1 Homer's Entangled Objects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

BSA Annual Report 2012-2013

The British School at Athens Annual Report 2012–2013 THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ATHENS REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 208673 www.bsa.ac.uk PATRON HRH The Prince of Wales CHAIR OF COUNCIL Professor M. Schofield, FBA DIRECTOR Professor C. A. Morgan, OBE, MA, PhD Co-editor of the Annual ATHENS Odos Souedias 52 FRIENDS OF THE BSA (UK) GR 106 76 Athens Hon. Secretaries Professor P. M. Warren School Office Tel: 0030–211–102 2800 Claremont House Fax: 0030–211–102 2803 5 Merlin Haven E-Mail: [email protected] Wotten-under-Edge Fitch Laboratory Tel: 0030–211–102 2830 GL12 7BA E-Mail: [email protected] Friends of the BSA Tel: 0030–211–102 2806 Miss M.-C. Keith E-Mail: [email protected] 12 Sovereign Court 51 Gillingham Street KNOSSOS The Taverna London Villa Ariadne SW1V 1HS Knossos, Herakleion GR 714 09 Crete THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT Tel: 0030–2810–231 993 ATHENS FOUNDATION, USA Fax: 0030–2810–238 495 President Mr L. H. Sackett E-Mail: [email protected] Groton School Box 991 LONDON 10–11 Carlton House Terrace Groton MA 01450 London 8W1Y 5AH Tel: 001–978–448–5205 Tel: 0044–(0)20–7969 5315 Fax: 001–978–448–2348 E-Mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] PUBLICATIONS Co-editor of the Annual Dr S. Sherratt E-Mail: [email protected] Editor of Supplementary Dr O. Krzyszkowska, MA, FSA Volumes/Studies THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ATHENS Chairman’s Report With the death of Hector Catling last February, the British School at fifth decade; and the course for schoolteachers he began was in the Athens has lost one of its most faithful and distinguished servants in 2012–13 session successfully restructured to meet the needs of more all its long history. -

Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1941 Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C. Flowers Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Flowers, Frank C., "Mark Twain's Theories of Morality." (1941). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 99. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/99 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARK TWAIN*S THEORIES OF MORALITY A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College . in. partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Prank C. Flowers 33. A., Louisiana College, 1930 B. A., Stanford University, 193^ M. A., Louisiana State University, 1939 19^1 LIBRARY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COPYRIGHTED BY FRANK C. FLOWERS March, 1942 R4 196 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author gratefully acknowledges his debt to Dr. Arlin Turner, under whose guidance and with whose help this investigation has been made. Thanks are due to Professors Olive and Bradsher for their helpful suggestions made during the reading of the manuscript, E. C»E* 3 7 ?. 7 ^ L r; 3 0 A. h - H ^ >" 3 ^ / (CABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . INTRODUCTION I. Mark Twain— philosopher— appropriateness of the epithet 1 A. -

Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1906 Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 24, Number 04 (April 1906)." , (1906). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/513 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL, 1906 ISO PER YEAR ‘TF'TnTT^ PRICE 15 CENTS 180.5 THE ETUDE 209 MODERN SIX-HAND^ LU1T 1 I1 3 Instruction Books PIANO MUSIC “THE ETUDE” - April, 1906 Some Recent Publications Musical Life in New Orleans.. .Alice Graham 217 FOR. THE PIANOFORTE OF «OHE following ensemb Humor in Music. F.S.Law 218 IT styles, and are usi caching purposes t The American Composer. C. von Sternberg 219 CLAYTON F. SUMMY CO. _la- 1 „ net rtf th ’ standard foreign co Experiences of a Music Student in Germany in The following works for beginners at the piano are id some of the lat 1905...... Clarence V. Rawson 220 220 Wabash Avenue, Chicago. -

WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor

“Weather-Proofing” Shenandoah. Fall, 1974: 18-19. WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor Acknowledgments Some of the poems in this manuscript have previously appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Centennial Review, Colorado Quarterly, Confrontation, Florida Quarterly, The Journal of Popular Film, The Little Magazine, Montana Gothic, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, Southern Poetry Review. Table of Contents I Weather-Proofing A Priest’s Mind . 1 Weather-Proofing . 2 Riding the Earth . 3 Small Consolation . 4 To the Poet as a Young Traveler . 6 The Fact of the Darkness . 7 Outside, Where Films End . 9 On Revisiting Tintern Abbey . 10 The Coming of the Ice: A Sestina . 11 House at the Beach . 13 Postcard from a Daughter in Crete . 15 Spinoza and Dostoevsky Tell Me About My Cousins . 16 Looking for Monday . 17 On the Absence of Moths Underseas . 18 II The Practical Life The Practical Life . 19 Taking the News . 21 In the Best of Health . 22 In the Center of the Soup . 23 Masks . 24 They Who Never Tire . 25 Decorum . 26 After Babi Yar . 27 Death of the Short-Term Memory . 29 Open-Ended . 30 Joys and Desires . 31 Snow on the Louvre . 32 Night Ferry to Helsinki . 33 The Unicorn and the Sea . 35 III Hovering Hovering . 36 Gestorben in Zurich . 37 In the Church of the Frari . 39 Death of an Audio Engineer . 40 For Georgio Morandi . 42 Piano Recital from Second Row Center . 43 In the Shade of Asclepius . 44 The Accident of Recovery . 45 On a Dish from the Ch’ing Dynasty . 46 Swallows on the Moon . -

