Discussion Class 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pope Nicholas II's 1059 Decree

Pope Nicholas’s speech about simony and papal election, 1059 Draft translation by Charles West, September 2019 Source: MGH Concilia VIII, pp. 382-3 (JL 4431a) The Lord Pope Nicholas, presiding over the synod in the Constantinian basilica, said: “We decree that there should be no mercy for the simoniacs to protect their indignity, and we condemn them according to the sanctions of the canons and the decrees of the holy fathers, and we declare with apostolic authority that they should be deposed. About those who were ordained by simoniacs not for money but freely, since this question has now been debated for a very long time, we remove every knot of doubt, so that we permit no one henceforth to hesitate over this decree. Since the poisonous calamity of the simoniac heresy has until now grown up to such an extent that hardly any church can be found that is not corrupted in some part by this disease, we permit those who have been freely ordained already by simoniacs to remain in their orders, according not to the censure of justice but to the perspective of mercy, unless perhaps some fault from their life stands against them according to the canons. There is such a multitude of these people that since we are not able to enforce the rigour of canonical vigour upon them, it is necessary that we incline our spirit for the moment to the zeal of pious condescension. We do this on condition, however, that by the authority of the Apostles Peter and Paul we absolutely forbid that any of our successors should ever take this permission of ours as a rule for themselves or anyone else, since the authority of the ancient fathers did not promulgate this by command or concession, but the great necessity of the time extorted it from us by permission. -

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy

Texas Nepotism Laws Made Easy 2016 Editor Zindia Thomas Assistant General Counsel Texas Municipal League www.tml.org Updated July 2016 Table of Contents 1. What is nepotism? .................................................................................................................... 1 2. What types of local government officials are subject to the nepotism laws? .......................... 1 3. What types of actions are generally prohibited under the nepotism law? ............................... 1 4. What relatives of a public official are covered by the statutory limitations on relationships by consanguinity (blood)? .................................................................................. 1 5. What relationships by affinity (marriage) are covered by the statutory limitations? .............. 2 6. What happens if it takes two marriages to establish the relationship with the public official? ......................................................................................................................... 3 7. What actions must a public official take if he or she has a nepotism conflict? ....................... 3 8. Do the nepotism laws apply to cities with a population of less than 200? .............................. 3 9. May a close relative be appointed to an unpaid position? ....................................................... 3 10. May other members of a governing body vote to hire a person who is a close relative of a public official if the official with the nepotism conflict abstains from deliberating and/or -

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

Stages of Papal Law

Journal of the British Academy, 5, 37–59. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/005.037 Posted 00 March 2017. © The British Academy 2017 Stages of papal law Raleigh Lecture on History read 1 November 2016 DAVID L. D’AVRAY Fellow of the British Academy Abstract: Papal law is known from the late 4th century (Siricius). There was demand for decretals and they were collected in private collections from the 5th century on. Charlemagne’s Admonitio generalis made papal legislation even better known and the Pseudo-Isidorian collections brought genuine decretals also to the wide audience that these partly forged collections reached. The papal reforms from the 11th century on gave rise to a new burst of papal decretals, and collections of them, culminating in the Liber Extra of 1234. The Council of Trent opened a new phase. The ‘Congregation of the Council’, set up to apply Trent’s non-dogmatic decrees, became a new source of papal law. Finally, in 1917, nearly a millennium and a half of papal law was codified by Cardinal Gasparri within two covers. Papal law was to a great extent ‘demand- driven’, which requires explanation. The theory proposed here is that Catholic Christianity was composed of a multitude of subsystems, not planned centrally and each with an evolving life of its own. Subsystems frequently interfered with the life of other subsystems, creating new entanglements. This constantly renewed complexity had the function (though not the purpose) of creating and recreating demand for papal law to sort out the entanglements between subsystems. For various reasons other religious systems have not generated the same demand: because the state plays a ‘papal’ role, or because the units are small, discrete and simple, or thanks to a clear simple blueprint, or because of conservatism combined with a tolerance of some inconsistency. -

Legislating First Cousin Marriage in the Progressive Era

KISSING COUSINS: LEGISLATING FIRST COUSIN MARRIAGE IN THE PROGRESSIVE ERA Lori Jean Wilson Consanguineous or close-kin marriages are older than history itself. They appear in the religious texts and civil records of the earliest known societies, both nomadic and sedentary. Examples of historical cousin-marriages abound. However, one should not assume that consanguineous partnerships are archaic or products of a bygone era. In fact, Dr. Alan H. Bittles, a geneticist who has studied the history of cousin-marriage legislation, reported to the New York Times in 2009 that first-cousin marriages alone account for 10 percent of global marriages.1 As of 2010, twenty-six states in the United States permit first cousin marriage. Despite this legal acceptance, the stigma attached to first-cousin marriage persists. Prior to the mid- nineteenth century, however, the American public showed little distaste toward the practice of first cousin marriage. A shift in scientific opinion emerged in the mid-nineteenth century and had anthropologists questioning whether the custom had a place in western civilization or if it represented a throwback to barbarism. The significant shift in public opinion however, occurred during the Progressive Era as the discussion centered on genetics and eugenics. The American public vigorously debated whether such unions were harmful or beneficial to the children produced by first cousin unions. The public also debated what role individual states, through legislation, should take in restricting the practice of consanguineous marriages. While divergent opinions emerged regarding the effects of first cousin marriage, the creation of healthy children and a better, stronger future generation of Americans remained the primary goal of Americans on both sides of the debate. -

The Returning Warrior and the Limits of Just War Theory

THE RETURNING WARRIOR AND THE LIMITS OF JUST WAR THEORY R.J. Delahunty Professor of Law University of St. Thomas School of Law* In this essay, I seek to explore a Christian tradition that is nei- ther the just war theory nor pacifism. Unlike pacifism, this tradi- tion teaches that war is a necessary and inescapable aspect of the human condition, and that Christians cannot escape from engaging in it. Unlike just war theory, this tradition holds that engaging in war is intrinsically sinful, however justifiable that activity may be considered to be in the light of human law, morality or reason. Mi- chael Walzer captured the essence of this way of thinking in a cele- brated essay on the problem of “dirty hands.”1 Although Walzer’s essay was chiefly about political rather than military action, he rightly observed that there was a strand in Christian reflection that saw killing, whether in a just or unjust war, as defiling or even sin- ful, even if it conformed to moral and legal standards. That tradi- tion, though subordinate, still survives in Christian, especially Lu- theran, thought. The Church’s thought about war and peace went through sever- al phases before finally settling on the just war theory. Throughout much of the Middle Ages, the Church’s approach to war was pri- marily pastoral and unsystematic. Although opinions varied widely depending on the circumstances, the early medieval Church was commonly skeptical of the permissibility of killing in warfare. Ra- ther, the Church at that time tended to the view that killing – even in a just war – was sinful and required penance. -

Martin Luther’S New Doctrine of Salvation That Resulted in a Break from the Catholic Church and the Establishment of Lutheranism

DO NOW WHAT DOES THE WORD REFORM MEAN? WHAT DO YOU THINK IT MEANS REGARDING THE CHURCH? Learning Targets and Intentions of the Lesson I Want Students To: 1. KNOW the significance of Martin Luther’s new doctrine of salvation that resulted in a break from the Catholic church and the establishment of Lutheranism. 2. UNDERSTAND the way humanism and Erasmus forged the Reformation. 3. Analyze (SKILL) how Calvinism replaced Lutheranism as the most dynamic form of Protestantism. Essential Question. What caused the Protestant Reformation? REFORMATION RE FORM TO DO TO MAKE AGAIN BUT DO OVER/MAKE WHAT AGAIN?THE CHURCH! Definitions Protest Reform To express strong To improve by objection correcting errors The Protestant Reformation 5 Problems in the Church • Corruption • Political Conflicts Calls for Reform • John Wycliffe (1330-1384) – Questioned the authority of the pope • Jan Hus (1370-1415) – Criticized the vast wealth of the Church • Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) – Attacked corruption in the Church Corruption • The Church raised money through practices like simony and selling indulgences. Advantages of Buying Indulgences Go Directly to Heaven! • Do not go to Hell! • Do not go to Purgatory! • Get through Purgatory faster! • Do not pass Go! Martin Luther Who was Martin Luther? • Born in Germany in 1483. • After surviving a violent storm, he vowed to become a monk. • Lived in the city of Wittenberg. • Died in 1546. Luther Looks for Reforms • Luther criticized Church practices, like selling indulgences. • He wanted to begin a discussion within the Church about the true path to salvation. • Stresses faith over He nailed his Ninety- works, rejected church Five Theses, or as intermediary. -

MANUAL of POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal

MANUAL OF POLICY Title Nepotism: Public Officials 1512 Legal Authority Approval of the Board of Trustees Page 1 of 2 Date Approved by Board Board Minute Order dated November 26, 2019 I. Purpose The purpose of this policy is to provide provisions regarding nepotism prohibition of public officials as defined by the consanguinity and affinity relationship. II. Policy A. Nepotism Prohibitions Applicable to Public Officials As public officials, the members of the Board of Trustees and the College President are subject to the nepotism prohibitions of Chapter 573 of the Texas Government Code. South Texas College shall not employ any person related within the second degree by affinity (marriage) or within the third degree by consanguinity (blood) to any member of the Board or the College President when the salary, fees, or compensation of the employee is paid from public funds or fees of office. A nepotism prohibition is not applicable to the employment of an individual with the College if: 1) the individual is employed in the position immediately before the election or appointment of the public official to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree; and 2) that prior employment of the individual is continuous for at least: a. 30 days, if the public official is appointed; b. six months, if the public official is elected at an election other than the general election for state and county officers; or c. one year, if the public official is elected at the general election for state and county officers. If an individual whose employment is not subject to the nepotism prohibition continues in a position, the College President or the member of the Board of Trustees to whom the individual is related in a prohibited degree may not participate in any deliberation or voting on the employment, reemployment, change in status, compensation, or dismissal of the individual if that action applies only to the individual and is not taken regarding a bona fide class or category of employees. -

Q. 100: Irreligion: Simony

QUESTION 100 Irreligion: Simony Next we have to consider simony (simonia). And on this topic there are six questions: (1) What is simony? (2) Is it licit to accept money for the sacraments? (3) Is it licit to accept money for spiritual acts? (4) Is it licit to sell things that are connected with what is spiritual? (5) Is it only a ‘favor by the hand’ (munus a manu) that makes for simony, or also a ‘favor by the tongue’ (munus a lingua) and a ‘favor by allegiance’ (munus ab obsequio)? (6) What about the punishment for one who commits simony? Article 1 Is simony “an eager willingness to sell and to buy something spiritual or something connected with what is spiritual”? It seems that simony is not “an eager willingness to sell and to buy something spiritual or something connected with what is spiritual” (simonia non sit studiosa voluntas emendi et vendendi aliquid spirituale vel spirituali annexum) [Legal Experts]: Objection 1: Simony is a certain heresy, since Decretals 1, q. 1 says, “The impious heresy of Macedonius and of those who with him impugn the Holy Spirit is more tolerable than that of those who are guilty of simony. For in their ravings the former claim that the Holy Spirit is a creature and the slave of God the Father and God the Son, whereas the latter make the same Holy Spirit their own slave. For every owner (dominus) sells what he owns if he wants to, whether it be his slave or any other thing that he possesses.” But as is clear from what was said above (q. -

Third Degree of Consanguinity

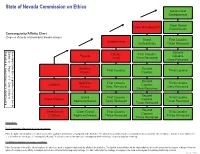

State of Nevada Commission on Ethics Great-Great Grandparents 4 Great Grand Great Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Consanguinity/Affinity Chart 3 5 (Degrees of family relationship by blood/marriage) Grand First Cousins Grandparents Uncles/Aunts Twice Removed 2 4 6 Second Uncles First Cousins Parents Cousins Aunts Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 Brothers Second First Cousins Third Cousins Sisters Cousins 2 4 6 8 Second Nephews First Cousins Third Cousins Children Cousins Nieces Once Removed Once Removed 1 3 5 Once Removed 7 9 Second Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Grand Children Cousins Nephews/Nieces Twice Removed Twice Removed 1 2 4 6 Twice Removed 8 0 Second Great Grand Great Grand First Cousins Third Cousins Cousins Children Nephews/Nieces Thrice Removed Thrice Removed 1 3 5 7 Thrice Removed 9 1 Instructions: For Consanguinity (relationship by blood) calculations: Place the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by consanguinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the public officer/employee. Anyone in a box numbered 1, 2, or 3 is within the third degree of consanguinity. Nevada Ethics in Government Law addresses consanguinity within third degree by blood, adoption or marriage. For Affinity (relationship by marriage) calculations: Place the spouse of the public officer/employee for whom you need to establish relationship by affinity in the blank box. The labeled boxes will then list the relationships by title to the spouse and the degree of distance from the public officer/employee by affinity. A husband and wife are related in the first degree by marriage. -

Documents, Part VIII

Sec. viIi CONTENTS vIiI–1 PART VIII. GLOSSATORS: MARRIAGE CONTENTS A. GRATIAN OF BOLOGNA, CONCORDANCE OF DISCORDANT CANONS, C.27 q.2 .............VIII–2 B. PETER LOMBARD, FOUR BOOKS OF SENTENCES, 4.26–7 ...................................................VIII–12 C. DECRETALS OF ALEXANDER III (1159–1181) AND INNOCENT III (1198–1216) 1B. Veniens ... (before 1170), ItPont 3:404 .....................................................................................VIII–16 2. Sicut romana (1173 or 1174), 1 Comp. 4.4.5(7) ..........................................................................VIII–16 3. Ex litteris (1175 X 1181), X 4.16.2..............................................................................................VIII–16 4. Licet praeter solitum (1169 X 1179, probably 1176 or1177), X 4.4.3.........................................VIII–17 5. Significasti (1159 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.4.6(8)..............................................................................VIII–18 6 . Sollicitudini (1166 X 1181), 1 Comp. 4.5.4(6) ............................................................................VIII–19 7 . Veniens ad nos (1176 X 1181), X 4.1.15 .....................................................................................VIII–19 8m. Tuas dutu (1200) .......................................................................................................................VIII–19 9 . Quod nobis (1170 or 1171), X 4.3.1 ............................................................................................VIII–19 10 . Tuae nobis -

The Falsification of History, Especially in Reference to the Reformation and the Characters of the Reformers, As Pertinacious

“THE FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY, ESPECIALLY IN REFERENCE TO THE REFORMATION AND THE CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMERS, AS PERTINACIOUSLY REPEATED BY THE ADVOCATES OF RITUALISM.” Church Association Tract 12 BY THE REV. T. P. BOULTBEE, M.A., LL.D., PRINCIPAL OF ST JOHN’S HALL, THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE, HIGHBURY, MIDDLESEX. “WOE unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness; that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter. Woe unto them . which justify the wicked for reward, and take away the righteousness of the righteous from him.” What darkness is like the darkness of bewildering falsehood, and what light is like the truth? Once One walked this earth who called Himself “The Truth.’’ Brightly beamed the full-orbed face of that Eternal Truth on the world’s darkness. But around Him surged the legions of that opposite who is called “the father of lies;” the traitor practised his treason; and “false witness was sought to put Him to death.” Calm and silent the august face of the Truth gleamed through the falsehood. But the gathering lies prevailed. Affixed to the accursed cross, the Truth Himself expired, and all was dark. “The sun was darkened,” and “there was darkness over all the earth.” And so He who was the Truth was laid in the tomb, and the power of falsehood prevailed in its final triumph. Nay! this was the very victory of the Truth of God! The blood did but seal the covenant. “Every promise of God was now yea and amen in Christ Jesus.” “A testament is of force after men are dead,” and now no power of Satan’s utmost lie can break the bond.