The Forgotten Click of American Toe-Tap, 1925 – 1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

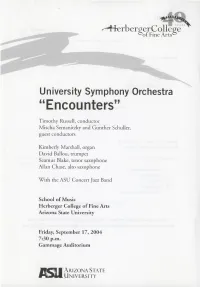

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Proper Attire

2021-2022 Welcome! We are so happy to have you in our dance program. Together, we With the exception of dance shoes, will work to instill a love of dance that can last a lifetime. Please review the many of the required dancewear following guidelines and let us know if you have any questions. items and hair supplies are available for sale in our Pro Shop. PROPER ATTIRE: HAIR: For ALL Ballet classes (Dance Tots, Fairytale Ballerinas, PreBallet, Ballet), hair must be pulled away from the face and pinned securely into a ballet bun (no bangs for ages 6 and up). For ALL other classes, hair must be in a ponytail, secured off the shoulders and away from the face. ------------------------------------------ ------ TEENY DANCERS: Female – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare Feet. Dance attire (leotard, tights, ballet slippers**) may be worn if desired. Male – Non-baggy athletic/bike shorts & t-shirt. Bare feet. Parents – Comfortable clothes that you can move in! Bare feet. DANCE TOTS: Female – Light pink leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male – White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PREBALLET: Female – Light blue leotard*, light pink footed tights**, pink leather ballet slippers*** Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts or tights, white socks, black ballet slippers PRE-TAP/HIP-HOP: Female – Light blue leotard, light pink OR light suntan footed tights**. Tan Tap Shoes / Tan Slip-on Jazz Shoes. • Optional – Girls may also wear light blue or black dance skirt or dance shorts over their leotard & tights. Male - White t-shirt, black bike shorts, Black crew socks. -

The Karsch & Fried Families

The Karsch & Fried Families Initial Research Prepared for Blair Adam Karsch By Michael Goldstein July 15, 2008 The Karsch Family From the Ukraine to America Kherson Gubernia, America and the Karsch Family The Karsch family ancestral origins are from the Kherson Gubernia and the towns of Kherson and Odessa. These locations are in today’s Ukraine. Little is known of the family before its arrival in the USA other than that the earliest identified ancestor was Zelig Karsch who appears to have lived somewhere in this area. Since records are kept by town no further European research is being undertaken until we are reasonably certain of the town of origin. Kherson Gubernia was an administrative-territorial unit in Russian-ruled Southern Ukraine between the Dnieper and Dniester Rivers. One of the three gubernias created after New Russia gubernia was abolished in 1802, it was called Mykolaiv gubernia until 1803, when Kherson became the new capital. From 1809 the gubernia had five counties: Kherson, Oleksandriia, Olviopil, Tyraspil, and Yelysavethrad. Odesa County was added in 1825. Odesa and their vicinity were governed separately: Odesa by a gradonachalnik answerable directly to the tsar and (from 1822) the governor-general of New Russia and Bessarabia, and Mykolaiv by a military governor. The gubernia had a population of about 1,330,000 in 1863, 2,027,000 in 1885, 2,733,600 in 1897, and 3,744,600 in 1914. In the 1850s Jews consisted 6 to 7 percent and in 1914, 12 percent. In- migration accounted for much of the population growth; e.g. -

A Comparative Mechanical Analysis of the Pointe Shoe Toe Box an in Vitro Study Bryan W

0363-5465/98/2626-0555$02.00/0 THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, Vol. 26, No. 4 © 1998 American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine A Comparative Mechanical Analysis of the Pointe Shoe Toe Box An In Vitro Study Bryan W. Cunningham,* MSc, Andrea F. DiStefano,† PT, Natasha A. Kirjanov,‡ Stuart E. Levine,* MD, and Lew C. Schon,*§ MD From *The Orthopaedic Biomechanics Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Union Memorial Hospital, Baltimore, †Health South Spine Center, St. Joseph Hospital, Towson, and the ‡Ballet Theatre of Annapolis, Annapolis, Maryland ABSTRACT ical demands on the body while requiring the production of aesthetic and graceful movements. From the 1581 in- Dancing en pointe requires the ballerina to stand on troduction of ballet at the French Court (attributed to her toes, which are protected only by the pointe shoe Catherine de Medici), the popularization of this art form toe box. This protection diminishes when the toe box by Louis XIV, and the 1661 creation of the Academie loses its structural integrity. The objectives of this study Royale de Danse,2 the technique of ballet has become more were 1) to quantify the comparative structural static and fatigue properties of the pointe shoe toe box, and demanding, requiring refinement of the dancer’s strength, 2) to evaluate the preferred shoe characteristics as technique, and tools. This was highlighted by Marie determined by a survey of local dancers. Five different Taglioni, who, in 1832, was the first to dance en pointe. pointe shoes (Capezio, Freed, Gaynor Minden, Leo’s, This was originally done with soft satin slippers contain- and Grishko) were evaluated to quantify the static stiff- ing a leather sole. -

