A Brief History by WILL SWALES Welcome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haddon Hall's Poems

HADDON HALL’S POEMS NINETEENTH CENTURY SENTIMENTS DAVID TRUTT Copyright © David Trutt 2007 All rights reserved. Haddon Hall’s Dorothy Vernon - The Story Of The Legend was published in 2006. The following people were very helpful during the formation of this book: Sandra Trutt provided much needed help and support. Kendra Spear digitized various engravings. Alastair Scrivener pointed out the use of the Haddon Hall illustration for the poem In The Olden Time. His Buxton bookshop has been the source of many hard-to-find books on Derbyshire and its environs. Revised October 2010: Pages 4, 6, 124 to reflect that the author of “A Legend of Haddon Hall” was John James Robert Manners 7th Duke of Rutland, and not as indicated, John Henry Manners 5th Duke of Rutland, his father. Both were alive in 1850 when English Ballads and Other Poems was published. Published by David Trutt Los Angeles, California USA [email protected] CONTENTS 3 Contents 3 Introduction 7 The Seven Foresters Of Chatsworth (1822) Allan Cunningham 11 The King Of The Peak, A Derbyshire Tale (1822) Allan Cunningham 21 The King Of The Peak, A Romance (1823) William Bennet 25 Haddon Hall, A Poetical Sketch (1823) John Holland 27 Haddon Hall, Bijou (1828) H. B. (Mary Hudson Balmanno) 37 Haddon Hall At The Present Day (1841) Benjamin Fenton 40 Haddon Hall Before 1840 Henry Alford (1836) 49 Henry Glassford Bell (1832) 50 Delta (David Moir) (1834) 52 George Bayldon (1838) 54 F. R. C. (1831) 55 Haddon, Reliquary (1863) Llewellynn Jewitt 56 The Elopement Door (1869) William Kingston Sawyer 57 Visiting Chatsworth and Haddon Hall (1860) E. -

Peak Shopping Village Rowsley, Nr Matlock, Derbyshire, De4 2Je

PEAK SHOPPING VILLAGE ROWSLEY, NR MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE, DE4 2JE UNIT 28A – LEISURE UNIT – APPROX 5,000SQFT LOCATION RENT Peak Village is located on the A6 equidistant to Matlock On request. and Bakewell within the Village of Rowsley. SERVICE CHARGE DESCRIPTION There is a service charge payable on all the properties The Centre benefits from close proximity to Chatsworth which includes full maintenance and cleaning of the House and is already home to various multiple retailers premises, site security and an annual marketing including Edinburgh Woollen Mill, Massarellas, programme including a full Events Programme. Cotton Traders, Mountain Warehouse, Regatta, The Works, Pavers, Holland & Barratt and Leading Labels RATES as well as other local independents. Interested parties should verify these figures with Derbyshire Dales District Council Business Rates In addition we have recently let part of the Scheme to Department (Tel:01629 761100). Bamfords Auction House who regularly feature on BBC television. LEGAL COSTS Each party to bear their own legal costs incurred in this The Centre comprises over 60,000sqft and there are transaction. over 450 free car parking spaces. VIEWING ACCOMMODATION All enquires or arrangements to view should be via the Unit 28a can be extended to circa 5,000sqft. This sole agents, Dresler Smith. incorporates a tower giving a huge height perfect for various leisure activities. Dresler Smith (Tel: 0113 245 5599) Contact: Richard Taylor LEASE [email protected] Available by way of internally repairing and insuring leases on flexible terms with incentives for the right SUBJECT TO CONTRACT uses. Date of particulars: June 2016 EPC’s to Follow Additional detailed Plans on request www.dreslersmith.co.uk T: 0113 245 5599 Kenneth Hodgson House, 18 Park Row LS1 5JA Doncaster Manchester Oldham Rotherham 4 HRS FREE PARKING Stockport Welcome to Peak Shopping Village Chatsworth in the heart of the stunning Peak District.. -

