Jonathan Belcher: Colonial Governor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

Windsor's Importance in Vermont's History Prior to the Establishment of the Vermont Constitution

PROCEEDINGS OF THE VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEARS 1921, 1922 AND 1923 CAPI TAL C ITY PRESS MONTPE LIER, VT. 192 4 Windsor's Importance in Vermont's History Prior to the Establishment of the Vermont Constitution A PAPER READ BEFORE THE VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY AT WINDSOR IN THE OLD CONSTITUTION HOUSE SEPTEMBER 4, 1822 By Henry Steele Wardner Windsor's Importance in Vermont's History To be invited to address you in this, my native town and still my home, and in this, the most notable of Vermont's historic buildings, gives me real pleasure. That pleasure is the greater because of my belief that through the neglect of some of Vermont's historians as well as through the enter prise of others who, like myself, have had their own towns or group of individuals to serve and honor, the place of Windsor in Vermont's written history is not what the town deserves and because your invitation gives me an opportunity to show some forgotten parts of Windsor's claim to historic impor tance. Today I shall not describe the three celebrated conven tions held in this town in 1777, the first of which gave to the State its name, while the second and third created the State and gave to it its corporate existence and its first constitution; nor shall I touch upon the first session of Vermont's legislature held here in 1778, although upon these several events mainly hangs Windsor's fame as far as printed history is concerned. Nor shall I dwell upon Windsor as the first town of Vermont in culture and social life through the last decade of the eigh teenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth, nor yet upon the extraordinary influence which the early artisans and inventors of this town have had upon industries in various parts of the world. -

PERSONAL INVENTORY IF You Were Not Satisfied with Your Choir Last Season: If the Attendance Was Not What You Had Hoped For;

PERSONAL INVENTORY IF you were not satisfied with your choir last season: If the attendance was not what you had hoped for; and disci- pline left something to be desired; if the children's response was half-hearted:--then check your stock of the following items: I. ENTHUSIASM. Can you get excited about your work? Or is it an endurance contest? If you find it dull and depressing, you can be sure it is the same for the children. How you feel about your work is as important as how much you know about it. And how you feel about it is sure to be re- flected in the children. You have a job that is worth getting enthusiastic about. Enjoy the fine experiences it brings you, and learn to forget the little irritations. What happens in rehearsal may influence a whole life. 2. CAN YOU OVERLOOK? Benjamin Franklin once said, "There is a time to wink, and a time to see." Learn to distinguish be- tween natural ordinary wiggling, and intentional disturbance. 3.INTERESTING. Discipline, anyhow, is a sign of failure. If you could make the work interesting enough, there would be little trouble. More work and less worry: Learning music can be either exciting or dull. What it is to you, it will surely be to the children, too. 4.HUMOR. If you can't see a joke, work on yourself until you can. If something funny happens in rehearsal, enjoy the situation and let everybody else enjoy it, too. It's much better for everybody to laugh together, than for some to be laughing at others. -

A History of Chichester

A History of Chichester . Written on the occasion of our 250th Anniversary 1727 -1977 CONTENTS Preface. .. 5 The Establishment of Chichester. .. 7 Original Gran t . .. 8 Early Beginnings. .. 10 The Settlement of Chichester. .. 22 The Churches. .. 58 The Schools. .. 67 Old Home Day Celebrations. .. 80 Organizations. .. 87 Town Services. 102 Town Cemeteries. 115 Wars and Veterans. .. 118 3 PREFACE Our committee was formed to put into print some account of our town's history to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the granting of the original charter of our town. The committee has met over the past year and one-half and a large part of the data was obtained from the abstracts of the town records which were kept by Augustus Leavitt, Harry S. Kelley's history notes written in 1927 for the 200th anniversary and from the only sizable printed history of Chichester written by D. T. Brown in Hurd's History of Merrimack and Belknap Counties containing thirty seven pages. In researching we found that a whole generation is missing. It is regrettable that a history wasn't done before now when much that is now lost was within the mem- ory of some living who had the knowledge of our early history. Our thanks to the townspeople who have contributed either information, pic- tures, maps and written reports. It is our hope that the contents will be interesting and helpful to this and future generations. The Chichester History Committee Rev. H. Franklin Parker June E. Hatch Ruth E. Hammen 5 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF CHICHESTER Chichester was one of seven towns granted in New Hampshire in 1727 while Lieutenant Governor John Wentworth administered the affairs of the province, then a part of Massachusetts. -