CWLT Student Guide

Cold Weather Leader Training STUDENT GUIDE Northern Tier National High Adventure Boy Scouts of America Northern Tier National High Adventure Cold Weather Leader Training Student Guide Table of Contents About Okpik and CWLT ................................................................................................................ 4 How Do We Prepare Mentally and Physically? ............................................................................. 5 What are the risks? (Risk Advisory) ............................................................................................... 6 How do I prevent problems? ........................................................................................................... 7 General policies and information .................................................................................................... 7 How do I get there? ......................................................................................................................... 8 What do I need to pack?.................................................................................................................. 9 Patches and Program Awards ....................................................................................................... 12 Feed the Cold (a pre-CWLT assignment) ..................................................................................... 13 Sample Course Schedule (subject to change) ............................................................................... 14 Cold Weather Camping................................................................................................................ -

XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY in the LAKE (1947, 105 Min)

September 22, 2015 (XXXI:4) Robert Montgomery, LADY IN THE LAKE (1947, 105 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Directed by Robert Montgomery Written by Steve Fisher (screenplay) based on the novel by Raymond Chandler Produced by George Haight Music by David Snell and Maurice Goldman (uncredited) Cinematography by Paul Vogel Film Editing by Gene Ruggiero Art Direction by E. Preston Ames and Cedric Gibbons Special Effects by A. Arnold Gillespie Robert Montgomery ... Phillip Marlowe Audrey Totter ... Adrienne Fromsett Lloyd Nolan ... Lt. DeGarmot Tom Tully ... Capt. Kane Leon Ames ... Derace Kingsby Jayne Meadows ... Mildred Havelend Pink Horse, 1947 Lady in the Lake, 1945 They Were Expendable, Dick Simmons ... Chris Lavery 1941 Here Comes Mr. Jordan, 1939 Fast and Loose, 1938 Three Morris Ankrum ... Eugene Grayson Loves Has Nancy, 1937 Ever Since Eve, 1937 Night Must Fall, Lila Leeds ... Receptionist 1936 Petticoat Fever, 1935 Biography of a Bachelor Girl, 1934 William Roberts ... Artist Riptide, 1933 Night Flight, 1932 Faithless, 1931 The Man in Kathleen Lockhart ... Mrs. Grayson Possession, 1931 Shipmates, 1930 War Nurse, 1930 Our Blushing Ellay Mort ... Chrystal Kingsby Brides, 1930 The Big House, 1929 Their Own Desire, 1929 Three Eddie Acuff ... Ed, the Coroner (uncredited) Live Ghosts, 1929 The Single Standard. Robert Montgomery (director, actor) (b. May 21, 1904 in Steve Fisher (writer, screenplay) (b. August 29, 1912 in Marine Fishkill Landing, New York—d. September 27, 1981, age 77, in City, Michigan—d. March 27, age 67, in Canoga Park, California) Washington Heights, New York) was nominated for two Academy wrote for 98 various stories for film and television including Awards, once in 1942 for Best Actor in a Leading Role for Here Fantasy Island (TV Series, 11 episodes from 1978 - 1981), 1978 Comes Mr. -

