Windhoek, Namibia Casenote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

The German Colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German Rivalry, 1883-1915

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1995 Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915 Matthew Erin Plowman University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Plowman, Matthew Erin, "Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915" (1995). Student Work. 435. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOORS LEFT OPEN THEN SLAMMED SHUT: THE GERMAN COLONIZATION OF SOUTHWEST AFRICA AND THE ANGLO-GERMAN RIVALRY, 1883-1915. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by Matthew Erin Plowman July 1995 UMI Number: EP73073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Blsaartalibn Publish*rig UMI EP73073 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

Title: Walvis Bay Baseline Study *By: Priscilla Rowswell and Lucinda Fairhurst *Report Type: Research Study, *Date: February 2011

ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – Africa Walvis Bay Baseline Study *Title: Walvis Bay Baseline Study *By: Priscilla Rowswell and Lucinda Fairhurst *Report Type: Research Study, *Date: February 2011 *IDRC Project Number-Component Number: 105868-001 *IDRC Project Title: Sub-Saharan African Cities: A Five-City Network to Pioneer Climate Adaptation through Participatory Research and Local Action. *Country/Region: Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique, Tanzania, Mauritius *Full Name of Research Institution: ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability - Africa *Address of Research Institution: P.O. Box 5319, Tygervalley, 7536, Cape Town, South Africa *Name(s) of ICLEI Africa Core Project Team: Lucinda Fairhurst and Priscilla Rowswell *Contact Information of Researcher/Research Team members: [email protected]; +27 21 487 2312 *This report is presented as received from project recipient(s). It has not been subjected to peer review or other review processes. *This work is used with the permission of ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability - Africa *Copyright: 2012, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability - Africa *Abstract: This project addresses knowledge, resource, capacity and networking gaps on the theme: 'Strengthening urban governments in planning adaptation.' The main objective of this project is to develop an adaptation framework for managing the increased risk to African local government and their communities due to climate change impact. The ultimate beneficiaries of this project will be African local governments and their communities. The guiding and well-tested ICLEI principle of locally designed and owned projects for the global common good, specifically in a developing world context, will be applied throughout project design, inception and delivery. Additionally, the research will test the theory that the most vulnerable living and working in different geographical, climatic and ecosystem zones will be impacted differently and as such, will require a different set of actions to be taken. -

Namibia Starline Timetable

TRAIN : WINDHOEK – GOBABIS – WINDHOEK TRAIN : WINDHOEK – OTJIWARONGO – WINDHOEK TRAIN NO 9903 TRAIN NO 9904 TRAIN NO 9966 TRAIN NO 9915 TIMETABLE DAYS MON, DAYS MON, MONDAYS MONDAY WED, FRI WED, FRI WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS Windhoek D 05:50 Gobabis D 14:50 Windhoek D 15:45 Otjiwarongo D 15:40 Hoffnung D 06:55 Witvlei D 16:14 Okahandja A 18:00 Omaruru A 18:30 Neudamm D 07:35 Omitara A 17:52 D 18:05 D 19:30 Omitara A 10:10 D 17:56 Karibib D 20:40 Kranzberg A 21:10 D 10:12 Neudamm D 20:36 Kranzberg A 21:20 D 21:50 Witvlei D 11:53 Hoffnung D 21:18 D 21:40 Karibib D 22:20 Gobabis A 13:25 Windhoek A 22:25 Omaruru A 23:00 Okahandja A 01:30 D 23:35 D 01:40 Otjiwarongo A 02:20 Windhoek A 03:20 TRAIN : WINDHOEK – WALVIS BAY – WINDHOEK TRAIN: WALVIS BAY–OTJIWARONGO–WALVIS BAY EFFECTIVE FROM TRAIN NO 9908 TRAIN NO 9909 TRAIN NO 9901 / 9912 TRAIN NO 9907 / 9900 DAYS DAILY DAYS DAILY MONDAY MONDAY MONDAY 21 JANUARY 2008 EXCEPT EXCEPT WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY SAT SAT FRIDAY FRIDAY STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS Business Hours : Windhoek Central Reservations : Monday – Friday 07:00 to 19:00 Tel. (061) 298 2032/2175 Windhoek D 19:55 Walvis Bay D 19:00 Otjiwarongo D 14:40 Walvis Bay D 14:20 Saturdays 07:00 to 09:30 Fax (061) 298 2495 Okahandja A 21:55 Kuiseb D 19:20 Omaruru A 17:30 Kuiseb D 14:30 Sundays 15:30 to 19:00 D 22:05 Swakopmund A 20:35 D 18:30 Swakopmund A 15:50 Website : www.transnamib.com.na Karibib D 00:40 D 20:45 Kranzberg A 19:55 D 16:00 StarLine Information : E-mail : [email protected] Kranzberg -

