Racial Discrimination: How Not to Do It

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microevolution: Species Concept Core Course: ZOOL3014 B.Sc. (Hons’): Vith Semester

Microevolution: Species concept Core course: ZOOL3014 B.Sc. (Hons’): VIth Semester Prof. Pranveer Singh Clines A cline is a geographic gradient in the frequency of a gene, or in the average value of a character Clines can arise for different reasons: • Natural selection favors a slightly different form along the gradient • It can also arise if two forms are adapted to different environments separated in space and migration (gene flow) takes place between them Term coined by Julian Huxley in 1838 Geographic variation normally exists in the form of a continuous cline A sudden change in gene or character frequency is called a stepped cline An important type of stepped cline is a hybrid zone, an area of contact between two different forms of a species at which hybridization takes place Drivers and evolution of clines Two populations with individuals moving between the populations to demonstrate gene flow Development of clines 1. Primary differentiation / Primary contact / Primary intergradation Primary differentiation is demonstrated using the peppered moth as an example, with a change in an environmental variable such as sooty coverage of trees imposing a selective pressure on a previously uniformly coloured moth population This causes the frequency of melanic morphs to increase the more soot there is on vegetation 2. Secondary contact / Secondary intergradation / Secondary introgression Secondary contact between two previously isolated populations Two previously isolated populations establish contact and therefore gene flow, creating an -

Clinal Variation at Microsatellite Loci Reveals Historical Secondary Intergradation Between Glacial Races of Coregonus Artedi (Teleostei: Coregoninae)

Evolution, 55(11), 2001, pp. 2274±2286 CLINAL VARIATION AT MICROSATELLITE LOCI REVEALS HISTORICAL SECONDARY INTERGRADATION BETWEEN GLACIAL RACES OF COREGONUS ARTEDI (TELEOSTEI: COREGONINAE) JULIE TURGEON1,2,3 AND LOUIS BERNATCHEZ1,4 1Groupe Interuniversitaire de Recherche en OceÂanographie du QueÂbec, DeÂpartement de biologie, Universite Laval, Ste-Foy, QueÂbec G1K 7P4, Canada 2E-mail: [email protected] 4E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Classical models of the spatial structure of population genetics rely on the assumption of migration-drift equilibrium, which is seldom met in natural populations having only recently colonized their current range (e.g., postglacial). Population structure then depicts historical events, and counfounding effects due to recent secondary contact between recently differentiated lineages can further counfound analyses of association between geographic and genetic distances. Mitochondrial polymorphisms have revealed the existence of two closely related lineages of the lake cisco, Coregonus artedi, whose signi®cantly different but overlaping geographical distributions provided a weak signal of past range fragmentation blurred by putative subsequent extensive secondary contacts. In this study, we analyzed geographical patterns of genetic variation at seven microsatellite loci among 22 populations of lake cisco located along the axis of an area covered by proglacial lakes 12,000±8000 years ago in North America. The results clearly con®rmed the existence of two genetically distinct races characterized by different sets of microsatellite alleles whose frequencies varied clinally across some 3000 km. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium analyses of isolation by distance revealed historical signal of gene ¯ow resulting from the nearly complete admixture of these races following neutral secondary contacts in their historical habitat and indicated that the colonization process occurred by a stepwise expansion of an eastern (Atlantic) race into a previously established Mississippian race. -

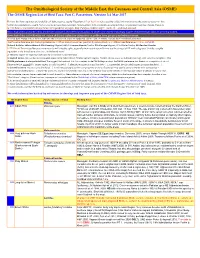

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Chv), Coastal Clay (Cc), and Plateau Harsh Voice (Phv

