The Maternal Genetic History of the Angolan Namib Desert: a Key Region For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Historische und ethnographische Betrachtungen der Sprachenpolitik Namibias Verfasser Reinhard Mayerhofer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 328 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Allgem./Angew. Sprachwissenschaft Betreuer: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rudolf de Cillia Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagungen 5 Einleitung 7 1. Linguistik und Kolonialismus 1.1. Linguistische Prozesse der Kolonisierung 1.1.1. Die Vorgeschichte des Kolonialismus 11 1.1.2. Der Prozess der Kolonisierung 13 1.1.3. Die Folgen der Kolonisierung 16 1.2. Identität – Kultur – Ideologie 19 1.3. Europäischer und afrikanischer Kulturbegriff 21 2. Methoden 2.1. Einleitung 26 2.2. Sprachenportraits 28 2.3. Das narrativ-biographische Interview 2.3.1. Interviewführung 30 2.3.2. Auswertung 31 2.4. Ethnographie des Sprachwechsels 32 2.5. Methodisches Resümee 34 3. Historische Betrachtungen I: Geschichte Namibias 37 3.1. Das staatslose Namibia 3.1.1. Frühe Geschichte 39 3.1.2. Missionen 43 3.2. Kolonisierung durch das deutsche Kaiserreich (1884-1915) 3.2.1. Bildung „Deutsch-Südwestafrikas“ 46 3.2.2. Hochphase der deutschen Kolonisierung 50 3.3. Erster und Zweiter Weltkrieg 53 3.4. Apartheid 56 3.4.1. Bantu-Education: Das Bildungssystem der Apartheid 57 3.4.2. Bewaffneter Widerstand, UNO-Sanktionen und Unabhängigkeit 63 3.5. Die ersten Jahre der Unabhängigkeit (1990-2000) 67 4. Historische Betrachtungen II: Sprachenpolitik in Namibia 4.1. Koloniale Sprachenpolitik 71 4.2. Postkoloniale Sprachenpolitik 77 3 5. Ethnographische Betrachtungen: Jüngste Entwicklungen und aktuelle Situation 5.1. Biographische Analyse 5.1.1. Überblick: Sprachverteilung in den Portraits 84 5.1.2. -

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

The History of Modern Rwanda Through Photos

The History of Modern Rwanda through Photos PHOTO LINKS WITH HISTORICAL DESCRIPTIONS DIRECTIONS: The photo URLs and accompanying historical descriptions listed below are the basis for the photo/ time line activity in The History of Modern Rwanda through Photos lesson plan. See Procedure 1 in the lesson plan for procedural options for student use of the photos/descriptions. 1. Ethnic Differentiation between Hutus and Tutsis, 1920’s http://modernhistoryproject2012.wordpress.com/history-of-hutu-tutsi-relations/ (First illustration, right side) The racist eugenics movement was popular in the United States and Europe in the 1920’s and 1930’s. It is this racism by European powers that influenced the interactions with Africans. Racism was the filter by which Bel- gian scientists, interested in understanding the nature of the relationship between the Hutu (75% majority) and the Tutsi (15-20% minority), measured heads, noses, skin color, height and body shape in an attempt to explain “scientifically” why the Tutsis were a “superior” tribe. The Belgian scientists concluded after their “re- search” that the Tutsis had European features, and this explained why they held the power despite being in the minority. This process brought institutional racism into Rwanda. 2. Tutsis Fled Ethnic Violence After Independence, 1959-1962 http://bengal.missouri.edu/~smwgz8/history.htm (Second image, first photo on page) Tutsis fled Rwanda after the Hutus rose to power and the resulting violence between the two groups when the Tutsi-led monarchy was overthrown. Over 150,000 Tutsis fled the country to Uganda and Burun- di, and those remaining in Rwanda were barred from political office after the 1962 constitution. -

Beck Sociolinguistic Profile Herero

SOCIOLINGUISTIC PROFILE OTJIHERERO IN NAMIBIA AND IN OMATJETE ROSE MARIE BECK Sociolinguistic profiles vary in scope, depth, differentiation etc. For the following pro- file I have chosen 11 aspects, of which it will not be possible to answer all of them with information pertaining to the Omatjete area (see map on p. 3). Much of what I write here is based on Rajmund Ohly‘s excellent sociolinguistic history of Herero (—The destabilization of the Herero language, 1987). Where it was possible I have in- cluded information specific to Omatjete. Aspects of a sociolinguistic profile 1. Classification, dialectal variation and differentiation, regional distribution, num- ber of speakers 2. Linguistic features: phonolgoy, morphology, syntax, lexicon (often with special reference to loanwords) 3. Who speaks it? 4. With which proficiency (L1, L2, L3 …) Grammatical, functional, cultural, ora- ture/literature? 5. Literacy 6. Domains (i.e. ”socio-culturally recognized spheres of activity‘ in which a lan- guage is used, a —social nexus which brings people together primarily for a cluster of purposes - … and primarily for a certain set of role-relations“ (Fishman 1965:72; 75). Spheres of activities may be: home, village, church, school, shop/market, recreation, wider communication, government and ad- ministration, work 7. Language attitudes and choice 8. Multilingualism and polyglossia 9. Language policy 10. Language development: - promotion and publication - codification - standardisation and education - foreign scholar involvement 11. Language vitality: positive, negative, and key factors 1 1. Classification, dialectal variation and differentiation, regional distribution, number of speakers Herero is a Bantu language (Niger Congo œ Benue-Kongo œ Bantoid œ Southern œ Narrow Bantu œ Central), classified according to Guthrie (1948) as R30. -

