ Location Officer Name & Designation of the S. No. of Chief Name & Designation of the CPIO Jurisdiction for Appellate Authority Commissionerate payment of fees Shri R. K. Gupta, Shri Roshan Lal, Assistant Commissioner, Joint Commissioner O/o the Chief Commissioner, O/o the Chief Commissioner, Assistant Information pertaining Opp. CCS University, Mangal Opp. CCS University, Mangal Chief to the Office of the 1 Meerut Zone Pandey Nagar, Meerut - 250004 Pandey Nagar, Meerut - 250004 Accounts Chief Commissioner, Ph No: 0121-2792745 Ph No: 0121-2600605 Officer, Meerut Zone, Meerut. Fax No: 0121-2761472 Fax No:0121-2769707 Central Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] GST, [email protected] [email protected] Meerut B. Commissioner/ Addl. Director General Notified S. Commission Name & Designation of the officer for Name & Designation of the CPIO Jurisdiction No. erate Appellate Authority payment of fees Areas falling Shri Kamlesh Singh Shri Roshan Lal Joint Commissioner under the Assistant Chief Assistant Commissioner Districts of Accounts O/o the Commissioner, Office of the Commissioner of Central Meerut, Officer, Office Central GST Commissionerate Goods & Services Tax, Baghpat, of the Central GST Meerut, Opp. CCS University, Commissionerate: Meerut, Opposite: Muzaffarnagar, Commissioner Meerut Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut. Saharanpur, 1 Chaudhary Charan Singh University, of Central Commissione Fax No: 0121-2792773 Shamli, Goods & Mangal Pandey Nagar, Meerut- rate Amroha, Services Tax, 250004 Moradabad, Commissionera Bijnore and te: Meerut Ph No: 0121-2600605 Rampur in the Fax No:0121-2769707 State of Uttar Pradesh.