Shaping the Choreography of Care & Support for Older People in Glasgow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stride with Pride Map FINAL Online Layout.Indd

LGBTQ+ people have been a part of Glasgow’s history as long as the city has existed. Although the histories of the LGBTQ+ community are often ignored or not recorded in traditional ways, we can find traces of their lives and experiences. From the court records of male sex workers in the Broomielaw to listings and adverts for club nights in the 2000s, and from memories of the saunas and club scenes of the 1980s to the direct action and activism of LGBTQ+ groups like the Lesbian Avengers. The terms we use now for LGBTQ+ people are vital reminder of the history of criminalisation modern definitions for experiences and identities in Scotland, and the impact it had on the that have always existed; when discussing any LGBTQ+ community. LGBTQ+ people in this map all efforts have been made to refer to people with the identities and While at Glasgow Green we’re also going pronouns they themselves used. to look at the story of New York politician (1) Murray Hall. Murray Hall was born in 1841 This map highlights just some of the people, in Govan, Glasgow, and died in 1901 in New places and spaces that have been a part of York. Hall emigrated to America in 1871 and STRIDE Glasgow’s LGBTQ+ heritage and history. It’s became a New York City bonds man and not exhaustive, but we have tried to make it as politician. He married twice and adopted a representative and inclusive of all LGBTQ+ people daughter with his second wife. After his death and experiences as possible within the limitations of breast cancer it was discovered that he had of the records available to us. -

Glasgow LGBT History Walk

Glasgow LGBT History Walk This walk was devised by OurStory Scotland in 2014 at the time of the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. The walk was led on 29 July by Donald Gray, Criz McCormick and Margaret Hamilton, and had input from many others, notably Tommy Clarke, Amy Murphy and Jeff Meek. In 2008, for the OurSpace exhibition at the Kelvingrove, the first LGBT exhibition at a major Scottish museum, OurStory Scotland created the OurSpace Map, mapping the past through places important to the LGBT community. Jeff Meek has created several LGBT Historical Maps of Scotland including an interactive Glasgow LGBT Historical Map that plots queer spaces and places that can be included along the way, or as detours from the route. The point of the History Walk is not to act as a guide to places that operate now, but to record a heritage of past places that have been significant for our community. This is a circular walk that can begin anywhere on the route, and of course can be walked in part or over several occasions. There is an extended loop out to the Mitchell Library. From there a diversion could be added to the Kelvingrove, site of the OurSpace exhibition in 2008. Another extended loop takes in the Citizens Theatre, People’s Palace and Glasgow Women’s Library. The extended loops can be omitted from a shorter central walk, or undertaken as separate walks. In July 2014, at the time of the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, the walk started and finished at Pride House. Route of the Glasgow LGBT History Walk 14 Albion Street Pride House for the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. -

Glasgow Attractions and Hotels

ATTRACTIONS 15 Glasgow Caledonian University 28 Hunterian Museum 43 Pollok House, Pollok Country Park 57 The Tenement House 16 Glasgow Cathedral 29 Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum 44 Provand’s Lordship 58 Theatre Royal 01 The Arches 17 Glasgow Central Mosque, Mosque Avenue 30 Kelvin Hall International Sports Arena 45 Rabbie’s Trail Burners Pick Up Point 59 Timberbush Tours 02 The Barony 18 Glasgow City Chambers 31 King’s Theatre 46 Ramshorn Theatre Pick Up Point 03 Botanic Gardens 19 Glasgow Film Theatre 32 The Lighthouse 47 Rangers Football Club, Edmiston Drive 60 Titan Crane, Clydebank 04 The Briggait 20 Glasgow Museums Resource Centre, 33 Loch Lomond Sealife Centre, Balloch 48 Riverside Museum 61 The Trades Hall of Glasgow 05 The Burrell Collection, Pollok Country Park South Nitshill 34 Loch Lomond Seaplanes Departure Point 49 Royal Scottish Academy of Music & Drama 62 Tron Theatre 06 Celtic Football Club, Kerrydale St 21 Glasgow Necropolis 35 Mackintosh Queen’s Cross Church 50 Scotland Street School Museum, 63 Trongate 103 07 Centre for Contemporary Arts 22 The Glasgow Royal Concert Hall 36 The Mitchell Library Scotland Street 64 University of Glasgow 08 Cineworld Cinema 23 The Glasgow School of Art 37 Mitchell Theatre & Moir Hall 51 Scottish Exhibition & Conference Centre 65 University of Strathclyde 09 Citizens Theatre, Gorbals Street 24 Glasgow Science Centre &Imax Cinema 38 The National Piping Centre 52 St Andrew’s in the Square 66 Waverley Excursions 10 City Halls & Old Fruitmarket 25 Hampden, Scotland’s National Stadium & 39 -

