Working Paper 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

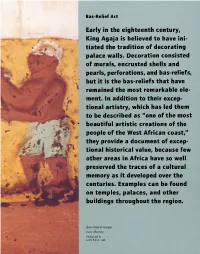

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

Les 6 Articles Du BRAB N° 48 Juin 2005

Bulletin de la Recherche Agronomique du Bénin Numéro 48 – Juin 2005 Identification et caractérisation des stations forestières pour un aménagement durable de la forêt classée de Toffo (Département du plateau ; sud–est du Bénin) O. S. N. L. DOSSA 10 , C. J. GANGLO 10 , V. ADJAKIDJÈ 11 , E. AGBOSSOU 10 et B. DE FOUCAULT 12 Résumé L’étude s’est déroulée dans la forêt classée de Toffo située entre 6°59’-7°01’ lat. Nord et 2°37-2°39’ long. Est. Elle a pour objectif d’asseoir les bases d’un aménagement et d’une gestion durable de la forêt. La végétation a été étudiée suivant l’approche synusiale ; les facteurs écologiques à travers la mesure des pentes, l’appréciation de la texture tactile, la description des profils pédologiques complétée par des analyses d’échantillons de sol au laboratoire. Les paramètres dendrométriques ont été mesurés dans des placettes circulaires de 14 m de rayon pour la forêt naturelle et de 10 m de rayon pour les plantations. Au total 16 synusies végétales ont été identifiées et intégrées en six phytocoenoses dont deux pionnières et quatre non pionnières. Des mesures d’aménagement ont été proposées à chacune des quatre stations forestières correspondant aux biotopes des phytocoenoses non pionnières. Mots clés : phytosociologie, stations forestières, aménagement, Toffo, Bénin. Identification and characterization of forest sites for sustainable management of Toffo forest reserve (Plateau Department ; south-east Benin) Abstract The study has been done in Toffo forest reserve (6°59-7°01’of North latitude and 2°37’-2°39’ of East longitude). Its purpose is to yield data on phytodiversity to help sustainable management of the forest. -

GIEWS Country Brief Benin

GIEWS Country Brief Benin Reference Date: 23-April-2020 FOOD SECURITY SNAPSHOT Planting of 2020 main season maize ongoing in south under normal moisture conditions Above-average 2019 cereal crop harvested Prices of coarse grains overall stable in March Pockets of food insecurity persist Start of 2020 cropping season in south follows timely onset of rains Following the timely onset of seasonal rains in the south, planting of yams was completed in March, while planting of the main season maize crop is ongoing and will be completed by the end of April. The harvest of yams is expected to start in July, while harvesting operations of maize will start in August. Planting of rice crops, to be harvested from August, is underway. The cumulative rainfall amounts since early March have been average to above average in most planted areas and supported the development of yams and maize crops, which are at sprouting, seedling and tillering stages. Weeding activities are normally taking place in most cropped areas. In the north, seasonal dry weather conditions are still prevailing and planting operations for millet and sorghum, to be harvested from October, are expected to begin in May-June with the onset of the rains. In April, despite the ongoing pastoral lean season, forage availability was overall satisfactory in the main grazing areas of the country. The seasonal movement of domestic livestock, returning from the south to the north, started in early March following the normal onset of the rains in the south. The animal health situation is generally good and stable, with just some localized outbreaks of seasonal diseases, including Trypanosomiasis and Contagious Bovine Peripneumonia. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Online Appendix to “Can Informed Public Deliberation Overcome Clientelism? Experimental Evidence from Benin”

