Some Castleton History Some Castleton History and Things Remembered by Peter C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009 Catherine Collins 2 Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire in 2008 and 2009 By Catherine Collins 2017 Access Cambridge Archaeology Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Cambridge Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QG 01223 761519 [email protected] http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/ (Front cover images: view south up Castle Street towards Peveril Castle, 2008 students on a trek up Mam Tor and test pit excavations at CAS/08/2 – copyright ACA & Mike Murray) 3 4 Contents 1 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 ACCESS CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2 THE HIGHER EDUCATION FIELD ACADEMY ............................................................................................ 8 2.3 TEST PIT EXCAVATION AND RURAL SETTLEMENT STUDIES ...................................................................... 9 3 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND DESIRED OUTCOMES ........................................................................ 10 3.1 AIMS .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Visitor Economy Plan 2015-2019.Pdf

1 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Value of the Visitor Economy 3 3. Visitor Perceptions and Behaviours 5 4. Strategic Fit 6 5. Current Offer and Opportunities for Growth 8 6. Growing the Value of the Visitor Economy 9 7. Priorities and Actions 12 8. Measures of Success 14 2 1. Introduction A strong visitor economy is important to the economic health of the Derbyshire Dales. Generating an estimated £315m in visitor spend it provides employment, offers business opportunities and helps sustain local services – but there is room for growth. To grow the value of the sector visitors need to be encouraged to spend more when they come. Promoting the special qualities of the Dales, improving the visitor ‘welcome’, providing better experiences and working towards a higher value visitor offer will help achieve this. This plan takes its lead from the District Council’s Economic Plan. Drawing on the area’s distinctive rural offer, proximity to urban markets and already high visitor numbers (relative to other Derbyshire districts), the aim of the plan is: AIM: To develop a higher value visitor economy in the Derbyshire Dales Doing everything needed to achieve this aim is a ‘big ask’ of the District Council and is not the purpose of this plan. Rather, within the context of available resources, effort will be focused on three priorities where District Council intervention can make a difference, complementing and adding to the activities of our partners and other stakeholders: PRIORITIES: 1. Support businesses within the visitor economy to exploit key markets and supply chain opportunities 2. -

Derwent Valley Line

Prices correct at November 2018 November at correct Prices (Newark) – Nottingham – Derby – Matlock – Derby – Nottingham – (Newark) derbyshire.gov.uk/bline long as one end of your journey is in Derbyshire. in is journey your of end one as long © Matt Jones Matt © . Receive 25% off local train fares as as fares train local off 25% Receive 01629 533190 01629 Derbyshire Call Derbyshire b_line Card Holders Holders Card b_line Derbyshire This publication is available in other formats from from formats other in available is publication This most local bus services (Wayfarer cannot be purchased on the train). the on purchased be cannot (Wayfarer services bus local most eastmidlandstrains.co.uk/derwentvalleyline and other staffed stations, from Tourist Information Centres and on on and Centres Information Tourist from stations, staffed other and 01629 538062 538062 01629 for seniors or child. Tickets can be purchased at Derby, Long Eaton Eaton Long Derby, at purchased be can Tickets child. or seniors for Hall Matlock DE4 3AG. 3AG. DE4 Matlock Hall except on Sundays. Adult tickets £13.00 including one child, £6.50 £6.50 child, one including £13.00 tickets Adult Sundays. on except Council, Economy, Transport and Communities Department, County County Department, Communities and Transport Economy, Council, travel before 0900 Monday to Saturday or on the Transpeak bus bus Transpeak the on or Saturday to Monday 0900 before travel Derwent Valley Line Community Rail Partnership, Derbyshire County County Derbyshire Partnership, Rail Community Line Valley Derwent train services in Derbyshire and the Peak District. Not valid for rail rail for valid Not District. Peak the and Derbyshire in services train day rover tickets are valid on most bus and and bus most on valid are tickets rover day Derbyshire Wayfarer Derbyshire tourism and railway organisations. -