Handbook for Newcomers to Glasgow

Handbook for newcomers to Glasgow What is this document? This document contains a list of organisations and services that will be useful to anyone who has recently moved to Glasgow. These range from health services to community groups to legal aid. Until now, lists of this kind have only been available for a fee, making them inaccessible to some. This means that many new migrants to Glasgow struggle to access vital services. For this reason, we at Migrant Voice saw it as important to create an accessible platform for people to share and find these services. We hope this project makes it easier for newcomers to settle into the Glasgow community. This document was created by a group of Migrant Voice volunteers in Glasgow (listed below), many of whom have first-hand experience of moving to the city and trying to find their feet. Thank you to those volunteers and to Sofi Taylor, our Scotland trustee, who supported and mentored the volunteers on this activity. The list is a work in progress and we will continue to add relevant information as we find it. Equally, if you know of organisations or services that aren’t listed but should be, please write to us at [email protected] to let us know. Who is Migrant Voice? Migrant Voice is a migrant-led organisation working with migrants from all around the world with all kinds of status, including refugees and asylum seekers. We develop the media skills and confidence of migrants with the aim of strengthening their voices in the media and civil society in order to counter xenophobia and build support for our rights. -

Festival 2014 Highlights

Today’s Highlights Friday 1 August 2014 Events Key: • Comedy • Film • Literature and • Theatre • Dance and • Gaelic Spoken Word • Visual Arts Physical Theatre • LGBT • Music • Exhibition • Family • Sporting Event • Talks Glasgow Green Live Zone Living Room Back Garden • The Ha Orchestra 12noon to 12.45pm Try out lots of sports, including athletics, cycling, hockey, • Soweto Spiritual Singers 1.30pm to 2.15pm judo and table tennis with Glasgow Sport. Explore how your body works with interactive exhibits from Glasgow Science • Clinton Fearon Band 3.00pm to 4.00pm Centre. Have fun and learn new skills playing traditional • Sierra Leone Refugee All Stars 5.00pm to 6.00pm games from the Commonwealth with UNICEF. • Kobo Town 6.45pm to 7.45pm • Maxi Priest 8.55pm to 9.55pm The Shed The Shed is a friendly place for creating your own imaginative crafts and browsing the works of Scotland-based Playhouse designers and makers. It includes the workshop space in the Creativity Hothouse and the Big Draw Greenhouse. • Stories of Scotland and the Caribbean 11.00am to 12noon Please sign up in advance for workshops. • Have a go... Carnival Dance 1.00pm to 3.00pm • Unoma Ukudo and Band 4.00pm to 4.45pm • Glasgow School of Art - Color Hotel 11.00am to 4.00pm • Glasgow and the Caribbean: 5.30pm to 6.30pm Slavery and Emancipation Discussion • Calypso Rose & Band 7.15pm to 8.30pm Creativity Hothouse • O-Pin - Recycled Fabric Jewellery 11.00am to 1.00pm Making Workshop The Kitchen • O-Pin - Recycled Wood Jewellery 2.00pm to 4.00pm Scotland is a land of food and drink, blessed with world- Making Workshop class produce, so visit The Kitchen to enjoy hot smoked salmon rolls, gourmet burgers, sushi and wood-fired pizza alongside • O-Pin - Pin and Brooch 5.00pm to 7.00pm favourites like haggis, neeps and tatties. -

2Nd Glasgow Scout Group

2ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 71 GLENCAIRN DRIVE GLASGOW G414PN 100% 30TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 37 LAMMERMOOR AVENUE GLASGOW G523BE 100% 360 DEGREES FINANCE LTD 40 WASHINGTON STREET GLASGOW G38AZ 100% 360CRM LTD 80 ST VINCENT STREET GLASGOW 25% 3RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 121 SHAWMOSS ROAD GLASGOW G414AE 100% 43RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 4 HOLMHEAD ROAD GLASGOW G443AS 100% 4C DESIGN LIMITED 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 4C DESIGN LTD 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 50TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 23 GARRY STREET GLASGOW G444AZ 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 7 SEATER CENTRE (SCOTLAND) LTD 1152 TOLLCROSS ROAD GLASGOW G328HE 100% 72ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 500 A CROW ROAD GLASGOW G117DW 100% 86TH/191 GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 79 SANDA STREET GLASGOW G208PT 100% 965 LTD 965 DUKE STREET GLASGOW 100% 9TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 99 THORNWOOD PLACE GLASGOW 100% A & E BROWN (PLUMBERS MERCHANTS) LTD 1320 SPRINGBURN ROAD GLASGOW G211UT 25% A & F MCKINNON LTD 391 VICTORIA ROAD GLASGOW G428RZ 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A& L LTD 12 PLEAN STREET GLASGOW G140YH 25% A & M TRAINING LTD 28 ADAMSWELL STREET GLASGOW 100% A & P MACINTYRE LTD 213 CLARKSTON ROAD GLASGOW G443DS 25% A A MENZIES & CO 180 QUEEN MARGARET DRIVE GLASGOW G208NX 100% A A MOTORS LTD 7 MORDAUNT STREET GLASGOW 50% A ALEXANDER & SON (ELECTRICAL) LTD 9 CATHKINVIEW ROAD GLASGOW G429EH 25% A ALEXANDER & SON(ELECTRICAL) LTD 24 LOCHLEVEN ROAD GLASGOW G429JU 100% A B FRAMING -