Privilege of the Entree, Which Are to Proceed Down The'park, and Enter

1026 privilege of the entree, which are to proceed down Prelate standing on the right haad- of the So- the'Park, and enter the Palace at Stable-yard-gate, vereign, the Registrar, Deputy Garter, and Black Rod at the bottom of the table. turn into the Ambassadors'-court, set down at the The Prelate then signified to the Chapter, Arcade, and go cut into Cleveland-row. The car- the Sovereign's 'royal will and pleasure, that the riages of the Cabinet Ministers and'Great Officers vacant stall in the Royal Chapel of St. George at of State may afterwards wait in the King's-court Windspr be filled; and, as by the statutes none but a Knight can be elected, his Grace Edward-Adol- those of the Ambassadors and Foreign Ministers in phus Duke of Somerset, was introduced by Deputy the Anibassadors'-court> and those of all other per- Garter and Black Rod, and knighted by His Ma- sons having the entree may wart in Stable-yard or jesty with the, sword of state, and his Grace, having kissed the Sovereign's hand, retired. St. James's-park till called for} they are then to The Knights Companions then "proceeded tp the ; take up .in. the same order as they had set down, election, and the suffrages having been collected by , pass away into Cleveland-row, and up the left hand the Prelate, were by him presented to the Sove- side of St. James's-street, reign, who was pleased to command him to declare, and he accordingly declared, that the Most Noble No carriage will be admitted with company a Edward-Adolphus Duke of Somerset had been elected a Knight of the Most Noble Order of the s^e.ond time with the same ticket, to prevent which, Garter. -

My Rössl AUTUMN/WINTER 2020-2021 AUTUMN/WINTER LEGENDARY

english My Rössl AUTUMN/WINTER 2020-2021 LEGENDARY. Legendary: Peter Alexander as head waiter Leopold in the cult comedy ‘The White Horse Inn.’ Congenial: Waltraut Haas as resolute and smart Rössl hostess Josepha Vogelhuber. Overwhelmingly beautiful: Lake Wolfgangsee with all its possibilities for recreation, relaxation and exercise. Majestic: The mountains with unforgettable views down to the lakes. A gift from heaven: The fresh and heal- thy air – breathe deeply again and again. Typically Austrian: The warm hospitality, the culinary delights, the relaxed cosiness, the gentle Alpine pastures, the great hi- king and winter experiences. In a word: Legendary. Experience the good life at the Weisses Rössl at Lake Wolfgangsee. 1 FOR MY RÖSSL GUESTS Dearest Rössl guests, there was already so much that I had wanted to tell you when we started “My Rössl” one year ago. I have so much to share about festivals at the Rössl and the year of legends at the Lake Wolfgangsee. Then a little virus came along that changed the whole world. What you now hold in your hands is our lifeblood. After all, on some days all we have left is our belief that the legendary Weisses Rössl, which has existed for over 500 years, will continue to do so for a long time to come. Our confidence is thanks to you and all of our guests. I would be remiss in not expressing my gratitude at this stage for your loyalty. Thank you to all of you who have been with us at Lake Wolf- gangsee these past weeks and finally gave us the opportunity to bring joy to people. -

New Mills Library: Local History Material (Non-Book) for Reference

NEW MILLS LIBRARY: LOCAL HISTORY MATERIAL (NON-BOOK) FOR REFERENCE. Microfilm All the microfilm is held in New Mills Library, where readers are available. It is advisable to book a reader in advance to ensure one is available. • Newspapers • "Glossop Record", 1859-1871 • "Ashton Reporter"/"High Peak Reporter", 1887-1996 • “Buxton Advertiser", 1999-June 2000 • "Chapel-en-le-Frith, Whaley Bridge, New Mills and Hayfield Advertiser" , June 1877-Sept.1881 • “High Peak Advertiser”, Oct. 1881 - Jul., 1937 • Ordnance Survey Maps, Derbyshire 1880, Derbyshire 1898 • Tithe Commission Apportionment - Beard, Ollersett, Whitle, Thornsett (+map) 1841 • Plans in connection with Railway Bills • Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway 1857 • Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway 1857 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1860 • Marple, New Mills and Hayfield Junction Railway 1860 • Disley and Hayfield Railway 1861 • Midland Railway (Rowsley to Buxton) 1862 • Midland Railway (New Mills widening) 1891 • Midland Railway (Chinley and New Mills widening) 1900 • Midland Railway (New Mills and Heaton Mersey Railway) 1897 • Census Microfilm 1841-1901 (Various local area) • 1992 Edition of the I.G.I. (England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Isle of Man, Channel Islands • Church and Chapel Records • New Mills Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1794-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Baptisms 1830-1837 • New Mills Independent Chapel, Burials 1832-1837 • Glossop Wesleyan Chapel, Baptisms 1813-1837 • Hayfield Chapelry and Parish Church Registers • Bethal Chapel, Hayfield, Baptisms 1903-1955 • Brookbottom Methodist Church 1874-1931 • Low Leighton Quaker Meeting House, New Mills • St.Georges Parish Church, New Mills • Index of Burials • Baptisms Jan.1888-Sept.1925 • Burials 1895-1949 • Marriages 1837-1947 • Coal Mining Account Book / New Mills and Bugsworth District 1711-1757 • Derbyshire Directories, 1808 - 1977 (New Mills entries are also available separately). -

