Uganda at a Glance: 2001-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Assoc

REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Assoc. Prof. Yasin Olum (PhD) The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung but rather those of the author. MULTIPARTY POLITICS IN UGANDA i REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 51A, Prince Charles Drive, Kololo P. O. Box 647, Kampala Tel. +256 414 25 46 11 www.kas.de ISBN: 978 - 9970 - 153 - 09 - 1 Author Assoc. Prof. Yasin Olum (PhD) © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ii MULTIPARTY POLITICS IN UGANDA Table of Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................... 1 List of Tables ................................................................................................. 3 Acronyms/Abbreviations ................................................................................. 4 Introduction .................................................................................................. 7 PART 1: THE MULTIPARTY ENVIRONMENT: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND INSTITUTIONS ........................... 11 Chapter One: ‘Democratic’ Transition in Africa and the Case of Uganda ........................... 12 Introduction ................................................................................................... 12 Defining Democracy -

Just Die Quietly: Domestic Violence and Women's Vulnerability to Hiv in Uganda

August 2003 Vol. 15, No. 15(A) JUST DIE QUIETLY: DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND WOMEN’S VULNERABILITY TO HIV IN UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Uganda .............................................................................................................................................1 I. SUMMARY..............................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................................................5 To the Government of Uganda .................................................................................................................5 To Donors and Regional and International Organizations: ......................................................................6 III. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................8 Uganda: Historical, Political, and Economic Context ..............................................................................9 The Legal System, Education, and Health..............................................................................................11 HIV/AIDS in Uganda .............................................................................................................................14 Domestic Violence in Uganda................................................................................................................16 Women’s -

Better Together

Better Together: Inclusive Power Sharing and Mutidimensional Conflicts Chelsea Johnson Ph.D. Candidate, Political Science University of California, Berkeley DRAFT: 12 DECEMBER 2014 PLEASE DO NOT CIRCULATE Abstract: Theories that focus on signaling and commitment credibility, as well as those on institutional design, suggest that all-inclusive power-sharing settlements are more likely to breakdown where the armed oPPosition is fractionalized. In contrast, I argue that inclusivity reduces the capacity for insurgents to defect from their commitments to sharing power. The implementation of any Power-sharing bargain is likely to generate winners and losers within grouPs, contributing to sPlintering, and disgruntled elites are more likely to have access to the resources necessary to return to the battlefield where other active insurgencies have been excluded from the Peace Process. I illustrate this mechanism with an in-depth analysis of two dyadic peace processes in Uganda, both of which resulted in rebel splintering and continued violence. Finally, a cross-national analysis of 238 settlement dyads suPPorts the exPectation that inclusive Power-sharing settlements are significantly more likely to result in conflict termination. Johnson 2 Recent rePorts indicate that the number of active militias is Proliferating in South Sudan, where conflict in the region has reemerged, and even intensified, desPite its recent independence.1 Meanwhile, the Intergovernmental Authority on DeveloPment (IGAD) is attempting to broker a Peace bargain between President Kiir’s government and the Sudan PeoPle’s Liberation Army-In Opposition (SPLA-IO). While Politically exPedient, IGAD’s decision to focus its mediation on the Primary threat to the nascent South Sudanese government—to the exclusion of two dozen other armed grouPs—has the potential to be counter-productive. -

UGANDAN REFUGEES in the SUDAN Part I: the Long Journey

UGANDAN REFUGEES IN THE SUDAN Part I: The Long Journey by Barbara Harrell - Bond 19821No. 48 Africa [BHB-1-'821 Around 200,000 Ugandans have up since 1979, most having fled sought refuge in the Sudan. from Uganda's infamous elections Many have delayed for months and the withdrawal of theTanzanian along the borders, reluctant to "liberation" army. From June 1982, flee but deriving only marginal about one-third of those registering subsistence. Taking the last for settlement still came from inside drastic step, they arrive in the Uganda; the rest were those who transit centers weak and mal- had attempted to stay near the nourished. Many die awaiting border, hoping the situation would assistance in the planned reset. improve and they could return to tlement areas provided by Sudan their homes. Their delay was cata- and UNHCR. strophic. Thousands died of starva- tion, while trying to eke out a living along the overcrowded border. Hun- dreds more died of the effects of malnutrition, even after they had Thousands of Ugandan refugees entered settlements and were receiv- poured into the Sudan in 1982, most ing food rations. of them to Western Equatoria (the west bank of the Nile). The popula- For some, the situation in Uganda is tion of refugees in the planned set- confusing -there are so many con- tlements provided by the Sudan, tradictory reports. But for lzaruku which are supported by the United Ajaga, the facts were starkly clear Nations High Commissioner for Re- when on September 11 he came to fugees (UNHCR), shot up from 9,000 the UNHCR office in Yei to report in 3 settlements in March 1982 to that his brother and another relative 47,311 in 14 at the end of September. -

Amin: His Seizure and Rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1974 Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda. James Francis Hanlon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hanlon, James Francis, "Amin: his seizure and rule in Uganda." (1974). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2464. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2464 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS July 1974 Major Subject — Political Science AMIN: HIS SEIZURE AND RULE IN UGANDA A Thesis Presented By James Francis Hanlon Approved as to style and content by: Pro i . Edward E. Feit. Chairman of Committee Prof. Michael Ford, member ^ Prof. Ferenc Vali, Member /£ S J \ Dr. Glen Gordon, Chairman, Department of Political Science July 1974 CONTENTS Introduction I. Uganda: Physical History II. Ethnic Groups III. Society: Its Constituent Parts IV. Bureaucrats With Weapons A. Police B . Army V. Search For Unity A. Buganda vs, Ohote B. Ideology and Force vi. ArmPiglti^edhyithe-.Jiiternet Archive VII. Politics Without lil3 r 2Qj 5 (1970-72) VIII. Politics and Foreign Affairs IX. Politics of Amin: 1973-74 C one ius i on https://archive.org/details/aminhisseizureruOOhanl , INTRODUCTION The following is an exposition of Edward. -

