Generations of Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Guppy Color Strains

Guppy Color Strains Guppy Color Strains Philip Shaddock Third Edition June 2012 v | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | v Guppy Color Strains © 2000 - 2012 Philip Shaddock This book is copyrighted and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. If you wish to quote more than a few lines from the book or use any of its fig- ures, graphics or images, please contact Philip Shaddock through the Guppy Designer website: www.guppydesigner.com. If you find inaccuracies or mistakes in the book, please contact Philip Shaddock through the Guppy Designer site. Your help would be very much appreciated. Contact Philip Shaddock at: www.guppydesigner.com 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 978-0-9865700-0-1 v | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | v Contents Preface 13 1 Moscows 17 The Moscow in the Rest of the World . 18 Moscow Color and Genetics . 19 Breeding the Moscow . 21 Blue Moscow . 23 Albino Blue Moscow . 24 Blond Blue Moscow . 24 Asian Blau Blue Moscow . 25 Golden Blue Moscow . 26 Green Moscow . 27 Purple Moscow . 27 Full Red Moscow . 28 Half-Black Red Moscow . 29 Albino Full Red Moscow . 30 Golden Red Moscow . 31 Midnight Black Moscow . 31 Albino Midnight Black . 33 Golden Midnight Black . 34 Half Black Moscow . 34 Stoerzbach Moscow . 36 Pink White Moscow . 37 vivii | Table of Contents Guppy Color STrains | viivi Full Gold Moscow . 38 Blue Grass Moscow . 39 Leopard (Grass) Moscow . 40 Carnation Moscow . 41 Moscow Fire Tail . 43 WREA Full Pearl Moscow . 43 2 Metal Heads 45 Cobra Metal Heads . -

July 2009 1663 Los Alamos Science and Technology Magazine July 2009 the Complicated Network of Transmission a Very Chilly –300°F, to Become Superconducting

loslos alamos alamos science science and and technology technology magazine magazine JUJULYLY 20 20 09 09 Wired for the Future Cyber Wars Have SQUIDs, Will Travel 1663 A Trip to Nuclear North Korea About Our Name: during World War ii, all that the 1663outside world knew of los alamos and its top-secret table of contents laboratory was the mailing address—P. o. Box 1663, santa Fe, new mexico. that box number, still part of our address, symbolizes our historic role in the nation’s from terry wallace service. PrINcIPaL aSSocIatE DIrEctor For ScIENcE, tEchNoLogy, aND ENgINEErINg located on the high mesas of northern new mexico, los alamos national laboratory was founded in 1943 to build the first atomic bomb. it remains a premier scientific laboratory, dedicated to national security in its broadest the Scientist Envoy INSIDE FroNt coVEr sense. the laboratory is operated by los alamos national security, llc, for the department of energy’s national nuclear security administration. features About the Cover: artist’s conception of a hacker’s “trojan horse,” in cyberspace. los alamos fights an mosArchive unending battle against trojan horses, worms, and la other forms of malicious software but is spearheading LosA research to play offense rather than defense in the Wired for the Future 2 During the Manhattan Project, Enrico Fermi, Nobel Laureate and leader of SUPErcoNDUctINg WIrES MIght traNSForM ENErgy DIStrIBUtIoN ongoing cyber wars. F-Division, meets with San Ildefonso Pueblo’s Maria Martinez, famous worldwide for her extraordinary black pottery. from terry wallace cyber Wars The Scientist Envoy 6 thE UNENDINg BATTLE For coNtroL Since the middle of the His direct experience with both plutonium metallurgy nineteenth century and the and international diplomacy have allowed him to days of Mendeleev, Darwin, communicate with the North’s weapons scientists, Pasteur, and Maxwell, obtain accurate information about the country’s scientists have helped to plutonium capabilities, and report his findings to the have SQUIDs, Will travel 12 better society. -

