Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Unimagined. Unexpected. Unexplored

Unimagined. Unexpected. Unexplored. OFFERING AN UNEXPECTED, OTHER- WORLDLY EXPERIENCE BOTH IN ITS LANDSCAPE AND THE REWARDS IT BRINGS TO TRAVELLERS, THE ARID EDEN ROUTE STRETCHES FROM SWAKOPMUND IN THE SOUTH TO THE ANGOLAN BORDER IN THE NORTH. THE ROUTE INCLUDES THE PREVIOUSLY RESTRICTED WESTERN AREA OF ETOSHA NATIONAL PARK, ONE OF NAMIBIA’S MOST IMPORTANT TOURIST DESTINATIONS WITH ALMOST ALL VISITORS TO THE COUNTRY INCLUDING THE PARK IN THEIR TRAVEL PLANS. The Arid Eden Route also includes well-known tourist attractions such as Spitzkoppe, Brandberg, Twyfelfontein and Epupa Falls. Travellers can experience the majesty of free-roaming animals, extreme landscapes, rich cultural heritage and breathtaking geological formations. As one of the last remaining wildernesses, the Arid Eden Route is remote yet accessible. DID YOU KNOW? TOP reasons to VISIT... “Epupa” is a Herero word for “foam”, in reference to the foam created by the falling water. Visit ancient riverbeds, In the Himba culture a sign of wealth is not the beauty or quality of a tombstone, craters and a petrified but rather the cattle you had owned during your lifetime, represented by the horns forest on your way to an on your grave. oasis in the desert – the Epupa Waterfall The desert-adapted elephants of the Kunene region rely on as little as nine species of plants for their survival while in Etosha they utilise over 80 species. At 2574m, Königstein is Namibia’s highest peak and is situated in the Brandberg Mountains. The Brandberg is home to over 1,000 San paintings, including the famous White Lady which dates back 2,000 years. -

Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W

T 0 ~ume ~-723X)Southern i\fric-a 7, Japuary-wruarv 1997 Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W. Congress Parkway, Chicago, IL 60624 phone (773) 826-4481 fax (773) 533-4728 TEARS, FEARS, AND HOPES: Healing the Memories in South Africa Pastor Philip Knutson of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, reports on a workshop he and other church leaders attended. "The farmer tied my grandfather up to a pole and told him he must get rid of all his cattle.. .! was just a boy then but I will never forget that.. .! could have been a wealthy farmer today if our fam ily had not been dispossessed in that way." The tears streamed down his face as this "coloured" pastor related his most painful experience of the past to a group at a workshop entitled "Exploring Church Unity Within the Context of Healing and Reconciliation" held in Port Elizabeth recently. A black Methodist pastor related his feelings of anger and loss at being deprived of a proper education. Once while holding a service to commemorate the young martyrs ofthe June 1976 Uprising, his con gregation was attacked and assaulted in the church. What hurt most, he said, was that the attacking security forces were black. The workshop, sponsored by the Provincial Council of Churches, was led by Fr. Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest who lost both hands and an eye in a parcel bomb attack in Harare in 1990. In his new book Partisan and Priest and in his presenta tion he said that every South African has three stories to tell. -

Randi-Markusen-Botsw

The Baherero of Botswana and a Legacy of Genocide Randi Markusen Member, Board of Directors World Without Genocide The Republic of Botswana is an African success story. It emerged in 1966 as a stable, multi-ethnic, democracy after eighty-one years as Bechuanaland, a British Protectorate. It was a model for progress, unlike many of its neighbors. Scholars from around the globe were eager to study and chronicle its people and formation. They hoped to learn what made it the exception, and so different from the rest of the continent.1 Investigations most often focused on two groups, the San, who were indigenous hunter-gathers, and the Tswana, the country’s largest ethnic group. But the scholars neglected other groups in their research. The Herero, who came to Botswana from Namibia in the early 1900s, long before independence, found themselves in that neglected category and were often unmentioned, even though their contributions were rich and their experiences compelling.2 The key to understanding the Herero in Botswana today lies in their past. A Short History of the Herero People The Herero have lived in the Southwest region of Africa for hundreds of years. They are believed to be descendants of pastoral migrants from Central Africa who made their way southwest during the 17th century and eventually inhabited what is now northern Namibia. In the middle of the 19th century they expanded farther south, seeking additional grassland for their cattle. This encroachment created conflicts with earlier migrants and indigenous groups. As a result, the Herero were engaged in on-and- off inter-tribal wars. -

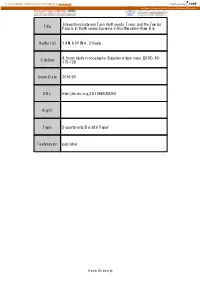

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Threatened Pastures

Himba of Namibia and Angola Threatened pastures ‘All the Himba were born here, next to the river. When the Himba culture is flourishing and distinctive. All Himba cows drink this water they become fat, much more than if are linked by a system of clans. Each person belongs to they drink any other water. The green grass will always two separate clans; the eanda, which is inherited though grow, near the river. Beside the river grow tall trees, and the mother, and the oruzo, which is inherited through the vegetables that we eat. This is how the river feeds us. father. The two serve different purposes; inheritance of This is the work of the river.’ cattle and other movable wealth goes through the Headman Hikuminue Kapika mother’s line, while dwelling place and religious authority go from father to son. The Himba believe in a A self-sufficient people creator God, and to pray to him they ask the help of their The 15,000 Himba people have their home in the ancestors’ spirits. It is the duty of the male head of the borderlands of Namibia and Angola. The country of the oruzo to pray for the welfare of his clan; he prays beside Namibian Himba is Kaoko or Kaokoland, a hot and arid the okuruwo, or sacred fire. Most important events region of 50,000 square kilometres. To the east, rugged involve the okuruwo; even the first drink of milk in the mountains fringe the interior plateau falling toward morning must be preceded by a ritual around the fire. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

Syllabuses History Feb2010.Pdf

Republic of Namibia MINISTRY OF EDUCATION JUNIOR SECONDARY PHASE HISTORY SYLLABUS GRADES 8 - 10 2010 Ministry of Education National Institute for Educational Development (NIED) Private Bag 2034 Okahandja Namibia © Copyright NIED, Ministry of Education, 2010 History Syllabus Grades 8 - 10 ISBN: 99916-48-22-4 Printed by NIED www.nied.edu.na Publication date: January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2. RATIONALE AND AIMS ................................................................................................... 1 3. BASIC COMPETENCIES AND LEARNING OUTCOMES ............................................. 1 5. GENDER ISSUES ................................................................................................................ 2 6. LOCAL CONTEXT AND CONTENT ................................................................................ 2 7. LINKS TO OTHER SUBJECTS AND CROSS-CURRICULAR ISSUES ......................... 2 8. APPROACH TO TEACHING AND LEARNING .............................................................. 7 9. SUMMARY OF LEARNING CONTENT .......................................................................... 8 10. LEARNING CONTENT ...................................................................................................... 9 10.1 LEARNING CONTENT FOR GRADE 8 ................................................................. 9 10.2 LEARNING CONTENT FOR GRADE 9 .............................................................. -

Aus Dem Zentrum Für Innere Medizin Bereich Endokrinologie & Diabetologie Leiter: Professor Dr