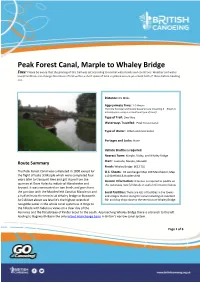

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please Be Aware That the Grading of This Trail Was Set According to Normal Water Levels and Conditions

Peak Forest Canal, Marple to Whaley Bridge Easy: Please be aware that the grading of this trail was set according to normal water levels and conditions. Weather and water level/conditions can change the nature of trail within a short space of time so please ensure you check both of these before heading out. Distance: 6½ Miles. Approximate Time: 1-3 Hours The time has been estimated based on you travelling 3 – 5mph (a leisurely pace using a recreational type of boat). Type of Trail: One Way Waterways Travelled: Peak Forest Canal Type of Water: Urban and rural canal. Portages and Locks: None Vehicle Shuttle is required Nearest Town: Marple, Disley, and Whaley Bridge Route Summary Start: Lockside, Marple, SK6 6BN Finish: Whaley Bridge SK23 7LS The Peak Forest Canal was completed in 1800 except for O.S. Sheets: OS Landranger Map 109 Manchester, Map the flight of locks at Marple which were completed four 110 Sheffield & Huddersfield. years later to transport lime and grit stone from the Licence Information: A licence is required to paddle on quarries at Dove Holes to industrial Manchester and this waterway. See full details in useful information below. beyond. It was constructed on two levels and goes from the junction with the Macclesfield Canal at Marple six and Local Facilities: There are lots of facilities in the towns a-half-miles to the termini at Whaley Bridge or Buxworth. and villages that lie along the canal including an excellent At 518 feet above sea level it’s the highest stretch of fish and chip shop close to the terminus at Whaley Bridge. -

Malaysia Halal Directory 2020/2021

MHD 20-21 BC.pdf 9/23/20 5:50:37 PM www.msiahalaldirectory.com MALAYSIA HALALDIRECTORY 2020/2021 A publication of In collaboration with @HDCmalaysia www.hdcglobal.com HDC (IFC upgrade).indd 1 9/25/20 1:12:11 PM Contents p1.pdf 1 9/17/20 1:46 PM MALAYSIA HALAL DIRECTORY 2020/2021 Contents 2 Message 7 Editorial 13 Advertorial BUSINESS INFORMATION REGIONAL OFFICES Malaysia: Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd (3024D) Useful Addresses Business Information Division 27 Bangunan Times Publishing Lot 46 Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park Batu Tiga 40000 Shah Alam 35 Alphabetical Section Selangor Darul Ehsan Malaysia Tel: (603) 5628 6886 Fax: (603) 5636 9688 Advertisers’ Index Email: [email protected] 151 Website: www.timesdirectories.com Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Business Information Private Limited 1 New Industrial Road Times Centre Singapore 536196 Tel: (65) 6213 9300 Fax: (65) 6285 0161 Email: [email protected] Hong Kong: Marshall Cavendish Business Information (HK) Limited 10/F Block C Seaview Estate 2-8 Watson Road North Point Hong Kong Tel: (852) 3965 7800 Fax: (852) 2979 4528 Email: [email protected] MALAYSIA HALAL DIRECTORY 2020/2021 (KDN. PP 19547/02/2020 (035177) ISSN: 2716-5868 is published by Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Business Information - 3024D and printed by Times Offset (M) Sdn Bhd, Thailand: Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Green World Publication Company Limited Tel: 603-5628 6888 Fax: 603-5628 6899 244 Soi Ladprao 107 Copyright© 2020 by Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Business Information – 3024D. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley

High Peak and Hope Valley January – April 2020 Community Rail Partnership Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley Welcome to this guide It contains details of Guided Walks and Folk Trains on the Hope Valley, Buxton and Glossop railway lines. These railway lines give easy access to the beautiful Peak District. Whether you fancy a great escape to the hills, or a night of musical entertainment, let the train take the strain so you can concentrate on enjoying yourself. High Peak and Hope Valley This leaflet is produced by the High Peak and Hope Valley Community Rail Partnership. Community Rail Partnership Telephone: 01629 538093 Email: [email protected] Telephone bookings for guided walks: 07590 839421 Line Information The Hope Valley Line The Buxton Line The Glossop Line Station to Station Guided Walks These Station to Station Guided Walks are organised by a non-profit group called Transpeak Walks. Everyone is welcome to join these walks. Please check out which walks are most suitable for you. Under 16s must be accompanied by an adult. It is essential to have strong footwear, appropriate clothing, and a packed lunch. Dogs on a short leash are allowed at the discretion of the walk leader. Please book your place well in advance. All walks are subject to change. Please check nearer the date. For each Saturday walk, bookings must be made by 12:00 midday on the Friday before. For more information or to book, please call 07590 839421 or book online at: www.transpeakwalks.co.uk/p/book.html Grades of walk There are three grades of walk to suit different levels of fitness: Easy Walks Are designed for families and the occasional countryside walker. -

