Hellman Warren 2014.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

1 DICKSON LEW LOUIE Office: 510-352-8885 Mobile: 510-384-4229 [email protected] [email protected] May 4, 2020

DICKSON LEW LOUIE Office: 510-352-8885 Mobile: 510-384-4229 [email protected] [email protected] May 4, 2020 PROFESSIONAL/ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of California, Davis (2012- present] - Lecturer/Visiting Assistant Professor of Management San Francisco State University (2015-present) - Lecturer, Executive MBA Program, College of Business Time Capsule Press, LLC (2008-present) - President and CEO Louie & Associates (1999-present) - Principal The ClearLake Group (2012-18) - Colleague San Francisco Chronicle (2002-2006) - Strategic Planning Director (newsroom) (2003-06) - Advertising Business Manager (2002-03) San Jose Mercury News (1998-1999) - Business Development and Planning Manager (1998-99) - Advertising Business Manager (1998) Harvard Business School, Harvard University (1996-98) - Research Associate Los Angeles Times/Times Mirror Company (1983-95) - Corporate Financial Planning Manager, Times Mirror Newspaper Group, (1994-95) - Circulation Planning Manager, Los Angeles Times (1989-1994) - Senior Financial Planning Analyst, Los Angeles Times (1988-1999) - Financial Planning Analyst, Los Angeles Times (1984-88) - Financial Planning Intern, Los Angeles Times (1983) California State University, Hayward (Summer 1984) - Lecturer, Department of Accounting 1 Arthur Young & Company, CPAs (1980-82- Staff auditor and tax accountant, San Francisco Office (1980-82) EDUCATION University of Chicago, MBA, Marketing, Finance, and Statistics, 1984. California State University, Hayward, BS, Business Administration (Accounting option), minor, Mass Communications (Journalism), with high honors, 1980. EXECUTIVE EDUCATION Building and Leveraging Brand Equity, Wharton School of Commerce, University of Pennsylvania, May 1996. Leading Product Development, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, June 1997. Executive Leadership Program, Media Management Institute, Kellogg School of Management and Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University, Spring 2002. Disney Institute, Disney’s Approach to Leadership Excellence, Disneyland, Anaheim, California, July 2017. -

Spooky Trades/Corporate Fraud an Introduction to Corporate Scandals Brainteaser Problem

Spooky Trades/Corporate Fraud An introduction to corporate scandals Brainteaser Problem: You and I are to play a competitive game. We shall take it in turns to call out integers. The first person to call out '50' wins. The rules are as follows: –The player who starts must call out an integer between 1 and 10, inclusive; –A new number called out must exceed the most recent number called by at least one and by no more than 10. (if first number is 5, the next number can be anything 6 to 15) Do you want to go first, and if so, what is your strategy? Brainteaser Solution: • Winning number must be just out of reach of other player • 50 -> 39 -> 28 -> 17 -> 6 Market Update • Eurozone - draghi came out with a more dovish tilt on the announcement regarding their QE program • Fed – Chairman still up in the air, but Powell is expected as of now • 19th party congress – People looking at to see what will happen with China going forward Fraud What is fraud? Death Arbitrage • Initially designed as an estate planning tool • If one joint-owner dies, the other is able to redeem the bond at par • Death put option on bonds + terminally ill patients = arbitrage • Banks would get mad and refuse to redeem to a hedge fund • “Fair exploit of a wall street loophole” Ponzi Scheme • Old investors are (falsely) told about great returns, while new investors’ capital is used to fulfill old investors’ capital withdrawals as needed • Essentially robbing Friend A to pay Friend B • Works until the money runs out Original Ponzi Scheme • Named after Charles Ponzi for his postal stamp arbitrage • Buy stamps cheap in Italy and exchange them for a higher value in the U.S. -

Oral History with Paul J. Ferri

Oral History with Paul J. Ferri NVCA-Venture Forward Oral History Collection This oral history is part of NVCA-Forward Oral History Collection at the Computer History Museum and was recorded under the auspieces of the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA). In October 2018, the NVCA transferred the copyright of this oral history to the Computer History Museum to ensure that it is freely accessible to the public and preserved for future generations CHM Reference number: X8628.2018 © 2021 Computer History Museum National Venture Capital Association Venture Capital Oral History Project PAUL J. FERRI Interview Conducted by Carole Kolker, PhD November 28, 2012 December 6, 2012 This collection of interviews, Venture Capital Greats, recognizes the contributions of individuals who have followed in the footsteps of early venture capital pioneers such as Andrew Mellon and Laurance Rockefeller, J. H. Whitney and Georges Doriot, and the mid-century associations of Draper, Gaither & Anderson and Davis & Rock — families and firms who financed advanced technologies and built iconic US companies. Each interviewee was asked to reflect on his formative years, his career path, and the subsequent challenges faced as a venture capitalist. Their stories reveal passion and judgment, risk and rewards, and suggest in a variety of ways what the small venture capital industry has contributed to the American economy. As the venture capital industry prepares for a new market reality in the early years of the 21st century, the National Venture Capital Association reports (2008) that venture capital investments represented 21 percent of US GDP and were responsible for 12.1 million American jobs and 2.9 trillion in sales. -

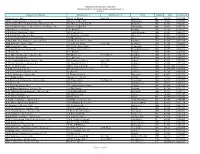

Agencie Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip License

Massachusettes Division of Insurance Massachusetts Licensed Property and Casualty Agencies 9/1/2011 Agencie Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip License 12 Interactive, LLC 224 West Huron Suite 6E Chicago IL 60654 1880124 20th Century Insurance Services,Inc 3 Beaver Valley Rd Wilmington DE 19803 1846952 21st Century Benefit & Insurance Brokerage, Inc. 888 Worcester St Ste 80 Wellesley MA 02482 1782664 21st Century Insurance And Financial Services, Inc. 3 Beaver Valley Rd Wilmington DE 19803 1805771 21st Insurance Agency P.O. Box 477 Knoxville TN 37901 1878897 A & K Fowler Insurance,LLC 200 Park Street North Reading MA 01864 1805577 A & P Insurance Agency,Inc. 273 Southwest Cutoff Worcester MA 01604 1780999 A .James Lynch Insurance Agency,Inc. 297 Broadway Lynn MA 019041857 1781698 A Plus Blue Lion Insurance Agency, LLC. 1324 Belmont Street Suite Brockton MA 02301 1887320 A&B Insurance Group, LLC 239 Littleton Road Suite 4B Westford MA 01886 1856659 A&R Associates, Ltd. 6379 Little River Tnpk Alexandria VA 22312 1847232 A. Action Insurance Agency Inc 173 West Center Street West Bridgewater MA 02379 1898416 A. B. Gile, Inc. P.O. Box 66 Hanover NH 03755 1842909 A. F. Macedo Insurance Agency, Inc. 646 Broadway P. O. Box C Raynham MA 02767 1781769 A. Gange & Sons, Inc. P.O. Box 301 Medford MA 02155 1780731 A. M. Franklin Insurance Agency, Inc. 300 Congress Street Ste. 308 Quincy MA 02169 1878527 A. Regan Insurance Agency, Inc. 213 Broadway Street (Rear) Methuen MA 01844 1872103 A. W. G. Dewar, Inc. 4 Batterymarch Park Ste 320 Quincy MA 021697468 1780211 A.A.Dority Company, Inc. -

LACERS Los Angeles City Employees’ Retirement System

LACERS Los Angeles City Employees’ Retirement System Report to Board of Administration Agenda of: AUGUST 3, 2009 From: Daniel P. Gallagher, Chief Investment Officer ITEM: V−A SUBJECT: NOTIFICATION OF UP TO $20 MILLION INVESTMENT IN HELLMAN & FRIEDMAN CAPITAL PARTNERS VII, L.P. Recommendation: That the Board receive and file this notice. Discussion: Attached is an investment abstract for Hellman & Friedman Capital Partners VII, L.P. (H&F VII) prepared by Hamilton Lane, LACERS’ traditional alternative investments consultant. Background H&F VII (Fund) is projected to be a $7 billion, hard cap $10 billion, middle-market to large cap buyout fund focusing on a variety of industries, including financial services, media, software/data services, business services, healthcare, internet/digital media, and energy/industrials. Investments will be pursued both in the U.S. and Western Europe with a small percentage that can be invested in Eastern Europe, Asia and Australia. LACERS has invested $31 million in H&F Funds with $11 million in H&F V (vintage 2004), and $20 million in H&F VI (vintage 2007). The General Partner (GP), founded in 1987 by Warren Hellman and Tully Friedman, has an experienced team. The majority of team members have worked and invested successfully together over many years and through several economic and private equity market cycles. H&F VII will be managed by senior partners Warren Hellman, Brian Powers, Philip Hammarskjold, Patrick Healy, and Thomas Steyer. The principals average over twenty-three years private equity experience and seventeen years tenure with the GP. They will be supported by thirty-one additional investment professionals and forty-one support staff. -

Reportto the Community

REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY Public Broadcasting for Greater Washington FISCAL YEAR 2020 | JULY 1, 2019 – JUNE 30, 2020 Serving WETA reaches 1.6 million adults per week via local content platforms the Public Dear Friends, Now more than ever, WETA is a vital resource to audiences in Greater THE WETA MISSION in a Time Washington and around the nation. This year, with the onset of the Covid-19 is to produce and hours pandemic, our community and our country were in need. As the flagship 1,200 distribute content of of new national WETA programming public media station in the nation’s capital, WETA embraced its critical role, of Need responding with enormous determination and dynamism. We adapted quickly intellectual integrity to reinvent our work and how we achieve it, overcoming myriad challenges as and cultural merit using we pursued our mission of service. a broad range of media 4 billion minutes The American people deserved and expected information they could rely to reach audiences both of watch time on the PBS NewsHour on. WETA delivered a wealth of meaningful content via multiple media in our community and platforms. Amid the unfolding global crisis and roiling U.S. politics, our YouTube channel nationwide. We leverage acclaimed news and public affairs productions provided trusted reporting and essential context to the public. our collective resources to extend our impact. of weekly at-home learning Despite closures of local schools, children needed to keep learning. WETA 30 hours programs for local students delivered critical educational resources to our community. We significantly We will be true to our expanded our content offerings to provide access to a wide array of at-home values; and we respect learning assets — on air and online — in support of students, educators diversity of views, and families. -

Color Front Cover

COLOR FRONT COVER COLOR CGOTH IS I COLOR CGOTH IS II COLOR CONCERT SERIES Welcome to our 18th Season! In this catalog you will find a year's worth of activities that will enrich your life. Common Ground on the Hill is a traditional, roots-based music and arts organization founded in 1994, offering quality learning experiences with master musicians, artists, dancers, writers, filmmakers and educators while exploring cultural diversity in search of a common ground among ethnic, gender, age, and racial groups. The Baltimore Sun has compared Common Ground on the Hill to the Chautauqua and Lyceum movements, precursors to this exciting program. Our world is one of immense diversity. As we explore and celebrate this diversity, we find that what we have in common with one another far outweighs our differences. Our common ground is our humanity, often best expressed by artistic traditions that have enriched human experience through the ages. We invite you to join us in searching for common ground as we assemble around the belief that we can improve ourselves and our world by searching for the common ground in one another, through our artistic traditions. In a world filled with divisive, negative news, we seek to discover, create and celebrate good news. How we have grown! Common Ground on the Hill is a multifaceted year-round program, including two separate Traditions Weeks of summer classes, concerts and activities, held on the campus of McDaniel College, two separate Music and Arts festivals held at the Carroll County Farm Museum, two seven-event Monthly Concert Series held in Westminster and Baltimore, and a new program this summer at the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, Common Ground on Seminary Ridge. -

Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit

ASSOCIATED PRESS/J. S PRESS/J. ASSOCIATED cott A PP L E WH ITE Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit Roger Altman, William Daley, John Podesta, Robert Rubin, Leslie Samuels, Lawrence Summers, Neera Tanden, and Antonio Weiss with Michael Ettlinger, Seth Hanlon, Michael Linden December 2012 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Reforming Our Tax System, Reducing Our Deficit Roger Altman, William Daley, John Podesta, Robert Rubin, Leslie Samuels, Lawrence Summers, Neera Tanden, and Antonio Weiss with Michael Ettlinger, Seth Hanlon, Michael Linden December 2012 Note from the authors: As in any collaborative process, there has been much give and take among the participants in developing this final product. We all subscribe to the analysis and principles articulated here, to the need for revenue levels at the level proposed, and to the need for spending reductions. We also generally agree with the provisions of the plan. There may be specific matters, however, on which some of us have different views. Contents 1 Introduction and summary 5 On the need for more revenue 6 Why the additional revenue must come from high-income households 9 A progressive tax reform 11 Tax rates 12 Cleaning up the tax code 15 Simplifying filing 16 Other taxes 17 The spending side of the equation 20 Bottom line 22 About the authors 24 Acknowledgements 25 Endnotes Introduction and summary There are very few things everyone in Washington can agree on these days. But the one notion that will get heads nodding across the political spectrum is that today’s fiscal policies simply are not sustainable. If we keep doing what we’ve been doing, not only will the federal budget stay permanently deep in the red but critical public investments such as education and infrastructure will continue to go underfunded. -

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the William J

FOIA Number: 2006-0885-F. FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the William J. Clinton Presidential Library Staff. Collection/Record Group: Clinton Presidential Records Subgroup/Office of Origin: Health Care Task Force Series/Staff Member: Richard Veloz Subseries: OA/ID Number: 3882 FolderlD: Folder Title: [Health Care] [Folder 3]: Economic Team [1] Stack: Row: Section: Shelf: Position: S 56 4 8 3 r OVERVIEW OF BUSINESS OUTREACH STRATEGY October 15, 1993 BUILDING AND NURTURING CORE BUSINESS SUPPORT (staff: Marilyn Yager, Amy Zisook, & Marilyn DiGiacobbe) I. Identify and target key businesses who are beneficiaries of the Act. A. Big businesses who have: 1. Large retiree populations (attached). 2. Struggled to control the growth in their own health care costs and voiced their commitment to health reform (attached). 3. Strong international competition (need list from Commerce or Treasury). B. Mid to small size businesses who have been: 1. The target of redlining practices (list attached). 2. Currently providing health coverage at costs of 7% or greater (list developed from SBA, DNC, and White House outreach). II. Continue small group meetings with Washington representatives (or CFOs). The key briefers at these meetings are Ira Magaziner, Roger Altman, and Bob Rubin. They will be staffed by Glenn Hutchins, Christine Hennen, and Marilyn Yager. A. The purpose is to: 1. Shore up their understanding and comfort level with the details of the Act. 2. Provide ongoing opportunities to hear their concerns and suggestions. 3. Ask for their support and their assistance in recruiting support. Where outright support is not a possibility, efforts will be made to neutralize their public response. -

Global Crossing Approved to Sell Unit to Pivotal2 Thursday June 5, 12:39 Pm ET

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 ____________________________________ ) In the Matter of ) IB Docket No. 02-286 ) File Nos. ISP-PDR-20020822-0029; GLOBAL CROSSING, LTD. ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00406 (Debtor-in-Possession), ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00443 ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00444 Transferor, ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00445 ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00446 and ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00447 ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00449 ) ITC-T/C-20020822-00448 GC ACQUISITION LIMITED, ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00068 ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00070 Transferee ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00071 ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00072 Application for Consent to Transfer ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00077 Control and Petition for Declaratory ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00073 Ruling ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00074 ) SLC-T/C-20020822-00075 ) 0001001014 ____________________________________) COMMAXXESS’ FOURTH SUPPLEMENTAL RESPONSE TO ST TELEMEDIA’S THIRD APPLICATION FOR CONSENT TO TRANSFER CONTROL AND PETITION FOR DECLARATORY RULING On June 5, 2003 the United States Bankruptcy Court, SDNY approved the sale of Pacific Crossing Ltd for $63 million. The Global Crossing cable system and four landings in Japan and the United States were built at a cost of $1.35 billion. The disclosed buyer is Pivotal Private Equity1 and is a matter that demands the full scrutiny and attention of this Commission. These parties are attempting to do an end around on what CFIUS ruled on regarding Hutchison and dupe this Commission into approving change of control in a bifurcated manner that has the same end objective. Global Crossing approved to sell unit to Pivotal2 Thursday June 5, 12:39 pm ET 1 http://www.pivotalgroup.com/equitysenior.html 2 http://biz.yahoo.com/rc/030605/telecoms_globalcrossing_pivotal_1.html PHILADELPHIA, June 5 (Reuters) - Global Crossing Ltd. -

Dear Chairman

Dear Chairman Boardroom Battles and the Rise of Shareholder Activism JEFF GRAMM Chairman_xxiv_296_Final.indd 3 11/30/15 4:19 PM Contents Introduction . ix ". Benjamin Graham versus Northern Pipeline: The Birth of Modern Shareholder Activism . " #. Robert Young versus New York Central: The Proxyteers Storm the Vanderbilt Line . #$ %. Warren Bu&ett and American Express: The Great Salad Oil Swindle . '( '. Carl Icahn versus Phillips Petroleum: The Rise and Fall of the Corporate Raiders . )* (. Ross Perot versus General Motors: The Unmaking of the Modern Corporation . *( ). Karla Scherer versus R. P. Scherer: A Kingdom in a Capsule . "## +. Daniel Loeb and Hedge Fund Activism: The Shame Game . "'+ ,. BKF Capital: The Corrosion of Conformity . "+$ Conclusion . "*# Appendix: Original. Letters . #$% Acknowledgments . #(" Notes . #(( Index . #++ Chairman_xxiv_296_Final.indd 7 11/30/15 4:19 PM % Warren Buffett and American Express: The Great Salad Oil Swindle “Let me assure you that the great majority of stockholders (although per- haps not the most vocal ones) think you have done an outstanding job of keeping the ship on an even keel and moving full steam ahead while being buffetted by a typhoon which largely falls in the ‘Act of God’ category.” — !"##$% &'(($)), *+,- -../0 1233/44 5-6/7 809/7480: sound easy. Part of his investment philosophy comes directly from Benja- Wmin Graham: He views shares of stock as fractional owner- ships of a business, and he buys them with a margin of safety. But unlike Graham, when Bu&ett ;nds a security trading at a large discount to its intrinsic value, he eschews diversi;cation and buys a large position. To Warren Bu&ett, with his superhuman gift for rational thinking, this value investing strategy is easy.