The Genus Olea: Molecular Approaches of Its Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vascular Plant Survey of Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve, Malawi

YIKA-VWAZA TRUST RESEARCH STUDY REPORT N (2017/18) Vascular Plant Survey of Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve, Malawi By Sopani Sichinga ([email protected]) September , 2019 ABSTRACT In 2018 – 19, a survey on vascular plants was conducted in Vwaza Marsh Wildlife Reserve. The reserve is located in the north-western Malawi, covering an area of about 986 km2. Based on this survey, a total of 461 species from 76 families were recorded (i.e. 454 Angiosperms and 7 Pteridophyta). Of the total species recorded, 19 are exotics (of which 4 are reported to be invasive) while 1 species is considered threatened. The most dominant families were Fabaceae (80 species representing 17. 4%), Poaceae (53 species representing 11.5%), Rubiaceae (27 species representing 5.9 %), and Euphorbiaceae (24 species representing 5.2%). The annotated checklist includes scientific names, habit, habitat types and IUCN Red List status and is presented in section 5. i ACKNOLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, let me thank the Nyika–Vwaza Trust (UK) for funding this work. Without their financial support, this work would have not been materialized. The Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) Malawi through its Regional Office (N) is also thanked for the logistical support and accommodation throughout the entire study. Special thanks are due to my supervisor - Mr. George Zwide Nxumayo for his invaluable guidance. Mr. Thom McShane should also be thanked in a special way for sharing me some information, and sending me some documents about Vwaza which have contributed a lot to the success of this work. I extend my sincere thanks to the Vwaza Research Unit team for their assistance, especially during the field work. -

Djvu Document

BULL BQT. ~URV.INDIA Vol. 10, NOS.3 & 4 : pp. 397-400, 1968 TAXONOMIC POSITION OF THE GENUS NYCTANTHES B. C. Kmu AND ANIMADE Bosc Znstifulc, Calcutta ABSTRACT The genus Nyctanthes with only one species N. arbor-tristis Linn. having flowers like that of JaJrninm was originally induded in Oleaceae. In view of its strongly quadrangular stem and its apparent resemblance to Tectona and other members of the family Verbenaceae, Airy Shaw (1952) placed the genus in a new subfamily under the family Verbenaceae. Stant (K952) gave some anatomical evidence for the inclusion of Nyctanthes in the Verbenaceae. On the basis of com- parative study of Nyctanthas, along with some members of Oleaceae, Verbenaceae and Loganiaceae on cytology, general anatomy of stem and leaf, wood anatomy, floral anatomy and palynology and also on the preliminary data of the chemical constituents present in the plants, the authors state that Nyctanfhes has not much affinityto the members of the Verbenaceae, although it has some similarity with several oleaceous members, After taking all points into consideration this genus is assigned to a new family Nyctanthaceae. INTRODUCTION thes is consistent with its being incluiled in the The Genus Nyctanthes Linn. with only .one Verbenaceae. On the basis of anatomical and species N. arbor-tristis Linn. was originally included palynological studies on Nyctanthes arbor-tristis, in the family Oleaceae mainly on account of the Kundu (1966) was of opinion that Nyctamthes structure of the flower which is somewhat like that belongs neither to the Oleaceae nor to the .Verben- of Jasminum. A second species N. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Olea Europaea L. a Botanical Contribution to Culture

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 2 (4): 382-387, 2007 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2007 Olea europaea L. A Botanical Contribution to Culture Sophia Rhizopoulou National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Biology, Section of Botany, Panepistimioupoli, Athens 157 84, Greece Abstract: One of the oldest known cultivated plant species is Olea europaea L., the olive tree. The wild olive tree is an evergreen, long-lived species, wide-spread as a native plant in the Mediterranean province. This sacred tree of the goddess Athena is intimately linked with the civilizations which developed around the shores of the Mediterranean and makes a starting point for mythological and symbolic forms, as well as for tradition, cultivation, diet, health and culture. In modern times, the olive has spread widely over the world. Key words: Olea • etymology • origin • cultivation • culture INTRODUCTION Table 1: Classification of Olea ewopaea Superdivi&on Speimatophyta-seed plants Olea europaea L. (Fig. 1 & Table 1) belongs to a Division Magnohophyta-flowenng plants genus of about 20-25 species in the family Oleaceae [1-3] Class Magn olio psi da- dicotyledons and it is one of the earliest cultivated plants. The olive Subclass Astendae- tree is an evergreen, slow-growing species, tolerant to Order Scrophulanale- drought stress and extremely long-lived, with a life Family Oleaceae- olive family expectancy of about 500 years. It is indicative that Genus Olea- olive Species Olea europaea L. -olive Theophrastus, 24 centuries ago, wrote: 'Perhaps we may say that the longest-lived tree is that which in all ways, is able to persist, as does the olive by its trunk, by its power of developing sidegrowth and by the fact its roots are so hard to destroy' [4, book IV. -