Online Appendix to “Can Informed Public Deliberation Overcome Clientelism? Experimental Evidence from Benin” by Thomas Fujiwara and Leonard Wantchekon 1. List of Sample Villages Table A1 provides a list of sample villages, with their experimental and dominant can- didates. 2. Results by Commune/Stratum Table A2.1-A2.3 presents the results by individual commune/stratum. 3. Survey Questions and the Clientelism Index Table A3.1 provides the estimates for each individual component of the clientelism index, while Table A3.2 details the questions used in the index. 4. Treatment Effects on Candidate Vote Shares Table A4 provides the treatment effect on each individual candidate vote share. 5. Estimates Excluding Communes where Yayi is the EC Table A5 reports results from estimations that drop the six communes where Yayi is the EC. Panel A provides estimates analogous from those of Table 2, while Panels B and C report estimates that are similar to those of Table 3. The point estimates are remarkably similar to the original ones, even though half the sample has been dropped (which explains why some have a slight reduction in significance). 1 6. Estimates Including the Commune of Toffo Due to missing survey data, all the estimates presented in the main paper exclude the commune of Toffo, the only one where Amoussou is the EC. However, electoral data for this commune is available. This allows us to re-estimate the electoral data-based treatment effects including the commune. Table A6.1 re-estimates the results presented on Panel B of Table 2. The qualitative results remain the same. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

The House of Oduduwa: an Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa

The House of Oduduwa: An Archaeological Study of Economy and Kingship in the Savè Hills of West Africa by Andrew W. Gurstelle A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Carla M. Sinopoli, Chair Professor Joyce Marcus Professor Raymond A. Silverman Professor Henry T. Wright © Andrew W. Gurstelle 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I must first and foremost acknowledge the people of the Savè hills that contributed their time, knowledge, and energies. Completing this dissertation would not have been possible without their support. In particular, I wish to thank Ọba Adétùtú Onishabe, Oyedekpo II Ọla- Amùṣù, and the many balè,̣ balé, and balọdè ̣that welcomed us to their communities and facilitated our research. I also thank the many land owners that allowed us access to archaeological sites, and the farmers, herders, hunters, fishers, traders, and historians that spoke with us and answered our questions about the Savè hills landscape and the past. This dissertion was truly an effort of the entire community. It is difficult to express the depth of my gratitude for my Béninese collaborators. Simon Agani was with me every step of the way. His passion for Shabe history inspired me, and I am happy to have provided the research support for him to finish his research. Nestor Labiyi provided support during crucial periods of excavation. As with Simon, I am very happy that our research interests complemented and reinforced one another’s. Working with Travis Williams provided a fresh perspective on field methods and strategies when it was needed most. -

Monographie Des Communes Des Départements De L'atlantique Et Du Li

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des communes des départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 2 Tables des matières LISTE DES CARTES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS DE L’ATLANTIQUE ET DU LITTORAL ................................................ 7 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LE DEPARTEMENT DE L’ATLANTIQUE ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1.1. Présentation du Département de l’Atlantique ...................................................................................... -

Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa)

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver II || June 2018 || PP 33-39 Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa) Léocadie Odoulami, Brice S. Dansou & Nadège Kpoha Laboratoire Pierre PAGNEY, Climat, Eau, Ecosystème et Développement LACEEDE)/DGAT/FLASH/ Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC). 03BP: 1122 Cotonou, République du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) Corresponding Auther: Léocadie Odoulami Summary :The population of the common Za-kpota is subjected to several difficulties bound at the access to the drinking water. This survey aims to identify and to analyze the problems of provision in drinking water and the risks on the human health in the township of Za-kpota. The data on the sources of provision in drinking water in the locality, the hydraulic infrastructures and the state of health of the populations of 2000 to 2012 have been collected then completed by information gotten by selected 198 households while taking into account the provision difficulties in water of consumption in the households. The analysis of the results gotten watch that 43 % of the investigation households consume the water of well, 47 % the water of cistern, 6 % the water of boring, 3% the water of the Soneb and 1% the water of marsh. However, the physic-chemical and bacteriological analyses of 11 samples of water of well and boring revealed that the physic-chemical and bacteriological parameters are superior to the norms admitted by Benin. The consumption of these waters exposes the health of the populations to the water illnesses as the gastroenteritis, the diarrheas, the affections dermatologic,.. -

