The Publicity of Monticello: a Private Home As Emblem and Means Benjamin Block [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Be a Virginian

8/24/2018 To Be a Virginian . 1 18 19 1 8/24/2018 Lee County is closer to Mountain Region – the capitals of 7 other 20 19 counties, 4 independent states than to Richmond: Columbus, cities Population: 557,000 Frankfort, Charleston, 7% of VA population Nashville, Raleigh, Columbia, and Atlanta. 21 Valley Region – 14 counties and 9 independent cities Population: 778,200 9% of VA population 22 Something Special about Highland County Location of “Dividing Waters” farm The origins of the Potomac and James Rivers are less than ¼ mile apart Virginia was “almost” an island. 2 8/24/2018 23 Northern Region – 10 counties and 6 independent cities Population: 2,803,000 34% of VA population 24 Coastal Region – (also known as Tidewater) – 19 counties and 9 independent cities Population: 1,627,900 42% of VA population 25 Maryland Northern Neck Middle Peninsula Chesapeake Peninsula Bay James River Southside 3 8/24/2018 26 And this area is called “The Eastern Shore” – and don’t you forget it! 27 Central Region – 35 counties and 11 independent cities Population: 1,600,000 20% of VA population 28 4 8/24/2018 Things to Understand about 29 Virginia Politics Virginia is a Commonwealth (as are Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky) Significant to the Virginians who declared independence in 1776 – probably looking at the “commonwealth” (no king) during the English Civil War of the 1640s – 1650s. No current significance Things to Understand about 30 Virginia Politics Voters do not register by political party Elections are held in odd-numbered years House of -

The Presidents of Mount Rushmore

The PReSIDeNTS of MoUNT RUShMoRe A One Act Play By Gloria L. Emmerich CAST: MALE: FEMALE: CODY (student or young adult) TAYLOR (student or young adult) BRYAN (student or young adult) JESSIE (student or young adult) GEORGE WASHINGTON MARTHA JEFFERSON (Thomas’ wife) THOMAS JEFFERSON EDITH ROOSEVELT (Teddy’s wife) ABRAHAM LINCOLN THEODORE “TEDDY” ROOSEVELT PLACE: Mount Rushmore National Memorial Park in Keystone, SD TIME: Modern day Copyright © 2015 by Gloria L. Emmerich Published by Emmerich Publications, Inc., Edenton, NC. No portion of this dramatic work may be reproduced by any means without specific permission in writing from the publisher. ACT I Sc 1: High school students BRYAN, CODY, TAYLOR, and JESSIE have been studying the four presidents of Mount Rushmore in their history class. They decided to take a trip to Keystone, SD to visit the national memorial and see up close the faces of the four most influential presidents in American history. Trying their best to follow the map’s directions, they end up lost…somewhere near the face of Mount Rushmore. All four of them are losing their patience. BRYAN: We passed this same rock a half hour ago! TAYLOR: (Groans.) Remind me again whose idea it was to come here…? CODY: Be quiet, Taylor! You know very well that we ALL agreed to come here this summer. We wanted to learn more about the presidents of Mt. Rushmore. BRYAN: Couldn’t we just Google it…? JESSIE: Knock it off, Bryan. Cody’s right. We all wanted to come here. Reading about a place like this isn’t the same as actually going there. -

2020 Virginia Capitol Connections

Virginia Capitol Connections 2020 ai157531556721_2020 Lobbyist Directory Ad 12022019 V3.pdf 1 12/2/2019 2:39:32 PM The HamptonLiveUniver Yoursity Life.Proto n Therapy Institute Let UsEasing FightHuman YourMisery Cancer.and Saving Lives You’ve heard the phrases before: as comfortable as possible; • Treatment delivery takes about two minutes or less, with as normal as possible; as effective as possible. At Hampton each appointment being 20 to 30 minutes per day for one to University Proton The“OFrapy In ALLstitute THE(HUPTI), FORMSwe don’t wa OFnt INEQUALITY,nine weeks. you to live a good life considering you have cancer; we want you INJUSTICE IN HEALTH IS THEThe me MOSTn and wome n whose lives were saved by this lifesaving to live a good life, period, and be free of what others define as technology are as passionate about the treatment as those who possible. SHOCKING AND THE MOSTwo INHUMANrk at the facility ea ch and every day. Cancer is killing people at an alBECAUSEarming rate all acr osITs ouOFTENr country. RESULTSDr. William R. Harvey, a true humanitarian, led the efforts of It is now the leading cause of death in 22 states, behind heart HUPTI becoming the world’s largest, free-standing proton disease. Those states are Alaska, ArizoINna ,PHYSICALCalifornia, Colorado DEATH.”, therapy institute which has been treating patients since August Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, 2010. Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, NewREVERENDHampshir DR.e, Ne MARTINw Me LUTHERxico, KING, JR. North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West “A s a patient treatment facility as well as a research and education Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

Independence Day at Monticello (.Pdf

INDEPENDENCE DAY AT MONTICELLO JULY 2017 “The only birthday I ever commemorate is that of our Independence, the Fourth of July.” - Margaret Bayard Smith quoting Thomas Jefferson, 1801 There is no more inspirational place to celebrate the Fourth of July than Monticello, the home of the author of the Declaration of Independence. Since 1963, more than 3,000 people from every corner of the globe have taken the oath of citizenship at the annual Monticello Independence Day Celebration and Naturalization Ceremony. Jefferson himself hoped that Americans would celebrate the Fourth of July, what he called “the great birthday of our Republic,” to “refresh our collections of [our] rights, and undiminished devotion to them.” The iconic West Lawn of Monticello provides a glorious setting for a ceremony steeped in patriotic elements. “Monticello is a beautiful spot for this, full as it is of the spirit that animated this country’s foundation: boldness, vision, improvisation, practicality, inventiveness and imagination, the kind of cheekiness that only comes from free-thinking and faith in an individual’s ability to change the face of the world — it’s easy to imagine Jefferson saying to himself, “So what if I’ve never designed a building before? If I want to, I will...” - Excerpt from Sam Waterston’s remarks at Monticello, 2007 It is said that we are a nation of immigrants. The list of those who have delivered the July 4th address at Monticello is a thoroughly American story. In 1995 there was Roberto Goizueta, the man who fled Cuba with nothing but an education and a job, and who rose to lead one of the best known corporations: The Coca-Cola Company. -

Mount Rushmore: a Tomb for Dead Ideas of American Greatness in June of 1927, Albert Burnley Bibb, Professor of Architecture at George Washington

Caleb Rollins 1 Mount Rushmore: A Tomb for Dead Ideas of American Greatness In June of 1927, Albert Burnley Bibb, professor of architecture at George Washington University remarked in a plan for The National Church and Shrine of America, “[T]hrough all the long story of man’s mediaeval endeavor, the people have labored at times in bonds of more or less common faith and purpose building great temples of worship to the Lords of their Destiny, great tombs for their noble dead.”1 Bibb and his colleague Charles Mason Remey were advocating for the construction of a national place for American civil religion in Washington, D.C. that would include a place for worship and tombs to bury the great dead of the nation. Perhaps these two gentleman knew that over 1,500 miles away in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a group of intrepid Americans had just begun to make progress on their own construction of a shrine of America, Mount Rushmore. These Americans had gathered together behind a common purpose of building a symbol to the greatness of America, and were essentially participating in the human tradition of construction that Bibb presented. However, it is doubtful that the planners of this memorial knew that their sculpture would become not just a shrine for America, but also like the proposed National Church and Shrine a tomb – a tomb for the specific definitions of American greatness espoused by the crafters of Mt. Rushmore. In 1924 a small group of men initiated the development of the memorial of Mount Rushmore and would not finish this project until October of 1941. -

Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond

Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond Restoring Pedestrian and Bicycle Connections Maura Harris Caroline Herre Peter Krebs Joel Lehman Julie Murphy Department of Urban and Environmental Planning University of Virginia School of Architecture May 2017 Charlottesville to Monticello & Beyond Restoring Pedestrian and Bicycle Connections Maura Harris, Caroline Herre, Peter Krebs, Joel Lehman, and Julie Murphy Department of Urban and Environmental Planning University of Virginia School of Architecture May 2017 Sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission Info & Inquiries: http://cvilletomonticello.weebly.com/ Acknowledgments This report was written to satisfy the course requirements of PLAN- 6010 Planning Process and Practice, under the direction of professors Ellen Bassett and Kathy Galvin, as well as Will Cockrell at the Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission, our sponsor. We received guidance from an extraordinary advisory committee: Niya Bates, Monticello, Public Historian Sara Bon-Harper, James Monroe’s Highland Will Cockrell, Thomas Jefferson Planning District Commission Chris Gensic, City of Charlottesville, Parks Carly Griffith, Center for Cultural Landscapes Neal Halvorson-Taylor, Morven Farms, Sustainability Dan Mahon, Albemarle County, Parks Kevin McDermott, Albemarle County Transportation Planner Fred Missel, UVa Foundation Andrew Mondschein, UVa School of Architecture Peter Ohlms, Virginia Transportation Research Council Amanda Poncy, Charlottesville Bicycle/Pedestrian Coordinator Julie Roller, Monticello Trail Manager Liz Russell, Monticello, Planning We received substantial research support from the UVa School of Architecture and a host of stakeholders and community groups. Thank you—this would not have happened without you. Cover Photos: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Peter Krebs, Julie Murphy. Executive Summary Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello is an important source of Charlottesville’s Stakeholders requested five areas of investigation: history, cultural identity and economic vitality. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/scholarly-editions-and-translations-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Institution: Princeton University Project Director: Barbara Bowen Oberg Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Statement of Significance and Impact of Project This project is preparing the authoritative edition of the correspondence and papers of Thomas Jefferson. Publication of the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1950 kindled renewed interest in the nation’s documentary heritage and set new standards for the organization and presentation of historical documents. Its impact has been felt across the humanities, reaching not just scholars of American history, but undergraduate students, high school teachers, journalists, lawyers, and an interested, inquisitive American public. -

Palladio's Influence in America

Palladio’s Influence In America Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian, Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2008 marks the 500th anniversary of Palladio’s birth. We might ask why Americans should consider this to be a cause for celebration. Why should we be concerned about an Italian architect who lived so long ago and far away? As we shall see, however, this architect, whom the average American has never heard of, has had a profound impact on the architectural image of our country, even the city of Baltimore. But before we investigate his influence we should briefly explain what Palladio’s career involved. Palladio, of course, designed many outstanding buildings, but until the twentieth century few Americans ever saw any of Palladio’s works firsthand. From our standpoint, Palladio’s most important achievement was writing about architecture. His seminal publication, I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura or The Four Books on Architecture, was perhaps the most influential treatise on architecture ever written. Much of the material in that work was the result of Palladio’s extensive study of the ruins of ancient Roman buildings. This effort was part of the Italian Renaissance movement: the rediscovery of the civilization of ancient Rome—its arts, literature, science, and architecture. Palladio was by no means the only architect of his time to undertake such a study and produce a publication about it. Nevertheless, Palladio’s drawings and text were far more engaging, comprehendible, informative, and useful than similar efforts by contemporaries. As with most Renaissance-period architectural treatises, Palladio illustrated and described how to delineate and construct the five orders—the five principal types of ancient columns and their entablatures. -

Gift Report 2013

SPRING 2014 www.monticello.org VOLUME 25, NUMBER 1 GIFT REPORT 2013 THOMAS JEFFERSON'S HOMAS JEFFERSON is best remembered as Lthe author egacyegacy of the Declaration of Independence. The ideaL that “all men are created equal” with a right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” established the foundations of self- Tgovernment and personal liberty in America. Jefferson’s eloquent words of 1776 continue to inspire people of all ages around the world today. Today, Jefferson’s home remains a touchstone for all who seek to explore the enduring meaning of what it means to be an American and a citizen of the world. Since 1923, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has been dedicated to preserving Monticello, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and sharing Jefferson’s home and ideas with the world. Park Historical National Independence Courtesy Giving to Monticello EACH YEAR: Ë Close to 440,000 people visit Jefferson’s mountaintop home—the only home in s a private, nonprofit America recognized by the United Nations as a World Heritage Site. organization, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation receives Ë More than 2.7 million visit our website, monticello.org. noA government funding for Monticello’s Ë Monticello’s K-12 guided student field trips serve more than . 60,000 students general operations, and visitor ticket Ë More than 153,000 walkers, runners and bikers enjoy the Saunders-Monticello Trail. sales cover less than 50 percent of our operating costs. The Foundation relies Ë The Center for Historic Plants sells seeds and plants to over 18,000 people, on the private support of donors like preserving horticultural heritage. -

Albemarle County in Virginia

^^m ITD ^ ^/-^7^ Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arGhive.org/details/albemarlecountyiOOwood ALBEMARLE COUNTY IN VIIIGIMIA Giving some account of wHat it -was by nature, of \srHat it was made by man, and of some of tbe men wHo made it. By Rev. Edgar Woods " It is a solemn and to\acKing reflection, perpetually recurring. oy tHe -weaKness and insignificance of man, tHat -wKile His generations pass a-way into oblivion, -with all tKeir toils and ambitions, nature Holds on Her unvarying course, and pours out Her streams and rene-ws Her forests -witH undecaying activity, regardless of tHe fate of Her proud and perisHable Sovereign.**—^e/frey. E.NEW YORK .Lie LIBRARY rs526390 Copyright 1901 by Edgar Woods. • -• THE MicHiE Company, Printers, Charlottesville, Va. 1901. PREFACE. An examination of the records of the county for some in- formation, awakened curiosity in regard to its early settle- ment, and gradually led to a more extensive search. The fruits of this labor, it was thought, might be worthy of notice, and productive of pleasure, on a wider scale. There is a strong desire in most men to know who were their forefathers, whence they came, where they lived, and how they were occupied during their earthly sojourn. This desire is natural, apart from the requirements of business, or the promptings of vanity. The same inquisitiveness is felt in regard to places. Who first entered the farms that checker the surrounding landscape, cut down the forests that once covered it, and built the habitations scattered over its bosom? With the young, who are absorbed in the engagements of the present and the hopes of the future, this feeling may not act with much energy ; but as they advance in life, their thoughts turn back with growing persistency to the past, and they begin to start questions which perhaps there is no means of answering. -

Nomination Form

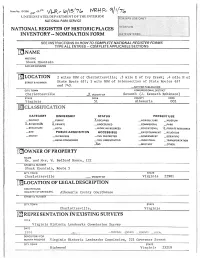

141 Form No. 10-300 ,o- ' 'J-R - ft>( 15/r (i;, ~~- V ' I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPSUSE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF IIlSTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS- - - - - [EINAME HISTORIC Shack Mountain AND/OR COMMON raLOCATION 2 miles NNW of Charlottesville; .3 mile E of Ivy Creek; .4 mile N of STREET & NUMBER State Route 657; 1 mile NNW of intersection of State Routes 657 and 743. _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Charlottesville _2( VICINITY OF Seventh (J. Kenneth Robinson) STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Virginia 51 Albemarle 003 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC XoccuP1Eo _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM X...BUILDING!S) X..PRIVATE _UNOCCUPIED _COMMERCIAL _PARK _STRUCTURE _BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS _EDUCATIONAL 2LPRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE -ENTERTAINMENT -RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS -YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED - YES: UNRESTRICTED _INDUSTRIAL -TRANSPORTATION -~O _MILITARY _OTHER: [~OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. and Mrs. W. Bedford Moore, I II STREET & NUMBER Shack Mounta_in, Route 5 CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville _ VICINITY OF Virginia 22901 [ELOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Albemarle County Courthouse - ---•---------------------------------------~ STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Charlottesville. Virginia l~ REPRESENTATION I1'fEXISTING SURVEYS TITLE -

Fond Du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826

Fond du Lac Treaty Portraits: 1826 RICHARD E. NELSON Duluth, Minnesota The story of the Fond du Lac Treaty portraits began on the St. Louis River at a site near the present city of Duluth with these words: Whereas a treaty between the United States of America and the Chippeway tribe of Indians, was made and concluded on the fifth day of August, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-six, at the Fond du Lac of Lake Superior, in the territory of Michigan, by Commissioners on the part of the United States, and certain Chiefs and Warriors of the said tribe . (McKenney 1959:479) The location was memorialized by a monument erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Duluth, Minnesota, on November 21, 1922, which reads: Fond du Lac, Minnesota. Site of an Ojibway village from the earliest known pe riod. Daniel Greysolon Sieur de Lhut was here in 1679. Astor's American Fur Company established a trading post on this spot about 1817. First Ojibway treaty in Minnesota made here in 1826. The report of the treaty is recorded in Sketches of a Tour to the Lakes, of the Character and Customs of the Chippeway Indians, and of Incidents Connected with the Treaty of Fond du Lac written by Thomas K. McKenney in the form of letters to Secretary of War James Barbour in Washington and first published in 1827. McKenney was the head of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. In May of 1826 he and Lewis Cass, the governor of the Michigan Territory, were appointed by President John Quincy Adams to conclude a major treaty at Fond du Lac.