Namibia After 26 Years

On the other side of the picture are elements in the police and to devote their energies instead to making the force who are not neutral, or are trigger-happy, or are country ungovernable. Such lessons are more easily both. They may well be covert rightwingers trying to learnt than forgotten. Ungovernability down there, where sabotage reform. Other rightwingers seem set on making the necklace lies in wait for non-conformists, and the the mining town of Welkom a no-go area for Blacks. They incentive to learn has been largely lost, presents the ANC may not stop there. with a major problem. For Mr De Klerk it certainly makes his task of persuading Whites to accept a future in a non- More disturbing than any of this has been the resurrection racial democracy a thousand times more difficult. of the dreaded "necklace", surely one of the most despicable and dehumanising methods over conceived So what has to be done if what is threatening to become a for dealing with people you think might not be on your lost generation is to be saved, and if something like the side. The leaders of the liberation movement who failed, Namibian miracle is to be made to happen here? for whatever reason, to put a stop to this ghastly practice when it first reared its head amongst their supporters all People need to be given something they feel is important those years ago, may well live to rue that day. Only and constructive to do. What better than building a new Desmond Tutu and a few other brave individuals ever society? risked their own lives to stop it. -

S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH

UNITED NATIO Distr . GENERA1 S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 5 AUGTJST 1968 FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL FOR NAMIBIA ADDRESSED TO 'THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to bring to your attention a message received by the Secretary-General from Mr, Clemens Kapuuo of Windhoek, Namibia, on 24 July lsi'48, stating that non-white Namibians were being forcibly removed from their homes in Windhoek to the new segregated area of Katutura, and requesting the Secretary- General to convene a meeting of the Security Council to consider the matter. According to the message, the deadline for their removal is 31 August 1968, after which date they would not be allowed to continue to live in their present areas of residence. On the same date the Secretary-General transmitted the message in a letter to the United Nations Council for Namibia as he felt that the Council might wish to give the matter urgent attention. A copy of the letter is attached herewith (annex I). The Council considered the matter at its 34th and 35th meetings, held on 25 July 1968 and 5 August 1968 respectively. According to information available to the Council (annex II), the question of the removal of non-whites from their homes in Windhoek to the segregated area 0-P IChtutura first arose in 1959 and was the subject of General Assembly resolution 1567 (XV) of 18 December 1960. At the aforementioned meetings, the Council concluded that the recent actions of the South African Government constitute further evidence of South Africa's continuing defiance of the authority of the United Nations and a further violation of General Assembly resolutions 2145 (XXI), 2248 (S-V), 2325 (XXII) and 2372 (XXII). -

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek Final - Main Report 1 Master Plan of City of Windhoek including Rehoboth, Okahandja and Hosea Kutako International Airport The responsibility of the project and its implementation lies with the Ministry of Works and Transport and the City of Windhoek Project Team: 1. Ministry of Works and Transport Cedric Limbo Consultancy services provided by Angeline Simana- Paulo Damien Mabengo Chris Fikunawa 2. City of Windhoek Ludwig Narib George Mujiwa Mayumbelo Clarence Rupingena Browny Mutrifa Horst Lisse Adam Eiseb 3. Polytechnic of Namibia 4. GIZ in consortium with Prof. Dr. Heinrich Semar Frederik Strompen Gregor Schmorl Immanuel Shipanga 5. Consulting Team Dipl.-Volksw. Angelika Zwicky Dr. Kenneth Odero Dr. Niklas Sieber James Scheepers Jaco de Vries Adri van de Wetering Dr. Carsten Schürmann, Prof. Dr. Werner Rothengatter Roloef Wittink Dipl.-Ing. Olaf Scholtz-Knobloch Dr. Carsten Simonis Editors: Fatima Heidersbach, Frederik Strompen Contact: Cedric Limbo Ministry of Works and Transport Head Office Building 6719 Bell St Snyman Circle Windhoek Clarence Rupingena City of Windhoek Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P.O Box 8016 Windhoek,Namibia, www.sutp.org Cover photo: F Strompen, Young Designers Advertising Layout: Frederik Strompen Windhoek, 15/05/2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 1.1. Purpose ........................................................................................................................................ -

Withholding Tax on Services Rendered by a Non-Resident

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA INLAND REVENUE MINISTRY OF FINANCE REGISTRATION AS TAXPAYER (WTS) APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION - WITHHOLDING TAX ON SERVICES RENDERED BY A NON-RESIDENT MARK THIS BOX WITH AN X IF YOU OFFICE OF REGISTRATION MAKE USE OF NON-RESIDENT SERVICE PROVIDERS ON A REGULAR BASIS (COMPLETE BLOCKS IN BLACK INK. USE CAPITAL LETTERS, AND WHERE APPLICABLE, MARK WITH AN “X”) PART 1: BUSINESS/PERSONAL PARTICULARS REGISTERED/ TAXPAYER NAME TRADE NAME BUSINESS REG./ IDENTITY NO. DATE OF BIRTH BUSINESS/ RESIDENTIAL ADDRESS POSTAL ADDRESS CITIZENSHIP OCCUPATION NAME AND ADDRESS OF EMPLOYER MAGISTERIAL DISTRICT TAXPAYER FILE IDENTIFICATION NO. PART 2: TAXPAYER’S CONTACT DETAILS (NOT REPRESENTATIVE) WORK TELEPHONE NO. HOME TELEPHONE NO. FAX NO. CELLPHONE NO. EMAIL ADDRESS PART 3: BANKING DETAILS BANK BRANCH CODE ACCOUNT NO. ACCOUNT HOLDER TYPE OF ACCOUNT SAVINGS CURRENT TRANSMISSION OFFICIAL BANK STAMP I DECLARE THAT THE PARTICULARS PROVIDED ARE CORRECT. NAME CAPACITY SIGNATURE DATE REGIONAL OFFICES WINDHOEK OSHAKATI KEETMANSHOOP WALVIS BAY OTJIWARONGO RUNDU KATIMA MULILO Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Receiver of Revenue, Moltke St., Dr. Agostino Neto St.,Private Hampie Plichta Ave., Cnr. Sam Nujoma Ave. & Cnr. Dr. Libertine Amathila Markus Siwarongo St., Ngoma Rd., Boma, Private Bag 13185, Bag 5548, Private Bag 22151, 14th Rd., Ave. & Frans Indongo St. Private Bag 2117, Rundu Private Bag 1029, Windhoek Oshakati Keetmanshoop Private Bag 5027, Walvis Bay P.O. Box 2127, Otjiwarongo Tel.: (066) 265 030 Ngweze Tel.: (061) 209 2644/5 Tel.: (065) 229 728/9 Tel,: (063) 220 1000 Tel.: (064) 208 6073/4/5 Tel.: (067) 300 400 Fax: (066) 256 546 Tel,: (066) 252735/53 Fax: (061) 209 2001 Fax: (065) 221 190 Fax: (063) 244 863/222 041 Fax: (064) 208 6100 Fax: (067) 300 401 Fax: (066) 252777 THERE ARE SEVERE PENALTIES/INTEREST FOR FALSE DECLARATIONS, FAILURE TO PAY TAX WHEN DUE, OR SUBMITTING RETURNS LATE. -

471 Mari Ne Law Developments I N Namibia D. J. Devine Institute

Mari ne Law Developments i n Namibia D. J. Devine Institute of Marine Law, University of Cape Town, South Africa Introduction Namibia became an independent state on 21 March 1990. Though only three years have elapsed since independence, that period has witnessed a number of important legal developments in the marine sector. The Constitution of Namibia contains provisions which are important in a marine context. The legislature has been active, and four important Acts have been adopted. Finally, the High Court 2 of Namibia has given judgment in six marine law case. It is the intention of this article to describe these constitutional, legislative and judicial marine law developments. The topics covered include maritime zones and their borders, passage rights, ownership of marine resource, the fishery law applicable in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a new fisheries regime, forfeiture of vessels used in committing fishery offences, questions relating to third party rights in such vessels, and international co-operation in enforcing fishery laws. The Territory of the Republic of Namibia It is necessary at the outset to describe what the territory of Namibia is and also the former status of the constituent parts of that territory. The reason is that the distinction between the different parts of the territory now claimed by Namibia is relevant to some of the questions later discussed in this article. The Constitution of Namibia describes the national territory of Namibia as "including the enclave, harbour and port of Walvis Bay, as well as the off-shore islands of Namibia, and its southern boundary shall extend to the middle of the Orange river."3 1 Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone of Namibia Act 3 of 1990:Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone of Namibia Amendment Act 30 of 1991;Marine Traffic Amendment Act 15 of 1991;Sea Fisheries Act 29 of 1992. -

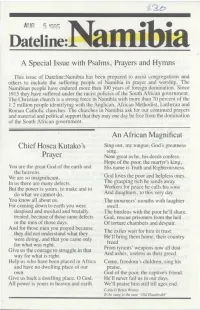

A Special Issue with Psalms, Prayers and Hymns Chief Hosea Kutako 'S

A Special Issue with Psalms, Prayers and Hymns This issue of Dateline:Namibia has been prepared to assist congregations and others to include the suffering people of Namibia in prayer and worship. The Namibian people have endured more than 100 years of foreign domination. Since 1915 they have suffered under the racist policies of the South African government. The Christian church is a strong force in Namibia with more than 70 percent of the 1.2 miUion people identifying with the Anglican. African Methodist. Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches. The churches in Namibia ask for our continued prayers and material and political support that they may one day be free from the domination of the South African government. An African Magnificat Chief Hosea Kutako 's Sing out. my tongue. God ·s greatness sing. Prayer None great a'i he, his deeds confess. Hope of the poor. the martyr's king. You are the great God of the earth and His name is Truth and Righteousness. the heavens. We are so insignificant. God loves the poor and helpless ones. In us there are many defects. The grasping rich he sends away. But the power is yours, to make and to Workers for peace he calls his sons do what we cannot do. And daughters, to this very day. You know all about us. The mourners' mouths with laughter For coming down to earth you were swell. despised and mocked and brutaUy The burdens with the poor he'll share. treated, because of those same defects God, rescue prisoners from the hell in the men of those days. -

Namibia & Botswana 2017

Namibia & Botswana 2017 A Tropical Birding Custom Trip 3-18 September 2017 Guides: Ken Behrens & Charley Hesse September 3-18, 2017 Guided by: Ken Behrens Charley Hesse Photos and Report by Ken Behrens www.tropicalbirding.com The Crimson-breasted Gonolek is Namibia’s national bird. WINDHOEK After arrival in Namibia’s capital, we had a day to relax and enjoy the excellent birding on offer around this small and charming city. Windhoek has a population of about 300,000, out of Namibia’s tiny population of only 2.1 million, remarkable for a country that is twice the size of California. Monteiro’s Hornbill (left), one of many Namibian near-endemic birds that we were seeking. On our morning walk at Avis Dam, we enjoyed Barred Wren-Warbler (top left) and Black-fronted or African Red-eyed Bulbul (bottom left), while there were a bounty of waterbirds at the Gammons Water Care (Sewage!) Works, including Red-knobbed Coot (middle left) and African Darter (right). From Windhoek, in the central mountains, we descended into the Namib Desert, where species like the Common Ostrich survive despite incredibly harsh conditions. Creatures of the Namib: South African Ground Squirrel (bottom right); Tractrac Chat (top right); and Rueppell’s Bustard (left). WALVIS BAY AND SWAKOPMUND The Namib dune fields hold Namibia’s sole political endemic bird, the Dune Lark. Walvis Bay itself is a mecca for waterbirds, including thousands of Lesser Flamingos (right-hand page). Spitzkoppe is Namibia’s most distinctive and iconic mountain. Our avian target at Spitzkoppe was the charismatic and scarce Herero Chat.