Natural Selection Along an Environmental Gradient: a Classic Cline in Mouse Pigmentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Cline Analysis As a Tool for Studying Genome-Wide Variation: a Case Study of Pollinator-Mediated Divergence in a Monkeyflower

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/036954; this version posted January 15, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Geographic cline analysis as a tool for studying genome-wide variation: a case study of pollinator-mediated divergence in a monkeyflower Sean Stankowski1,2, James M. Sobel3 and Matthew A. Streisfeld1 1Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, United States of America 2Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Biological Sciences, Binghamton University, Binghamton, New York, United States of America Keywords: ecotype formation, hybrid zone, Mimulus aurantiacus, pollinator isolation, reproductive isolation Running title: Genomics of pollinator-mediated divergence in a monkeyflower For consideration in the MEC special issue: The molecular basis of adaptation and ecological speciation - integrating genomic and molecular approaches; section: Ecological speciation genomics: advances and limitations 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/036954; this version posted January 15, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract A major goal of speciation research is to reveal the genomic signatures that accompany the speciation process. Genome scans are routinely used to explore genome-wide variation and identify highly differentiated loci that may contribute to ecological divergence, but they do not incorporate spatial, phenotypic, or environmental data that might enhance outlier detection. -

Recent Hybrids Recapitulate Ancient Hybrid Outcomes

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Ecology Center Publications Ecology Center 5-1-2020 Recent Hybrids Recapitulate Ancient Hybrid Outcomes Samridhi Chaturvedi Utah State University Lauren K. Lucas Utah State University C. Alex Buerkle University of Wyoming James A. Fordyce University of Tennessee, Knoxville Matthew L. Forister University of Nevada, Reno Chris C. Nice Texas State University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/eco_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Chaturvedi, S., Lucas, L.K., Buerkle, C.A. et al. Recent hybrids recapitulate ancient hybrid outcomes. Nat Commun 11, 2179 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15641-x This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ecology Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ecology Center Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Samridhi Chaturvedi, Lauren K. Lucas, C. Alex Buerkle, James A. Fordyce, Matthew L. Forister, Chris C. Nice, and Zachariah Gompert This article is available at DigitalCommons@USU: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/eco_pubs/122 ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15641-x OPEN Recent hybrids recapitulate ancient hybrid outcomes Samridhi Chaturvedi1,2,3, Lauren K. Lucas1, C. Alex Buerkle 4, James A. Fordyce5, Matthew L. Forister6, ✉ Chris C. Nice7 & Zachariah Gompert1,2 Genomic outcomes of hybridization depend on selection and recombination in hybrids. Whether these processes have similar effects on hybrid genome composition in con- 1234567890():,; temporary hybrid zones versus ancient hybrid lineages is unknown. -

Natural Selection Maintains a Singlelocus Leaf Shape Cline In

Molecular Ecology (2013) 22, 552–564 doi: 10.1111/mec.12057 Natural selection maintains a single-locus leaf shape cline in Ivyleaf morning glory, Ipomoea hederacea BRANDON E. CAMPITELLI* and JOHN R. STINCHCOMBE*† *Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks Street, Toronto, ON Canada M5S 3B2, †Center for the Analysis of Genome Evolution and Function, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks Street, Toronto, ON M5S 3B2, Canada Abstract Clines in phenotypic traits with an underlying genetic basis potentially implicate natu- ral selection. However, neutral evolutionary processes such as random colonization, spatially restricted gene flow, and genetic drift could also result in similar spatial pat- terns, especially for single-locus traits because of their susceptibility to stochastic events. One way to distinguish between adaptive and neutral mechanisms is to com- pare the focal trait to neutral genetic loci to determine whether neutral loci demon- strate clinal variation (consistent with a neutral cline), or not. Ivyleaf morning glory, Ipomoea hederacea, exhibits a latitudinal cline for a Mendelian leaf shape polymor- phism in eastern North America, such that lobed genotypes dominate northern popula- tions and heart-shaped genotypes are restricted to southern populations. Here, we evaluate potential evolutionary mechanisms for this cline by first determining the allele frequencies at the leaf shape locus for 77 populations distributed throughout I. hederacea’s range and then comparing the geographical pattern at this locus to neu- tral amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) loci. We detected both significant clinal variation and high genetic differentiation at the leaf shape locus across all popu- lations. In contrast, 99% of the putatively neutral loci do not display clinal variation, and I. -