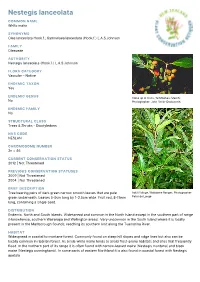

Nestegis Lanceolata

Nestegis lanceolata COMMON NAME White maire SYNONYMS Olea lanceolata Hook.f.; Gymnelaea lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FAMILY Oleaceae AUTHORITY Nestegis lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Close up of fruits, Te Moehau (March). No Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE NESLAN CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 46 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Tree bearing pairs of dark green narrow smooth leaves that are pale Adult foliage, Waitakere Ranges. Photographer: green underneath. Leaves 5-9cm long by 1-2.5cm wide. Fruit red, 8-11mm Peter de Lange long, containing a single seed. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. North and South Islands. Widespread and common in the North Island except in the southern part of range (Horowhenua, southern Wairarapa and Wellington areas). Very uncommon in the South Island where it is locally present in the Marlborough Sounds, reaching its southern limit along the Tuamarina River. HABITAT Widespread in coastal to montane forest. Commonly found on steep hill slopes and ridge lines but also can be locally common in riparian forest. As a rule white maire tends to avoid frost-prone habitats and sites that frequently flood. In the northern part of its range it is often found with narrow-leaved maire (Nestegis montana) and black maire (Nestegis cunninghamii). In some parts of eastern Northland it is also found in coastal forest with Nestegis apetala. FEATURES Stout gynodioecious spreading tree up to 20 m tall usually forming a domed canopy; trunk up to c. -

Chionanthus (Oleaceae) (Stapf) Kiew, Comb. Sagu, Padang Unique Among Being Ridged. Its Strongly Flattened Twigs, Long Petioles

BLUMEA 43 (1998) 471-477 Name changes for Malesian species of Chionanthus (Oleaceae) Ruth Kiew Singapore Botanic Gardens, Cluny Road, Singapore 259569 Summary New combinations under Chionanthus L. are made for Linociera beccarii, L. brassii, L. clementis, L. gigas, L. hahlii, L. kajewskii, L. nitida, L. remotinervia, L. riparia, L. rupicola, L. salicifolia, L. and L. Linociera is with C. L. sessiliflora stenura. cumingiana synonymous ramiflorus, novo- guineensis and L. ovalis with C. rupicolus, L. papuasica with C. sessiliflorus and L. pubipanicu- be lata with C. mala-elengi subsp. terniflorus. Linociera macrophylla sensu Whitmore proves to C. hahlii. Key words '. Malesia, Chionanthus,Oleaceae. Introduction The reduction of Linociera Sw. to Chionanthus L. (Steam, 1976) necessitates name changes to be made for species described inLinociera. In addition, as the family has been studied on a geographical rather than country basis, several species prove to be In for Vidal and two synonyms. some cases, notably a type Ledermanntypes, neotypes have had to be chosen because the holotype is no longer extant and isotypes have not been located. 1. Chionanthus beccarii (Stapf) Kiew, comb. nov. Linociera beccarii Stapf, Kew Bull. (1915) 115. —Type: Beccari PS 826 (holoK; isoL), Sumatra, Padang, Ayer Mancior. Distribution — Malesia: Sumatra (G. Leuser, G. Sagu, Padang and Asahan). — rather it is from Note Apparently a rare tree, known only the northern half of Sumatrawhere it grows in mountainforest between 360 and 1200 m. Its large fruit is unique among Malesian Chionanthus in being flattened laterally as well as being ridged. Its strongly flattened twigs, long petioles, narrowly obovate leaves with an acute apex, and rotund foliaceous bracts combine to make it a distinctive species. -

