Assessment of the Sin Tax Reform Act of 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microorganisms in Fermented Foods and Beverages

Chapter 1 Microorganisms in Fermented Foods and Beverages Jyoti Prakash Tamang, Namrata Thapa, Buddhiman Tamang, Arun Rai, and Rajen Chettri Contents 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.1 History of Fermented Foods ................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 History of Alcoholic Drinks ................................................................................... 4 1.2 Protocol for Studying Fermented Foods ............................................................................. 5 1.3 Microorganisms ................................................................................................................. 6 1.3.1 Isolation by Culture-Dependent and Culture-Independent Methods...................... 8 1.3.2 Identification: Phenotypic and Biochemical ............................................................ 8 1.3.3 Identification: Genotypic or Molecular ................................................................... 9 1.4 Main Types of Microorganisms in Global Food Fermentation ..........................................10 1.4.1 Bacteria ..................................................................................................................10 1.4.1.1 Lactic Acid Bacteria .................................................................................11 1.4.1.2 Non-Lactic Acid Bacteria .........................................................................11 -

Signalling Virtue, Promoting Harm: Unhealthy Commodity Industries and COVID-19

SIGNALLING VIRTUE, PROMOTING HARM Unhealthy commodity industries and COVID-19 Acknowledgements This report was written by Jeff Collin, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Rob Ralston, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Sarah Hill, Global Health Policy Unit, University of Edinburgh, SPECTRUM; Lucinda Westerman, NCD Alliance. NCD Alliance and SPECTRUM wish to thank the many individuals and organisations who generously contributed to the crowdsourcing initiative on which this report is based. The authors wish to thank the following individuals for contributions to the report and project: Claire Leppold, Rachel Barry, Katie Dain, Nina Renshaw and those who contributed testimonies to the report, including those who wish to remain anonymous. Editorial coordination: Jimena Márquez Design, layout, illustrations and infographics: Mar Nieto © 2020 NCD Alliance, SPECTRUM Published by the NCD Alliance & SPECTRUM Suggested citation Collin J; Ralston R; Hill SE, Westerman L (2020) Signalling Virtue, Promoting Harm: Unhealthy commodity industries and COVID-19. NCD Alliance, SPECTRUM Table of contents Executive Summary 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Our approach to mapping industry responses 7 Using this report 9 CHAPTER I ADAPTING MARKETING AND PROMOTIONS TO LEVERAGE THE PANDEMIC 11 1. Putting a halo on unhealthy commodities: Appropriating front line workers 11 2. ‘Combatting the pandemic’ via marketing and promotions 13 3. Selling social distancing, commodifying PPE 14 4. Accelerating digitalisation, increasing availability 15 CHAPTER II CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND PHILANTHROPY 18 1. Supporting communities to protect core interests 18 2. Addressing shortages and health systems strengthening 19 3. Corporate philanthropy and COVID-19 funds 21 4. Creating “solutions”, shaping the agenda 22 CHAPTER III PURSUING PARTNERSHIPS, COVETING COLLABORATION 23 1. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia

Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia Foodways can reveal the strongest and deepest traces of human history and culture, and this pioneering volume is a detailed study of the development of the traditional dietary culture of Southeast Asia from Laos and Vietnam to the Philippines and New Guinea from earliest times to the present. Being blessed with abundant natural resources, dietary culture in Southeast Asia flourished during the pre- European period on the basis of close relationships between the cultural spheres of India and China, only to undergo significant change during the rise of Islam and the age of European colonialism. What we think of as the Southeast Asian cuisine today is the result of the complex interplay of many factors over centuries. The work is supported by full geological, archaeological, biological and chemical data, and is based largely upon Southeast Asian sources which have not been available up until now. This is essential reading for anyone interested in culinary history, the anthropology of food, and in the complex history of Southeast Asia. Professor Akira Matsuyama graduated from the University of Tokyo. He later obtained a doctorate in Agriculture from that university, later becoming Director of Radiobiology at the Institute of Physical and Chemical research. After working in Indonesia he returned to Tokyo's University of Agriculture as Visiting Professor. He is currently Honorary Scientist at the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, Tokyo. This page intentionally left blank Traditional Dietary Culture of Southeast Asia Its Formation and Pedigree Akira Matsuyama Translated by Atsunobu Tomomatsu Routledge RTaylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published by Kegan Paul in 2003 This edition first published in 2009 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint o f the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2003 Kegan Paul All rights reserved. -