•Œthe Popular Repertory and the German-American Audience: The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of of Theatre and Film 2001 “The opulP ar Repertory and the German- American Audience: the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee, 1885-1909” William Grange University of Nebraska, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Grange, William, "“The opulP ar Repertory and the German-American Audience: the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee, 1885-1909”" (2001). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film. 17. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/theatrefacpub/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Theatre and Film, Johnny Carson School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Theatre and Film by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. German-Language Theatre in Milwaukee, 1885-1909 William Grange University of Nebraska Lincoln, NE 68588-0201 The history of German-language theatre in Milwaukee is bound together with the history of German-speaking settlers in Wisconsin and with the theatre culture of Germany as it unfolded after the 1848 revolution. The two histories at first glance seem to have nothing to do with one another; upon closer analysis, however, one discovers a fascinating association between the two— in fact, there are even instances of the two influencing each other. -

Temptations CATALOG 2018/19 Italian Desserts THAT STARTED with a BICYCLE in 1946 a Passion for Pastry IS OUR FAMILY LEGACY

Sweet Temptations CATALOG 2018/19 Italian desserts THAT STARTED WITH A BICYCLE IN 1946 A passion for pastry IS OUR FAMILY LEGACY 1946 1959 1972 BEYOND THE A NEW LARGER THE STORY BEGINS CITY OF MILAN FACILITY Our story begins with a bicycle in In time, Bindi was able to The Bindi operation moved from 1946, in the city of Milan, Italy. satisfy those who demanded a small workshop to a large plant Attilio Bindi, Tuscan restaurateur and craved his creations allowing for increased production and founder of the company, throughout the rest of Italy. and for the first time – cold chain driven by his passion for sweets, distribution. The new facility allows opened his original “Pasticceria” for the product range to broaden on Via Larga. and the first Bindi tiramisu is produced. The Bindi logo and tag line debuts. “Fantasia nel Dessert,” which translates to “Creativity in Dessert,” represents the company’s expanded horizons. 1990 2001 2018 BINDI LANDS PRODUCTION THE HISTORY IN THE USA IN THE USA CONTINUES Bindi began importing Bindi opens its first Today, over half a century later, the and distributing its line of production plant in the USA. Bindi family still runs the business. products in the USA. The 56,000 sq. ft. plant is Bindi is known and appreciated located in Belleville, NJ. worldwide for its wide array of high quality desserts. Attilio Bindi, Romano’s son, is guiding the subsidiary in the US, spreading the family heritage, the passion for pastries and guaranteeing the very same consistency that makes a Bindi dessert unique everywhere. -

Bakewell.Indd - Guide Peak 230657 09:44 21/02/2019

1-5 Bakewell.indd - Guide Peak 230657 09:44 21/02/2019 Centres Visitor and Refreshments Shops: Rowsley Baslow, Longstone, Great Bakewell, Hire, Cycle Includes Youlgreave Peak, in Stanton Shops: Bakewell Map Scale 1:50,000 Pubs: Rowsley, Beeley, Baslow, Hassop, Longstone, Great 7 Pubs: river) the by trail, (below Dale Millers Bakewell, 8 Cafes: Rowsley Beeley, Chatsworth, Edensor, Baslow, Station, Hassop 6 (seasonal) Mill Blackwell and trail road/3% 97% Cafes: Dale, Millers year), (all Station Hassop Grade: Hard trail 100% Ascent: 674m/2211ft Grade: Easy 5 Distance: 29km/18miles Ascent: 148m/487ft 1NW DE45 Trail) Monsal (on Distance: 29km/18miles Point: Start/End park car Hire Cycle and Café Station Hassop 1NW DE45 Trail) Monsal (on park car start. the to return Point: Start/End Hire Cycle and Café Station Hassop to Hassop signposted L second Take SA. Wye River the Cross 10. way. same the back trail the follow and around Turn 2. centre. town the through care taking 1 Mill. Blackwell at end the to trail the on continue and roundabout, at exit 2nd take immediately and way) (one A6 the Trail Monsal the along TR carpark Station Hassop From 1. onto TL Bakewell. into downhill TR T-jct next at and Continue 9. route traffic-free stunning A uphill. steeply continue and crossing river Conksbury to downhill TR T-jct next At Haddon) Trail Monsal The Over (signpost church the opposite PH George the at TR 8. 2 ROUTE 9 Youlgreave. towards road main the along L turn then L, to i road follow Alport, into bridge small a over downhill go T-jct, at TR then Hall), Harthill for (signs TL 50m about After TR.