The Lighthouse, 11 Mitchell Lane, Glasgow, G1 3NU

The Lighthouse, 11 Mitchell Lane, Glasgow, G1 3NU Tel: 0141 276 5365 Email: [email protected] Website: www.thelighthouse.co.uk Contents VISIT – WHAT TO SEE AT A GLANCE ................................................. - 2 - ABOUT US ............................................................................................ - 3 - GETTING HERE .................................................................................... - 5 - ON ARRIVAL ......................................................................................... - 6 - WHEELCHAIR USERS/BUGGIES/LUGGAGE ...................................... - 9 - PRE ARRIVAL ..................................................................................... - 11 - ARRIVAL ............................................................................................. - 12 - EXHIBITIONS ...................................................................................... - 13 - MACKINTOSH CENTRE ..................................................................... - 15 - TOURS ................................................................................................ - 17 - DOOCOT CAFE .................................................................................. - 18 - FLOOR PLAN ...................................................................................... - 19 - ESSENTIAL INFORMATION ............................................................... - 19 - VIRTUAL TOUR ................................................................................. -

Consulting, Transportation

Proposed Mixed-Use Development, Plot A, Candleriggs, Glasgow Transport Statement October 2019 Proposed Mixed Use Development, Candleriggs, Glasgow - Transport Assessment 133416 – Plot TS CONTROL SHEET CLIENT: Candleriggs Developments 2 Ltd PROJECT TITLE: Proposed Mixed Use Development, Candleriggs, Glasgow REPORT TITLE: Transport Statement PROJECT REFERENCE: 133416 DOCUMENT NUMBER: 133416 / PLOT A TS Issue and Approval Schedule: ISSUE 1 Name Signature Date Prepared by J Craft Signed copy held on file 28/10/2019 Reviewed by R McDonald Signed copy held on file 28/10/2019 Approved by R McDonald Signed copy held on file 28/10/2019 Issue Details FINAL Revision Record: Issue Date Status Description By Chk App 2 30/10/19 Final Amended for client comments JC RMcD RMcD This document has been prepared in accordance with procedure OP/P02 of the Fairhurst Quality and Environmental Management System Proposed Mixed Use Development, Plot A Candleriggs, Glasgow - Transport Assessment 133416 – Plot A TS This document has been prepared in accordance with the instructions of the client,Candleriggs Developments 2 Ltd, for the client’s sole and specific use. Any other persons who use any information contained herein do so at their own risk. Proposed Mixed Use Development, Plot A Candleriggs, Glasgow - Transport Assessment 133416 – Plot A TS Contents 1 Introduction ________________________________________________________________________ 1 General 1 Site location 1 Consultation 2 Planning Policy Context and Guidance 2 Report Structure 2 2 Existing Site and -

Glasgow’S Architecture and Built Heritage

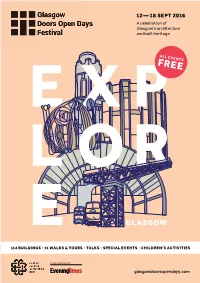

12 — 18 SEPT 2016 A celebration of Glasgow’s architecture and built heritage ALL EVENTS FREE GLASGOW 114 BUILDINGS • 51 WALKS & TOUrs • TALKS • SPECIAL EVENTS • CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES In association with: glasgowdoorsopendays.com THINGS TO KNOW Details in this brochure were correct at the time of going to print, PHOTOGRAPHY but the programme is subject to change. For updates please check COMPETITION WIN glasgowdoorsopendays.com, sign up to PRIZES! H E our e-bulletin and follow our social media. GlasgowDoorsOpenDays GlasgowDOD GlasgowDoorsOpenDays TIMINGS Check individual listings for opening hours and event times. Send us your photos of AccESS L L O Due to their historic or unique nature, Doors Open Days 2016 we regret that some venues are not fully accessible. Access is indicated in each and win some fantastic listing and in more detail on our website. prizes! FOR THE faMILY Glasgow Doors Open Days is The majority of buildings and events are fun for children and we’ve highlighted back for the 27th year, celebrating key family activities on page 34. We’ve CATEGORIES also put together a dedicated children’s Inspired by Mackintosh | People and Place | Glasgow’s unique architecture programme which will be distributed to Architectural Detail | Cityscape | Behind the Scenes and built heritage! This year Glasgow primary schools in late August. YOU COULD WIN VOLUNTEERS – £250 voucher to spend at Glasgow Architectural Salvage we’re part of the national Festival Doors Open Days is made possible – A year’s subscription to Scots Heritage Magazine -

