Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Windhoek, Namibia Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Windhoek, Namibia Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA NAMIBIA Population: 2,533,224 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 1.91% (2018) Median Age: 21.4 GDP: USD$29.6 billion (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita: USD$11,200 (2017 est.) City of Intervention: Windhoek Urban Population: 50% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.2% annual rate of change (2015- 2020 est.) Land Area: 910,768 sq km Total Roadways: 48,327 km (2014) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi-Scalar Governance Following a 25-year war, Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 under the rule of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Since then, SWAPO has held the presidency, prime minister’s office, the national assembly, and most local and regional councils by a large majority. While opposition parties are active (there are over ten groups), they remain weak and fragmented, with most significant political differences negotiated within SWAPO. The constitution and other legislation dating to the early 1990s emphasize the role of regional and local councils – and since 1998, the government has been engaged in efforts to support decentralization of power.1 However, all levels are connected by SWAPO (through common membership), so power remains effectively centralized. -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

Thesis Hum 2019 Brock Penoh

Politics of Reparations: Unravelling the Power Relations in the Herero/Nama Genocide Reparations Claims Penohole Brock, BRCPEN002 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fullfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy (Justice and Transformation). Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town [2019] University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 10.02.2019 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract The Herero/Nama Genocide (1904-1908) under German colonialism in Namibia is the first genocide of the twentieth century and has stirred debates around reparations for historical injustices. Reparative Justice has evolved into a victim-centric pillar of justice, in which perpetrators are legally and morally obligated to pay reparations in its several forms to its victims, including material and symbolic reparations. This thesis is a case study of reparations claims for historical injustices, specifically colonial genocide and explores such claims as a political process. -

RUMOURS of RAIN: NAMIBIA's POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre Du Pisani

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani THE .^-y^Vr^w DIE SOUTH AFRICAN i^W*nVv\\ SUID AFRIKAANSE INSTITUTE OF f I \V\tf)) }) INSTITUUT VAN INTERNATIONAL ^^J£g^ INTERNASIONALE AFFAIRS ^*^~~ AANGELEENTHEDE SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES NO 3 RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani ISBN NO.: 0-908371-88-8 February 1991 Toe South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 POUTICS IN AFRICA'S NEWEST STATE 2 National Reconciliation 2 Nation Building 4 Labour in Namibia 6 Education 8 The Local State 8 The Judiciary 9 Broadcasting 10 THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALM - AN UNBALANCED INHERITANCE 12 Mining 18 Energy 19 Construction 19 Fisheries 20 Agriculture and Land 22 Foreign Exchange 23 FOREIGN RELATIONS - NAMIBIA AND THE WORLD 24 CONCLUSIONS 35 REFERENCES 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ANNEXURES I - 5 and MAP 44 INTRODUCTION Namibia's accession to independence on 21 March 1990 was an uplifting event, not only for the people of that country, but for the Southern African region as a whole. Independence brought to an end one of the most intractable and wasteful conflicts in the region. With independence, the people of Namibia not only gained political freedom, but set out on the challenging task of building a nation and defining their relations with the world. From the perspective of mediation, the role of the international community in bringing about Namibia's independence in general, and that of the United Nations in particular, was of a deep structural nature. -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: Genocide and the Quest of Recompense Gewald, J.B.; Jones A

Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: genocide and the quest of recompense Gewald, J.B.; Jones A. Citation Gewald, J. B. (2004). Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: genocide and the quest of recompense. In Genocide, war crimes and the West: history and complicity (pp. 59-77). London: Zed Books. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4853 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4853 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Imperial Germany and the Herero of Southern Africa: Genocide and the Quest for Recompense Jan-Bart Gewald On 9 September 2001, the Herero People's Reparations Corporation lodged a claim in a civil court in the US District of Columbia. The claim was directed against the Federal Republic of Germany, in the person of the German foreign minister, Joschka Fischer, for crimes against humanity, slavery, forced labor, violations of international law, and genocide. Ninety-seven years earlier, on n January 1904, in a small and dusty town in central Namibia, the first genocide of the twentieth Century began with the eruption of the Herero—German war.' By the time hostilities ended, the majority of the Herero had been killed, driven off their land, robbed of their cattle, and banished to near-certain death in the sandy wastes of the Omaheke desert. The survivors, mostly women and children, were incarcerated in concentration camps and put to work as forced laborers (Gewald, 1995; 1999: 141—91). Throughout the twenti- eth Century, Herero survivors and their descendants have struggled to gain recognition and compensation for the crime committed against them. -