Plant Communities, Forest Site Identification and Classification In

BOIS ET FORÊTS DES TROPIQUES, 2006, N° 288 (2) 25 GROUPEMENTS VÉGÉTAUX / LE POINT SUR… Plant communities, forest site identification Jean Cossi Ganglo1 Bruno de Foucault2 and classification in Toffo 1 University of Benin, Faculty reserve, South-Benin of Agronomy Department of Environmental Management BP 1493 Calavi Republic of Benin 2 Department of Botany Faculty of Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences BP 83, 59006 Lille Cedex France Nine plant communities in Toffo forest reserve (southern Benin) were identified by using a phytosociological approach. Within each non-pioneer plant community, site conditions and productivity levels were remarkably homogenous. The relationships between plant communities, ecological factors and plantation productivity were used to identify and map five forest sites, for which management specifications are indicated. Chromolaera odorata plant community Photo J. C. Ganglo. 26 BOIS ET FORÊTS DES TROPIQUES, 2006, N° 288 (2) FOCUS / PLANT COMMUNITIES Jean Cossi Ganglo, Bruno de Foucault RÉSUMÉ ABSTRACT RESUMEN GROUPEMENTS VÉGÉTAUX, PLANT COMMUNITIES, FOREST SITE AGRUPACIONES VEGETALES, IDENTIFICATION ET CLASSEMENT IDENTIFICATION AND CLASSIFICATION IDENTIFICACIÓN Y CLASIFICACIÓN DES STATIONS FORESTIÈRES DANS IN TOFFO RESERVE, SOUTHERN BENIN DE LAS ESTACIONES EN LA RESERVA LA RÉSERVE DE TOFFO, SUD-BÉNIN DE TOFFO, SUR DE BENÍN. Des études phytosociologiques ont Phytosociological surveys were car- Se efectuaron estudios fitosociológi- été faites, entre novembre 2001 et ried out from November 2001 to cos, entre noviembre de 2001 y marzo mars 2004, dans la forêt de Toffo March 2004 in Toffo forest reserve de 2004, en el bosque de Toffo (6° 51’ - 6° 53’ latitude nord et 2° 05’ (latitude N 6° 51’ - 6° 53’ to longitude (6° 51’ - 6° 53’ N y 2° 05’ - 2° 10’ E), - 2° 10’ longitude est), au Sud-Bénin E 2° 05’ - 2° 10’) in southern Benin en el Benín meridional (África occi- (Afrique de l’Ouest), en vue d’identi- (West Africa), in order to identify and dental) para identificar y clasificar las fier et de classer les stations fores- classify forest sites. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

(DMPA-SC) in Benin

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Introduction of Community-Based Provision of Subcutaneous Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA-SC) in Benin: Programmatic Results Tishina Okegbe,a Jean Affo,b Florence Djihoun,b Alexis Zannou,b Odilon Hounyo,b Gaston Ahounou,c Karamatou Adegnika Bangbola,c Nancy Harrisd Lay community health workers and facility-based health care providers in Benin were trained to administer DMPA-SC safely and effectively in 10 health zones. Community-based DMPA-SC was popular, particularly among new users of contraception, and could help the country achieve its family planning goals. Résumé en français à la fin de l'article. ABSTRACT The Republic of Benin faces high maternal, newborn, and child mortality; low modern contraceptive use; and a critical shortage of health workers. In 2013, the Government of Benin made 3 reproductive health commitments to improve national health indicators, in- cluding expanding provision of family planning services at the community level through task sharing. Since 2016, the Advancing Partners & Communities (APC) project has been helping the Benin Ministry of Health (MOH) provide subcutaneous depot medroxypro- gesterone acetate (DMPA-SC; brand name Sayana Press) through facility-based health care providers and community health workers known as relais communautaires (RCs). DMPA-SC is an easy-to-administer, discreet injectable contraceptive that provides 3 months of protection from pregnancy. Beginning in May 2017, the government introduced DMPA-SC through a phased approach in 10 health zones, which encompassed 149 health centers and 614 villages. Between June 2017 and June 2018, the MOH and APC trained 278 facility-based providers and 917 RCs to provide DMPA-SC, and nearly 11,000 doses were subsequently administered to 7,997 women at facilities and in communities.