Letters of Blood and Other Works in English

Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Robert Archambeau (ed.) Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2011 Published on OpenEdition Books: 11 January 2013 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9781906924584 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781906924577 Number of pages: 210 Electronic reference PRINTZ-PÅHLSON, Göran. Letters of Blood and other works in English. New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2011 (generated 19 décembre 2018). Available on the Internet: <http:// books.openedition.org/obp/858>. ISBN: 9781906924584. © Open Book Publishers, 2011 Creative Commons - Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 UK: England & Wales - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU LETTERS OF BLOOD Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon. -

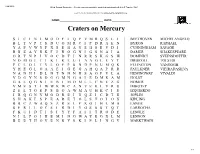

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École De Nancy

La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École de Nancy By Jessica Marie Dandona A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Chair Professor Anne Wagner Professor Andrew Shanken Spring 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Jessica Marie Dandona All rights reserved Abstract La Lorraine Artiste: Nature, Industry, and the Nation in the Work of Émile Gallé and the École de Nancy by Jessica Marie Dandona Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art University of California, Berkeley Professor Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Chair My dissertation explores the intersection of art and politics in the career of 19th-century French designer Émile Gallé. It is commonly recognized that in fin-de-siècle France, works such as commemorative statues and large-scale history paintings played a central role in the creation of a national mythology. What has been overlooked, however, is the vital role that 19th-century arts reformers attributed to material culture in the process of forming national subjects. By educating the public’s taste and promoting Republican values, many believed that the decorative arts could serve as a powerful tool with which to forge the bonds of nationhood. Gallé’s works in glass and wood are the product of the artist’s lifelong struggle to conceptualize just such a public role for his art. By studying decorative art objects and contemporary art criticism, then, I examine the ways in which Gallé’s works actively participated in contemporary efforts to define a unified national identity and a modern artistic style for France. -

ROBSON, Arthur George, 1939- ASPECTS of the HERODOTEAN CONTEXT

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-6363 ROBSON, Arthur George, 1939- ASPECTS OF THE HERODOTEAN CONTEXT. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 Language and Literature, classical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan ASPECTS OF THE HERODOTEAN CONTEXT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Arthur George Robson, B.A., M.A. ******* The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Department of Classics PREFACE This paper grew from one of much briefer compass on Herodotus* philosophy of history; prepared for a graduate seminar at the suggestion of the author but under the stimulation and inspiration of his dissertation adviser, Robert J. Lenardon. 1 can indirectly indicate the quality of guidance afforded me by saying that a lover of Thucydides inculcated a love of Herodotus. Whether such fair-mindedness and high-minded objectivity derives more from the example of Herodotus or of Thucydides is a moot point which the two of us resolve in quietly opposed ways. This continually growing interest then in why Herodotus wrote what he wrote in the way he did produced the present study. I do not of course presume to furnish the definitive answer to these questions. 1 have rather chosen simply to reflect upon important aspects of these topics in an organized fashion. The emphasis of my own studies has been literary and philosophical; and accordingly the present work represents this emphasis. From these two vantage ii points X have dealt more with Herodotus the historian than I have the history of Herodotus. -

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth

Wandering Poets and the Dissemination of Greek Tragedy in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC Edmund Stewart Abstract This work is the first full-length study of the dissemination of Greek tragedy in the earliest period of the history of drama. In recent years, especially with the growth of reception studies, scholars have become increasingly interested in studying drama outside its fifth century Athenian performance context. As a result, it has become all the more important to establish both when and how tragedy first became popular across the Greek world. This study aims to provide detailed answers to these questions. In doing so, the thesis challenges the prevailing assumption that tragedy was, in its origins, an exclusively Athenian cultural product, and that its ‘export’ outside Attica only occurred at a later period. Instead, I argue that the dissemination of tragedy took place simultaneously with its development and growth at Athens. We will see, through an examination of both the material and literary evidence, that non-Athenian Greeks were aware of the works of Athenian tragedians from at least the first half of the fifth century. In order to explain how this came about, I suggest that tragic playwrights should be seen in the context of the ancient tradition of wandering poets, and that travel was a usual and even necessary part of a poet’s work. I consider the evidence for the travels of Athenian and non-Athenian poets, as well as actors, and examine their motives for travelling and their activities on the road. In doing so, I attempt to reconstruct, as far as possible, the circuit of festivals and patrons, on which both tragedians and other poetic professionals moved.