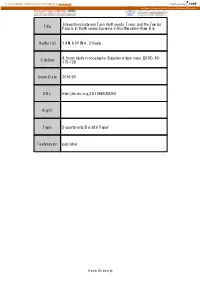

German Reparations to the Herero Nation: an Assertion of Herero Nationhood in the Path of Namibian Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

IPPR Briefing Paper NO 44 Political Party Life in Namibia

Institute for Public Policy Research Political Party Life in Namibia: Dominant Party with Democratic Consolidation * Briefing Paper No. 44, February 2009 By André du Pisani and William A. Lindeke Abstract This paper assesses the established dominant-party system in Namibia since independence. Despite the proliferation of parties and changes in personalities at the top, three features have structured this system: 1) the extended independence honeymoon that benefits and is sustained by the ruling SWAPO Party of Namibia, 2) the relatively effective governance of Namibia by the ruling party, and 3) the policy choices and political behaviours of both the ruling and opposition politicians. The paper was funded in part by the Danish government through Wits University in an as yet unpublished form. This version will soon be published by Praeger Publishers in the USA under Series Editor Kay Lawson. “...an emergent literature on African party systems points to low levels of party institutionalization, high levels of electoral volatility, and the revival of dominant parties.” 1 Introduction Political reform, democracy, and governance are centre stage in Africa at present. African analysts frequently point to the foreign nature of modern party systems compared to the pre-colonial political cultures that partially survive in the traditional arenas especially of rural politics. However, over the past two decades multi-party elections became the clarion call by civil society (not to mention international forces) for the reintroduction of democratic political systems. This reinvigoration of reform peaked just as Namibia gained its independence under provisions of the UN Security Council Resolution 435 (1978) and the supervision of the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG). -

Washington, D.C

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIVIL DIVISION THE HERERO PEOPLE’S REPARATIONS CORPORATION, : a District of Columbia Corporation : 1625 K Street, NW, #102 : Washington, D.C. 20006 : : THE HEREROS, : a Tribe and Ethnic and Racial Group, : by and through its Paramount Chief : By Paramount Chief Riruako : Paramount Chief K. Riruako : P.O. Box 60991 Katutura : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Mburumba Getzen Kerina : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Kurundiro Kapuuo : Case No. 01-0004447 Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Judge Jackson Calendar 2 Cornelia Tjaveondja : Next Scheduled Event: P.O. Box 24861 : Initial Scheduling Conference Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : September 18, 2001 at 9:30 a.m. Moses Nguarambuka : P.O. Box 24861 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Hilde Kazakoka Kamberipa : SQ66 Genesis Street : P.O. Box 61831 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Festus Korukuve : P.O. Box 50 : Opuuo (Otuzemba), Namibia : Uezuvanjo Tjihavgc : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Ujeuetu Tjihange : Box 27 : Opuuo, Namibia : Moses Katuuo : P.O. Box 930 : Gobabis, Namibia 9000 : Levy K. O. Nganjone : P.O. Box 309 : Gobabis, Namibia : Festus Ndjai : Opuuo, Namibia : Hoomajo Jjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Uelembuia Tjinawba : Okandombo : Okunene Region, Namibia : Jararaihe Tjingee : Opuuo, Namibia : Hangekaoua Mbinge : Opuuo, Namibia : Ehrens Jeja : Box 210 : Omaruru : Omatjete, Namibia : Nathanael Uakumbua : Box 211 : Omaruru, Namibia : Rudolph Kauzuu : Box 210 : Omatjete : Omaruru, Namibia : 2 Jaendekua Kapika : Opuuo, Namibia : Ben Mbeuserua : P.O. Box 224 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Felix Kokati : Box 47 : Okakarara, Namibia 9000 : Samuel Upendura : Oyinene : Omaheke Region, Namibia : Majoor Festus Kamburona : P.O. 1131 : Windhoek, Republic of Namibia 9000 : Uetavera Tjirambi : Okonmgo : Okanene Region, Namibia : Julius Katjingisiua : P.O. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Randi-Markusen-Botsw

The Baherero of Botswana and a Legacy of Genocide Randi Markusen Member, Board of Directors World Without Genocide The Republic of Botswana is an African success story. It emerged in 1966 as a stable, multi-ethnic, democracy after eighty-one years as Bechuanaland, a British Protectorate. It was a model for progress, unlike many of its neighbors. Scholars from around the globe were eager to study and chronicle its people and formation. They hoped to learn what made it the exception, and so different from the rest of the continent.1 Investigations most often focused on two groups, the San, who were indigenous hunter-gathers, and the Tswana, the country’s largest ethnic group. But the scholars neglected other groups in their research. The Herero, who came to Botswana from Namibia in the early 1900s, long before independence, found themselves in that neglected category and were often unmentioned, even though their contributions were rich and their experiences compelling.2 The key to understanding the Herero in Botswana today lies in their past. A Short History of the Herero People The Herero have lived in the Southwest region of Africa for hundreds of years. They are believed to be descendants of pastoral migrants from Central Africa who made their way southwest during the 17th century and eventually inhabited what is now northern Namibia. In the middle of the 19th century they expanded farther south, seeking additional grassland for their cattle. This encroachment created conflicts with earlier migrants and indigenous groups. As a result, the Herero were engaged in on-and- off inter-tribal wars. -