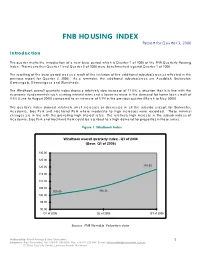

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006

FNB HOUSING INDEX Report for Quarter 3, 2006 Introduction This quarter marks the introduction of a new base period which is Quarter 1 of 2006 of the FNB Quarterly Housing Index. This means that Quarter 2 and Quarter 3 of 2006 were benchmarked against Quarter 1 of 2006. The resetting of the base period was as a result of the inclusion of five additional suburbs/areas as reflected in the previous report for Quarter 2, 2006. As a reminder, the additional suburbs/areas are Auasblick, Brakwater, Goreangab, Okuryangava and Wanaheda. The Windhoek overall quarterly index shows a relatively slow increase of 11.6%, a situation that is in line with the economic fundamentals such as rising interest rates and a lower increase in the demand for home loan credit of 3.6% (June to August 2006) compared to an increase of 5.9% in the previous quarter (March to May 2006). This quarter’s index showed relatively small increases or decreases in all the suburbs except for Brakwater, Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park where moderate to high increases were recorded. These minimal changes are in line with the prevailing high interest rates. The relatively high increase in the suburb indices of Academia, Eros Park and Hochland Park could be ascribed to a high demand for properties in these areas. Figure 1: Windhoek Index Windhoek overall quarterly index - Q3 of 2006 (Base: Q1 of 2006) 130.00 125.00 120.00 118.55 115.00 110.00 105.00 100.00 106.22 100.00 95.00 90.00 Q1 of 2006 Q2 of 2006 Q3 of 2006 Source: FNB Namibia Valuation data Authored by: Martin Mwinga & Alex Shimuafeni 1 Enquiries: Alex Shimuafeni, Tel: +264 61 2992890, Fax: +264 61 225 994, E-mail: [email protected] 5th Floor, First City Centre, Levinson Arcade, Windhoek Brakwater recorded an extraordinary high quarterly increase of 72% from Quarter 2. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia

THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA Wade Pendleton, Ndeyapo Nickanor and Akiser Pomuti Pendleton, W., Nickanor, N., & Pomuti, A. (2012). The State of Food Insecurity in Windhoek, Namibia. AFSUN Food Security Series, (14). AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 AFRICAN FOOD SECURITY URBAN NETWORK (AFSUN) THE STATE OF FOOD INSECURITY IN WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA WADE PENDLETON, NDEYAPO NICKANOR AND AKISER POMUTI SERIES EDITOR: PROF. JONATHAN CRUSH URBAN FOOD SECURITY SERIES NO. 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The financial support of the Canadian International Development Agency for AFSUN and this publication is acknowledged. Cover Photograph: Aaron Price, http://namibiaafricawwf.blogspot.com Published by African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN) © AFSUN 2012 ISBN 978-1-920597-01-6 First published 2012 Production by Bronwen Müller, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publisher. Authors Wade Pendleton is a Research Associate of the African Food Security Urban Network. Ndeyapo Nickanor is a Lecturer at the University of Namibia. Akiser Pomuti is Director of the University Central Consultancy Bureau at the University of Namibia. Previous Publications in the AFSUN Series No 1 The Invisible Crisis: Urban Food Security in Southern Africa No 2 The State of Urban Food Insecurity in Southern Africa No -

Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: a Mixed Methods Approach

CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT IN NAMIBIA: A MIXED METHODS APPROACH by MEREDITH JOY DEBOOM B.A., University of Iowa, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography 2013 This thesis entitled: Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach written by Meredith Joy DeBoom has been approved for the Department of Geography John O’Loughlin, Chair Joe Bryan, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Abstract DeBoom, Meredith Joy (M.A., Geography) Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach Thesis directed by Professor John O’Loughlin In May 2011, Namibia’s Minister of Mines and Energy issued a controversial new policy requiring that all future extraction licenses for “strategic” minerals be issued only to state-owned companies. The public debate over this policy reflects rising concerns in southern Africa over who should benefit from globally-significant resources. The goal of this thesis is to apply a critical geopolitics approach to create space for the consideration of Namibian perspectives on this topic, rather than relying on Western geopolitical and political discourses. Using a mixed methods approach, I analyze Namibians’ opinions on foreign involvement, particularly involvement in natural resource extraction, from three sources: China, South Africa, and the United States.