Legislative Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S. House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guppy Color Strains

Guppy Color Strains Guppy Color Strains Philip Shaddock Third Edition June 2012 v | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | v Guppy Color Strains © 2000 - 2012 Philip Shaddock This book is copyrighted and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. If you wish to quote more than a few lines from the book or use any of its fig- ures, graphics or images, please contact Philip Shaddock through the Guppy Designer website: www.guppydesigner.com. If you find inaccuracies or mistakes in the book, please contact Philip Shaddock through the Guppy Designer site. Your help would be very much appreciated. Contact Philip Shaddock at: www.guppydesigner.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 978-0-9865700-0-1 v | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | v Contents Preface 13 1 Moscows 17 The Moscow in the Rest of the World . 18 Moscow Color and Genetics . 19 Breeding the Moscow . 21 Blue Moscow . 23 Albino Blue Moscow . 24 Blond Blue Moscow . 24 Asian Blau Blue Moscow . 25 Golden Blue Moscow . 26 Green Moscow . 27 Purple Moscow . 27 Full Red Moscow . 28 Half-Black Red Moscow . 29 Albino Full Red Moscow . 30 Golden Red Moscow . 31 Midnight Black Moscow . 31 Albino Midnight Black . 33 Golden Midnight Black . 34 Half Black Moscow . 34 Stoerzbach Moscow . 36 Pink White Moscow . 37 vivii | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | viivi Full Gold Moscow . 38 Blue Grass Moscow . 39 Leopard (Grass) Moscow . 40 Carnation Moscow . 41 Moscow Fire Tail . 43 WREA Full Pearl Moscow . 43 2 Metal Heads 45 Cobra Metal Heads . -

July 2009 1663 Los Alamos Science and Technology Magazine July 2009 the Complicated Network of Transmission a Very Chilly –300°F, to Become Superconducting

loslos alamos alamos science science and and technology technology magazine magazine JUJULYLY 20 20 09 09 Wired for the Future Cyber Wars Have SQUIDs, Will Travel 1663 A Trip to Nuclear North Korea About Our Name: during World War ii, all that the 1663outside world knew of los alamos and its top-secret table of contents laboratory was the mailing address—P. o. Box 1663, santa Fe, new mexico. that box number, still part of our address, symbolizes our historic role in the nation’s from terry wallace service. PrINcIPaL aSSocIatE DIrEctor For ScIENcE, tEchNoLogy, aND ENgINEErINg located on the high mesas of northern new mexico, los alamos national laboratory was founded in 1943 to build the first atomic bomb. it remains a premier scientific laboratory, dedicated to national security in its broadest the Scientist Envoy INSIDE FroNt coVEr sense. the laboratory is operated by los alamos national security, llc, for the department of energy’s national nuclear security administration. features About the Cover: artist’s conception of a hacker’s “trojan horse,” in cyberspace. los alamos fights an mosArchive unending battle against trojan horses, worms, and la other forms of malicious software but is spearheading LosA research to play offense rather than defense in the Wired for the Future 2 During the Manhattan Project, Enrico Fermi, Nobel Laureate and leader of SUPErcoNDUctINg WIrES MIght traNSForM ENErgy DIStrIBUtIoN ongoing cyber wars. F-Division, meets with San Ildefonso Pueblo’s Maria Martinez, famous worldwide for her extraordinary black pottery. from terry wallace cyber Wars The Scientist Envoy 6 thE UNENDINg BATTLE For coNtroL Since the middle of the His direct experience with both plutonium metallurgy nineteenth century and the and international diplomacy have allowed him to days of Mendeleev, Darwin, communicate with the North’s weapons scientists, Pasteur, and Maxwell, obtain accurate information about the country’s scientists have helped to plutonium capabilities, and report his findings to the have SQUIDs, Will travel 12 better society. -

The Mining Law Review

The Mining Law Review Fifth Edition Editor Erik Richer La FlÈche Law Business Research The Mining Law Review Fifth Edition Editor Erik Richer La FlÈche Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Gideon Roberton SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Thomas Lee SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGERS Felicity Bown, Joel Woods ACCOUNT MANAGERS Jessica Parsons, Jesse Rae Farragher MARKETING COORDINATOR Rebecca Mogridge EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Gavin Jordan HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Claire Ancell SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Paul Howarth Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2016 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided is accurate as of October 2016, be advised that this is a developing area. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to Law Business Research, at the address above. Enquiries concerning editorial content should be directed to the Publisher – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-910813-30-0 Printed in Great Britain by Encompass Print Solutions, -