2. Histories of Violence and Conflict

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Conflict legacies Understanding youth’s post-peace agreement practices in Yumbe, north-western Uganda Both, J.C. Publication date 2017 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Both, J. C. (2017). Conflict legacies: Understanding youth’s post-peace agreement practices in Yumbe, north-western Uganda. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 2. HISTORIES OF VIOLENCE AND CONFLICT INTRODUCTION In order to understand the legacies of past conflicts in present-day Yumbe, this chapter sketches the historical background of the people in a particular district as it emerges from the available literature and the oral histories and interviews I conducted. -

The Politics of Capitalist Enclosures in Nature Conservation: Governing Everyday Politics and Resistance in West Acholi, Northern Uganda

Global governance/politics, climate justice & agrarian/social justice: linkages and challenges An international colloquium 4‐5 February 2016 Colloquium Paper No. 50 The Politics of Capitalist Enclosures in Nature Conservation: Governing Everyday Politics and Resistance in West Acholi, Northern Uganda David Ross Olanya International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) Kortenaerkade 12, 2518AX The Hague, The Netherlands Organized jointly by: With funding assistance from: Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of organizers and funders of the colloquium. February, 2016 Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/ICAS_Agrarian https://twitter.com/TNInstitute https://twitter.com/peasant_journal Check regular updates via ICAS website: www.iss.nl/icas The Politics of Capitalist Enclosures in Nature Conservation: Governing Everyday Politics and Resistance in West Acholi, Northern Uganda David Ross Olanya Abstract This article examines the case of Appa village in the controversial East Madi Wildlife Reserve, how the people are attempting to resist and revoke their evictions by Uganda Wildlife Authority from the newly created Wildlife Game Reserve in 2002. This case analysis presents an important sites of struggle, illustrating the interplay of rationality [governing], everyday politics and political subjectivities. The legal and right-based practices of resisting only serve as interplays between governing and everyday politics through which the emerging subordinating groups is governed. This article presents how power produces resistance against capitalism and its enclosures. It is rooted in the notion that power produces resistance that are embodied in a particular actors or social groups emerging to challenge capitalist enclosures. -

COURSE OUTLINE PAPER 245/4 SECTION A: SEX, MARRIAGE and FAMILY (A) SEX A. Contents / Values of Sex Today B. African Traditional

` COURSE OUTLINE PAPER 245/4 SECTION A: SEX, MARRIAGE AND FAMILY (A) SEX a. Contents / values of sex today b. African traditional understanding of sex c. Sources of sex education In African traditional society [ways how sex education was transmitted in African traditional society] d. Importance of sex education in African tradition e. Sources of sex education in African tradition f. How the youth come to know about sex today g. Challenges parents and other elders in society face in trying to impart sex education to the youth h. Factors leading to permissiveness in society i. Characteristics / manifestations / indicators / signs of a permissive society j. How a Christian can help reduce the dangers of permissiveness k. Major cases of sex misuse in society l. Main causes of sex misuse m. Major impact of sex misuse n. Solutions to sex misuse o. Why there were limited cases of sex deviations In African traditional society (ATS) p. The general biblical teaching about sex CASE STUDIES OF SEX DEVIATIONS 1. Pre- marital sex (Fornication) (a) Causes and effects of fornication (b) How the girl- boy relationship should be stabilized (c) Solutions to fornication 2. Prostitution (a) Causes and dangers of prostitution (b) Cases of prostitution in the bible (c) Christian solutions to prostitution (d) Why prostitution should be legalized ` (e) Extent to which prostitution is a necessary evil 3. Rape and Defilement (a) Causes and impact (b) How to reduce rape and defilement (c) The role of the courts of law in promoting rape and defilement 4. Adultery (a) Causes and effects (b) Solutions to Adultery (c) Biblical teaching on Adultery 5. -

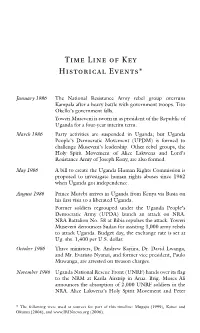

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

The Experience and Recollections from the Faculties, Schools, Institutes and Centres

8 The Experience and Recollections from the Faculties, Schools, Institutes and Centres Makerere’s Institute of Economics: New Programmes and a Contested Divorce The Harare-based African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), had been sponsoring a Masters degree in Economics, which taught African Economics at postgraduate level to assist African governments improve economic policy management for a number of years. McGill University in Montreal, Canada was running the programme for the English speaking African countries on behalf of the ACBF. However, after training a number of African economists at the university for some time, the ACBF was convinced that it made sense to transfer the training to Africa. McGill was not only expensive, it had another disadvantage: students studied in an alien environment, divorced from the realities of African economic problems. This necessitated a search for suitable universities in Anglophone Africa which had the capacity to host the programme. Acting on behalf of the ACBF, McGill University undertook a survey of universities in Anglophone Africa and identified two promising ones which met most of the conditions on ACBF’s checklist for hosting and servicing a regional programme of that kind. Earlier in 1996, Dr Apollinaire Ndorukwigira of the ACBF had visited Makerere to explore the possibility of Makerere participating in the new Economic Policy Management programme. On this particular visit, he said he was not making any commitments because McGill University was yet to undertake a detailed survey of a number of universities in Africa and, based on the findings, McGill University would advise the ACBF on the two most suitable universities which would host the programme.