Current Knowledge on Snake Dry Bites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESEARCH ARTICLE Anti-Glioma Effect of Pseudosynanceia

DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.7.2295 Effect of Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma Venom on Glioblastoma Cells RESEARCH ARTICLE Editorial Process: Submission:02/14/2021 Acceptance:07/15/2021 Anti-Glioma Effect of Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma Venom on Isolated Mitochondria from Glioblastoma Cells Maral Ramezani, Fatemeh Samiei, Jalal Pourahmad* Abstract Background: Glioblastoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the central nervous system that occurs in the spinal cord or brain. Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma is a venomous stonefish in the Persian Gulf, which our knowledge about is little. This study’s goal is to investigate the toxicity of stonefish crude venom on mitochondria isolated from U87 cells. Methods: In the first stage, we extracted venom stonefish and then isolated mitochondria have exposed to different concentrations of venom. Finally, mitochondrial toxicity parameters (Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity, Reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytochrome c release, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP), and mitochondrial swelling) have evaluated. Results: To determine mitochondrial parameters, we used 115, 230, and 460 µg/ml concentrations. The results of our study show that the venom of stonefish selectively increases upstream parameters of apoptosis such as mitochondrial swelling, cytochrome c release, MMP collapse and ROS. Conclusion: This study suggests that Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma crude venom has selectively caused toxicity by increasing active mitochondrial oxygen radicals. This venom could potentially be a candidate for the treatment of glioblastoma. Keywords: Mitochondria- glioblastoma- fish venoms- cell line- tumor- toxicity-Persian Gulf Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 22 (7), 2295-2302 Introduction freshwater or saltwater. Marine animals most commonly used for animals live in saltwater, i.e. in oceans, seas, Glioblastoma multiform is the most common group of etc. -

Rachel Carson for SILENT SPRING

Silent Spring THE EXPLOSIVE BESTSELLER THE WHOLE WORLD IS TALKING ABOUT RACHEL CARSON Author of THE SEA AROUND US SILENT SPRING, winner of 8 awards*, is the history making bestseller that stunned the world with its terrifying revelation about our contaminated planet. No science- fiction nightmare can equal the power of this authentic and chilling portrait of the un-seen destroyers which have already begun to change the shape of life as we know it. “Silent Spring is a devastating attack on human carelessness, greed and irresponsibility. It should be read by every American who does not want it to be the epitaph of a world not very far beyond us in time.” --- Saturday Review *Awards received by Rachel Carson for SI LENT SPRING: • The Schweitzer Medal (Animal Welfare Institute) • The Constance Lindsay Skinner Achievement Award for merit in the realm of books (Women’s National Book Association) • Award for Distinguished Service (New England Outdoor Writers Association) • Conservation Award for 1962 (Rod and Gun Editors of Metropolitan Manhattan) • Conservationist of the Year (National Wildlife Federation) • 1963 Achievement Award (Albert Einstein College of Medicine --- Women’s Division) • Annual Founders Award (Isaak Walton League) • Citation (International and U.S. Councils of Women) Silent Spring ( By Rachel Carson ) • “I recommend SILENT SPRING above all other books.” --- N. J. Berrill author of MAN’S EMERGING MIND • "Certain to be history-making in its influence upon thought and public policy all over the world." --Book-of-the-Month Club News • "Miss Carson is a scientist and is not given to tossing serious charges around carelessly. -

On Elevation-Related Shifts of Spring Activity in Male Vipers of the Genera

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2019 Band/Volume: 31_3_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Stümpel Nikolaus, Zinenko Oleksander, Mebert Konrad Artikel/Article: on elevation-related shifts of spring activity in male vipers of the genera Montivipera and Macrovipera in Turkey and Cyprus 125-132 StuempelZinenkoMebert_Spring_activity_Montivipera-Macrovipera:HERPETOZOA.qxd 12.02.2019 15:04 Seite 1 HERPEToZoA 31 (3/4): 125 - 132 125 Wien, 28. Februar 2019 on elevation-related shifts of spring activity in male vipers of the genera Montivipera and Macrovipera in Turkey and Cyprus (squamata: serpentes: Viperidae) Zur höhenabhängigen Frühjahrsaktivität männlicher Vipern der Gattungen Montivipera und Macrovipera in der Türkei und Zypern (squamata: serpentes: Viperidae) NikolAus sTüMPEl & o lEksANdR ZiNENko & k oNRAd MEbERT kuRZFAssuNG der zeitliche Ablauf von lebenszyklen wechselwarmer Wirbeltiere wird in hohem Maße vom Temperaturregime des lebensraumes bestimmt. in Gebirgen sinkt die umgebungstemperatur mit zunehmender Höhenlage. deshalb liegt es nahe, anzunehmen, daß die Höhenlage den Zeitpunkt des beginns der Frühjahres - aktivität von Vipern beeinflußt. um diesen Zusammenhang zu untersuchen, haben die Autoren im Zeitraum von 2004 bis 2015 in der Türkei und auf Zypern den beginn der Frühjahrshäutung bei männlichen Vipern der Gattun - gen Montivipera und Macrovipera zwischen Meereshöhe und 2300 m ü. M. untersucht. sexuell aktive Männchen durchlaufen nach der Winterruhe und vor der Paarung eine obligatorische Frühjahrshäutung. im Häutungsprozeß werden äußerlich klar differenzierbare stadien durchschritten, von denen die Eintrübung des Auges besonders auffällig und kurzzeitig ist. dieses stadium ist daher prädestiniert, um den nachwinterlichen Aktivitätsbeginn zwischen Populationen unterschiedlicher Höhenlagen miteinander zu verglei - chen. -

Medical Problems and Treatment Considerations for the Red Imported Fire Ant

MEDICAL PROBLEMS AND TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE RED IMPORTED FIRE ANT Bastiaan M. Drees, Professor and Extension Entomologist DISCLAIMER: This fact sheet provides a review of information gathered regarding medical aspects of the red imported fire ant. As such, this fact sheet is not intended to provide treatment recommendations for fire ant stings or reactions that may develop as a result of a stinging incident. Readers are encouraged to seek health-related advice and recommendations from their medical doctors, allergists or other appropriate specialists. Imported fire ants, which include the red imported fire ant - Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), the black imported fire ant - Solenopsis richteri Forel and the hybrid between S. invicta and S. richteri, cause medical problems when sterile female worker ants from a colony sting and inject a venom that cause localized sterile blisters, whole body allergic reactions such as anaphylactic shock and occasionally death. In Texas, S. invicta is the only imported fire ant, although several species of native fire ants occur in the state such as the tropical fire ant, S. geminata (Fabricius), and the desert fire ant, S. xyloni McCook, which are also capable of stinging (see FAPFS010 and 013 for identification keys). Over 40 million people live in areas infested by the red imported fire ant in the southeastern United States. An estimated 14 million people are stung annually. According to The Scripps Howard Texas Poll (March 2000), 79 percent of Texans have been stung by fire ants in the year of the survey, while 20% of Texans report not ever having been stung. -

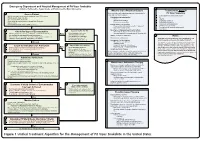

Snake Bite Protocol

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Spider Bites

Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Office of Public Health, Louisiana Dept of Health & Hospitals 800-256-2748 (24 hr number) www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov SPIDER BITES Revised 6/13/2007 Epidemiology There are over 3,000 species of spiders native to the United States. Due to fragility or inadequate length of fangs, only a limited number of species are capable of inflicting noticeable wounds on human beings, although several small species of spiders are able to bite humans, but with little or no demonstrable effect. The final determination of etiology of 80% of suspected spider bites in the U.S. is, in fact, an alternate diagnosis. Therefore the perceived risk of spider bites far exceeds actual risk. Tick bites, chemical burns, lesions from poison ivy or oak, cutaneous anthrax, diabetic ulcer, erythema migrans from Lyme disease, erythema from Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, sporotrichosis, Staphylococcus infections, Stephens Johnson syndrome, syphilitic chancre, thromboembolic effects of Leishmaniasis, toxic epidermal necrolyis, shingles, early chicken pox lesions, bites from other arthropods and idiopathic dermal necrosis have all been misdiagnosed as spider bites. Almost all bites from spiders are inflicted by the spider in self defense, when a human inadvertently upsets or invades the spider’s space. Of spiders in the United States capable of biting, only a few are considered dangerous to human beings. Bites from the following species of spiders can result in serious sequelae: Louisiana Office of Public Health – Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Page 1 of 14 The Brown Recluse: Loxosceles reclusa Photo Courtesy of the Texas Department of State Health Services The most common species associated with medically important spider bites: • Physical characteristics o Length: Approximately 1 inch o Appearance: A violin shaped mark can be visualized on the dorsum (top). -