7-Night Peak District Self-Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Peak District Self-Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Self-Guided Walking Destinations: Peak District & England Trip code: DVPOA-7 1, 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Enjoy a break in the Peak District with the walking experts; we have all the ingredients for your perfect Self- Guided Walking holiday. Our 3-star country house, just a few minutes' walk from the limestone gorge of Dove Dale, is geared to the needs of walkers and outdoor enthusiasts. Enjoy hearty local food, detailed route notes, and an inspirational location from which to explore the stunning landscapes of the Derbyshire Dales. HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Use our Discovery Point, stocked with maps and walks directions for exploring the local area • Head out on any of our walks to discover the varied beauty of the Peak District on foot • Enjoy panoramic views from gritstone edges • Admire stunning limestone dales • Visit classic viewpoints, timeless villages and secret corners • Look out for wildlife and learn about the 'Peaks' history • Choose a relaxed pace of discovery where you can get some fresh air in one of England's finest walking www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 areas • Cycle along the nearby Tissington Trail • Discover Chatsworth House • Visit the Alton Towers theme park TRIP SUITABILITY Explore at your own pace and choose the best walk for your pace and ability. ACCOMMODATION The Peveril Of The Peak The Peveril of the Peak, named after Sir Walter Scott’s novel, stands proudly in the Peak District countryside, close to the village of Thorpe. -

Buxton Museum Apps

COLLECTIONS IN THE LANDSCAPE PILOT PROJECT BUXTON MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY Evaluation Report April 24 2014 Creating Cultural Capital Lord Cultural Resources is a global professional practice dedicated to creating cultural capital worldwide. We assist people, communities and organizations to realize and enhance cultural meaning and expression. We distinguish ourselves through a comprehensive and integrated full-service offering built on a foundation of key competencies: visioning, planning and implementation. We value and believe in cultural expression as essential for all people. We conduct ourselves with respect for collaboration, local adaptation and cultural diversity, embodying the highest standards of integrity, ethics and professional practice. We help clients clarify their goals; we provide them with the tools to achieve those goals; and we leave a legacy as a result of training and collaboration. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 2. Evaluation .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 The Process Of Creating Content ................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Participant Feedback .................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Social Media And Marketing ...................................................................................................... -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Ancient Defensive Earthworks Fortified

CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF LONDON. SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. 1903. COMMITTEE FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. LORD BALCARRES, M.P., F.S.A., Chairman. W. J. ANDREW, F.S.A. F. HAVERFIELD, F.S.A., MA. F. W. ATTREE (Lt.-Col. R.E.), W. H. ST. J. HOPE, M.A. F.S.A. BOYD DAWICINS (Prof.), F.R.S., J. HORACE ROUND, M.A. F.S.A. SIR JOHN EVANS, K.C.B., F.R.S., O. E. RUCK (Lt.-Col. RE.), V.P.S.A. F.S.A.Sc. A. R. GODDARD, B.A. W. M. TAPP, LL.D. BERTRAM C. A. WINDLE (Prof.), F.R.S., F.S.A. I. CHALKLEY GOULD, Hon. Sec. {Royal Societies' Club, St. James's Street, London.) EXTRACT from the Report of the Provisional Committee to the Congress of Archaeological Societies :— "There is need, not only for schedules such as this Committee is appointed to secure, but also for active antiquaries in all parts of the country to keep keen watch over ancient fortifications of earth and stone, and to endeavour to prevent their destruction by the hand of man in this utilitarian age." SCHEME FOR RECORDING ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. » T the Congress of the Archaeological Societies, held on A July ioth, 1901, a Committee was appointed to prepare a scheme for a systematic record of ANCIENT DEFENSIVE EARTHWORKS AND FORTIFIED ENCLOSURES. It was suggested that the secretaries of the various archaeological societies, and other gentlemen likely to be interested in the subject, should be pressed to prepare schedules of the works in their respective districts, in the hope that lists may eventually be published. -