Genetic Exchange Across a Hybrid Zone Within the Iberian Endemic

Molecular Ecology (2005) 14, 245–254 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02390.x GeneticBlackwell Publishing, Ltd. exchange across a hybrid zone within the Iberian endemic golden-striped salamander, Chioglossa lusitanica F. SEQUEIRA,*† J. ALEXANDRINO,*§ S. ROCHA,* J. W. ARNTZEN*‡ and N. FERRAND*† *CIBIO/UP-Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Campus Agrário de Vairão, Rua Padre Armando Quintas, 4485–661 Vairão, Portugal, †Departamento de Zoologia e Antropologia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Praça Gomes Teixeira, 4099-002 Porto, Portugal, ‡National Museum of Natural History, PO Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands, §Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, 3101 Valley Life Science Building # 3160, Berkeley, CA 94720– 3160, USA Abstract The study of hybrid zones resulting from Pleistocene vicariance is central in examining the potential of genetically diverged evolutionary units either to introgress and merge or to proceed with further isolation. The hybrid zone between two mitochondrial lineages of Chioglossa lusitanica is located near the Mondego River in Central Portugal. We used mito- chondrial and nuclear diagnostic markers to conduct a formal statistical analysis of the Chioglossa hybrid zone in the context of tension zone theory. Key results are: (i) cline centres are not coincident for all markers, with average widths of ca. 2–15 km; (ii) heterozygote deficit was not observed across loci near the transect centre; (iii) associations of parental allele combinations (‘linkage disequilibrium’ R) were not detected either across loci or across the transect. These observations suggest that the Chioglossa hybrid zone is not a tension zone with strong selection against hybrids but instead one shaped mostly by neutral mixing. -

Microevolution: Species Concept Core Course: ZOOL3014 B.Sc. (Hons’): Vith Semester

Microevolution: Species concept Core course: ZOOL3014 B.Sc. (Hons’): VIth Semester Prof. Pranveer Singh Clines A cline is a geographic gradient in the frequency of a gene, or in the average value of a character Clines can arise for different reasons: • Natural selection favors a slightly different form along the gradient • It can also arise if two forms are adapted to different environments separated in space and migration (gene flow) takes place between them Term coined by Julian Huxley in 1838 Geographic variation normally exists in the form of a continuous cline A sudden change in gene or character frequency is called a stepped cline An important type of stepped cline is a hybrid zone, an area of contact between two different forms of a species at which hybridization takes place Drivers and evolution of clines Two populations with individuals moving between the populations to demonstrate gene flow Development of clines 1. Primary differentiation / Primary contact / Primary intergradation Primary differentiation is demonstrated using the peppered moth as an example, with a change in an environmental variable such as sooty coverage of trees imposing a selective pressure on a previously uniformly coloured moth population This causes the frequency of melanic morphs to increase the more soot there is on vegetation 2. Secondary contact / Secondary intergradation / Secondary introgression Secondary contact between two previously isolated populations Two previously isolated populations establish contact and therefore gene flow, creating an -

Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja

Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja To cite this version: Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja. Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. American Naturalist, Uni- versity of Chicago Press, 2018, 191 (2), pp.155-172. 10.1086/695136. hal-01945350 HAL Id: hal-01945350 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01945350 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License vol. 191, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2018 Synthesis Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger K. Butlin1,2,* and Carole M. Smadja1,3 1. Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study, Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa; 2. Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, United Kingdom; and Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Tjärnö SE-45296 Strömstad, Sweden; 3. Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5554 (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique–Institut de Recherche pour le Développement–École pratique des hautes études), Université de Montpellier, 34095 Montpellier, France Submitted March 15, 2017; Accepted August 28, 2017; Electronically published December 15, 2017 abstract: During the process of speciation, populations may di- Introduction verge for traits and at their underlying loci that contribute barriers Understanding how reproductive isolation evolves is key fl to gene ow. -

Clinal Variation at Microsatellite Loci Reveals Historical Secondary Intergradation Between Glacial Races of Coregonus Artedi (Teleostei: Coregoninae)

Evolution, 55(11), 2001, pp. 2274±2286 CLINAL VARIATION AT MICROSATELLITE LOCI REVEALS HISTORICAL SECONDARY INTERGRADATION BETWEEN GLACIAL RACES OF COREGONUS ARTEDI (TELEOSTEI: COREGONINAE) JULIE TURGEON1,2,3 AND LOUIS BERNATCHEZ1,4 1Groupe Interuniversitaire de Recherche en OceÂanographie du QueÂbec, DeÂpartement de biologie, Universite Laval, Ste-Foy, QueÂbec G1K 7P4, Canada 2E-mail: [email protected] 4E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Classical models of the spatial structure of population genetics rely on the assumption of migration-drift equilibrium, which is seldom met in natural populations having only recently colonized their current range (e.g., postglacial). Population structure then depicts historical events, and counfounding effects due to recent secondary contact between recently differentiated lineages can further counfound analyses of association between geographic and genetic distances. Mitochondrial polymorphisms have revealed the existence of two closely related lineages of the lake cisco, Coregonus artedi, whose signi®cantly different but overlaping geographical distributions provided a weak signal of past range fragmentation blurred by putative subsequent extensive secondary contacts. In this study, we analyzed geographical patterns of genetic variation at seven microsatellite loci among 22 populations of lake cisco located along the axis of an area covered by proglacial lakes 12,000±8000 years ago in North America. The results clearly con®rmed the existence of two genetically distinct races characterized by different sets of microsatellite alleles whose frequencies varied clinally across some 3000 km. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium analyses of isolation by distance revealed historical signal of gene ¯ow resulting from the nearly complete admixture of these races following neutral secondary contacts in their historical habitat and indicated that the colonization process occurred by a stepwise expansion of an eastern (Atlantic) race into a previously established Mississippian race. -