Enhancement of Udc Data for Use and Sharing in A

Enhancement of UDC data for use and sharing in a networked environment: [presentation at the Librarian Workshop in conjunction with "The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications", March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany] Item Type Presentation Authors Slavic, Aida; Cordeiro, Maria Inês; Riesthuis, Gerhard Citation Enhancement of UDC data for use and sharing in a networked environment: [presentation at the Librarian Workshop in conjunction with "The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications", March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany] 2007, Download date 02/10/2021 10:10:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105770 Librarian Workshop 8 March 2007 The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications, March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany ENHANCEMENT OF UDC DATA FOR USE AND SHARING IN A NETWORKED ENVIRONMENT Aida Slavic Maria Ines Cordeiro Gerhard Riesthuis MAIN POINTS UDC facts update Logic behind the synthetic structure UDC number building and authority control Improvement of data Data development roadmap UNIVERSAL DECIMAL CLASSIFICATION (UDC) classification system created to support • detailed document indexing in bibliographies • broad collocation of subject vocabulary – current database “UDC MRF - Master Reference File” contains 67.600 classes covers the whole universe of knowledge hierarchical, analytico-synthetic, -

Mining Law Trends

Denver Law Review Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 13 February 2021 Mining Law Trends H. Byron Mock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation H. Byron Mock, Mining Law Trends, 54 Denv. L.J. 567 (1977). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Denver Law Review at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. MINING LAW TRENDS By H. BYRON MOCK* INTRODUCTION Bob Clark, Phil Hoff, and two other colleagues included a fine and well-reasoned caveat in the report of the Public Land Law Review commission.' I have too much respect for their opin- ions to challenge them without quite a bit of thought. However, they adopt the basic premise that the Mineral Lands Leasing System is so good that it will accomplish all things. Mineral leasing will supposedly fill our need for energy and resource devel- opment, provide for the opportunity for the creation of new wealth, and make it economically possible to develop new mines. But it just isn't so. The Mining Law of 18722 is so continually under this kind of attack, there must be something good about it.3 How else can we * Partner in Mock, Shearer, and Carling and President, Mineral Records, Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah. PUBLIC LAND LAW REVIEW COMMISSION, ONE THIRD OF THE NATION'S LAND 130, 132 (1970) [hereinafter cited as PLLRC REPORT]. -

Modern Mining Needs a Modern Mining Law

EARTHWORKS FACTSHEET Modern Mining Needs a Modern Mining Law Pollution and Taxpayer Liability at Modern Mines Demonstrate that the Existing Patchwork of Laws does not Adequately Protect Communities and their Water The hardrock mining industry argues that pollution from mines result almost entirely from historic operations. “Modern” mines, the industry argues, are governed by numerous statutes and regulations and are environmentally responsible, problem-free operations.1 Unfortunately, the assertion that that all modern mines are clean, is simply not true. Consider: • A 2006 peer-reviewed study of modern mines revealed that more than 75% of the mines reviewed exceeded water quality standards.2 • At least 16 modern mines have gone bankrupt.3 • Unfunded taxpayer liability at currently operating mines probably exceeds $12 billion.4 It is true that historic mining polluted and continues to pollute rivers, streams and aquifers. Until 1976, there were no federal regulations written specifically to govern hardrock mining operations on publicly owned land. But, it is also clear from the issues at modern mines that the patchwork of laws that govern hardrock mining operations are not enough to ensure that western watersheds and communities are protected. Mines that began operations in the past three decades – three decades in which the mining industry was governed by modern environmental laws – have spilled cyanide, killed aquatic life, caused pollution that will require treatment in perpetuity and burdened the taxpayers with enormous liabilities. Many Modern Mines Exceed Current Water Quality Standards In order to be permitted, a proposed mine must predict that it will comply with applicable environmental standards. At the time they are permitted, all modern mining operations predict that they will comply with applicable standards during and after mining operations. -

EPA's National Hardrock Mining Framework

EPA’s National Hardrock Mining Framework U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water (4203) 401 M Street, SW Washington, DC 20460 HARDROCK MINING FRAMEWORK September 1997 September 1997 HARDROCK MINING FRAMEWORK Table of Contents 1.0 Purpose and Organization of the Framework ...................................1 1.1 Purpose of the Hardrock Mining Framework ..............................1 1.2 Why Develop an EPA National Mining Framework Now? ....................1 1.2.1 Need For Program Integration ...................................1 1.2.2 The Environmental Impacts of Mining .............................1 1.3 Goals of EPA’s Mining Framework .....................................3 1.4 Guide to the Framework ..............................................3 2.0 Current Status ..........................................................3 2.1 Overview of Regulatory Framework for Mining ............................3 2.2 EPA Statutory Authority .............................................4 2.3 Partnerships .......................................................6 3.0 Improving How We Do Business ...........................................7 3.1 Key Considerations .................................................7 3.2 Recommendations ..................................................8 4.0 Implementation Actions .................................................10 4.1 Putting the Framework into Action .....................................10 4.2 Next Steps .......................................................11 5.0 Introduction to the Appendices -