Towards Resolving Lamiales Relationships

Schäferhoff et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:352 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/352 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Towards resolving Lamiales relationships: insights from rapidly evolving chloroplast sequences Bastian Schäferhoff1*, Andreas Fleischmann2, Eberhard Fischer3, Dirk C Albach4, Thomas Borsch5, Günther Heubl2, Kai F Müller1 Abstract Background: In the large angiosperm order Lamiales, a diverse array of highly specialized life strategies such as carnivory, parasitism, epiphytism, and desiccation tolerance occur, and some lineages possess drastically accelerated DNA substitutional rates or miniaturized genomes. However, understanding the evolution of these phenomena in the order, and clarifying borders of and relationships among lamialean families, has been hindered by largely unresolved trees in the past. Results: Our analysis of the rapidly evolving trnK/matK, trnL-F and rps16 chloroplast regions enabled us to infer more precise phylogenetic hypotheses for the Lamiales. Relationships among the nine first-branching families in the Lamiales tree are now resolved with very strong support. Subsequent to Plocospermataceae, a clade consisting of Carlemanniaceae plus Oleaceae branches, followed by Tetrachondraceae and a newly inferred clade composed of Gesneriaceae plus Calceolariaceae, which is also supported by morphological characters. Plantaginaceae (incl. Gratioleae) and Scrophulariaceae are well separated in the backbone grade; Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae appear in distant clades, while the recently described Linderniaceae are confirmed to be monophyletic and in an isolated position. Conclusions: Confidence about deep nodes of the Lamiales tree is an important step towards understanding the evolutionary diversification of a major clade of flowering plants. The degree of resolution obtained here now provides a first opportunity to discuss the evolution of morphological and biochemical traits in Lamiales. -

Torus-Bearing Pit Membranes in Species of Osmanthus

IAWA Journal, Vol. 31 (2), 2010: 217–226 TORUS-BEARING PIT MEMBRANES IN SPECIES OF OSMANTHUS Roland Dute1, 5, David Rabaey2, John Allison1 and Steven Jansen3, 4 SUMMARY Torus thickenings of pit membranes are found not only in gymnosperms, but also in certain genera of dicotyledons. One such genus is Osmanthus. Wood from 17 species of Osmanthus was searched for tori. Fourteen spe- cies from three of the four sections investigated possessed these thick- enings. Ten of the species represent new records. Only the three New Caledonian species of Section Notosmanthus lacked tori. This observation in combination with other factors serves to isolate this section from the remainder of the genus. Key words: Notelaea, Osmanthus, pit membrane, torus. INTRODUCTION Osmanthus is a member of the Oleaceae (Olive Family), a moderate-sized family with circa 24 genera and 615 spp. (Stevens 2001). There are 33 natural species within the genus (Table 1; Xiang et al. 2008), and they show a tropical to temperate distribution (Bailey & Bailey 1976; Denk et al. 2001; Xiang et al. 2008). Generally, individual shrubs are found in moist forests (Hsieh et al. 1998; Chou et al. 2000; Denk et al. 2001), frequently on steep slopes (Green 1958). In some instances populations are sub- ject to monsoon conditions and hence to periods of relatively low rainfall (Yang et al. 2008; Hua 2008). Tori are thickenings of intervascular pit membranes found not only in gymnosperm, but also in angiosperm wood, including that of Osmanthus (Dute et al. 2008; Dute et al. 2010). Tori were first observed in O. fragrans, O. -

SGAP Cairns Newsletter

SGAP Cairns Newsletter May 2018 Newsletter 179 Editor’s Note Society for Growing Australian Plants, Inc. Cairns Branch. www.sgapcairns.org.au You may have noticed this month’s newsletter is not as [email protected] “flashy” or to the standard we have come to expect each month from our newsletter editor, Stuart, that is because 2018 -2019 Committee he is taking a well earned holiday! However, what we President: Tony Roberts lack in pizzazz we have made up in content! Don has Vice President: Pauline Lawie kindly put together a report on our trip to Ella Bay (which Secretary: Sandy Perkins ([email protected]) was a great day out, btw) and the plant of the month Treasurer: Val Carnie Newsletter: including an interesting google translation. And of Stuart Worboys course, there are the details on our next excursion to ([email protected]) Emerald Creek Falls. Looking forward to seeing you all Webmaster: Tony Roberts in May. Sandy Perkins Excursion Report ELLA BAY (HEATH POINT ) Sunday 15 April 2018 By Don Lawie The beach and dune walk planned for 11 March was cancelled due to heavy rain, local flooding and road washouts. Indeed, damage to Ella Bay Road was so bad that it was closed at Heath Point, the southern arm of Ella Bay, when we arrived on 15 April. Nothing daunted, we set off along the beach but were soon blocked by sharp volcanic rocks so diverted to the road and walked up a steep hill then returned to the beach beyond the rock barrier. The aim of the day was to discover what plants – trees, shrubs, vines etc.- grew in the area with fruits that would conceivably be eaten by shipwrecked mariners who were not knowledgeable about their edibility or otherwise. -

Patterns of Flammability Across the Vascular Plant Phylogeny, with Special Emphasis on the Genus Dracophyllum

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy at Lincoln University by Xinglei Cui Lincoln University 2020 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of philosophy. Abstract Patterns of flammability across the vascular plant phylogeny, with special emphasis on the genus Dracophyllum by Xinglei Cui Fire has been part of the environment for the entire history of terrestrial plants and is a common disturbance agent in many ecosystems across the world. Fire has a significant role in influencing the structure, pattern and function of many ecosystems. Plant flammability, which is the ability of a plant to burn and sustain a flame, is an important driver of fire in terrestrial ecosystems and thus has a fundamental role in ecosystem dynamics and species evolution. However, the factors that have influenced the evolution of flammability remain unclear. -

Structural Diversity and Contrasted Evolution of Cytoplasmic Genomes in Flowering Plants :A Phylogenomic Approach in Oleaceae Celine Van De Paer

Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants :a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae Celine van de Paer To cite this version: Celine van de Paer. Structural diversity and contrasted evolution of cytoplasmic genomes in flowering plants : a phylogenomic approach in Oleaceae. Vegetal Biology. Université Paul Sabatier - Toulouse III, 2017. English. NNT : 2017TOU30228. tel-02325872 HAL Id: tel-02325872 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02325872 Submitted on 22 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REMERCIEMENTS Remerciements Mes premiers remerciements s'adressent à mon directeur de thèse GUILLAUME BESNARD. Tout d'abord, merci Guillaume de m'avoir proposé ce sujet de thèse sur la famille des Oleaceae. Merci pour ton enthousiasme et ta passion pour la recherche qui m'ont véritablement portée pendant ces trois années. C'était un vrai plaisir de travailler à tes côtés. Moi qui étais focalisée sur les systèmes de reproduction chez les plantes, tu m'as ouvert à un nouveau domaine de la recherche tout aussi intéressant qui est l'évolution moléculaire (même si je suis loin de maîtriser tous les concepts...). Tu as toujours été bienveillant et à l'écoute, je t'en remercie. -

Vascular Plants of Pu'uhonua 0 Hiinaunau National

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Technical Report 105 Vascular Plants of Pu'uhonua 0 Hiinaunau National Historical Park Technical Report 106 Birds of Pu'uhonua 0 Hiinaunau National Historical Park COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I AT MANOA Department of Botany 3 190 Maile Way Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822 (808) 956-8218 Clifford W. Smith, Unit Director Technical Report 105 VASCULAR PLANTS OF PU'UHONUA 0 HONAUNAU NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK Linda W. Pratt and Lyman L. Abbott National Biological Service Pacific Islands Science Center Hawaii National Park Field Station P. 0.Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 967 18 University of Hawai'i at Manoa National Park Service Cooperative Agreement CA8002-2-9004 May 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page . LIST OF FIGURES ............................................. 11 ABSTRACT .................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .........................................2 INTRODUCTION ..............................................2 THESTUDYAREA ............................................3 Climate ................................................ 3 Geology and Soils ......................................... 3 Vegetation ..............................................5 METHODS ...................................................5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION .....................................7 Plant Species Composition ...................................7 Additions to the