On Our Short List

et al.: On Our Short List ~~~ ~ - - ~ ·. ij ·~ .l.tist AARON SORKIN ' 83 Broadway Brat rticles about the Broadway courtroom drama, A Few Good Men, tend to focus on its playwright, newcomer Aaron Sor Akin. But he's only half the story. Ina year when producers are playing it safe by mounting revivals like Gypsy, the eagerness to produce Sorkin's 21-character piece and the speed with which Hollywood snapped up the story were, well, dramatic. Broadway patrons flocked to Sorkin's 63- scene play. No less than six powerful produc ers brought Sorkin's show to Broadway for a price tag of more than three-quarters of a mil lion dollars. Among them are film producer David Brown (Jaws) and members of the Shubert Organization. Critics have showered the show with praise. "The greatest courtroom drama since The Caine Mutiny Court Martial," said one. Another pronounced it the best American play of the year. Masterful performances by Tom Hulce, Stephen Lang, and an ensemble cast guarantee recognition when the Tony Awards are announced this spring. Sorkin makes his job sound simple. He told James Servin of the New York weekly Seven Days, explaining his blueprint for the ideal script: "Somebody wants something. Something stands in their way of getting it, and somehow the obstacle must be over come. It's the Aristotelian principle." Sorkin's own Aristotelian ascent was by no means instantaneous. He came to New York in 1983, fresh from Syracuse with an under graduate degree in drama. At first he was a runner for the TKTS booth on Times Square, then a theater bartender. -

Enhancement of Udc Data for Use and Sharing in A

Enhancement of UDC data for use and sharing in a networked environment: [presentation at the Librarian Workshop in conjunction with "The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications", March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany] Item Type Presentation Authors Slavic, Aida; Cordeiro, Maria Inês; Riesthuis, Gerhard Citation Enhancement of UDC data for use and sharing in a networked environment: [presentation at the Librarian Workshop in conjunction with "The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications", March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany] 2007, Download date 02/10/2021 10:10:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105770 Librarian Workshop 8 March 2007 The 31st Annual Conference of the German Classification Society on Data Analysis, Machine Learning, and Applications, March 7-9, 2007, Freiburg i. Br., Germany ENHANCEMENT OF UDC DATA FOR USE AND SHARING IN A NETWORKED ENVIRONMENT Aida Slavic Maria Ines Cordeiro Gerhard Riesthuis MAIN POINTS UDC facts update Logic behind the synthetic structure UDC number building and authority control Improvement of data Data development roadmap UNIVERSAL DECIMAL CLASSIFICATION (UDC) classification system created to support • detailed document indexing in bibliographies • broad collocation of subject vocabulary – current database “UDC MRF - Master Reference File” contains 67.600 classes covers the whole universe of knowledge hierarchical, analytico-synthetic, -

Hello, My Name Is Igor and I Am a Russian by Birth. I Have Read A

Added 31 Jan 2000 "Hello, My name is Igor and I am a Russian by birth. I have read a lot about Islam, I have Arabic and Chechen friends and I read a lot about the Holy Koran and its teaching. I resent the drunkenness and stupidity of the Russian society and especially the gorrilla soldiers that are fighting against the noble Mujahideen in Chechnya. I would like to become a Muslim and in connection with this I would like to ask you to give me some guidance. Where do I go in Moscow for help in becoming a Muslim. Inshallah I can accomplish this with your help." [Igor, Moscow, Russia, 28 Jan 2000] "May Allah help you brothers. I am from Kuwait. All Kuwaitis are with you. We hope for you to win this war, inshallah very soon. If you want me to do anything for you, please tell me. I really feel ashamed sitting in Kuwait and you brothers are fighting the kuffar (disbelievers). Please tell me if we can come there with you, can we come?" [Brothers R and R, Kuwait, 30 Jan 2000] "Salam my Brave Mujahadeen who are fighting in Chechnya and the ones administrating this web site. Every day I come to this site several time just to catch a glimpse of the beautiful faces whom Allah has embraced shahadah and to get the latest news. I envy you O Mujahadeen, tears run into my eyes every time I hear any news and see any faces on this site. My beloved brothers, Allah has chosen you to reawaken Muslims around the world. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

From Weaklings to Wounded Warriors: the Changing Portrayal of War-Related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in American Cinema

49th Parallel, Vol. 30 (Autumn 2012) ISSN: 1753-5794 (online) Maseda/ Dulin From Weaklings to Wounded Warriors: The Changing Portrayal of War-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in American Cinema Rebeca Maseda, Ph.D and Patrick L. Dulin, Ph.D* University of Alaska Anchorage “That which doesn’t kill me, can only make me stronger.”1 Nietzche’s manifesto, which promises that painful experiences develop nerves of steel and a formidable character, has not stood the test of time. After decades of research, we now know that traumatic events often lead to debilitating psychiatric symptoms, relationship difficulties, disillusionment and drug abuse, all of which have the potential to become chronic in nature.2 The American public is now quite familiar with the term Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), its characteristics and associated problems. From what we know now, it would have been more appropriate for Nietzche to have stated “That which doesn’t kill me sometimes makes me stronger, sometimes cripples me completely, but regardless, will stay with me until the end of my days.” The effects of trauma have not only been a focus of mental health professionals, they have also captured the imagination of Americans through exposure to cultural artefacts. Traumatized veterans in particular have provided fascinating material for character development in Hollywood movies. In many film representations the returning veteran is violent, unpredictable and dehumanized; a portrayal that has consequences for the way veterans are viewed by U.S. society. Unlike the majority of literature stemming from trauma studies that utilizes Freudian * Dr Maseda works in the Department of Languages at the University of Alaska, Anchorage, and can be reached at [email protected]. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

Each Cadet Squadron Is Sponsored by an Active Duty Unit. Below Is The

Each Cadet Squadron is sponsored by an Active Duty Unit. Below is the listing for the Cadet Squadron and the Sponsor Unit CS SPONSOR WING BASE MAJCOM 1 1st Fighter Wing 1 FW Langley AFB VA ACC 2 388th Fighter Wing 388 FW Hill AFB UT ACC 3 60th Air Mobility Wing 60 AMW Travis AFB CA AMC 4 15th Wing 15 WG Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam PACAF 5 12th Flying Training Wing 12 FTW Randolph AFB TX AETC 6 4th Fighter Wing 4 FW Seymour Johonson AFB NC ACC 7 49th Fighter Wing 49 FW Holloman AFB NM ACC 8 46th Test Wing 46 TW Eglin AFB FL AFMC 9 23rd Wing 23 WG Moody AFB GA ACC 10 56th Fighter Wing 56 FW Luke AFB AZ AETC 11 55th Wing AND 11th Wing 55WG AND 11WG Offutt AFB NE AND Andrews AFB ACC 12 325th Fighter Wing 325 FW Tyndall AFB FL AETC 13 92nd Air Refueling Wing 92 ARW Fairchild AFB WA AMC 14 412th Test Wing 412 TW Edwards AFB CA AFMC 15 355th Fighter Wing 375 AMW Scott AFB IL AMC 16 89th Airlift Wing 89 AW Andrews AFB MD AMC 17 437th Airlift Wing 437 AW Charleston AFB SC AMC 18 314th Airlift Wing 314 AW Little Rock AFB AR AETC 19 19th Airlift Wing 19 AW Little Rock AFB AR AMC 20 20th Fighter Wing 20 FW Shaw AFB SC ACC 21 366th Fighter Wing AND 439 AW 366 FW Mountain Home AFB ID AND Westover ARB ACC/AFRC 22 22nd Air Refueling Wing 22 ARW McConnell AFB KS AMC 23 305th Air Mobility Wing 305 AMW McGuire AFB NJ AMC 24 375th Air Mobility Wing 355 FW Davis-Monthan AFB AZ ACC 25 432nd Wing 432 WG Creech AFB ACC 26 57th Wing 57 WG Nellis AFB NV ACC 27 1st Special Operations Wing 1 SOW Hurlburt Field FL AFSOC 28 96th Air Base Wing AND 434th ARW 96 ABW -

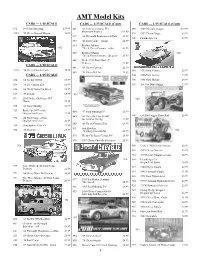

AMT Model Kits

AMT Model Kits CARS — 1/16 SCALE CARS — 1/25 SCALE (Cont) CARS — 1/25 SCALE (Cont) 872 1965 Ford Mustang $39.99 841 2013 Chevy Camaro ZL1 898 1969 Mercury Cougar $22.99 Showroom Replica $21.99 1005 ‘55 Chevy Nomad Wagon 38.99 899 1937 Chevy Coupe 24.99 849 ‘68 Plymouth Roadrunner-yellow 23.99 900 Piranha Spy Car 23.99 850 ‘40 Ford Coupe—orange 22.99 , 854 Baldwin Motion 872 ‘70 1/2 Chevy Camaro—white 21.99 855 Baldwin Motion 900 ‘70 1/2 Chevy Camaro—dk green 21.99 860 Nestle 1923 Ford Model T Delivery 23.99 CARS — 1/20 SCALE 861 ‘63 Chevy Corvette 22.99 1030 ‘94 Chevy Camaro Conv. 26.99 902 1932 Ford Victoria 25.99 862 ‘51 Chevy Bel Air 21.99 CARS — 1/25 SCALE 904 1966 Ford Galaxie 23.99 634 ‘68 Shelby GT500 15.99 906 1941 Ford Woody 24.99 635 ‘70 1/2 Camaro Z28 15.99 907 Tee Vee Dune Buggy 23.99 636 ‘66 Chevy Nova Pro Street 15.99 638 ‘57 Bel Air 15.99 862 671 2010 Dodge Challenger R/T 907 Classic 19.99 704 ‘66 Ford Mustang 21.99 729 Buick Opel GT- white 864 ‘97 Ford Mustang GT 21.99 Original Art Series 24.99 865 ‘62 Chevy Bel Air SS 409 908 Li’l Hot Dogger Show Rod 26.99 730 ‘40 Ford Coupe –white Joe Gardner Racing 22.99 Original Art Series 22.99 868 ‘68 Chevy Camaro Z/28 21.99 750 Ghostbusters Ecto-1A 22.99 871 Jack Reacher 768 ‘75 Gremlin 21.99 ‘70 Chevy Chevelle SS 23.99 908 873 Chevy CheZoom Corvair F/C 24.99 876 1967 Chevy Chevelle Pro Street 21.99 768 909 USA-1 1963 Chevy Corvette 22.99 910 1953 Chevy Corvette 23.99 912 ‘69 Mercury Cougar—orange 22.99 876 916 Piranha Spy Car Original Art Series 26.99 769 Gene Winfield ‘40 Ford Sedan 917 1964 Chevy Impala 22.99 Delivery 22.99 919 1941 Plymouth Coupe 21.99 772 ‘66 Chevy Nova-Bill Jenkins 24.99 920 1971 Ford Thunderbird 25.99 791 The Three Stooges ‘40 Ford Sedan 877 1953 Studebaker Starliner Delivery 22.99 “Mr. -

Executive Airlift Aircraft Maintenance and Back Shop Support

EXECUTIVE AIRLIFT AIRCRAFT MAINTENANCE AND BACK SHOP SUPPORT COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BETWEEN DYNCORP INTERNATIONAL LLC (5-RC-15850 & 5-RC-074500) AND INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF MACHINISTS AND AEROSPACE WORKERS, AFL-CIO, DISTRICT LODGE 4, LOCAL LODGE 24 AT JOINT BASE ANDREWS, MD EFFECTIVE SEPTEMBER 1, 2020 through AUGUST 31, 2023 Table of Contents PURPOSE OF AGREEMENT .................................................................................................................. 4 ARTICLE 1 GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT ................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1- GENERAL PROVISIONS ............................................................................................................................................ 4 SECTION 2 - RECOGNITION AND EXCLUSIVE REPRESENTATION ............................................................................................... 5 SECTION 3 - PERIOD OF AGREEMENT AND RATIFICATION ........................................................................................................ 7 SECTION 4 - SUCCESSORS AND ASSIGNS ................................................................................................................................... 7 SECTION 5 - SEPARABILITY ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 SECTION 6 - STRIKES AND LOCKOUTS .......................................................................................................................................