TAGABAWA-ENGLISH DICTIONARY Carl D

a 1 abuk TAGABAWA-ENGLISH DICTIONARY Carl D. DuBois Summer Institute of Linguistics July 13, 2016 For someone (SF:actor m-) to make do with something A (OF:patient -n). Igabé dé igkan. We went ahead to eat it a pron. (First person singular, set 1) I. anyway. Atin ándà ássa, abén ta aán (var. of ahà + -án) dád ni kannun. If there is no other, we will just have to make abas n. Measles. do with this one. v. For someone (IDF:st.loc. k--an) to be afflicted with measles. abô [a’bô ], ébô, ibô conj. So that. abasán (derv.) n. Someone abri (Sp. abri) v. For someone (SF:actor who is afflicted with measles. m-) to open something (???:???) (door) somewhere or to abád n. Welts from whipping. something (DF:dir. -han) v. For someone or something (a abu n. Ashes. whip) (ISF:st.actor/inst. mak-) to Hearth. [The place in the kitchen inflict welts. where the cooking fire is built.] For someone (IDF:st.loc. k--dan) to v. For someone (SF:actor m-) to be afflicted with welts from clean something (kettle) whipping. cf. lagpás {PL} (DF:dir. -wan) with ashes. abál v. For someone (SF:actor m-) to cf. siggang weave cloth abug 1 [a’bug ] (Ceb.) n. Dust on ground (OF:patient=all -lán). or floor. For someone (SF:actor m-) to weave v. For something (IDF:st.loc. k--an) cloth (DF:loc.=part -lan). to be dusty. cf. barukbuk inabál (derv.) n. Cloth woven abugán (derv.) n. Something of abaca fiber. -

Sampoerna University

SU Catalogue 2018-2019 1 WELCOME TO SAMPOERNA UNIVERSITY Welcome to Sampoerna University. We would like to congratulate each of you, our students, for your achievement in As the future of Indonesia lies in your hands, we hope that you will use your time becoming a member of the Sampoerna University community. here at Sampoerna University to gain the knowledge and skills required when you enter the professional world. It is a world where you will have to compete in Sampoerna University will provide you with an international education as you the labor force in all the ASEAN countries and beyond. study the discipline of your choice. We have established collaborations with overseas universities to ensure that you will have a pathway to your future In addition to knowledge, we hope that you will develop comprehensive social with international recognition. Our campus is the ideal place for developing and skills and moral values that will empower you to make meaningful contributions achieving your intellectual potential. to your community. Social competencies include empathy and awareness of other people, ability to listen to and understand disparate views, as well as to You will follow the learning process in different study programs in a broad range communicate across social differences. With these social competencies, we are of subjects. However, the variety of these subjects should not segregate you from confident that our students can work as a team, assume constructive roles in your fellow students undertaking other study programs. The interdisciplinary the community, and become wise and caring human beings. courses and dialogue between all fields of study are at the core of our curriculum. -

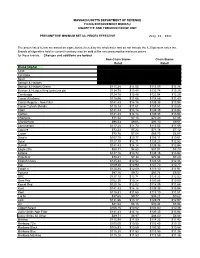

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

45000033237 Output.O.Pdf

ti •>• TO #! • fj É ttwm aA I '.um MCI H IJB PME ÍPÍS 0 1® •V^k- 91 INfa At •aOE • 9 .-• * .*' iC s rjítt .» *. *%' f ;•*, ».• &*• -Kv- ^^o ^ 'h^ REVISTA XXA. BRAZILEIRA • DIRIGIDA ECOLLABORADA POR MELLO MORAES FILHO DESENHOS HUASCAR DE VERGARA GRAVURAS / ALFREDO PINHEIRO & VILLASBOAS OLíMPÍo^v^í. RIO DE JANEIRO Typographia de PINHEIRO & C. Rua Sete de-Setembro n. 157 1882 O estudo do homem primitivo do antigo continente, do qual ninguém cuidou ! até o começo do presente século, desenvolveu-se subitamente por ultimo, e de tal fôrma, que mister se fez tornal-o extensivo ás raças que senhoreavam o vasto continente americano quando o gênio de Colombo logrou desvendar o acanhado mundo conhecido de seus coevos, os largos horizontes do immenso hemispherio do occidente. O Novo Mundo, exornado de tamanhas e tão ignotas louçanias, offerecia no seu largo seio de millenarias matadas— primogênitas da terra—, de rios-oceanos de cordilheiras .inaccessiveis e de planieies incommensuraveis, todas as phases gradualmente percorridas pela humanidade do antigo hemispherio na sua ascensional intelectualidade. Creaturas ahi havia que do homem só possuíam a feição e a natureza physica; indivíduos que tinham na quasi privação da linguagem modulativa e expressora do pensamento, nos gestos toscos e nos costumes símios, boa parte do caracter dos brutos cora os quaes conviviam e privavam em promiscua ferocidade. Seriam taes entidades a primeira fôrma plástica—o blastoderma psychologico da individualidade hu mana—, ou representariam pelo contrario o embrutecimento -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-84489-5 — A Concise History of Greece Richard Clogg Frontmatter More Information cambridge concise histories A Concise History of Greece Now reissued in a fourth, updated edition, this book provides a concise, illustrated introduction to the modern history of Greece, from the irst stirrings of the national movement in the late eighteenth century to the present day. As Greece emerges from a devastating economic crisis, this fourth edition offers analyses of contemporary political, economic and social devel- opments. It includes additional illustrations, together with updated tables and suggestions for further reading. A new concluding chapter considers the trajectory of Greek history over the two hundred years since the beginning of the War of Independence in 1821. Designed to provide a basic introduc- tion, the irst edition of this hugely successful Concise History won the Runciman Award for a best book on an Hellenic topic in 1992 and has been translated into thirteen languages, including all the languages of the Balkans. richard clogg has been lecturer in Modern Greek History at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies and King’s College, University of London; Reader in Modern Greek History at King’s College; and Professor of Modern Balkan History in the University of London. From 1990 to 2005 he was a Fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford, of which he is now an Emeritus Fellow. He has written extensively on Greek history and politics from the eighteenth century to the present. His most recent book is Greek to Me: A Memoir of Academic Life (2018). -