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

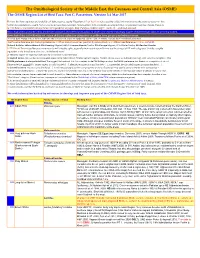

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Rapid Evolution of a Geographic Cline in Size in an Introduced

R EPORTS nificant increase in the probability of spawning ob- 30. Two other cases exist in which the traits that form the 32. Supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering served for populations of females with males of the proximate basis of reproductive isolation have known Research Council of Canada (NSERC) fellowship to other ecomorph from different lakes versus males of adaptive significance. These are beak and body size in H.D.R., NSERC research grants to D.S., and a National the other ecomorph from the same lake was significant Darwin’s finches in the Gala«pagos Islands [P. T. Boag and Science FoundationÐNATO (USA) fellowship to in the absence of the phylogenetic correction (paired t P. R. Grant, Science 214, 82 (1981); L. M. Ratcliffe and J.W.B. E. Taylor provided unpublished microsatellite ϭ ϭ test, t5 3.37, P 0.020) (Fig. 2, comparison C). P. R. Grant, Anim. Behav. 31, 1139 (1983); T. D. Price, DNA data. A. Agrawal, S. Morgan, and K. Rozalska 28. No significant difference in microsatellite or mtDNA P. R. Grant, H. L. Gibbs, P. T. Boag, Nature 309, 787 helped conduct mating trials. T. Day and M. Linde«n divergence is detected between pairs of populations (1984)] and copper tolerance in Mimulus [M. R. MacNair provided technical support. S. Otto, M. Whitlock, (conspecific pairs excluded) from the same versus a and P. Christie, Heredity 50, 295 (1983); P. Christie and three reviewers, and the rest of the Schluter Otto different environment [microsatellite, analysis of M. R. MacNair, J. Hered. 75, 510 (1984)]. -

Chv), Coastal Clay (Cc), and Plateau Harsh Voice (Phv

Heredity (1978),40 (3), 339-348 INTRA-SPECIFIC DIVERGENCE IN THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FROG RANIDELLA INSIGNIFERA I. THE EVIDENCE FROM GENE FREQUENCIES AND GENETIC DISTANCE JENEFER N. BLACKWELL* Department of Zoology, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Western Australia 6009 Received26.viii.77 SUMMARY Analysis of gene frequencies at ten enzyme loci (six polymorphic) failed to produce any evidence that races exist in the frog Ranidellainsign/fera associated with the edaphic feature of sand and clay based ponds. Most polymorphic loci exhibited macrogeographic uniformity of allele frequencies but in no case had any one allele become fixed in any one population. Nor were there any alleles unique to sand populations only or to clay populations only. Genetic distance algorithms failed to show any intra-specific divergence intermediate between inter-population and inter-sibling species levels. 1. INTRODUCTION ON the basis of aurally distinguishable differences in male mating call Main (1957) divided the leptodactylid frog species, Ranidella insignfera (recently removed from the genus Crinia by Blake, 1973) from south-western Australia into three call-types: Coastal harsh voice (Chv), Coastal clay (Cc), and Plateau harsh voice (Phv). Phv appeared to remain unchanged over its range and absence of intergrading calls with either Chv or Cc indicated a lack of gene flow. Phv was therefore regarded as a valid species, R. pseud- insignèra, reproductively isolated from R. insignjfera. Intergradation of calls, in some localities abruptly and in others in a more gradual manner, demon- strated the presence of gene flow between Chv and Cc which were then regarded as two races of one polytypic species, R. -

Analysis of Host-Parasite Cospeciation: Effects of Spatial and Temporal Scale

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 Analysis of Host-Parasite Cospeciation: Effects of Spatial and Temporal Scale. James W. Demastes Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Demastes, James W., "Analysis of Host-Parasite Cospeciation: Effects of Spatial and Temporal Scale." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6331. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6331 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Coevolution and Cospeciation in a Bark-Beetle Fungal Symbiosis

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2015 Coevolution and cospeciation in a bark-beetle fungal symbiosis Ryan Russell Bracewell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bracewell, Ryan Russell, "Coevolution and cospeciation in a bark-beetle fungal symbiosis" (2015). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10784. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10784 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COEVOLUTION AND COSPECIATION IN A BARK-BEETLE FUNGAL SYMBIOSIS By RYAN RUSSELL BRACEWELL B.S. Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, 2002 M.S. Ecology, Utah State University, Logan, UT, 2009 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forestry and Conservation Sciences The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2015 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Diana Six, Chair Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences Dr. Jeffrey Good Division of Biological Sciences Dr. John McCutcheon Division of Biological Sciences Dr. Michael Schwartz USDA Forest Service/College of Forestry and Conservation Dr. Ylva Lekberg MPG Ranch/College of Forestry and Conservation ProQuest Number: 10096854 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.