The Politics of Genocide Reparations Claims in Namibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Windhoek, Namibia Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Windhoek, Namibia Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA NAMIBIA Population: 2,533,224 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 1.91% (2018) Median Age: 21.4 GDP: USD$29.6 billion (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita: USD$11,200 (2017 est.) City of Intervention: Windhoek Urban Population: 50% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.2% annual rate of change (2015- 2020 est.) Land Area: 910,768 sq km Total Roadways: 48,327 km (2014) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi-Scalar Governance Following a 25-year war, Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 under the rule of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Since then, SWAPO has held the presidency, prime minister’s office, the national assembly, and most local and regional councils by a large majority. While opposition parties are active (there are over ten groups), they remain weak and fragmented, with most significant political differences negotiated within SWAPO. The constitution and other legislation dating to the early 1990s emphasize the role of regional and local councils – and since 1998, the government has been engaged in efforts to support decentralization of power.1 However, all levels are connected by SWAPO (through common membership), so power remains effectively centralized. -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Caleb Joseph Cumberland Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the African History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Legal History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cumberland, Caleb Joseph, "Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 249. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/249 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Caleb Joseph Cumberland Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my gratitude to my senior project advisor, Professor Drew Thompson, as without his guidance I would not have been able to complete such a project. -

RUMOURS of RAIN: NAMIBIA's POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre Du Pisani

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani THE .^-y^Vr^w DIE SOUTH AFRICAN i^W*nVv\\ SUID AFRIKAANSE INSTITUTE OF f I \V\tf)) }) INSTITUUT VAN INTERNATIONAL ^^J£g^ INTERNASIONALE AFFAIRS ^*^~~ AANGELEENTHEDE SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES NO 3 RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani ISBN NO.: 0-908371-88-8 February 1991 Toe South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 POUTICS IN AFRICA'S NEWEST STATE 2 National Reconciliation 2 Nation Building 4 Labour in Namibia 6 Education 8 The Local State 8 The Judiciary 9 Broadcasting 10 THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALM - AN UNBALANCED INHERITANCE 12 Mining 18 Energy 19 Construction 19 Fisheries 20 Agriculture and Land 22 Foreign Exchange 23 FOREIGN RELATIONS - NAMIBIA AND THE WORLD 24 CONCLUSIONS 35 REFERENCES 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ANNEXURES I - 5 and MAP 44 INTRODUCTION Namibia's accession to independence on 21 March 1990 was an uplifting event, not only for the people of that country, but for the Southern African region as a whole. Independence brought to an end one of the most intractable and wasteful conflicts in the region. With independence, the people of Namibia not only gained political freedom, but set out on the challenging task of building a nation and defining their relations with the world. From the perspective of mediation, the role of the international community in bringing about Namibia's independence in general, and that of the United Nations in particular, was of a deep structural nature. -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

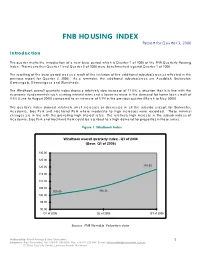

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

Namibia a Violation of Trust

AN OXFAM REPORT ON INTERNATIONAL RESPONSIBILITY FOR POVERTY IN NAMIBIA M Y First Published 1986 ©Oxfam 1986 ISBN 0 85598 0761 Printed in Great Britain by Express Litho Service (Oxford) Published by Oxfam 274 Banbury Road Oxford 0X2 7DZ United Kingdom This book converted to digital file in 2010 Acknowledgements My main thanks must go to all the Namibian people who generously gave their time and expertise to help with the research for this book, particularly Oxfam friends and partners. I am also grateful to the Overseas Development Administration, the Foreign & Commonwealth Office, the Catholic Institute for International Relations and the Namibian Support Committee for their assistance in providing information. Thanks are especially due for the time and advice given by all those who read and commented on the drafts. In particular, I am grateful to Richard Moorsom who helped with both research and editing, and to Justin Ellis, Julio Faundez, Peter Katjavivi, Prudence Smith, Paul Spray and Brian Wood. This book reflects the collective experience of Oxfam's work in Namibia over the past twenty-two years and I have therefore relied on the active collaboration of Oxfam staff and trustees. Sue Coxhead deserves special thanks for her help with research and typing. Finally, without the special help with childcare given by Mandy Bristow, Caroline Lovick and Prudence Smith, the book would never have seen the light of day. Susanna Smith March 1986 ANGOLA A M B I A 3*S^_5 Okavango Si Swamp .or Map 1: Namibia and its neighbours Map 2: Namibia B OTSWANA frontiers restricted areas 'homelands' tar roads AT LANTIC «~ other roads OCEAN railways rivers Luderi I capital city A main towns A mines: 1 TSUMEB copper/lead 2 ROSSING uranium 3 ORANJEMUNO diamonds Oranjemu Scale: 100 200 miles AFRICA Adapted from The Namibians, the Minority Rights Group report no. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith.