The Universal Significance of Jefferson's Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Presidents of Mount Rushmore

The PReSIDeNTS of MoUNT RUShMoRe A One Act Play By Gloria L. Emmerich CAST: MALE: FEMALE: CODY (student or young adult) TAYLOR (student or young adult) BRYAN (student or young adult) JESSIE (student or young adult) GEORGE WASHINGTON MARTHA JEFFERSON (Thomas’ wife) THOMAS JEFFERSON EDITH ROOSEVELT (Teddy’s wife) ABRAHAM LINCOLN THEODORE “TEDDY” ROOSEVELT PLACE: Mount Rushmore National Memorial Park in Keystone, SD TIME: Modern day Copyright © 2015 by Gloria L. Emmerich Published by Emmerich Publications, Inc., Edenton, NC. No portion of this dramatic work may be reproduced by any means without specific permission in writing from the publisher. ACT I Sc 1: High school students BRYAN, CODY, TAYLOR, and JESSIE have been studying the four presidents of Mount Rushmore in their history class. They decided to take a trip to Keystone, SD to visit the national memorial and see up close the faces of the four most influential presidents in American history. Trying their best to follow the map’s directions, they end up lost…somewhere near the face of Mount Rushmore. All four of them are losing their patience. BRYAN: We passed this same rock a half hour ago! TAYLOR: (Groans.) Remind me again whose idea it was to come here…? CODY: Be quiet, Taylor! You know very well that we ALL agreed to come here this summer. We wanted to learn more about the presidents of Mt. Rushmore. BRYAN: Couldn’t we just Google it…? JESSIE: Knock it off, Bryan. Cody’s right. We all wanted to come here. Reading about a place like this isn’t the same as actually going there. -

Independence Day at Monticello (.Pdf

INDEPENDENCE DAY AT MONTICELLO JULY 2017 “The only birthday I ever commemorate is that of our Independence, the Fourth of July.” - Margaret Bayard Smith quoting Thomas Jefferson, 1801 There is no more inspirational place to celebrate the Fourth of July than Monticello, the home of the author of the Declaration of Independence. Since 1963, more than 3,000 people from every corner of the globe have taken the oath of citizenship at the annual Monticello Independence Day Celebration and Naturalization Ceremony. Jefferson himself hoped that Americans would celebrate the Fourth of July, what he called “the great birthday of our Republic,” to “refresh our collections of [our] rights, and undiminished devotion to them.” The iconic West Lawn of Monticello provides a glorious setting for a ceremony steeped in patriotic elements. “Monticello is a beautiful spot for this, full as it is of the spirit that animated this country’s foundation: boldness, vision, improvisation, practicality, inventiveness and imagination, the kind of cheekiness that only comes from free-thinking and faith in an individual’s ability to change the face of the world — it’s easy to imagine Jefferson saying to himself, “So what if I’ve never designed a building before? If I want to, I will...” - Excerpt from Sam Waterston’s remarks at Monticello, 2007 It is said that we are a nation of immigrants. The list of those who have delivered the July 4th address at Monticello is a thoroughly American story. In 1995 there was Roberto Goizueta, the man who fled Cuba with nothing but an education and a job, and who rose to lead one of the best known corporations: The Coca-Cola Company. -

Mount Rushmore: a Tomb for Dead Ideas of American Greatness in June of 1927, Albert Burnley Bibb, Professor of Architecture at George Washington

Caleb Rollins 1 Mount Rushmore: A Tomb for Dead Ideas of American Greatness In June of 1927, Albert Burnley Bibb, professor of architecture at George Washington University remarked in a plan for The National Church and Shrine of America, “[T]hrough all the long story of man’s mediaeval endeavor, the people have labored at times in bonds of more or less common faith and purpose building great temples of worship to the Lords of their Destiny, great tombs for their noble dead.”1 Bibb and his colleague Charles Mason Remey were advocating for the construction of a national place for American civil religion in Washington, D.C. that would include a place for worship and tombs to bury the great dead of the nation. Perhaps these two gentleman knew that over 1,500 miles away in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a group of intrepid Americans had just begun to make progress on their own construction of a shrine of America, Mount Rushmore. These Americans had gathered together behind a common purpose of building a symbol to the greatness of America, and were essentially participating in the human tradition of construction that Bibb presented. However, it is doubtful that the planners of this memorial knew that their sculpture would become not just a shrine for America, but also like the proposed National Church and Shrine a tomb – a tomb for the specific definitions of American greatness espoused by the crafters of Mt. Rushmore. In 1924 a small group of men initiated the development of the memorial of Mount Rushmore and would not finish this project until October of 1941. -

Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond

Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond Restoring Pedestrian and Bicycle Connections Maura Harris Caroline Herre Peter Krebs Joel Lehman Julie Murphy Department of Urban and Environmental Planning University of Virginia School of Architecture May 2017 Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond Restoring Pedestrian and Bicycle Connections Maura Harris, Caroline Herre, Peter Krebs, Joel Lehman, and Julie Murphy Department of Urban and Environmental Planning University of Virginia School of Architecture May 2017 Sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission Info & Inquiries: http://cvilletomonticello.weebly.com/ Acknowledgments This report was written to satisfy the course requirements of PLAN- 6010 Planning Process and Practice, under the direction of professors Ellen Bassett and Kathy Galvin, as well as Will Cockrell at the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission, our sponsor. We received guidance from an extraordinary advisory committee: Niya Bates, Monticello, Public Historian Sara Bon-Harper, James Monroe’s Highland Will Cockrell, Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission Chris Gensic, City of Charlottesville, Parks Carly Griffith, Center for Cultural Landscapes Neal Halvorson-Taylor, Morven Farms, Sustainability Dan Mahon, Albemarle County, Parks Kevin McDermott, Albemarle County Transportation Planner Fred Missel, UVa Foundation Andrew Mondschein, UVa School of Architecture Peter Ohlms, Virginia Transportation Research Council Amanda Poncy, Charlottesville Bicycle/Pedestrian Coordinator Julie Roller, Monticello Trail Manager Liz Russell, Monticello, Planning We received substantial research support from the UVa School of Architecture and a host of stakeholders and community groups. Thank you—this would not have happened without you. Cover Photos: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Peter Krebs, Julie Murphy. Executive Summary Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello is an important source of Charlottesville’s Stakeholders requested five areas of investigation: history, cultural identity and economic vitality. -

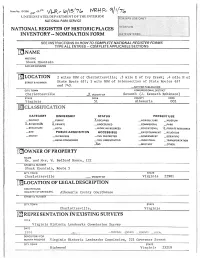

Nomination Form

141 Form No. 10-300 ,o- ' 'J-R - ft>( 15/r (i;, ~~- V ' I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPSUSE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF IIlSTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS- - - - - [EINAME HISTORIC Shack Mountain AND/OR COMMON raLOCATION 2 miles NNW of Charlottesville; .3 mile E of Ivy Creek; .4 mile N of STREET & NUMBER State Route 657; 1 mile NNW of intersection of State Routes 657 and 743. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Charlottesville _2( VICINITY OF Seventh (J. Kenneth Robinson) STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 Albemarle 003 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC XoccuP1Eo _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM X...BUILDING!S) X..PRIVATE _UNOCCUPIED _COMMERCIAL _PARK _STRUCTURE _BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT -RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS -YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED - YES: UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL -TRANSPORTATION -~O _MILITARY _OTHER: [~OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. and Mrs. W. Bedford Moore, I II STREET & NUMBER Shack Mounta_in, Route 5 CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville _ VICINITY OF Virginia 22901 [ELOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Albemarle County Courthouse - ---•---------------------------------------~ STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville. Virginia l~ REPRESENTATION I1'fEXISTING SURVEYS TITLE -

The Thomas Jefferson Memorial, Washington

JL, JLornclt ),//,.,on Wn*ooio/ memorial ACTION PUBLICATIONS Alexandria, Va. JL" llo*oo )"ff",.", TLln^o,io/ This great National Memorial to the aurhor of the Declaration of Indepen- dence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, First Secretary of State and Third President of the United States, possesses mlny of the qualities ascribed to the brilliant revolutionary leader in whose memory it has been dedicated by a grateful Nation It is magnificent-as Jefferson's chrracter was magnificent. Simple as his Democracy. Aesthetic as l.ris thoughts. Courageous as his chempion- ship of the righrs of man. The memorial structure is in itself a tribute to Jefferson's artistic tastes and preference and a mark of respect for his architectural and scientific achievements. A farmer by choice, a lawyer by profession, and an architect by avocation, JelTer- son \r,as awed by the remarkable beauty of design and noble proportions of the Pantheon in Rome and foilou,ed irs scheme in the major architectururl accom- plishments of his oq,n life Its inlluence is evident in his ovu'n home at Monticello and in the Rotunda of the University of Virginia at Cl.rarkrttesville, which he designed. The monumental portico complimenrs Jellerson's design for the Yir- ginia State Capitol at Richmond. h But it is not alone the architectural splendor or the beiruty of its settir,g ',irhich makes this memcrial one of the mosr revered American patriotic shrines. In it the American people find the spirit of the living Jefferson and the fervor which inspired their colonial forbears to break, by force of erms, the ties which bound them to tyrannical overlords; to achieve not only nltional independence. -

Monticello High School Profile 2018-2019

1400 Independence Way, Charlottesville, VA 22902 MONTICELLO School Counseling Office Phone: (434) 244-3110 FAX: (434) 244-3109 Main Office Phone: (434) 244-3100 HIGH SCHOOL FAX: (434) 244-3104 PRINCIPAL: 2018-2019 School Profile Mr. Ricky Eric Vrhovac Our School And Community ASSOCIATE PRINCIPAL: Mr. Reed Gillespie Monticello High School (MoHS) is one of three comprehensive public high schools in ASSISTANT PRINCIPALS: Albemarle County. Named for Thomas Jefferson’s historical mountainside estate, Mr. Henry Atkins Mrs. Melissa Hankins “Monticello” means “little mountain” in Old Italian. Monticello High School is located two hours south of Washington, D.C. and one hour west of Richmond, VA. Monticello High has an SCHOOL COUNSELING DIRECTOR: Mr. Irvin Johnson (AVID) enrollment of approximately 1150 students, servicing grades 9-12. Monticello operates on a modified block schedule. Classes are offered either yearlong, meeting every other day or for SCHOOL COUNSELORS: one semester, meeting every day. Ms. Najwa Tatby (A-C) Mr. Paul Jones (D-Hod) Mrs. Laura Gaskins (Hoe-Mel) Curriculum Mr. Adam Southall (Mem-Sea) Monticello High offers a comprehensive curriculum that stresses academics, but includes am- Ms. Nikki Eubanks( Seb-Z) Ms. Shamika Terrell (Career Specialist) ple opportunity for students to study the fine arts as well as vocational courses at the local CATEC School. Our programs with University of Virginia and Piedmont Virginia Community SCHOOL COUNSELING Associate: College allow students to enroll in college courses for dual credit. In addition, extracurricular Ms. Connie Jenkins Database Administrator/Registrar: opportunities through groups like the Key Club, Robotics Team, and Habitat for Humanity Mr. Corey Hunt Club, as well as all of the honors societies, give students a chance to get involved in the school CEEB CODE: 470-439 and the community. -

2019-2020 Missouri Roster

The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 Secretary of State John R. Ashcroft State Capitol Room 208 Jefferson City, MO 65101 www.sos.mo.gov John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Cover image: A sunrise appears on the horizon over the Missouri River in Jefferson City. Photo courtesy of Tyler Beck Photography www.tylerbeck.photography The Missouri Roster 2019–2020 A directory of state, district, county and federal officials John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State Office of the Secretary of State State of Missouri Jefferson City 65101 STATE CAPITOL John R. Ashcroft ROOM 208 SECRETARY OF STATE (573) 751-2379 Dear Fellow Missourians, As your secretary of state, it is my honor to provide this year’s Mis- souri Roster as a way for you to access Missouri’s elected officials at the county, state and federal levels. This publication provides contact information for officials through- out the state and includes information about personnel within exec- utive branch departments, the General Assembly and the judiciary. Additionally, you will find the most recent municipal classifications and results of the 2018 general election. The strength of our great state depends on open communication and honest, civil debate; we have been given an incredible oppor- tunity to model this for the next generation. I encourage you to par- ticipate in your government, contact your elected representatives and make your voice heard. Sincerely, John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State www.sos.mo.gov The content of the Missouri Roster is public information, and may be used accordingly; however, the arrangement, graphics and maps are copyrighted material. -

Fiske Kimball and Preservation at the Powel House

Front Parlor Much like Kimball, the methods that he employed at the Powel House could bought the house in 1931, Kimball eventually supported her efforts by be problematic. However, it is important to remember that because of his presenting Landmarks with the original woodwork taken from this room (as it As you enter the front parlor, take a moment to examine the furniture in the training and experience, Kimball believed he was doing what was necessary was not being used by the Museum) and loaning her some of the furniture. room and the architecture above the fireplace. All of these pieces have been and right to save the legacy of the Powel House. His method involved Due to the return of the room’s moldings and trim, it is one of the only rooms preserved and maintained so that they could be seen and studied today. While purchasing the key architectural pieces of the house, such as the woodwork, in the house that is original and not a reconstruction. In this room then, it is this room is the simplest architecturally because it was the only room the and reconstructing them at the Art Museum to be displayed as period rooms important to think about how history is remembered and preserved. It is not general public had access to when conducting business with Samuel and later along with contemporary furniture and paintings. Today, such invasive enough to just save the physical pieces but preservation must also engage with Elizabeth Powel, it has been preserved for the sake of the stories it can tell. -

October 1916

[Sg^gg^^ / tamiiHffiy1^ ^\\ r] ARCHITEOJVRAL D aiiiafigoj b r -- * i-ir+X. Vol. XLVI. No. 4 OCTOBER, 1919 Serial N o 25 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: J. A. OAKLEY COVEK Water Color, by Jack Manley Rose PAGE THE AMERICAN COUNTRY HOUSE . .;. .-. 291 By Prof. Fiske Kimball. I. Practical Conditions: Natural, Economic, Social . ,. *.,, . 299 II. Artistic Conditions : Traditions and Ten^ dencies of Style . \ . .- 329 III. The Solutions : Disposition and Treatment of House and Surroundings . 350 J . .Vi Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Stn<7?e copies 33 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL:TURAL RECORD COMPANY VEST FORTIETH STKEET, NEW YORK F. T. MILLER, Pres. XL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. E. S. DODGE, Vice-Pi* ''< w : : f'lfvjf !?-; ^Tt;">7<"!{^if ^J^Y^^''*'C I''-" ^^ '^'^''^>'**-*'^j"^4!V; TIG. 1. DETAIL RESIDENCE OF H. BELLAS HESS, ESQ., HUNT1NGTON, L. I HOWELLS & STOKES, ARCHITECTS. AKCHITECTVKAL KECORD VOLVME XLVI NVMBER IV OCTOBER, 1919 <Amerioan Country <House By Fiskc KJmball the "country house" in America scribed "lots" of the city, where one may we understand no such single well- enjoy the informality of nature out-of- BYestablished form as the traditional doors. country house of England, fixed by cen- Much as has been written on the sub- turies of almost unalterable custom, with ject, we are still far from having any a life of its own which has been described such fundamental analysis of the Amer- as "the perfection of human society." ican country house of today as that Even in England today the great house which Hermann Muthesius in his classic yields in importance to the new and book "The English House" has given for smaller types which the rise of the middle England. -

Barboursville

Today, Barboursville’s “downtown” (right) features the Nichols Gallery Annex, the DOWN HOME SERIES Nichols Studio, Sun’s Traces Gallery, the community post office and Masonic Lodge. Again in the year 2005, we’re making Centreville 66 our way around the region, each McGaheysvilleMcGaheysville Barboursville issue visiting a small town and meeting Barboursville AT A GLANCE... some of the folks who make up 95 PPoort Royal POPULATION: Barboursville 81 the heart of electric co-op country. Charlottesville Post Office serves 4,025. 64 64 On this year’s last Richmond BelleBelle Haven Paint Bank LAND AREA: Barboursville has stop, we’ll be ... Roanoke 460 no formal boundaries. 81 HHuurt 85 Surry BigBig Stone Gap 77 95 INCORPORATED: : Part of Boydton Orange County, Barboursville is unincorporated. ELEVATION: 510 feet. DOWN HOME IN FUN FACT: Barboursville is the birthplace of Zachary Taylor, the BARBOURSVILLE 12th president of the U.S. by Jeff Poole, Contributing Writer or people traveling through central Orange County. Gianni Zonin planted and Thomas Jefferson (Monticello). Bar- Virginia, Barboursville is pretty much grapes and during the next three decades, bour’s home was built in a neoclassical F on the way to wherever they’re going. Barboursville cultivated a rich blend of Jefferson design that strikingly resembled Intersected east and west by Route 33 and arts and culture and reaped the benefits of the more famous home to the south in north and south by Route 20, Barboursville rural tourism. nearby Albemarle County. has long been recognized as a stop on the Barboursville is named for former According to local historian and author way — whichever that way was. -

A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders at Poplar Forest, University of Virginia, and Barboursville

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1997 A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders at Poplar Forest, University of Virginia, and Barboursville Kristin Meredith Fetzer University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Fetzer, Kristin Meredith, "A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders at Poplar Forest, University of Virginia, and Barboursville" (1997). Theses (Historic Preservation). 391. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/391 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Fetzer, Kristin Meredith (1997). A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders at Poplar Forest, University of Virginia, and Barboursville. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/391 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders at Poplar Forest, University of Virginia, and Barboursville Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Fetzer, Kristin Meredith (1997). A Comparative Study of Thomas Jefferson's Renders