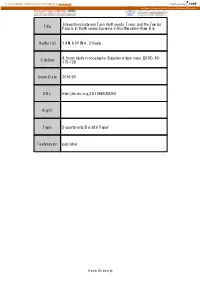

Randi-Markusen-Botsw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: a Case for an Apology and Reparations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal June 2017 /SPECIAL/ edition ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Ovaherero/Nama Genocide: A Case for an Apology and Reparations Nick Sprenger Robert G. Rodriguez, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce Ngondi A. Kamaṱuka, PhD University of Kansas Abstract This research examines the consequences of the Ovaherero and Nama massacres occurring in modern Namibia from 1904-08 and perpetuated by Imperial Germany. Recent political advances made by, among other groups, the Association of the Ovaherero Genocide in the United States of America, toward mutual understanding with the Federal Republic of Germany necessitates a comprehensive study about the event itself, its long-term implications, and the more current vocalization toward an apology and reparations for the Ovaherero and Nama peoples. Resulting from the Extermination Orders of 1904 and 1905 as articulated by Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Imperial Germany, over 65,000 Ovaherero and 10,000 Nama peoples perished in what was the first systematic genocide of the twentieth century. This study assesses the historical circumstances surrounding these genocidal policies carried out by Imperial Germany, and seeks to place the devastating loss of life, culture, and property within its proper historical context. The question of restorative justice also receives analysis, as this research evaluates the case made by the Ovaherero and Nama peoples in their petitions for compensation. Beyond the history of the event itself and its long-term effects, the paper adopts a comparative approach by which to integrate the Ovaherero and Nama calls for reparations into an established precedent. -

Redressing Colonial Genocide: the Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany

Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 2005 Redressing Colonial Genocide: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany Rachel J. Anderson University of Nevada, Las Vegas -- William S. Boyd School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Rachel J., "Redressing Colonial Genocide: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany" (2005). Scholarly Works. 288. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/288 This Response or Comment is brought to you by the Scholarly Commons @ UNLV Boyd Law, an institutional repository administered by the Wiener-Rogers Law Library at the William S. Boyd School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany Rachel Andersont INTRODUCTION It is widely supposed that the genocidal wars waged by colonial ad- ministrations against indigenous peoples or nations before 1948 did not violate rules of international law. Contemporary scholars and commenta- tors assert that all forms of genocide were first criminalized and made pun- ishable by the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide (U.N. Genocide Convention).' As a result, schol- ars argue that wars of annihilation2 perpetrated by colonial administrations were not illegal acts under contemporaneous international law.3 The Copyright © 2005 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. t Juris Doctor candidate, School of Law, University of California, Berkeley (Boalt Hall), 2005; Masters in International Policy Studies, Stanford University, 2002; Zwischenprufung, Humboldt University, Berlin, 1998. -

The Homecoming of Ovaherero and Nama Skulls: Overriding Politics And

i i i The homecoming of Ovaherero and i Nama skulls: overriding politics and injustices HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Vilho Amukwaya Shigwedha The University of Namibia [email protected] Abstract In October 2011, twenty skulls of the Herero and Nama people were repatriated from Germany to Namibia. So far, y-ve skulls and two human skeletons have been repatriated to Namibia and preparations for the return of more skulls from Germany were at an advanced stage at the time of writing this article. Nonetheless, the skulls and skeletons that were returned from Germany in the past have been disappointingly laden with complexities and politics, to such an extent that they have not yet been handed over to their respective communities for mourning and burials. In this context, this article seeks to investigate the practice of ‘anonymis- ing’ the presence of human remains in society by exploring the art and politics of the Namibian state’s memory production and sanctioning in enforcing restrictions on the aected communities not to perform, as they wish, their cultural and ritual practices for the remains of their ancestors. Key words: Skulls, Herero, Nama, genocide, Germany, Namibia Introduction Until 1919, today’s Namibia was ocially the colony of German South West Africa (GSWA). This came as a result of the 1884/85 Berlin Conference, which formally recognised Germany’s right to operate in and colonise the territory that it renamed GSWA.1 German colonial occupation of this territory, which was renamed Namibia in 1968, lasted from 1885 until 1919, when Imperial Germany was defeated in the First World War and subsequently lost her colonies in Africa. -

Britain's Response to the Herero and Nama Genocide, 1904-07

Britain’s Response to the Herero and Nama Genocide, 1904-07 A Realist Perspective on Britain’s Assistance to Germany During the Genocide in German South-West Africa Daniel Grimshaw Master thesis in Holocaust and Genocide Studies Supervisor: Dr. Tomislav Dulić Submission date: 25/09/2014 Credits: 45 Abstract This thesis investigates the British response to the Herero and Nama genocide, committed in German South-West Africa, now Namibia in 1904-07. The records of the British Foreign Office will be used to assess Britain’s response to the atrocities. This thesis will determine how much the British authorities knew about the events at the time, the effects of the war on the British colonies in South Africa, the ways in which the British helped the Germans, why they helped the Germans and why there was no intervention. The theory of realism will be applied to explain why the British authorities acted the way they did, whilst using Hyam’s interaction model to demonstrate how decisions were made in the British Empire. This thesis demonstrates that the British Foreign Office co-operated with Germany for its own self interest and was indifferent to the suffering of the Herero and Nama as realpolitik dictated Britain’s response to the events. 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my family for their continued support throughout my master’s degree and who are always behind me in whatever I do. I especially thank my sister who gave me valuable criticism in the draft of this thesis. I also thank Professor Henning Melber who provided great wisdom and insight about the genocide during our discussions. -