'Macrovipera Lebetina' Venom Cytotoxicity in Kidney Cell Line HEK

ASIA PACIFIC JOURNAL of MEDICAL TOXICOLOGY APJMT 5;2 http://apjmt.mums.ac.ir June 2016 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evaluation of Iranian snake ‘Macrovipera lebetina’ venom cytotoxicity in kidney cell line HEK-293 HOURIEH ESMAEILI JAHROMI1, ABBAS ZARE MIRAKABADI2, MORTEZA KAMALZADEH3 1 Department of Biology, Payame Noor University (PNU), Tehran, Iran. 2 Department of Venomous Animals and Anti venom Production, Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Karaj, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization (AREEO), Tehran, Iran. 3 Department of Quality control, Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Karaj, Iran. Abstract Background: Envenomation by Macrovipera lebetina (M. lebetina) is characterized by prominent local tissue damage, hemorrhage, abnormalities in the blood coagulation system, necrosis, and edema. However, the main cause of death after a bite by M. lebetina has been attributed to acute renal failure (ARF). It is unclear whether the venom components have a direct or indirect action in causing ARF. To investigate this point, we looked at the in vitro effect of M. lebetina crude venom, using cultured human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) mono layers as a model. Methods: The effect of M. lebetina snake venom on HEK - 293 growth inhibition was determined by the MTT assay and the neutral red uptake assay. The integrity of the cell membrane through LDH release was measured with the Cytotoxicity Detection Kit. Morphological changes in HEK-293 cells were also evaluated using an inverted microscope. Results: In the MTT assay, crude venom showed a significant cytotoxic effect on HEK-293 cells at 24 hours of exposure and was confirmed by the neutral red assay. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

The Venom Produced by Different Classes of Arthropods and Uses It As a Biological Control Agent

Archive of SID The venom produced by different classes of arthropods and uses it as a biological control agent Kabir Eyidozehi1, Sultan Ravan2 1Ph.D. student of Agricultural Entomology, University of Zabol, Iran 2 Associate Professor Plant Protection Department, University of Zabol, Iran (Corresponding Author: Kabir Eyidozehi) Abstract Animal kingdom possesses numerous poisonous species that produce venoms or toxins. The biodiversity of venoms and toxins made it a unique source of leads and structural templates from which new therapeutic agents may be developed. Such richness can be useful to biotechnology and/or pharmacology in many ways, with the prospection of new toxins in this field. Venoms of several animal species such as snakes, scorpions, toads, frogs and their active components have shown potential biotechnological applications. Recently, using molecular biology techniques and advanced methods of fractionation, researchers have obtained different native and/or recombinant toxins and enough material to afford deeper insight into the molecular action of these toxins. Now a day to visualize the boundaries between cancerous tissues and normal tissues florescent labeled scorpion venom peptides are used. Still a lot of peptides in scorpion venom are not identified. Further studies are needed to identify therapeutically crucial peptides in scorpion venom. This paper reviews the knowledge about the various aspects related to the name, biological and medical importance of poisonous animals of different major animal phyla. Key words: Poisonous animals, Scorpion, Spider, Venoms, Insects www.SID.ir Archive of SID INTRODUCTION 1. The biological and medical significance of poisonous animals Animal venoms and toxins are now recognized as major sources of bioactive molecules that may be tomorrow’s new drug leads. -

Micrurus Lemniscatus (Large Coral Snake)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Micrurus lemniscatus (Large Coral Snake) Family: Elapidae (Cobras and Coral Snakes) Order: Squamata (Lizards and Snakes) Class: Reptilia (Reptiles) Fig. 1. Large coral snake, Micrurus leminiscatus. [http://www.flickr.com/photos/lvulgaris/6856842857/, downloaded 4 December 2012] TRAITS. The large snake coral has a triad-type pattern, i.e. the black coloration is in clusters of three. The centre band of the triad is wider than the outer ones and is separated by wide white or yellow rings (Schmidt 1957). The red band is undisturbed and bold and separates the black triads. The snout is black with a white crossband (Fig. 1). The triad number may vary from 9-13 on the body and the tail may have 1-2. The physical shape and the structure of the body of the large coral snake show a resemblance to the colubrids. It is the dentition and the formation of the maxillary bone that distinguishes the two, including the hollow fangs. The largest Micrurus lemniscatus ever recorded was 106.7 cm; adults usually measure from 40-50 cm (Schmidt 1957). The neck is not highly distinguishable from the rest of the body as there is modest narrowing of that area behind the neck giving the snake an almost cylindrical, elongated look. Dangerously venomous. UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour ECOLOGY. The large coral snake is mostly found in South America, east of the Andes, southern Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, the Guianas and Brazil, it is uncommon in Trinidad. -

Venom Protein of the Haematotoxic Snakes Cryptelytrops Albolabris

S HORT REPORT ScienceAsia 37 (2011): 377–381 doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2011.37.377 Venom protein of the haematotoxic snakes Cryptelytrops albolabris, Calloselasma rhodostoma, and Daboia russelii siamensis Orawan Khow, Pannipa Chulasugandha∗, Narumol Pakmanee Research and Development Department, Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute, Patumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand ∗Corresponding author, e-mail: pannipa [email protected] Received 1 Dec 2010 Accepted 6 Sep 2011 ABSTRACT: The protein concentration and protein pattern of crude venoms of three major haematotoxic snakes of Thailand, Cryptelytrops albolabris (green pit viper), Calloselasma rhodostoma (Malayan pit viper), and Daboia russelii siamensis (Russell’s viper), were studied. The protein concentrations of all lots of venoms studied were comparable. The chromatograms, from reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography, of C. albolabris venom and C. rhodostoma venom were similar but they were different from the chromatogram of D. r. siamensis venom. C. rhodostoma venom showed the highest number of protein spots on 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (pH gradient 3–10), followed by C. albolabris venom and D. r. siamensis venom, respectively. The protein spots of C. rhodostoma venom were used as reference proteins in matching for similar proteins of haematotoxic snakes. C. albolabris venom showed more similar protein spots to C. rhodostoma venom than D. r. siamensis venom. The minimum coagulant dose could not be determined in D. r. siamensis venom. KEYWORDS: 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis, reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography, minimum coag- ulant dose INTRODUCTION inducing defibrination 5–7. The venom of D. r. sia- mensis directly affects factor X and factor V of the In Thailand there are 163 snake species, 48 of which haemostatic system 8,9 . -

An in Vivo Examination of the Differences Between Rapid

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An in vivo examination of the diferences between rapid cardiovascular collapse and prolonged hypotension induced by snake venom Rahini Kakumanu1, Barbara K. Kemp-Harper1, Anjana Silva 1,2, Sanjaya Kuruppu3, Geofrey K. Isbister 1,4 & Wayne C. Hodgson1* We investigated the cardiovascular efects of venoms from seven medically important species of snakes: Australian Eastern Brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis), Sri Lankan Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), Javanese Russell’s viper (D. siamensis), Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), Uracoan rattlesnake (Crotalus vegrandis), Carpet viper (Echis ocellatus) and Puf adder (Bitis arietans), and identifed two distinct patterns of efects: i.e. rapid cardiovascular collapse and prolonged hypotension. P. textilis (5 µg/kg, i.v.) and E. ocellatus (50 µg/kg, i.v.) venoms induced rapid (i.e. within 2 min) cardiovascular collapse in anaesthetised rats. P. textilis (20 mg/kg, i.m.) caused collapse within 10 min. D. russelii (100 µg/kg, i.v.) and D. siamensis (100 µg/kg, i.v.) venoms caused ‘prolonged hypotension’, characterised by a persistent decrease in blood pressure with recovery. D. russelii venom (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, i.m.) also caused prolonged hypotension. A priming dose of P. textilis venom (2 µg/kg, i.v.) prevented collapse by E. ocellatus venom (50 µg/kg, i.v.), but had no signifcant efect on subsequent addition of D. russelii venom (1 mg/kg, i.v). Two priming doses (1 µg/kg, i.v.) of E. ocellatus venom prevented collapse by E. ocellatus venom (50 µg/kg, i.v.). B. gabonica, C. vegrandis and B.