Altria Group, Inc. 2013 Annual Report

Altria Group, Inc. 2013 Annual Report altria.com Altria’s Operating Companies Philip Morris USA Inc. (PM USA) Philip Morris USA is the largest tobacco company in the U.S. and has about half of the U.S. cigarette market’s retail share. Altria Group, Inc. U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company LLC (USSTC) U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company is the n an Altria Company largest producer and marketer of moist Annual Report 2013 smokeless tobacco, one of the fastest growing tobacco segments in the U.S. John Middleton Co. (Middleton) John Middleton is a leading manufacturer of machine-made large cigars and pipe tobacco. Ste. Michelle Wine Estates Ltd. (Ste. Michelle) Ste. Michelle Wine Estates ranks among the top-ten producers of premium wines in the U.S. Nu Mark LLC (Nu Mark) Nu Mark is focused on responsibly developing and marketing innovative tobacco products for adult tobacco consumers. Philip Morris Capital Corporation (PMCC) Philip Morris Capital Corporation manages an existing portfolio of leveraged and direct finance lease investments. Altria Group, Inc. 6601 W. Broad Street Richmond, VA 23230-1723 Our Mission is to own and develop financially disciplined Shareholder Information businesses that are leaders in responsibly providing adult tobacco and wine consumers with superior branded products. Shareholder Response Center: Direct Stock Purchase and If you do not have Internet Stock Computershare Trust Company, Dividend Reinvestment Plan: access, you may call: Exchange Listing: N.A. (Computershare), our trans- Altria Group, Inc. offers a Direct 1-804-484-8222 The principal stock fer agent, will be happy to answer Stock Purchase and Dividend exchange on which questions about your accounts, Reinvestment Plan, administered Internet Access Altria Group, Inc.’s certificates, dividends or the by Computershare. -

DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE, Iskay Simipi Yuyayk'ancha

DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE Iskay simipi yuyayk’ancha Quechua – Castellano Castellano – Quechua Teofilo Laime Ajacopa Segunda edición mejorada1 Ñawpa yanapaqkuna: Efraín Cazazola Félix Layme Pairumani Juk ñiqi p’anqata ñawirispa allinchaq: Pedro Plaza Martínez La Paz - Bolivia Enero, 2007 1 Ésta es la version preliminar de la segunda edición. Su mejoramiento todavía está en curso, realizando inclusión de otros detalles lexicográficos y su revisión. 1 DICCIONARIO BILINGÜE CONTENIDO Presentación por Xavier Albo 2 Introducción 5 Diccionarios quechuas 5 Este diccionario 5 Breve historia del alfabeto 6 Posiciones de consonantes en el plano fonológico del quechua 7 Las vocales quechuas y aimaras 7 Para terminar 8 Bibliografía 8 Nota sobre la normalización de las entradas léxicas 9 Abreviaturas y símbolos usados 9 Diccionario quechua - castellano 10 A 10 KH 47 P 75 S 104 CH 18 K' 50 PH 81 T 112 CHH 24 L 55 P' 84 TH 117 CH' 26 LL 57 Q 86 T' 119 I 31 M 62 QH 91 U 123 J 34 N 72 Q' 96 W 127 K 41 Ñ 73 R 99 Y 137 Sufijos quechuas 142 Diccionario castellano - quechua 145 A 145 I 181 O 191 V 208 B 154 J 183 P 193 W 209 C 156 K 184 Q 197 X 210 D 164 L 184 R 198 Y 210 E 169 LL 186 RR 202 Z 211 F 175 M 187 S 202 G 177 N 190 T 205 H 179 Ñ 191 U 207 Sufijos quechuas 213 Bibliografía 215 Datos biográficos del autor 215 LICENCIA Se puede copiar y distribuir este libro bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Atribución-LicenciarIgual 2.5 con atribución a Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Efraín Cazazola, Félix Layme Pairumani y Pedro Plaza Martínez. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg.