A Study of JS Bach's Toccata in E Minor, BWV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

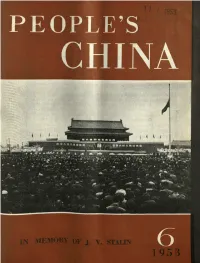

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

Frescobaldi Gesualdo Solbiati

Frescobaldi Gesualdo Solbiati FRANCESCO GESUALDI Accordion Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 -1643) If we think of the theatre as a place in which audiences not only perceive with their eyes and ears, but also their deeper feelings, then the work presented in this recording Dal II Libro di Toccate is in many respects theatrical. The explanation lies in the fact that one of Francesco 1. Toccata I 4’42 Gesualdi’s particular gifts as a performer is his ability to produce sounds that conjure 2. Toccata II 4’44 up the action underlying the music, and indeed evoke the spaces in which the events 3. Toccata III, da sonarsi alla Levatione 8’51 take place. This is particularly noteworthy when performance is actually separated 4. Toccata IV, da sonarsi alla Levatione 6’58 from the reality of visualization. 5. Toccata VIII, di Durezze e Ligature 5’01 The synaesthetic experience underlying vision and visionary perception is arguably one of the fundamental ingredients of the “Second Practice”, or stile moderno, which Dal I Libro di Toccate aimed at engaging the feelings of the listener. This art was essential to the evocative 6. Partite sopra l'Aria della Romanesca (1–14) 21’49 power of Frescobaldi’s music. In his performance Francesco Gesualdi establishes a particular spatial and temporal Carlo Gesualdo (1566–1613) universe in which the constraints of absolute formal rigour are reconciled with 7. Canzon francese del Principe 6’40 freedom of accentuation and vital breath, so as to invest each execution with the immediacy of originality. In this ability to renew with each rendering, Gesualdi’s Alessandro Solbiati (1956) playing speaks for the way wonderment can forge the essential relationship between 8. -

Key Relationships in Music

LearnMusicTheory.net 3.3 Types of Key Relationships The following five types of key relationships are in order from closest relation to weakest relation. 1. Enharmonic Keys Enharmonic keys are spelled differently but sound the same, just like enharmonic notes. = C# major Db major 2. Parallel Keys Parallel keys share a tonic, but have different key signatures. One will be minor and one major. D minor is the parallel minor of D major. D major D minor 3. Relative Keys Relative keys share a key signature, but have different tonics. One will be minor and one major. Remember: Relatives "look alike" at a family reunion, and relative keys "look alike" in their signatures! E minor is the relative minor of G major. G major E minor 4. Closely-related Keys Any key will have 5 closely-related keys. A closely-related key is a key that differs from a given key by at most one sharp or flat. There are two easy ways to find closely related keys, as shown below. Given key: D major, 2 #s One less sharp: One more sharp: METHOD 1: Same key sig: Add and subtract one sharp/flat, and take the relative keys (minor/major) G major E minor B minor A major F# minor (also relative OR to D major) METHOD 2: Take all the major and minor triads in the given key (only) D major E minor F minor G major A major B minor X as tonic chords # (C# diminished for other keys. is not a key!) 5. Foreign Keys (or Distantly-related Keys) A foreign key is any key that is not enharmonic, parallel, relative, or closely-related. -

Download Program Notes

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky t should come as no surprise that Pyotr Ily- background to this piece, which involved Iich Tchaikovsky approached his Fifth Sym- resignation to fate, the designs of provi- phony from a position of extreme self-doubt, dence, murmurs of doubt, and similarly since that was nearly always his posture vis- dark thoughts. à-vis his incipient creations. In May 1888 he Critics blasted the symphony at its pre- confessed in a letter to his brother Modest miere, due in part to the composer’s limited that he feared his imagination had dried up, skill on the podium; and yet the audience that he had nothing more to express in mu- was enthusiastic. Predictably, Tchaikovsky sic. Still, there was a glimmer of optimism: “I decided the critics must be right. In Decem- am hoping to collect, little by little, material ber he wrote to von Meck: for a symphony,” he wrote. Tchaikovsky spent the summer of 1888 Having played my Symphony twice in Pe- at a vacation home he had built on a forest- tersburg and once in Prague, I have come ed hillside at Frolovskoe, not far from his to the conclusion that it is a failure. There home base in Moscow. The idyllic locale ap- is something repellent in it, some over- parently played a major role in his manag- exaggerated color, some insincerity of ing to complete this symphony in the span fabrication which the public instinctive- of four months. Tchaikovsky made a habit ly recognizes. It was clear to me that the of keeping his principal patron, Nadezhda applause and ovations referred not to von Meck, informed about his compositions this but to other works of mine, and that through detailed letters, and thanks to this the Symphony itself will never please ongoing correspondence a good deal of in- the public. -