Heredity (1978),40 (3), 339-348 INTRA-SPECIFIC DIVERGENCE IN THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FROG RANIDELLA INSIGNIFERA I. THE EVIDENCE FROM GENE FREQUENCIES AND GENETIC DISTANCE JENEFER N. BLACKWELL* Department of Zoology, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia 6009 Received26.viii.77 SUMMARY Analysis of gene frequencies at ten enzyme loci (six polymorphic) failed to produce any evidence that races exist in the frog Ranidellainsign/fera associated with the edaphic feature of sand and clay based ponds. Most polymorphic loci exhibited macrogeographic uniformity of allele frequencies but in no case had any one allele become fixed in any one population. Nor were there any alleles unique to sand populations only or to clay populations only. Genetic distance algorithms failed to show any intra-specific divergence intermediate between inter-population and inter-sibling species levels. 1. INTRODUCTION ON the basis of aurally distinguishable differences in male mating call Main (1957) divided the leptodactylid frog species, Ranidella insignfera (recently removed from the genus Crinia by Blake, 1973) from south-western Australia into three call-types: Coastal harsh voice (Chv), Coastal clay (Cc), and Plateau harsh voice (Phv). Phv appeared to remain unchanged over its range and absence of intergrading calls with either Chv or Cc indicated a lack of gene flow. Phv was therefore regarded as a valid species, R. pseud- insignèra, reproductively isolated from R. insignjfera. Intergradation of calls, in some localities abruptly and in others in a more gradual manner, demon- strated the presence of gene flow between Chv and Cc which were then regarded as two races of one polytypic species, R. -

Natural Selection Along an Environmental Gradient: a Classic Cline in Mouse Pigmentation

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00425.x NATURAL SELECTION ALONG AN ENVIRONMENTAL GRADIENT: A CLASSIC CLINE IN MOUSE PIGMENTATION Lynne M. Mullen1,2 and Hopi E. Hoekstra1,3 1Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and The Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, 26 Oxford Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 2E-mail: [email protected] 3E-mail: [email protected] Received January 30, 2008 Accepted April 22, 2008 We revisited a classic study of morphological variation in the oldfield mouse (Peromyscus polionotus) to estimate the strength of selection acting on pigmentation patterns and to identify the underlying genes. We measured 215 specimens collected by Francis Sumner in the 1920s from eight populations across a 155-km, environmentally variable transect from the white sands of Florida’s Gulf coast to the dark, loamy soil of southeastern Alabama. Like Sumner, we found significant variation among populations: mice inhabiting coastal sand dunes had larger feet, longer tails, and lighter pigmentation than inland populations. Most striking, all seven pigmentation traits examined showed a sharp decrease in reflectance about 55 km from the coast, with most of the phenotypic change occurring over less than 10 km. The largest change in soil reflectance occurred just south of this break in pigmentation. Geographic analysis of microsatellite markers shows little interpopulation differentiation, so the abrupt change in pigmentation is not associated with recent secondary contact or reduced gene flow between adjacent populations. Using these genetic data, we estimated that the strength of selection needed to maintain the observed distribution of pigment traits ranged from 0.0004 to 21%, depending on the trait and model used. -

Taxonomic Aspects of Avian Hybridization

TAXONOMIC ASPECTS OF AVIAN HYBRIDIZATION LESTER L. SHORT INSTANCESof natural hybridizationfrequently pose difficult taxonomic problems.A decisionregarding the taxonomicstatus of hybridizingforms shouldbe basedupon an evaluationof all availablebiological information concerningtheir relationship.The paucity of availableinformation usually hamperstaxonomists treating hybridizationamong the higher vertebrates. Also it is difficult or impossibleto subjectsuch animals, and particularly animal populations,to experimentalstudy. Neverthelesstaxonomists must renderdecisions that reflect current availableknowledge. I offer the follow- ing discussionand definitionsin the hopeof facilitating suchdecisions by taxonomists,especially those working with terrestrial vertebrates. Ex- amplesforming the frameworkfor the discussionare drawn from the litera- ture of avian hybridization,including some work of my own. The widely divergent treatment of hybridizing forms evident in the recent ornithological literature demonstratesthe need for some guide- lines. At one extremethis divergenttreatment appearsto reflect a hold- over of typologicalthinking (e.g. Godfrey, 1966; Sutton, 1967), while the oppositeextreme (e.g. Phillips et al., 1964; West, 1962) resultsfrom an overly strict interpretationof the biologicalspecies definition in that different speciesdo not interbreed,and henceinterbreeding forms must be conspecific.The resultsof such divergenttreatment are taxonomicover- splittingin the formercase, and overlumpingin the latter. I definehybridization as the -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2017-B

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2017-B No. Page Title 01 02 Recognize additional species in the Aulacorhynchus “prasinus” toucanet complex 02 17 Treat the subspecies (A) spectabilis and (B) viridiceps as separate species from Eugenes fulgens (Magnificent Hummingbird) 03 23 Elevate Turdus rufopalliatus graysoni to species rank 04 26 Recognize newly described species Arremon kuehnerii 05 30 Revise the classification of the Icteridae: (A) add seven subfamilies; (B) split Leistes from Sturnella; (C) resurrect Ptiloxena for Dives atroviolaceus; and (D) modify the linear sequence of genera 06 34 Revise familial limits and the linear sequence of families within the nine- primaried oscines 07 42 Lump Acanthis flammea and Acanthis hornemanni into a single species 08 48 Split Lanius excubitor into two or more species 09 54 Add Mangrove Rail Rallus longirostris to the main list 10 56 Revise the generic classification and linear sequence of Anas 1 2017-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. Recognize additional species in the Aulacorhynchus “prasinus” toucanet complex Background: The AOU (1998) presently considers there to be just one species of Aulacorhynchus prasinus, which ranges from Mexico to Guyana and Bolivia. This taxon’s range combines the taxonomic oversight regions of both the North American and South American classification committees, so this proposal is designed to be submitted to both, with committee-structured voting sections at the end. This is easy to do biologically, because the taxa fall out fairly neatly split between North and South America. (The Panamanian blue-throated population breeding on Cerro Tacarcuna (subspecies cognatus) has (Hilty and Brown 1986) and has not been (Donegan et al. -

Why Was Darwin's View of Species Rejected by Twentieth Century

Biol Philos (2010) 25:497–527 DOI 10.1007/s10539-010-9213-7 Why was Darwin’s view of species rejected by twentieth century biologists? James Mallet Published online: 1 May 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract Historians and philosophers of science agree that Darwin had an understanding of species which led to a workable theory of their origins. To Darwin species did not differ essentially from ‘varieties’ within species, but were distin- guishable in that they had developed gaps in formerly continuous morphological variation. Similar ideas can be defended today after updating them with modern population genetics. Why then, in the 1930s and 1940s, did Dobzhansky, Mayr and others argue that Darwin failed to understand species and speciation? Mayr and Dobzhansky argued that reproductively isolated species were more distinct and ‘real’ than Darwin had proposed. Believing species to be inherently cohesive, Mayr inferred that speciation normally required geographic isolation, an argument that he believed, incorrectly, Darwin had failed to appreciate. Also, before the sociobiology revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, biologists often argued that traits beneficial to whole populations would spread. Reproductive isolation was thus seen as an adaptive trait to prevent disintegration of species. Finally, molecular genetic markers did not exist, and so a presumed biological function of species, repro- ductive isolation, seemed to delimit cryptic species better than character-based criteria like Darwin’s. Today, abundant genetic markers are available and widely used to delimit species, for example using assignment tests: genetics has replaced a Darwinian reliance on morphology for detecting gaps between species. -

Intergradation Between the Herring Gull Larus Argentatus and the Southern Herring Gull Larus Cachinnans in European Russia E

Russian Journal of Zoology, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1999, pp. 129–141. Translated from Zoologicheskii Zhurnal, Vol. 78, No. 3, 1999, pp. 334–348. Original Russian Text Copyright © 1999 by Panov, Monzikov. English Translation Copyright © 1999 by åÄàä “ç‡Û͇ /Interperiodica” (Russia). Intergradation between the Herring Gull Larus argentatus and the Southern Herring Gull Larus cachinnans in European Russia E. N. Panov and D. G. Monzikov Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117071 Russia Received January 8, 1998 Abstract—Five gull populations along a 2000-km transect, running from the Barents Sea coast in the Kola Pen- insula to Nizhegorodskaya oblast, were studied with respect to external morphology, vocalization, and DNA features. The transect crosses the easternmost part of the L. argentatus range, as well as areas of the Middle Volga basin inhabited by the gulls of cachinnans-like type. All the morphological and behavioral features proved to form a cline along the transect. Populations of the Barents Sea and the White Sea represent typical L. argentatus, while in those inhabiting the Upper and Middle Volga basin, L. cachinnans features predominate. The population of the Baltic Sea region is intermediate. Comparative DNA analysis by RAPD method has revealed introgression of L. argentatus genes southeastward, up to Nizhegorodskaya oblast, and those of L. cachinnans genes in the opposite direction, to the Baltic Sea. Two scenarios of introgression are discussed: via L. cachinnans omissus dispersal from Fennoscandia along the Volga basin and due to the expansion of the L. c. cachinans range to the north. Both processes may proceed simultaneously. -