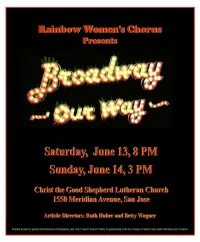

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

Support- Attire for 2021-2022 Dance Season

Support- Attire for 2021-2022 Dance Season Monday, Tuesday & Wednesday Classes need to wear the NEW theatrical tank Lavender Leotard and Lavender skirt Thursday classes need wear Black Leotard and Black Skirt ALL LEVEL LEOTARDS (AND EVERYTHING ELSE IS AVAILABLE HERE AS WELL) SHOULD BE PURCHASED AT OUR STUDIO STORE, THROUGH DISCOUNT DANCE. For All Classes at the SGB no midriff or cleavage should be visible with any attire at any time. Cover ups should be appropriate for the class they are taking. During Cold weather a Ballet Sweater (not a regular sweater or shirt) may be worn until a dancer is warm or the teacher requests it to be removed. www.discountdance.com Click on “Find Teacher” in the upper left corner Type in Goldsboro, NC Look for Mary Franklin, School of Goldsboro Ballet Click on “Studio Page” Ballet Classes- All dancers must wear -Ballet Pink Tights (ages 7 and up need to wear seamed or mock-seamed PERFORMANCE tights for Performances ONLY) -Ballet PINK shoes (All dancers under 10 should wear a FULL soled Ballet shoe). LEATHER BALLET shoes are required for PERFORMANCE. -Boys should be in a Black Ballet shoe (canvas is acceptable for boys). Tap Classes- -Support dancers should be in a Tan “Mary Jane” style tap shoe. It does not matter the brand, the buckle/snap/tie or Velcro. -Boys should be in a Black Oxford style tap shoe (slip on or Tie are acceptable) Jazz Classes- -All Jazz students should wear Tan Jazz Shoes (or Caramel). The brand should be selected by what’s most comfortable for the individual dancer. -

Bullets High Five

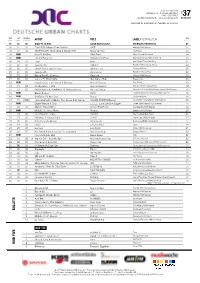

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 37 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 03.09.2020 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 08.09.2020 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 03 02 Drake Ft. Lil Durk Laugh Now Cry Later OVO/Republic/UMI/Universal 01 02 01 03 Cardi B Ft. Megan Thee Stallion WAP Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 03 02 04 A$AP Ferg Ft. Nicki Minaj & MadeinTYO Move Ya Hips RCA/Sony 02 04 NEW Nas Ft. Hit-Boy Ultra Black Mass Appeal/Universal 04 05 NEW Capital Bra x Cro Frühstück In Paris Bra Musik/Urban/VEC/Universal 05 06 04 07 Tyga Ibiza Last Kings/Columbia/Sony 01 07 08 08 Apache 207 Bläulich TwoSides/Four Music/Sony 03 08 06 03 Jawsh 685 x Jason Derulo Savage Love Columbia/Sony 06 09 07 05 Apache 207 Unterwegs TwoSides/Four/Sony 03 10 16 02 Burna Boy Ft. Stormzy Real Life Atlantic/WMI/Warner 10 11 05 04 Juicy J Ft. Wiz Khalifa Gah Damn High Trippy/eOne 05 12 NEW Headie One Ft. AJ Tracey & Stormzy Ain't It Different Epic/Sony 12 13 18 09 Kynda Gray Ft. RIN Ayo Technology Division/Gold League/Sony 12 14 13 02 David Guetta & HUMAN(X) Ft. Various Artists Pa' La Cultura What A DJ/HUMAN(X)/Warner Latina/WMI/Warner 13 15 NEW Bausa & Juju 2012____ Downbeat/Warner Germany/WMD/Warner 15 16 NEW 24kGoldn Ft. Iann Dior Mood Columbia/Sony 16 17 10 10 Jack Harlow Ft. -

Fall Schedule Booklet 7-5-21 UPDATE.Pub

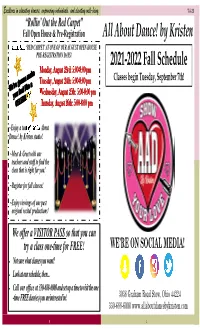

Excellence in educating dancers, empowering individuals, and elevating well-being. 7-5-21 “Rollin’ Out the Red Carpet” Fall Open House & Pre -Registration All About Dance! by Kristen WALK THE ‘RED CARPET’ AT ONE OF OUR AUGUST OPEN HOUSE PRE -REGISTRATION DAYS! 2021-2022 Fall Schedule Monday, August 23rd: 5:005:00----8:008:00 pm Tuesday, August 24th: 5:005:00----8:008:00 pm Classes begin Tuesday, September 7th! Wednesday, August 25th: 5:005:00----8:008:00 pm Thursday, August 26th: 5:005:00----8:008:00 pm ~Enjoy a tour of the All About Dance! by Kristen studio! ~Meet & Greet with our teachers and staff to find the class that is right for you! ~Register for fall classes! ~Enjoy viewings of our past original recital productions! We offer a VISITOR PASS so that you can try a class one -time for FREE! WE’RE ON SOCIAL MEDIA! • Not sure what classes you want? • Look at our schedule, then... • Call our office at 330 -688 -6000 and set up a time to visit the one -time FREE class(es) you are interested in! 3038 Graham Road Stow, Ohio 44224 330-688-6000 www.allaboutdancebykristen.com 8 1 NEWExcellence 2021-2022 in educating INSTRUCTORS dancers, empowering individuals, and elevating well-being. Erika Hunt (EH) is a native of Northeast Ohio and began her training in 1990 at the University of Akron Dance Institute. While at the Institute, Erika had the AADbK Delegates of Dance 2021-2022 pleasure of working with a diverse and talented faculty including Ana Lobe, Tatyana and Roman Mazur, Richard Dickinson, Jane Startzman, Lana Carroll, Delegates of Dance ~ A perfect opportunity to be the face of All About Dance! by Kristen! Andrew Carroll, MaryAnn Black, Amy Miller, Christina Foisie, and Felise Bagley. -