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

From Proletarian Internationalism to Populist

from proletarian internationalism to populist russocentrism: thinking about ideology in the 1930s as more than just a ‘Great Retreat’ David Brandenberger (Harvard/Yale) • [email protected] The most characteristic aspect of the newly-forming ideology... is the downgrading of socialist elements within it. This doesn’t mean that socialist phraseology has disappeared or is disappearing. Not at all. The majority of all slogans still contain this socialist element, but it no longer carries its previous ideological weight, the socialist element having ceased to play a dynamic role in the new slogans.... Props from the historic past – the people, ethnicity, the motherland, the nation and patriotism – play a large role in the new ideology. –Vera Aleksandrova, 19371 The shift away from revolutionary proletarian internationalism toward russocentrism in interwar Soviet ideology has long been a source of scholarly controversy. Starting with Nicholas Timasheff in 1946, some have linked this phenomenon to nationalist sympathies within the party hierarchy,2 while others have attributed it to eroding prospects for world This article builds upon pieces published in Left History and presented at the Midwest Russian History Workshop during the past year. My eagerness to further test, refine and nuance this reading of Soviet ideological trends during the 1930s stems from the fact that two book projects underway at the present time pivot on the thesis advanced in the pages that follow. I’m very grateful to the participants of the “Imagining Russia” conference for their indulgence. 1 The last line in Russian reads: “Bol’shuiu rol’ v novoi ideologii igraiut rekvizity istoricheskogo proshlogo: narod, narodnost’, rodina, natsiia, patriotizm.” V. -

Onomastica Uralica 8

ONOMASTICA PatrocinySettlementNames inEurope Editedby VALÉRIA TÓTH Debrecen–Helsinki 2011 Onomastica Uralica President of the editorial board István Nyirkos, Debrecen Co-president of the editorial board Ritva Liisa Pitkänen, Helsinki Editorial board Terhi Ainiala, Helsinki Sándor Maticsák, Debrecen Tatyana Dmitrieva, Yekaterinburg Irma Mullonen, Petrozavodsk Kaisa Rautio Helander, Aleksej Musanov, Syktyvkar Guovdageaidnu Peeter Päll, Tallinn István Hoffmann, Debrecen Janne Saarikivi, Helsinki Marja Kallasmaa, Tallinn Valéria Tóth, Debrecen Nina Kazaeva, Saransk D. V. Tsygankin, Saransk Lyudmila Kirillova, Izhevsk The articles were proofread by Terhi Ainiala, Helsinki Andrea Bölcskei, Budapest Christian Zschieschang, Leipzig Lector of translation Jeremy Parrott Technical editor Valéria Tóth Cover design and typography József Varga The work is supported by the TÁMOP 4.2.1./B-09/1/KONV-2010-0007 project. The project is implemented through the New Hungary Development Plan, co-financed by the European Social Fund and the European Regional Development Fund. The studies are to be found at the Internet site http://mnytud.arts.unideb.hu/onomural/ ISSN 1586-3719 (Print), ISSN 2061-0661 (Online) ISBN 978-963-318-126-3 Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó University of Debrecen Publisher: Márta Virágos, Director General of University and National Library, University of Debrecen. Contents Foreword ................................................................................................... 5 PIERRE -HENRI BILLY Patrociny Settlement Names in France .............................................. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College A

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A PEDAGOGICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO PROKOFIEV’S FOUR PIECES, OP. 32 A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By IVAN D. HURD III Norman, Oklahoma 2017 A PEDAGOGICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO PROKOFIEV’S FOUR PIECES, OP. 32 A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Jane Magrath, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Barbara Fast ______________________________ Dr. Jeongwon Ham ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon ______________________________ Dr. Caleb Fulton Dr. Click here to enter text. © Copyright by IVAN D. HURD III 2017 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The number of people that deserve recognition for their role in completing not only this document, but all of my formal music training and education, are innumerable. Thank you to the faculty members, past and present, who have served on my doctoral committee: Dr. Jane Magrath (chair), Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Jeongwon Ham, Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Rachel Lumsden, and Dr. Caleb Fulton. Dr. Magrath, thank you for inspiring me, by your example, to find the absolute best possible version of myself as a pianist, educator, collaborator, writer, and scholar. I am incredibly grateful to have had the opportunity to study with you on a weekly basis in lessons, to develop and hone my teaching skills through your guidance in pedagogy classes and observed lessons, and for your encouragement throughout every aspect of the degree. Dr. Fast, I especially appreciate long conversations about group teaching, your inspiration to try new things and be creative in the classroom, and for your practical career advice. -

Max Reger's Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Carole Terry, Chair Jonathan Bernard Craig Sheppard Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Wyatt Smith ii University of Washington Abstract Max Reger’s Adaptations of Bach Keyboard Works for the Organ Wyatt Smith Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Carole Terry School of Music The history and performance of transcriptions of works by other composers is vast, largely stemming from the Romantic period and forward, though there are examples of such practices in earlier musical periods. In particular, the music of Johann Sebastian Bach found its way to prominence through composers’ pens during the Romantic era, often in the form of transcriptions for solo piano recitals. One major figure in this regard is the German Romantic composer and organist Max Reger. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Reger produced many adaptations of works by Bach, including organ works for solo piano and four-hand piano, and keyboard works for solo organ, of which there are fifteen primary adaptations for the organ. It is in these adaptations that Reger explored different ways in which to take these solo keyboard works and apply them idiomatically to the organ in varying degrees, ranging from simple transcriptions to heavily orchestrated arrangements. This dissertation will compare each of these adaptations to the original Bach work and analyze the changes made by Reger. It also seeks to fill a void in the literature on this subject, which often favors other areas of Reger’s transcription and arrangement output, primarily those for the piano.