The Nature of Race

Book. Submitted to Open Behavioral Genetics December 25, 2014 Published in Open Behavioral Genetics June 20, 2015 The Nature of Race John Fuerst1 Abstract: Racial constructionists, anti-naturalists, and anti-realists have challenged users of the biological race concept to provide and defend, from the perspective of biology, biological philosophy, and ethics, a biologically informed concept of race. In this paper, an onto- epistemology of biology is developed. What it is, by this, to be "biological real" and "biologically meaningful" and to represent a "biological natural division" is explained. Early 18th century race concepts are discussed in detail and are shown to be both sensible and not greatly dissimilar to modern concepts. A general biological race concept (GBRC) is developed. It is explained what the GBRC does and does not entail and how this concept unifies the plethora of specific ones, past and present. Other race concepts as developed in the philosophical literature are discussed in relation to the GBRC. The sense in which races are both real and natural is explained. Racial essentialism of the relational sort is shown to be coherent. Next, the GBRC is discussed in relation to anthropological discourse. Traditional human racial classifications are defended from common criticisms: historical incoherence, arbitrariness, cluster discordance, etc. Whether or not these traditional human races could qualify as taxa subspecies – or even species – is considered. It is argued that they could qualify as taxa subspecies by liberal readings of conventional standards. Further, it is pointed out that some species concepts potentially allow certain human populations to be designated as species. -

Hillis, D. M. 2020. the Detection and Naming of Geographic Variation

52 POINTS OF VIEW POINTS OF VIEW Herpetological Review, 2020, 51(1), 52–56. © 2020 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles The Detection and Naming of Geographic Variation Within Species Subspecies is the only taxonomic rank below species transitions, and some herpetologists began to abuse the concept recognized by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature of subspecies to designate arbitrary slices of continuous clines (1999). The use of subspecies to denote morphologically distinct as subspecies. This practice led to objections (e.g., Wilson and races that occupy different parts of a species range became Brown 1953) about the overuse of subspecies, as authors noted standard practice in zoology in the late 1800s (Mallet 2013). that different morphological features varied across a species Subspecies differ from species in that there are no reproductive range in different ways, so that the application of subspecies or genetic barriers among subspecies, so they typically exhibit was often arbitrary. More recently, other authors have argued a genetically continuous zone of intergradation from one that some subspecies designations are misleading about non- subspecies to the next across geographical space (Mayr 1969, morphological geographic variation or historical sublineages 1982). As noted by Mayr (1969), this means that subspecies are within species (Frost et al. 1992; Zink 2004). not units of evolution (independent evolutionary lineages, in Despite the objections to the often-arbitrary nature of modern terms). Instead, Mayr (1969) argued that subspecies subspecies, they continue to be useful in some contexts, such as represent geographic areas of recognizable morphology within field guides and studies of color-pattern selection, for designating a species, such that the appearance of the animals in one area of strikingly different-looking geographic races within species. -

Ecnomiohyla Rabborum. Rabb's Fringe-Limbed Treefrog Is One of the Most Significantly Threatened Amphibians in Central America

Ecnomiohyla rabborum. Rabb’s Fringe-limbed Treefrog is one of the most significantly threatened amphibians in Central America. This species is one of the most unusual anurans in the region because of its highly specialized reproductive mode, in which the eggs are laid in water-containing tree cavities and are attached to the interior of the cavity just above the water line. Females depart the tree cavity after oviposition, leaving the males to brood the eggs and the developing tadpoles, and parental care apparently extends to feeding the tadpoles flecks of skin from the male’s body (AmphibiaWeb site: accessed 24 July 2014). Mendelson et al. (2008) described this tree canopy treefrog from “montane cloudforest in the immediate vicinity of the town of El Valle de Antón” (Am- phibiaWeb site: accessed 24 July 2014) in central Panama, at elevations from 900 to 1,150 m. This mode of reproduction is typical of the members of the genus Ecnomiohyla, which now comprises 14 species (Batista et al. 2014) with a collective distribution extending from southern Mexico to northwestern South America (Colombia and Ecuador). This treefrog appears to be one of the many casualties of a sweep-through of Panama by the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in 2006. The arrival of this pathogen was anticipated by a team of amphibian biologists, who observed the disastrous effects of B. dendrobatidis on the popula- tions of anurans in the El Valle de Antón region. Individuals of E. rabbororum were taken into captivity and housed at Zoo Atlanta, but only a single male remains alive.