Alice Guy Blaché

Alice Guy Blaché Also Known As: Alice Blache, Alice Guy, Alice Guy-Blaché Lived: July 1, 1873 - March 24, 1968 Worked as: assistant director, co-director, co-producer, co-screenwriter, director, film company owner, lecturer, producer, screenwriter, secretary, writer Worked In: France, United States by Alison McMahan From 1896 to 1906 Alice Guy was probably the only woman film director in the world. She had begun as a secretary for Léon Gaumont and made her first film in 1896. After that first film, she directed and produced or supervised almost six hundred silent films ranging in length from one minute to thirty minutes, the majority of which were of the single-reel length. In addition, she also directed and produced or supervised one hundred and fifty synchronized sound films for the Gaumont Chronophone. Her Gaumont silent films are notable for their energy and risk-taking; her preference for real locations gives the extant examples of these Gaumont films a contemporary feel. As Alan Williams has described her influence, Alice Guy “created and nurtured the mood of excitement and sheer aesthetic pleasure that one senses in so many pre-war Gaumont films, including the ones made after her departure from the Paris studio” (57). Most notable of her Gaumont period films is La Vie du Christ (1906), a thirty-minute extravaganza that featured twenty-five sets as well as numerous exterior locations and over three hundred extras. In early 1907, Guy resigned her position as head of Gaumont’s film production arm in Paris although she did not end her business relationship with Gaumont. -

The Silent Film Project

The Silent Film Project Films that have completed scanning – Significant titles in bold: May 1, 2018 TITLE YEAR STUDIO DIRECTOR STAR 1. [1934 Walt Disney Promo] 1934 Disney 2. 13 Washington Square 1928 Universal Melville W. Brown Alice Joyce 3. Adventures of Bill and [1921] Pathegram Robert N. Bradbury Bob Steele Bob, The (Skunk, The) 4. African Dreams [1922] 5. After the Storm (Poetic [1935] William Pizor Edgar Guest, Gems) Al Shayne 6. Agent (AKA The Yellow 1922 Vitagraph Larry Semon Larry Semon Fear), The 7. Aladdin And The 1917 Fox Film C. M. Franklin Francis Wonderful Lamp Carpenter 8. Alexandria 1921 Burton Holmes Burton Holmes 9. An Evening With Edgar A. [1938] Jam Handy Louis Marlowe Edgar A. Guest Guest 10. Animals of the Cat Tribe 1932 Eastman Teaching 11. Arizona Cyclone, The 1934 Imperial Prod. Robert E. Tansey Wally Wales 12. Aryan, The 1916 Triangle William S. Hart William S. Hart 13. At First Sight 1924 Hal Roach J A. Howe Charley Chase 14. Auntie's Portrait 1914 Vitagraph George D. Baker Ethel Lee 15. Autumn (nature film) 1922 16. Babies Prohibited 1913 Thanhouser Lila Chester 17. Barbed Wire 1927 Paramount Rowland V. Lee Pola Negri 18. Barnyard Cavalier 1922 Christie Bobby Vernon 19. Barnyard Wedding [1920] Hal Roach 20. Battle of the Century 1927 Hal Roach Clyde Bruckman Oliver Hardy, Stan Laurel 21. A Beast at Bay 1912 Biograph D.W. Griffith Mary Pickford 22. Bebe Daniels & Ben Lyon 1931- Bebe Daniels, home movies 1935 Ben Lyon 23. Bell Boy 13 1923 Thomas Ince William Seiter Douglas Maclean 24.