MINING in NATIONAL FORESTS Protection of Surface Resources 1

MINING IN NATIONAL FORESTS Protection of Surface Resources 1 Mineral Resources of the National Forest System The 192-million-acre National Forest System is an important part of the Nation’s resource base. As directed by the Organic Administration Act of 1897 and the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960, the National Forests are managed by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service for continuous production of their renewable resources – timber, clean water, wildlife habitat, forage for livestock and outdoor recreation. Although not renewable, minerals are also important resources of the National Forests. In fact, they are vital to the Nation’s welfare. By accident of category and geology, the National Forests contain much of the country’s remaining stores of mineral – prime examples being the National Forests of the Rocky Mountains, the Basin and Range Province, the Cascade-Sierra Nevada Ranges, the Alaska Coast range, and the States of Missouri, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Less known by apparently good mineral potential exists in the southern and eastern National Forests. Geologically, National Forest System lands contain some of the most favorable host rocks for mineral deposits. Approximately 6.5 million acres are known to be underlain by coal. Approximately 45 million acres or one-quarter of National Forest System lands have potential for oil and gas, while about 300,000 acres within the Pacific Coast and Great Basin States have potential for geothermal resource development. Within the past few years, the energy shortage in this country has reminded us that the Nation’s mineral resources are limited. As with oil supplies, there will undoubtedly be tightening of world supplies of minerals. -

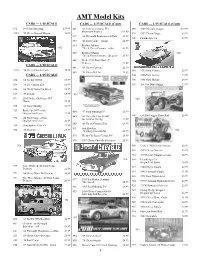

AMT Model Kits

AMT Model Kits CARS — 1/16 SCALE CARS — 1/25 SCALE (Cont) CARS — 1/25 SCALE (Cont) 872 1965 Ford Mustang $39.99 841 2013 Chevy Camaro ZL1 898 1969 Mercury Cougar $22.99 Showroom Replica $21.99 1005 ‘55 Chevy Nomad Wagon 38.99 899 1937 Chevy Coupe 24.99 849 ‘68 Plymouth Roadrunner-yellow 23.99 900 Piranha Spy Car 23.99 850 ‘40 Ford Coupe—orange 22.99 , 854 Baldwin Motion 872 ‘70 1/2 Chevy Camaro—white 21.99 855 Baldwin Motion 900 ‘70 1/2 Chevy Camaro—dk green 21.99 860 Nestle 1923 Ford Model T Delivery 23.99 CARS — 1/20 SCALE 861 ‘63 Chevy Corvette 22.99 1030 ‘94 Chevy Camaro Conv. 26.99 902 1932 Ford Victoria 25.99 862 ‘51 Chevy Bel Air 21.99 CARS — 1/25 SCALE 904 1966 Ford Galaxie 23.99 634 ‘68 Shelby GT500 15.99 906 1941 Ford Woody 24.99 635 ‘70 1/2 Camaro Z28 15.99 907 Tee Vee Dune Buggy 23.99 636 ‘66 Chevy Nova Pro Street 15.99 638 ‘57 Bel Air 15.99 862 671 2010 Dodge Challenger R/T 907 Classic 19.99 704 ‘66 Ford Mustang 21.99 729 Buick Opel GT- white 864 ‘97 Ford Mustang GT 21.99 Original Art Series 24.99 865 ‘62 Chevy Bel Air SS 409 908 Li’l Hot Dogger Show Rod 26.99 730 ‘40 Ford Coupe –white Joe Gardner Racing 22.99 Original Art Series 22.99 868 ‘68 Chevy Camaro Z/28 21.99 750 Ghostbusters Ecto-1A 22.99 871 Jack Reacher 768 ‘75 Gremlin 21.99 ‘70 Chevy Chevelle SS 23.99 908 873 Chevy CheZoom Corvair F/C 24.99 876 1967 Chevy Chevelle Pro Street 21.99 768 909 USA-1 1963 Chevy Corvette 22.99 910 1953 Chevy Corvette 23.99 912 ‘69 Mercury Cougar—orange 22.99 876 916 Piranha Spy Car Original Art Series 26.99 769 Gene Winfield ‘40 Ford Sedan 917 1964 Chevy Impala 22.99 Delivery 22.99 919 1941 Plymouth Coupe 21.99 772 ‘66 Chevy Nova-Bill Jenkins 24.99 920 1971 Ford Thunderbird 25.99 791 The Three Stooges ‘40 Ford Sedan 877 1953 Studebaker Starliner Delivery 22.99 “Mr. -

What Is Natural Resources Law?

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2007 What Is Natural Resources Law? Robert L. Fischman Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation Fischman, Robert L., "What Is Natural Resources Law?" (2007). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 197. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT IS NATURAL RESOURCES LAW? ROBERT L. FISCHMAN* INTRODUCTION Natural resources law is a field with divided loyalties. It has one foot in statutory, administrative law and the other in common law property. Within the ambit of environmental con- cerns, management of natural resources looms large. It can justifiably claim an important role in any course of study in en- vironmental law. Similarly, any advanced property curriculum ought to consider the myriad forms of rights and allocative schemes in natural resources law. Yet, many practitioners and professors identify themselves as specialists in the field of natural resources, rather than in a natural resources sub- specialty of environmental or property law. Indeed, this analy- sis began as a contribution to a panel discussion sponsored by the natural resources law section, which is separate from the environmental law section, of the Association of American Law Schools. -

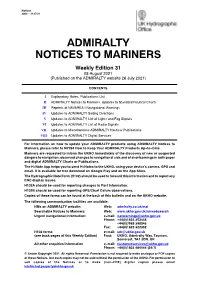

Weekly Edition 31 of 2021

Notices 3062 -- 3147/21 ADMIRALTY NOTICES TO MARINERS Weekly Edition 31 05 August 2021 (Published on the ADMIRALTY website 26 July 2021) CONTENTS I Explanatory Notes. Publications List II ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners. Updates to Standard Nautical Charts III Reprints of NAVAREA I Navigational Warnings IV Updates to ADMIRALTY Sailing Directions V Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Lights and Fog Signals VI Updates to ADMIRALTY List of Radio Signals VII Updates to Miscellaneous ADMIRALTY Nautical Publications VIII Updates to ADMIRALTY Digital Services For information on how to update your ADMIRALTY products using ADMIRALTY Notices to Mariners, please refer to NP294 How to Keep Your ADMIRALTY Products Up--to--Date. Mariners are requested to inform the UKHO immediately of the discovery of new or suspected dangers to navigation, observed changes to navigational aids and of shortcomings in both paper and digital ADMIRALTY Charts or Publications. The H--Note App helps you to send H--Notes to the UKHO, using your device’s camera, GPS and email. It is available for free download on Google Play and on the App Store. The Hydrographic Note Form (H102) should be used to forward this information and to report any ENC display issues. H102A should be used for reporting changes to Port Information. H102B should be used for reporting GPS/Chart Datum observations. Copies of these forms can be found at the back of this bulletin and on the UKHO website. The following communication facilities are available: NMs on ADMIRALTY website: Web: admiralty.co.uk/msi Searchable Notices to Mariners: Web: www.ukho.gov.uk/nmwebsearch Urgent navigational information: e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 353448 +44(0)7989 398345 Fax: +44(0)1823 322352 H102 forms e--mail: [email protected] (see back pages of this Weekly Edition) Post: UKHO, Admiralty Way, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2DN, UK All other enquiries/information e--mail: [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1823 484444 (24/7) Crown Copyright 2021. -

What Is Natural Resources Law? Robert L

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2007 What Is Natural Resources Law? Robert L. Fischman Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation Fischman, Robert L., "What Is Natural Resources Law?" (2007). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 197. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT IS NATURAL RESOURCES LAW? ROBERT L. FISCHMAN* INTRODUCTION Natural resources law is a field with divided loyalties. It has one foot in statutory, administrative law and the other in common law property. Within the ambit of environmental con- cerns, management of natural resources looms large. It can justifiably claim an important role in any course of study in en- vironmental law. Similarly, any advanced property curriculum ought to consider the myriad forms of rights and allocative schemes in natural resources law. Yet, many practitioners and professors identify themselves as specialists in the field of natural resources, rather than in a natural resources sub- specialty of environmental or property law. Indeed, this analy- sis began as a contribution to a panel discussion sponsored by the natural resources law section, which is separate from the environmental law section, of the Association of American Law Schools.