Today's Highlights Saturday 2 August 2014

Today’s Highlights Saturday 2 August 2014 Events Key: • Comedy • Family • LGBT • Music • Dance and • Film • Literature and • Sporting Event Physical Theatre • Gaelic Spoken Word • Theatre • Visual Arts Glasgow Green Live Zone Glasgow Mix Tape, curated by Chemikal Underground Living Room The Shed • Sydney Devine 12.45pm to 1.15pm The Shed is a friendly place for creating your own imaginative • Holy Mountain 1.45pm to 2.15pm crafts and browsing the works of Scotland-based designers and makers. It includes the workshop space in the Creativity Hothouse • Errors 2.45pm to 3.15pm and the Big Draw Greenhouse. Please sign up in advance for • Malcolm Middleton 3.45pm to 4.15pm workshops. • The Bluebells 5.15pm to 5.45pm • The Phantom Band 6.15pm to 7.00pm Creativity Hothouse • Admiral Fallow 7.30pm to 8.15pm • O-Pin - Medal-making Workshops 11.00am to 12noon • Lloyd Cole 8.45pm to 9.30pm • O-Pin - Medal-making Workshops 12noon to 1.00pm • O-Pin - Medal-making Workshops 2.00pm to 3.00pm Playhouse • O-Pin - Medal-making Workshops 3.00pm to 4.00pm • Penman Jazzmen 11.00am to 12.30pm • O-Pin Project - Pin and Brooch 3.00pm to 4.00pm • Trembling Bells 1.30pm to 2.00pm Making workshop • Richard Youngs 2.30pm to 3.00pm • O-Pin Project - Pin and Brooch 3.00pm to 4.00pm • Alarm Bells 3.30pm to 4.00pm Making workshop • Ubre Blanca 4.30pm to 5.00pm • Bis 5.30pm to 6.00pm The Kitchen Edwyn Collins 6.30pm to 7.15pm • Scotland is a land of food and drink, blessed with world-class • The Amphetameanies 7.45pm to 8.30pm produce, so visit The Kitchen to enjoy hot smoked salmon rolls, gourmet burgers, sushi and wood-fired pizza alongside Back Garden favourites like haggis, neeps and tatties. -

MERCHANT CITY Candleriggs Square

MERCHANT CITY Candleriggs Square Planning Permission Stage 2 Consultation 01_Introduction Background Information This Public Consultation Event was organised to support three Proposal of Application Notices (PANs) submitted to Glasgow City Council for the redevelopment of Candleriggs Square, in the heart of Glasgow’s Merchant City. Candleriggs Square is the gap site bound by Hutcheson Street, Trongate, Candleriggs and Wilson Street (see map(s) below). This presentation for the applications for Planning Permission represents the first stage in the consultation process. Once detailed proposals are more advanced, an additional consultation event relating to the detailed plans for the site will be held on 8 October. These are likely to be presented in 3 individual phases of development, and separate planning applications will be lodged for each phase. The developer is Candleriggs Development 2 Ltd, a joint venture between Drum Property Group and Stamford Property Investments. Drum Property Group Drum Property Group is an award-winning property development and investment company with a long track record of successful trading and growth. Drum Property Group is active throughout the UK and engaged in a broad range of projects covering a variety of sectors including residential, business space, retail, industrial and leisure. In Glasgow, Drum is currently developing the residential and office quarter at Buchanan Wharf, on the river Clyde, and the G3 Square apartment complex in Finnieston. Stamford Property Investments Stamford Property Holdings and its subsidiaries are a multi- faceted property developer specialising in private residential, PRS and student accommodation. Stamford has a strong track record of institutional grade developments in major cities in the UK. -

The Town Plans of Glasgow, 1764 - 1865: a History and Cartobibliography

THE TOWN PLANS OF GLASGOW, 1764 - 1865: A HISTORY AND CARTOBIBLIOGRAPHY JOHN N. MOORE A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Glasgow for the degree of Master of Letters. Department of Geography, University of Glasgow March, 1994 Copyright (c) John N. Moore, 1994. ProQuest Number: 13818432 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818432 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 J l o qs S3 ) GLASGOW u n i v e r s i t y u b r a r y 2 ABSTRACT This thesis lists and considers all of the town plans which depict the City of Glasgow up to and including the large scale maps produced by the Ordnance Survey. Earlier depictions of town layout are of great value in an interpretation of urban patterns and their development but their use needs to be based on an understanding of their original purpose, the ability of the cartographer and their correct dating. In the past, many false assumptions have been made about such documents and this research seeks to correct many of these.