Edale: a Study of a Pennine Dale

Scottish Geographical Magazine ISSN: 0036-9225 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsgj19 Edale: A study of a Pennine Dale C. B. Fawcett B.Litt., M.Sc. To cite this article: C. B. Fawcett B.Litt., M.Sc. (1917) Edale: A study of a Pennine Dale , Scottish Geographical Magazine, 33:1, 12-25, DOI: 10.1080/00369221708734256 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00369221708734256 Published online: 28 Jun 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 27 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsgj20 Download by: [University of California Santa Barbara] Date: 18 June 2016, At: 02:09 12 SCOTTISH GEOGRAPHICAL MAGAZINE. EDALE: A STUDY OF A PENNINE DALE.1 By C. B. FAWCETT, B.Litt., M.Sc. (With Sketch-Map and Figures.) THE dale marked on the large-scale maps of the High Peak District as the "Vale of Edale" is the high-lying valley along the south- eastern side of the Peak. From the heights above Dalehead to Edale End the valley stretches for nearly five miles in a line from west-south- west to east-north-east. In its widest parts the breadth from crest to crest reaches three miles ; but most of this is moorland, and the width of the habitable portion nowhere exceeds one mile, and averages little more than half that distance. The total area of the civil parish of Edale is eleven square miles, of which the greater part is uncultivated and uninhabited moorland. -

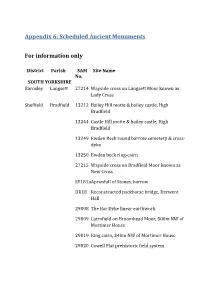

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Castleton Parish Statement (Draft)

Castleton Parish Statement (draft) Introduction Castleton is a vibrant village in the heart of the magnificent Peak District National Park. It has a rich blend of history in the centre of one of the most popular locations for walkers, whether they are casual walkers or experienced fell trekkers. There is a range of pubs, cafes, and other eating places to suit everyone's tastes during and at the end of an active day. Geography Castleton village is situated at the head of the Hope Valley. It straddles the white peak (limestone to the south) and the dark peak (millstone grit to the north). It is right at the heart of some of the most attractive scenery in the Peak District National Park (PDNP). Mam Tor and Lose Hill look down on the village and the iconic Winnats Pass which is on one of two roads in/out of the village. Winnats Pass provides access to the west – Buxton, Chapel-en-le- Frith, Manchester and Manchester Airport. The other road in/out of Castleton is down the Hope Valley to Hope village, Hathersage, Sheffield and Derby. Castleton Parish Statement (draft) History Looking down on Castleton is Peveril Castle which dates from the 11th Century and was built to protect the local lead mining and hunting. Lead mining was carried out by the Romans. A small settlement (Pechesers) was recorded at Peak Cavern in 1086 (The Domesday Book) and the planned village was probably laid out in the 12th century. Villagers There are between 500 and 600 permanent residents, there are many elderly residents and only a few families with children. -

Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley

High Peak and Hope Valley January – April 2020 Community Rail Partnership Guided Walks and Folk Trains in the High Peak and Hope Valley Welcome to this guide It contains details of Guided Walks and Folk Trains on the Hope Valley, Buxton and Glossop railway lines. These railway lines give easy access to the beautiful Peak District. Whether you fancy a great escape to the hills, or a night of musical entertainment, let the train take the strain so you can concentrate on enjoying yourself. High Peak and Hope Valley This leaflet is produced by the High Peak and Hope Valley Community Rail Partnership. Community Rail Partnership Telephone: 01629 538093 Email: [email protected] Telephone bookings for guided walks: 07590 839421 Line Information The Hope Valley Line The Buxton Line The Glossop Line Station to Station Guided Walks These Station to Station Guided Walks are organised by a non-profit group called Transpeak Walks. Everyone is welcome to join these walks. Please check out which walks are most suitable for you. Under 16s must be accompanied by an adult. It is essential to have strong footwear, appropriate clothing, and a packed lunch. Dogs on a short leash are allowed at the discretion of the walk leader. Please book your place well in advance. All walks are subject to change. Please check nearer the date. For each Saturday walk, bookings must be made by 12:00 midday on the Friday before. For more information or to book, please call 07590 839421 or book online at: www.transpeakwalks.co.uk/p/book.html Grades of walk There are three grades of walk to suit different levels of fitness: Easy Walks Are designed for families and the occasional countryside walker.