Ufahamu: a Journal of African Studies

UCLA Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies Title Directory: African Liberation Movements and Support Groups Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/85p33873 Journal Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 3(2) ISSN 0041-5715 Author Berman, Sanford Publication Date 1972 DOI 10.5070/F732016403 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California -171- DII{CfORY: AFRICAN LIBERATIOO r1MltNTS AND SIFffiRT ---GIUPS*· by Sanford Berman (Ed. Note: Both this Directory and the Spring 1972 Bib Ziogrc:q;hy, "African Liberation Movements 11 (Vo Z. III, No. 1) will be regularly updated by the compiler in future issues. Additions and corrections should be directed to the Compiler, c/o UFAHAMU.) AFRICAN LIBERATIOO fiMI'fNTS Frente Nacional de Libertacao de Angola (FNLA/Angolan National -Liberation Front)§ ·- Founded in 1962 by merger of Uniao dos Populacoes de Angola (UPA) and Partido Democratico Angolano (PDA). Established Governo Revolucionario de Angola no Exilio (GRAE/Angolan Revolutionary Government in Exile) 1962. Leader and GRAE Premier: Holden Roberto. Zaire Republic: Ministere de l'Information, Planet Economie, G.R.A.E., B.P. 1320, Kinshasa. Organ: Actualites (no. 3 dated March 1971). §[Recognized by the O.A.U.] *Dates in parentheses f ollowing periodical titles repre sent first year of pubZication. The abbreviation "AIP" indicates that a full list of material may be found in the 2nd ed. of Alternatives in Print (Columbus, Ohio: Office of Educational Services, Ohio State University Libraries, 1972). -172- Movimento _PopuZar de Libertaaao de AngoZa (MPLA/PeopZe's Movement for the Liberation of AngoZa/Mouvement PopuZaire pour Za Liberation de Z'AngoZa)§ - Founded 10 Dec. -

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

Botswana's Role in the Namibian

Journal of Namibian Studies, 14 (2013): 127 – 130 ISSN 2197-5523 (online) Review: Johann Alexander Müller, “The struggle. It is unfortunate, however, that Inevitable Pipeline into Exile.” Botswana’s he did not draw upon Parsons’ pioneer- Role in the Namibian Liberation Struggle, ing article for a broader, regional Basel, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, picture of the inflow of political refugees 2012. into Botswana and what happened to them there. And Müller’s early chapters perhaps set the scene too broadly, When introducing a set of papers on introducing too much general context. Botswana and the liberation of Southern The first chapter includes a section on Africa some years ago, this reviewer theory that many readers will probably pointed out that, though valuable, they skip over. said little about how Botswana provided political, diplomatic, material and moral While Botswana was the major east/west support to the liberation movements in ‘pipeline’ into exile for Namibians from South Africa-occupied Namibia. In one the late 1950s to the mid 1970s, of the papers Neil Parsons wrote about Müller’s book, as his subtitle suggests, the south/north ‘pipeline’ – the term is goes beyond the way in which found in official documents of the early Namibians travelled through the country 1960s – through Botswana, used most to go elsewhere. The first work to dis- famously by Nelson Mandela, under the cuss in depth the liberation struggle in Setswana alias of David Motsamayi, in Namibia in relation to Botswana, his 1962. While Parsons mentioned that -

NAM \ BIAN Ll BE RATION

NAM \ BIAN Ll BE RATION: 5EL~· D£/FRM!NATIO ~ LAW MD POLITICS ELIZA8ET~ S. LANDIS EPISCOPAL CHUR&liMEN for SOUTH Room 1005 • 853 Broadway, New York, N. Y. 10003 • Phone: (212) 477·0066 -For A Free S1111tbem Alritll- NOVEMBER 1982 NAMIBIAN LIBERATION Independence for Namibia is one of the forenost issues of today's world that cries for solution. The Namibian people have been subjected to bru tal foreign rule and their land exploited by co lonial powers for a century. Their thrust for freedom has intensified since 1966 when SWAPO launched its armed struggle against the illegal South African occupiers of its country. Their cause has been on the agendas of the League of Nations and the United Nations for m:>re than six decades . NCM, after five-and-a-half years of 'delicate negotiations 1 managed by five Western powers , Namibia is no nearer independence. Pretoria is m:>re repressively in oontrol of the Terri torY and uses it as a staging ground for its militarY encroaclunents into Angola and as a fulcrum for its attempt to reverse the tide of liberation in Southern Africa. Yet the talks conducted by the Western Contact Group are dragged on, with the United States gov ernment insisting that Angola denude itself of its CUban allies as a pre-condition for a 1 Namibian settlement" . There is widespread confusion on just where the matter of Namibia stands. This report is designed to penetrate the tangle. This clear, succinct and timely analysis of the Namibian issue by Elizabeth S. landis comes out of the author's yearn of work in the African field and her dedication to the cause of freedom in Southern Africa.