Part 2 (Autumn 2004)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 100 the Derwent Valley 100 95 95

DERWENT VALLEY MILLS DERWENT VALLEY 100 The Derwent Valley 100 95 95 75 The Valley that changed the World 75 25 DERWENT VALLEY MILLS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 25 5 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 5 0 0 Edited by David Knight Inscriptions on UNESCO's SITE RESEARCH FRAMEWORK WORLD HERITAGE prestigious World Heritage List are based on detailed research into the sites' evolution and histories. The role of research does not end with the presentation of the nomination or indeed the inscription itself, which is rst and foremost a starting point. UNESCO believes that continuing research is also central to the preservation and interpretation of all such sites. I therefore wholeheartedly welcome the publication of this document, which will act as a springboard for future investigation. Dr Mechtild Rössler, Director of the UNESCO Division for Heritage and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre 100 100 95 95 75 75 ONIO MU IM N R D T IA A L P W L O A I 25 R 25 D L D N H O E M R E I T I N A O GE IM 5 PATR 5 United Nations Derwent Valley Mills Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World 0 Cultural Organisation Heritage List in 2001 0 Designed and produced by Derbyshire County Council, County Hall, Matlock Derbyshire DE4 3AG Research Framework cover spread print 17 August 2016 14:18:36 100 100 95 95 DERWENT VALLEY MILLS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 75 75 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 25 25 5 Edited by David Knight 5 0 0 Watercolour of Cromford, looking upstream from the bridge across the River Derwent, painted by William Day in 1789. -

Catalogue of the Box “Derbyshire 01”

Catalogue of the Box “Derbyshire 01” Variety of Item Serial No. Description Photocopy 14 Notes by Mr. Wright of Gild Low Cottage, Great Longstone, regarding Gild Low Shafts Paper Minutes of Preservation Meeting (PDMHS) 10-Nov-1985 Document and Plan List of Shafts to be capped and associated plan from the Shaft Capping Project on Bonsall Moor Photocopy Documents re Extraction of Minerals at Leys Lane, Bonsall, 21-Oct-1987 – Peak District National Park Letter From the Department of the Environment to L. Willies regarding conservation work at Stone Edge Smelt Chimney, 30-Mar-1979 Typewritten Notes D86 B166 Notes on the Dovegang and Cromford Sough (and other places) with Sketch Map (Cromford Market Place to Gang Vein) – Maurice Woodward Transcription S19/1 B67 “A Note on the Peculiar Occurrence of Lead Ore in the Ewden Valley, Yorkshire” by M.E. Smith from “Journal of the University of Sheffield Geological Society” 1958/9 S19/2 B11 “The Lead Industry of the Ewden Valley, Yorkshire” by M.E. Smith from “The Sorby Record” Autumn 1958 S22 B120 “The Odin Mine, Castleton” by M.E. Smith from “The Sorby Record” Winter 1959 All Items in One Envelope (2 Copies) Offprint “Discussion on the Relationship between Bitumens and Mineralisation in the South Pennine Orefield, Central England” by D.G. Quirk from “The Journal of the Geological Society of London” Vol. 153 pp653-656 (1996) Report B201 Geological Report on the Ashover Fluorspar Workings by K.C. Dunham to the Clay Cross Company 15-May-1954 Folder B24 Preliminary Notes on the Fauna and Palaeoecology of the Goniatite Bed at Cow Low Nick, Castleton by J.R.L. -

A Brief History by WILL SWALES Welcome

a brief history BY WILL SWALES welcome Welcome to a brief history of The Rutland Arms Hotel, Bakewell. During the late spring and early summer of 2016 we had the good fortune to be able to revitalise and refurbish one of our fabulous sister inns, The King’s Head in Richmond, North Yorkshire. During the planning stage of this project we started to look hard at the building and its many historical attributes, at how some parts of the building had been added during its 300 years of existence. And whilst contemplating the small changes and additions we wanted to make, it dawned on me that we will only be its custodians for a generation or two at most. I can’t foretell who will follow but started thinking about who had been its keepers in the past. Therefore, we asked a good friend if he would research The King’s Head and try to separate the fact from the fable; what’s true and what has been elaborated during the storytelling process over the years. Will Swales made such a good job of The King’s Head that we then asked him to complete the same task for The Rutland Arms Hotel. What follows is that research. We think it’s as accurate as can be, but naturally there are many gaps and we would welcome any additional information. I hope you enjoy this small booklet and the hospitality and service we provide within The Rutland Arms Hotel. Please feel free to take this copy with you. Kevin Charity Managing Director The Coaching Inn Group www.coachinginngroup.co.uk Copyright © 2020 The Coaching Inn Group Ltd., Boston, Lincolnshire, PE21 6BZ Designed by www.penny-wilson.co.uk “derbyshire’s most famous inn” 3 The recently refurbished dining room at The Rutland Arms Hotel. -

The Growth of Geological Knowledge in the Peak District Trevor D

The Growth of Geological Knowledge in the Peak District Trevor D. Ford Abstract: The development of geological knowledge in the Peak District from the 18th century to the present day is reviewed. It is accompanied by a comprehensive bibliography. Introduction lead miners made practical use of geological principles as early as the 17th century (Rieuwerts, Geology has changed in the last two centuries from 1984). In the 18th century the course of the initial a largely amateur “gentleman’s” science to a part of Cromford Sough followed the strike of the professional vocation. The results of professional limestone/shale contact where excavation was easier investigation in the Peak District have been built on through shale. The position of the contact was the amateur foundation and the works cited in this obtained by down-dip projection from the outcrop review demonstrate the change in approach. The showing that the soughers had some appreciation of Geological Survey commenced a professional concealed geology. The lead miners also used the approach in the 1860-1880 period, continued basic principles of stratigraphy and structure to during World War I and in the 1950s, but it was not predict whether or not they would intersect until the 1970s that some intensive economic toadstones in driving other soughs in the 18th investigations were pursued. The Geological century (Fig. 1). Survey’s activities in the 20th century were concurrent with the development of Geology Whilst most of the lead miners’ knowledge was Departments in the nearby Universities, where never written down, some of it has been preserved in research grew slowly after World War I and more the appendix to “An Inquiry into The Original State rapidly after World War II. -

(As a Potential Geopark): Mining Geoheritage and Historical Geotourism

Acta Geoturistica, vol. 8 (2017), nr. 2, 32-49 DOI 10.1515/agta-2017-0004 The English Peak District (as a potential geopark): mining geoheritage and historical geotourism THOMAS A. HOSE School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Building, Queens Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK ABSTRACT The Peak District is an upland region in central Britain with a rich mining geoheritage. It was established as the UK’s first National Park in 1951. It was the region, due to its widespread loss quarries and mines sites to inappropriate remedial measures, which led to the recognition and promotion of the modern geotourism paradigm. It is the birthplace of British geotourism with the earliest recorded instances of leisure travellers purposefully choosing to visit mines and caves. Metalliferous mining in the region can be traced back to the Bronze Age. Gangue minerals, especially fluorspar and barites, later became significant primary extraction activities and underpinned a small-scale semi-precious stone industry. It is home to the World Heritage inscribed site of the Derwent Mills, significant in the development of early Industrial Revolution textile technology and manufacturing practices. The almost equally significant mining geoheritage has yet to be similarly recognised and, indeed, its survival is still threatened because most tourism and many mining geoheritage stakeholders have a limited understanding of geo-history and the geo-interpretive significance of the individuals and geosites that shaped historical geotourism and geological exploration in the Peak District; their exploits and the legacy of their publications, alongside its superbly exposed and well researched geology and associated mining geoheritage, could underpin a bid for the region’s recognition as a geopark. -

ITEM 11 1 December 2015

Classification: OFFICIAL REGENERATING OUR CITY OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY BOARD ITEM 11 1 December 2015 Report of the Acting Strategic Director of Communities and Place Derby Museums Trust – Annual Report Summary SUMMARY 1.1 The Regenerating Our City Scrutiny Board has requested an update from Derby Museums. This report provides a summary of the key achievements over the last year and the key next steps planned for the continued development of Derby Museums. The Annual Report is provided in Appendix 2. 1.2 The success of the bid to the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) for £9.38m to redevelop Derby Silk Mill and the next stages of activity for the project are highlighted in the report. The total cost of the project is £16.4m and the successful bid from the HLF is the largest ever awarded to the city. RECOMMENDATION 2.1 To note the significant progress and results that have been achieved by Derby Museums in its first three years of operation as well as the mitigation the organisation will need to take in the context of reduced funding from the Council. 2.2 To note the outstanding success of the Silk Mill bid, the details of the programme for the project and the need to secure match funding from a range of sources. REASONS FOR RECOMMENDATION 3.1 To ensure that the Board is aware of the significant progress being made and the impact to both the public and the organisation of the proposed cuts to the budget. 3.2 To ensure that the Board is aware of the importance of the Silk Mill development to the city as a major heritage attraction. -

Marble Mill in Henry Watson's Time

Bulletin ofthe Peak District Mines Historical Society. Volume 12, Number 6. Winter 1995. THE ASHFORD MARBLE WORKS AND CAVENDISH PATRONAGE, 1748-1905 Trevor Brighton Abstract: The marble industry in Ashford in the late 18th and 19th centuries struggled to compete with its rivals in other Derbyshire towns. At first the Ashford mill had distinct advantages in terms of its adjacent marble quarries, its water power and the ingenious machine patented by Henry Watson of Bakewell. The mill also enjoyed the patronage of the Dukes of Devonshire, Lords of Ashford. However, after the 6th Duke's completion of the sumptuous north wing at Chatsworth and his subsequent death the patronage declined and so did the industry. By the beginning of this century it had virtually vanished in the county. For a century and a half the small marble working industry at turning vases from local spars. Ashford-in-the-Water owed its existence and prosperity principally to members of the Cavendish family at Chatsworth. In the year 1743 as Lord Duncannon, and Henry Watson of They continually encouraged a succession of ingenious Bakewell, statuary, were riding in Eyam Dale, his Lordship's proprietors, to whom they leased the marble quarries, in or near horse stumbled on a piece of water-icicle (stalagmite) which lay Ashford, together with mill sites on the River Wye. Thus a small in the road, which appearing a different nature of stone from what Peakland craft whose products of black and grey marble can be they had generally seen on the road, his Lordship asked Mr traced back to prehistoric times became an industry of some Watson ifhe thought it possible to produce a quantity ofit and to national importance in the 19th century. -

WHITE WATSON by George Challenger

WHITE WATSON by George Challenger White Watson (1760-1835) was Bakewell’s most famous inhabitant. He was nationally important as one of a group of geologists including J Mawe, J Whitehurst , William Martin, John Farey and William Smith - the ‘Father of English Geology’- who established the fundamental law of stratigraphy, the branch of geology which deals with the nature and order in which rocks were laid down. Indeed, a 1973 exhibition on the subject in Derby Museum by M F Stanley put ‘the heroic age of geology’ as starting in 1773 when Watson probably began collecting fossils. Watson wrote his book ‘A Delineation of the Strata of Derbyshire’ in 1811, which described in detail the various rocks and the fossils in them. He was unique in producing geological cross sections using many of the actual rocks. One of these sections is displayed in Bakewell’s Old House Museum . It follows the section described in his book from Coombs Moss beyond Buxton to Bolsover beyond Chesterfield and going through Bakewell. Several other of his sections are in Derby Museum. Trevor Brighton describes White Watson as a polymath: Like his uncle and grandfather before him he was a monumental mason and carver, but was also an antiquarian, museologist, silhouette artist, writer, gardener and plantsman. His botanical and horticultural pursuits earned him election as a fellow of the Linnaean Society. At the Duke of Rutland’s Bath House, where he lived in Bakewell, he not only revitalised the town’s bathing facilities, but laid out the grounds to establish a botanical garden. Within his house he had created, by his death in 1835, a museum of geology, natural history and archaeology. -

Part 07 (Oct 1957)

DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY The Bulletin of The Local History Section of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Number 7 October 1957 DERBYSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL & NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY Local History Section Chairman Mr.J.M.Bestall, M.A., Treasurer 6 Storth Avenue, Mrs.P.Nixon, B.A., SHEFFIELD 10 Mr, W.D.White, "Southlea", "Normanhurst", Hazlewood Road, Tel: Sheffield 33016 175 Derby Road, Duffield, Chellaston, DERBYSHIRE. DERBY. Tel: Duffield 2325 COMVUTTEE Tel: Chellaston 3275 Mr.Owen Ashmore, M.A, Mr.J.Marchant Brooks Mr.C.Daniel Mr.Francis Fisher Mr.C .C.Handford Mr.C,H.Hargreaves M r . G. R. Mi ckl ewright In Charge of Records:- Mr.A.E.Hale, Mr.A.H.Hockey, Mr.H.Trasler THE ANNUAL GENERAL This will be held in the Derby Borough Technical College, Normanton Road, at 2.30 pm. on Saturday, November 30th. The first part of the meeting will be taken up with shoi’t talks by members on their work. Miss A.B.Smedley will show colour slides of local historical interest. Mr,W.D.White will tell us briefly how he has gathered information for his monograph on Ydiitehurst. Mr.Francis Fisher will give some details of the material he has come across while calendaring family papers. Offers of talks of about ten minutes duration will be welcomed by the Section Secretary and should be sent in as soon as possible. It is hoped that there will be a vigorous discussion and exchange of experiences. The Annual General Meeting will follow the tea-break. - 83 - Number 7 DERBYSHIRE MISCELLANY October 1957 SECTION NEWS Publication of this Autumn Bulletin has been delayed by a number of causes, chief of which has been the time required to type Supplement 2, '’A Village Constable’s Accounts"„ It is hoped that when members see this Supplement they will feel that the delay has been justified. -

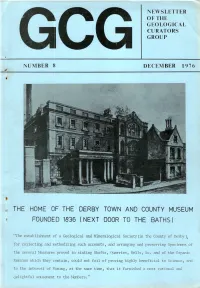

Founded 1836 (Next Door to the Baths)

NEWSLETTER OETHE GEOLOGICAL CURATORS GROUP NUMBER 8 DECEMBER 1976 % I 1 si THE HOME OF THE DERBY TOWN AND COUNTY MUSEUM FOUNDED 1836 (NEXT DOOR TO THE BATHS) "The establishment of a Geological and Mineralogical Society [in the County of Derby for collecting and methodizing such accounts, and arranging and preserving Specimens of the several Measures proved in sinking Shafts, Quarries, Wells, &c. and of the Organic , Remains which they contain, could not fail of proving highly beneficial to Science, and to the interest of Mining, at the same time, that it furnished a most rational and delightful amusement to the Members." \ CO\/ER The quotation on the cover is from 'A General View of the Agriculture and Minerals of Derbyshire' vol., I, LONDON 1811 ; John FAREY'S early plea for the establishment of a Derbyshire Geological Museum. For the tragic story see inside. Back numbers of Newsletters are still available at £1 each (including postage). Remuneration must accompany all orders, which should be sent to Tim Riley, Sheffield City Museum.s, Weston Park, Sheffield SIO 2TP. Submission of MSB Three Newsletters are published annually. The last dates for submission of MSB for publication are: March 1st for April issue August 1st for September issue November 1st for December issue. iMSB should be sent to the editor typed and double-spaced, please. .ADi^RTIBBevr CHARGES Full A4 page £20 per issue Half A4 page £10.50 per issue Further details from the Editor. © Published by the Geological Curators Group. Printed at Keele University. For further details please contact either the Editor or the Secretary. -

White Watson (1760-1835)

WHITE WATSON (1760-1835) G P. Challenger In his introduction to the reprint of Watson's "The Strata of Derbyshire" Ford (1973) discusses the importance of Watson as a geologist and gives sketches of his character and family history. He also lists Watson's publications and manuscripts, chiefly on geological subjects. This article is mainly about non-geological aspects of his life and his observations on the neighbourhood of Bakewell. He left Sheffield School to help his uncle Henry at the Ashford Marble works. When that was sold after Henry's death in 1786, he carried on a variety of activities at the Bath House, Bakewell, (now Haig House) where he lived until his death. Besides his geological studies and lectures, he collected and sold fossils and minerals; designed and executed monuments, fireplaces etc; laid out Bath Gardens (since altered); studied plants; wrote poems; "dissected" the Bible; drew profiles of visitors and kept a museum and reading room. His wife was proprietress of the warm bath after it was restored in 1817. BAKEWELL, DERBYSHIRE. ] WHITE W A T S O N, ( ( NCJ.IXU mdSuculbf m Mr. HtNRY WATSON, lucof BiktwU. ) | i ' ' • R K G S leave to acquaint the Nobility, Gentry and others, that he exo- j ' *~^ cutes Moiiumenu, Chimney 1'ieces, Table*, V«les and other Ornaments, ! | in all the variety of Engiilh and Vorc^n NUiblts, agreeable to die modem I • Tallc »uJ upon the moll rcaiuiublc Terms. J W. WATSON, having aticmive!/ collected the Minerals and FoffiUof 1 ' Dtriyjhin, is now in pullelhon ol' a valu.bU AfToumcnt ready for the iu- ! fpcctiun of i!ie Curious, and uiulouk.cs to execute orders for the like ! ; I'jodutlioiis, properly anangcd LinJ ^U-iLiilicd, «• A collector and SC!!LT oi'all t h i s son of work, and curiosity; but which is to hcaeen to more pcrtcc.iioii in many shopd in London. -

Some Castleton History Some Castleton History and Things Remembered by Peter C

Some Castleton History Some Castleton History and Things Remembered By Peter C. Harrison. It is quite true to say that over the years many millions of people have visited Castleton. For instance, in 1975 the Peak District National Park Authority carried out a traffic and visitor survey, their findings were amazing! 25 million people visited the National Park and of that 25 million, 8 million came to Castleton. Nearly all the visitors to Castleton will look around the many gift shops, visit a pub or café, look up at Peveril Castle perched high above the village; some of them even climb up to it and from there the views around the Hope Valley are spectacular. Only a minority of all these visitors will realise what an interesting and wonderful place Castleton is and what a wealth of history is all around them. No one seems to know for sure how long ago it was when the first settlement appeared where Castleton is today, but it must be a very long time ago. I hope what follows will give you an insight into Castleton history and into village life as well. Early History No evidence has been found of human cave dwellers locally, even inside Peak Cavern, although cave dwelling continued up to about 2000 years ago. There is evidence of Neolithic people living locally at least 3500 BC (5500 years ago) in the form of a Neolithic family burial in a natural cave on Treak Cliff. Celtic people were living on Mam Tor about 1000 BC (3000 years ago), they were Brigantes from Northumbria who settled on Mam Tor about 1000 BC.