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes And

The Rwandan Genocide: Combating Stereotypes and Understanding the Origins Nicola Skakel Senior Honors Thesis Department of History April 9th 2018 Defense Committee: Dr. Susan K. Kent, Department of History, Primary Advisor Dr. Matthew Gerber, Department of History, Honors Council Representative Dr. Paul Shankman, Department of Anthropology, Advisor 1 Introduction On the 7th of April 1994, the small east African country of Rwanda erupted into one of the most deadly and intimate genocides the modern world had ever witnessed. Whilst the western world stood by and watched in just 100 days over 800,000 Rwandans out of a total population of 7 million, were systematically murdered in the most brutal and violent of ways. Those who were targeted made up the country’s minority ethnic group the Tutsis, and moderates from the majority group, the Hutus. For many, the legacy of Rwanda is a monstrous example of extreme pent up ethnic tensions that has its roots in European colonialism. In contrast, I will argue that the events not just of 1994 but also the unrest that proceeded it, arose from a highly complex culmination of long-standing historical tensions between ethnic groups that long pre-dated colonialism. In conjunction, a set of short-term triggers including foreign intervention, civil war, famine, state terrorism and ultimately the assassination of President Habyarimana also contributed to the outburst of genocide in 1994. Whilst it would be easy to place sole responsibility on European colonists for implementing a policy of divide and rule and therefore exacerbating ethnic tensions, it seems to me that genocide is never that cut and dried: it can never be explained by one factor. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Twa of Zambia's Kafue Flats

Twa of 1 Zambia’s Kafue Flats Southern Province Itezhi -Tezhi District Linguistic Survey Report With recommendations for Bible translation strategy Richard Mukang’ombe Daka Josephat Salimo Hachibamba Kenneth S. Sawka Survey Dates December 11 th to 12 th 2012 August 1 st to 6 th 2013 June 11 th to 16 th 2014 2 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ......................................................................4 1.1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................4 1.2. Terminology .................................................................................................................4 1.3. Historical Background ..................................................................................................4 1.4. Geographical locations ..................................................................................................7 1.5. Population ................................................................................................................... 13 1.6. Previous research ........................................................................................................ 15 1.7. Language borders and classification ............................................................................ 15 1.8. Social Pressures .......................................................................................................... 18 1.9. Livelihood.................................................................................................................. -

Randi-Markusen-Botsw

The Baherero of Botswana and a Legacy of Genocide Randi Markusen Member, Board of Directors World Without Genocide The Republic of Botswana is an African success story. It emerged in 1966 as a stable, multi-ethnic, democracy after eighty-one years as Bechuanaland, a British Protectorate. It was a model for progress, unlike many of its neighbors. Scholars from around the globe were eager to study and chronicle its people and formation. They hoped to learn what made it the exception, and so different from the rest of the continent.1 Investigations most often focused on two groups, the San, who were indigenous hunter-gathers, and the Tswana, the country’s largest ethnic group. But the scholars neglected other groups in their research. The Herero, who came to Botswana from Namibia in the early 1900s, long before independence, found themselves in that neglected category and were often unmentioned, even though their contributions were rich and their experiences compelling.2 The key to understanding the Herero in Botswana today lies in their past. A Short History of the Herero People The Herero have lived in the Southwest region of Africa for hundreds of years. They are believed to be descendants of pastoral migrants from Central Africa who made their way southwest during the 17th century and eventually inhabited what is now northern Namibia. In the middle of the 19th century they expanded farther south, seeking additional grassland for their cattle. This encroachment created conflicts with earlier migrants and indigenous groups. As a result, the Herero were engaged in on-and- off inter-tribal wars. -

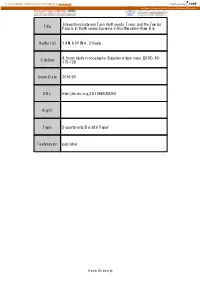

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Surrogate Surfaces: a Contextual Interpretive Approach to the Rock Art of Uganda

SURROGATE SURFACES: A CONTEXTUAL INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO THE ROCK ART OF UGANDA by Catherine Namono The Rock Art Research Institute Department of Archaeology School of Geography, Archaeology & Environmental Studies University of the Witwatersrand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 i ii Declaration I declare that this is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. Signed:……………………………….. Catherine Namono 5th March 2010 iii Dedication To the memory of my beloved mother, Joyce Lucy Epaku Wambwa To my beloved father and friend, Engineer Martin Wangutusi Wambwa To my twin, Phillip Mukhwana Wambwa and Dear sisters and brothers, nieces and nephews iv Acknowledgements There are so many things to be thankful for and so many people to give gratitude to that I will not forget them, but only mention a few. First and foremost, I am grateful to my mentor and supervisor, Associate Professor Benjamin Smith who has had an immense impact on my academic evolution, for guidance on previous drafts and for the insightful discussions that helped direct this study. Smith‘s previous intellectual contribution has been one of the corner stones around which this thesis was built. I extend deep gratitude to Professor David Lewis-Williams for his constant encouragement, the many discussions and comments on parts of this study. His invaluable contribution helped ideas to ferment. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general