Aus dem Zentrum für Innere Medizin Bereich Endokrinologie & Diabetologie Leiter: Professor Dr. med. Dr. phil. Peter Herbert Kann des Fachbereichs Medizin der Philipps-Universität Marburg The change of lifestyle in an indigenous Namibian population group (Ovahimba) is associated with alterations of glucose metabolism, metabolic parameters, cortisol homeostasis and parameters of bone quality (quantitative ultrasound). Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der gesamten Humanmedizin dem Fachbereich Medizin der Philipps-Universität Marburg vorgelegt von Anneke M. Wilhelm geb. Voigts aus Windhoek/Namibia Marburg, 2014 II Angenommen vom Fachbereich der Medizin der Philipps-Universität Marburg am: 10. Juli 2014 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs. Dekan: Herr Prof. Dr. H. Schäfer Referent: Herr Prof. Dr. Dr. Peter Herbert Kann 1. Koreferent: Herr Prof. Dr. P. Hadji III IV to Martin and to my parents for their faith in me V VI Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................. VII GENERAL INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................. 3 PART A THEORETICAL BACKGROUND .......................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1 DIABETES ......................................................................................... 6 1. Definition, Classification, Treatment -

Josephine Ntelamo Sitwala Master of Arts

LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE IN THE MALOZI COMMUNITY OF CAPRIVI Josephine Ntelamo Sitwala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the subject SOCIOLINGUISTICS at the University of South Africa Supervisor: Prof L.A. Barnes February 2010 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. vi Abstract ............................................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 ................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction: Statement of the problem ...................................................................... 1 1.2 Aim of the study .......................................................................................................... 1 1.3 The research questions ................................................................................................ 2 1.4 The hypothesis of the study ......................................................................................... 2 1.5 Significance of the study ............................................................................................. 3 1.6 Motivation for the study .............................................................................................. 3 1.7 The Malozi and their language .................................................................................... 4 -

Customary and Legislative Aspects of Land Registration and Management on Communal Land in Namibia

Communal land in Namibia: a free for all Customary and legislative aspects of land registration and management on communal land in Namibia John Mendelsohn (RAISON – Research & Information Services of Namibia) December 2008 Report prepared for the Ministry of Land & Resettlement and the Rural Poverty Reduction Programme of the European Union Contents Summary_________________________________________________________3 Abbreviations and definitions_________________________________________5 Acknowledgements_________________________________________________5 Introduction_______________________________________________________6 Methods__________________________________________________________7 Functioning and structure of traditional authorities ________________________9 Recommendations___________________________________________14 Customary land registration _________________________________________14 Misunderstandings, confusions and objections_____________________15 Focus on higher levels of traditional authority ____________________17 Other aspects_______________________________________________18 Recommendations___________________________________________19 The management of communal land___________________________________22 Access to land ______________________________________________22 Inheritance_________________________________________________23 Commonages_______________________________________________25 The capture of land values by the elite ___________________________26 Recommendations___________________________________________29 APPENDICES -

13 Understanding Damara / ‡Nūkhoen and ||Ubun Indigeneity

13 • Understanding Damara / ‡Nūkhoen and ||Ubun indigeneity and marginalisation in Namibia Sian Sullivan and Welhemina Suro Ganuses1 • 1 Introduction In historical and ethnographic texts for Namibia, Damara / ‡N khoen peoples are usually understood to be amongst the territory’s “oldest” or “original” inhabitants.2 Similarly, histories written or narrated by Damara / ‡N khoen peoples include their self-identification as original inhabitants of large swathes of Namibia’s 1 Contribution statement: Sian Sullivan has drafted the text of this chapter and carried out the literature review, with all field research and Khoekhoegowab-English translations and interpretations being carried out with Welhemina Suro Ganuses from Sesfontein / !Nani|aus. We have worked together on and off since meeting in 1994. The authors’ stipend for this work is being directed to support the Future Pasts Trust, currently being established with local trustees to support heritage activities in Sesfontein / !Nani|aus and surrounding areas, particularly by the Hoanib Cultural Group (see https://www.futurepasts.net/future-pasts-trust). 2 See, for example, Goldblatt, Isaak, South West Africa From the Beginning of the 19th Century, Juta & Co. Ltd, Cape Town, 1971; Lau, Brigitte, A Critique of the Historical Sources and Historiography Relating to the ‘Damaras’ in Precolonial Namibia, BA History Dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, 1979; Fuller, Ben, Institutional Appropriation and Social Change Among Agropastoralists in Central Namibia 1916–1988, PhD Dissertation,