The Architects of Eighteenth Century English Freemasonry, 1720 – 1740

The Architects of Eighteenth Century English Freemasonry, 1720 – 1740 Submitted by Richard Andrew Berman to the University of Exeter as a Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Research in History 15 December 2010. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis that is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. R A Berman 1 | P a g e Abstract Following the appointment of its first aristocratic Grand Masters in the 1720s and in the wake of its connections to the scientific Enlightenment, ‘Free and Accepted’ Masonry rapidly became part of Britain’s national profile and the largest and arguably the most influential of Britain’s extensive clubs and societies. The new organisation did not evolve naturally from the mediaeval guilds and religious orders that pre-dated it, but was reconfigured radically by a largely self-appointed inner core. Freemasonry became a vehicle for the expression and transmission of the political and religious views of those at its centre, and for the scientific Enlightenment concepts that they championed. The ‘Craft’ also offered a channel through which many sought to realise personal aspirations: social, intellectual and financial. Through an examination of relevant primary and secondary documentary evidence, this thesis seeks to contribute to a broader understanding of contemporary English political and social culture, and to explore the manner in which Freemasonry became a mechanism that promoted the interests of the Hanoverian establishment and connected and bound a number of élite metropolitan and provincial figures. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820

128 American Antiquarian Society. [April, BIBLIOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS, 1690-1820 PART III ' MARYLAND TO MASSACHUSETTS (BOSTON) COMPILED BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM The following bibliography attempts, first, to present a historical sketch of every newspaper printed in the United States from 1690 to 1820; secondly, to locate all files found in the various libraries of the country; and thirdly, to give a complete check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society. The historical sketch of each paper gives the title, the date of establishment, the name of the editor or publisher, the fre- quency of issue and the date of discontinuance. It also attempts to give the exact date of issue when a change in title or name of publisher or frequency of publication occurs. In locating the files to be found in various libraries, no at- tempt is made to list every issue. In the case of common news- papers which are to be found in many libraries, only the longer files are noted, with a description of their completeness. Rare newspapers, which are known by only a few scattered issues, are minutely listed. The check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society follows the style of the Library of Con- gress "Check List of Eighteenth Century Newspapers," and records all supplements, missing issues and mutilations. The arrangement is alphabetical by states and towns. Towns are placed according to their present State location. For convenience of alphabetization, the initial "The" in the titles of papers is disregarded. Papers are considered to be of folio size, unless otherwise stated. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

The Long-Ago Squadrons of Cambridge

The Long-ago Squadrons of Cambridge Michael Kenney Cambridge Historical Commission January 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project was triggered by noting a curious description of early land divisions in Cambridge — “squadrons” — while reading an early draft of Building Old Cambridge. Co-author Charles M. Sullivan suggested that I investigate the use of that term in colonial Massachusetts. The results of that investigation are presented in this paper. Thanks are due to Sullivan, and also to his British colleague Roger Thompson. Others who aided my research with their comments included Christopher J. Lenney and Brian Donahue whose contributions are noted in the text. The reconstructed map appears in Building Old Cambridge. Sara Kenney gave a careful reading and many helpful suggestions. “Squadrons” is a curious term that shows up in the early records of Cambridge and a number of other towns in Middlesex County and eastern Worcester County. Its curiousness comes from the fact that not only is it a term that had disappeared from use by the late 1700s and apparently appears nowhere else, but also that its origin is obscure. In Cambridge it was used in 1683, 1707 and 1724 to describe divisions of land. Recent research in other town histories finds that “squadron” was used either for that purpose or to describe what soon became known as school districts. In only three of the towns studied so far did it have the military significance which it has today, and which it had in England as early as 1562. Left unanswered is the question of why this term appeared in New England by 1636 (in Watertown) and had disappeared by 1794 (in Chelmsford) — and why it was apparently used only in Middlesex County and nearby Worcester County, as well as one very early use in New Haven, Connecticut. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

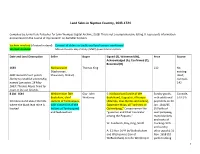

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665].