Genocide of the Herero and Nama, 1904-1907

Genocide of The Herero and Nama, 1904-1907 What The genocide of the Herero and Nama in Africa, perpetrated by Germany during the Second Reich, is largely unknown. Germany had colonial control of an area known as German Southwest Africa. Between 1904 and 1907, German military forces committed genocide against that country’s indigenous populations to gain control over the land The German government ordered the murder of the indigenous Herero and Nama people through battle, forced starvation, forced dehydration, sexual violence, life-threatening medical experiments, and incarceration in concentration camps. These actions became the blueprint for Germany’s strategies to exterminate Jews and other targeted populations during the Namibia Holocaust of World War II, 1933-1945. While record-keeping from the period makes it difficult to quantify the total loss of life, it is estimated that 80% of the Herero people and 50% of the Nama people perished over the three-year genocide. Where Namibia is located in southern Africa and is bordered by South Africa, Botswana, Angola, Zambia, and the Atlantic Ocean. The area was a German settler colony, and many Germans moved there in search of farmland at a time of scarcity of arable land in Germany. In 1915, during World War I, South Africa began a military occupation of the country, officially ending Germany’s colonial rule. South Africa maintained apartheid-style control over Namibia until Namibian independence was won in 1990 after extended and brutal conflict. How In 1904, leaders of the Herero attacked a German fort in the town of Okahandja in protest of German policies. -

The Maternal Genetic History of the Angolan Namib Desert: a Key Region For

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/162230; this version posted July 11, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The maternal genetic history of the Angolan Namib Desert: a key region for 2 understanding the peopling of southern Africa 3 4 Sandra Oliveira1,2, Anne-Maria Fehn1,3,4, Teresa Aço5, Fernanda Lages6, Magdalena Gayà-Vidal1, Brigitte 5 Pakendorf7, Mark Stoneking8, Jorge Rocha1,2,6 6 7 1. CIBIO/InBIO: Research Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources, University of Porto, Portugal 8 2. Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Portugal 9 3. Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution, MPI for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany 10 4. Institute for African Studies, Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany 11 5. Centro de Estudos do Deserto (CEDO), Namibe, Angola 12 6. ISCED/Huíla—Instituto Superior de Ciências da Educação, Lubango, Angola 13 7. Laboratoire Dynamique du Langage, UMR5596, CNRS & Univ Lyon, Lyon, France 14 8. Department of Evolutionary Genetics, MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany 15 16 Corresponding author: Jorge Rocha 17 Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/162230; this version posted July 11, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Taboos Related to the Ancestors of the Himba and Herero Pastoralists in Northwest Namibia: a Preliminary Report

Taboos Related to the Ancestors of the Himba and Herero Pastoralists in Northwest Namibia: A Preliminary Report Kana MIYAMOTO Graduate School of Intercultural Studies, Kobe University, Kobe, Japan This preliminary report summarizes first-hand data on taboos shared by the Himba and Herero pastoralists, living in northwest Namibia. By dealing with taboos related to their ancestors, I aim to clarify the relationship between the pastoralists and their ancestors. In previous studies, the relationship between the Himba and Herero and their ancestors often focused on the gravesite and the commemoration ceremony, which were often drawn from a political context. This paper, on the other hand, will present the relationship with the ancestors and the taboos shared among people. Taboos related to the ancestors can be roughly classified into two types, one related to the patrilineal clan and the other to a specific space called the “holy place” (otjirongo tjizera). Certain patrilineal clans associate with specific areas through the “ancestral shrine” (okuruwo) located inside their homestead. The relationship between the holy place and the patrilineal clan has not been clearly mentioned by people living in the area. Taboos related to the holy place are not limited to a specific patrilineal clan; anyone who is in that place must obey the taboos. However, there have been cases where elders, responsible for the patrilineal clan’s rituals at the ancestral shrine, treated those who broke the taboos inside the holy place. I have examined the relationship of the ancestors and the specific places of the semi-nomadic people, the Himba and Herero. Keywords: taboo, ancestor, cognition of space, Himba, Herero INTRODUCTION This preliminary report summarizes first-hand data on taboos shared among Himba and Herero pastoralists living in northwest Namibia1. -

0119 Southernafricadoc110co

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Edited by Robert Hitchcock and Diana Vinding IWGIA Document No. 110 - Copenhagen 2004 3 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA Editors: Robert K. Hitchcock and Diana Vinding Copyright: IWGIA 2004 – All Rights Reserved Cover design, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks/Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 87-91563-08-9 Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org 4 This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 CONTENTS Introduction Robert K. Hitchcock and Diana Vinding ......................................8 1. The Indigenous Peoples of Southern Africa: An Overview Sidsel Saugestad ...............................................................................22 NAMIBIA 2. Indigenous Rights in Namibia Clement Daniels ...............................................................................44 3. Indigenous Land Rights and Land Reform in Namibia Sidney L. Harring ............................................................................63 4. Civil Rights in Legislation and Practice – A Case Study from Tsumkwe District West, Namibia Richard Pakleppa with inputs from the WIMSA team ..............................................82