Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derbyshire T-Government Management Board

10. DERBYSHIRE T-GOVERNMENT MANAGEMENT BOARD 1. TERMS OF REFERENCE (i) Developing policy and priority Issues in the approach to developing e-government for Derbyshire (ii) To agree the allocation of the ODPM Government on –line grant (iii) To agree the engagement of consultants, staff secondments and use of resources for developmental work on core e- government projects (iv) To agree standards and protocols for joint working and information sharing between authorities. (v) Consider and agree option appraisals and business solutions that will meet common goals. (vi) Recommend and agree procurement arrangements (vii) Determine, where appropriate, lead authority arrangements (viii) Consider any budget provision that individual authorities may need to contribute towards the costs or resource needs of the partnership (ix) Consult the Derbyshire e-government partnership forum on progress (x) To nominate as appropriate representatives of the Board to steer the development of individual E-Government projects (xi) To consider and pursue additional resource funding from Government, EU or other sources and any match funding implications 2. MEMBERSHIP One member together with the Head of Paid Service or Chief Executive from each of the following constituent authorities:- Derbyshire County Council (Lead Authority), Derby City Council, North East Derbyshire District Council, the District of Bolsover, Chesterfield Borough Council, Amber Valley District Council, Erewash Borough Council, South Derbyshire District Council, Derbyshire Dales District Council, High Peak Borough Council, Derbyshire Police Authority, Derbyshire Fire Authority 4/10/1 Named substitutes for any of the above The Peak District National Park Authority be provided with a watching brief 2. FINANCE The Board shall operate under the Financial Regulations and Contract Standing Orders of Derbyshire Council the Lead Authority. -

Dovedale Primary Admission Arrangements 2019-2020

Willows Academy Trust Published Admissions Criteria Aiming HighTogether Dovedale Primary School Dovedale Primary School is part of Willows Academy Trust. As an academy, we are required to set and publish our own admissions criteria. Admission applications are managed through the Derbyshire Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme and are in line with the Derbyshire Admission arrangements for community and voluntary controlled schools. Individual pupils who have a statement of special educational needs which names Dovedale Primary School will be admitted. In deciding on admissions to Dovedale Primary School, the following order of priority will be adopted. 1. Looked after children and children who were looked after but ceased to be so because they were adopted (or became subject to a residence order or special guardianship order). 2. Children living in the normal area served by the school at the time of application and admission who have brothers or sisters attending the school at the time of application and admission. 3. Children living in the normal area served by the school at the time of application and admission. 4. Children not living in the normal area served by the school but who have brothers or sisters attending the school at the time of application and admission. 5. Other children whose parents have requested a place. Where, in the case of 2, 3, 4 or 5 above, choices have to be made between children satisfying the same criteria, those children living nearest to the school will be given preference. We reserve the right to withdraw any offer of a school place which has been obtained as a result of misleading or fraudulent information. -

Tideswell Parish Council Minutes of the Meeting of the Council Held on Monday 9Th January 2017

TIDESWELL PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 9TH JANUARY 2017 PRESENT: - Cllrs, R Baraona, J Bower, J Chapman, D Horne, J Kilner, D Whitehouse, Hannah Owen (Clerk) and 7 members of the public. 01.01.17 APOLOGIES Cllr Cadenhead and Cllr Andrew 01.01.17 VARIATION OF BUSINESS No Variation of Business 01.01.17 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Cllr Kilner declared an interest in Agenda item 13 Finance. 04.01.17 PUBLIC SPEAKING Members of the Public attended the Parish Council meeting to raise concerns about a potential housing development. The Parish Council are yet to be updated on this and have received no plans. Isabel Frenzel from Derbyshire Dales District Council is attending the February meeting to update the Parish Council. 05.01.17 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING The Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Monday 5th December 2016 were proposed as correct by Cllr Whitehouse, seconded Cllr Chapman, and all unanimously agreed. 06.01.17 DETERMINE IF ANY ITEMS ARE TO BE MOVED TO PART II CONFIDENTIAL No items moved to confidential. 07.01.17 CHAIRS ANNOUNCEMENTS The Chairman thanked everyone for their hard work in the taking down of the Christmas Lights. Cllr Chapman and Cllr Baraona were thanked for their hard work and many hours work organising and coordinating the event. A note will be placed in the Village Voice to thank the volunteers who also attended to help. 08.01.17 VILLAGE REPORTS (a) Play Areas – Mick Fletcher has visited the Playgrounds and will be beginning the playground repair work shortly. -

Visitor Economy Plan 2015-2019.Pdf

1 CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Value of the Visitor Economy 3 3. Visitor Perceptions and Behaviours 5 4. Strategic Fit 6 5. Current Offer and Opportunities for Growth 8 6. Growing the Value of the Visitor Economy 9 7. Priorities and Actions 12 8. Measures of Success 14 2 1. Introduction A strong visitor economy is important to the economic health of the Derbyshire Dales. Generating an estimated £315m in visitor spend it provides employment, offers business opportunities and helps sustain local services – but there is room for growth. To grow the value of the sector visitors need to be encouraged to spend more when they come. Promoting the special qualities of the Dales, improving the visitor ‘welcome’, providing better experiences and working towards a higher value visitor offer will help achieve this. This plan takes its lead from the District Council’s Economic Plan. Drawing on the area’s distinctive rural offer, proximity to urban markets and already high visitor numbers (relative to other Derbyshire districts), the aim of the plan is: AIM: To develop a higher value visitor economy in the Derbyshire Dales Doing everything needed to achieve this aim is a ‘big ask’ of the District Council and is not the purpose of this plan. Rather, within the context of available resources, effort will be focused on three priorities where District Council intervention can make a difference, complementing and adding to the activities of our partners and other stakeholders: PRIORITIES: 1. Support businesses within the visitor economy to exploit key markets and supply chain opportunities 2. -

Wirral Ramblers

WIRRAL RAMBLERS SUNDAY 26th May 2013 Castleton Area (Castleton) A WALK Departing Castleton center, we ascend Mam Tor via Speedwell Cavern and over Windy Knoll. Along to Hollins Cross, Lose Hill, down to Bagshaw Bridge to walk up to the Roman Road and through Woodlands Valley to Lady Bower Reservoir. We return to Castleton via Winhill Pike, Thornhill Carrs, Aston Hall, past Hope Cemetery, taking the fields back into the town. DISTANCE: 24km (14.75 miles) 20 POINTS ASCENT 812m (2664ft) B+ WALK Starting from Sparrowpit on the A623 we follow footpaths to Rushop Hall and on to the start of the Pennine Bridleway at the western point of Rushup Edge. We follow the bridleway as far as South Head where we turn NE to Jacob’s Ladder, the Pennine Way and descending to Barber Booth. After crossing fields and a short road walk up a footpath to Mam Tor, Hollins Cross then descend back to Castleton. DISTANCE: 19.7km (12 miles) 16 POINTS ASCENT 618m (2028ft) B- WALK Starting from Castleton car park we travel E towards Speedwell Cavern then N by Treak Cliff Cavern on to Man Tor. We then take the path along Rushup Edge with stunning views from both valleys. We turn W along Chapel Gate track through Barber Booth on to Edale, then through fields towards Lady Booth Farm, we then turn S on to Hollins Cross and follow path into Castleton DISTANCE 15.5k (9.5 miles) 12 POINTS ASCENT 380m (1140ft) C WALK From Castleton W, then NW along Odin Sitch, past Woodseats, before climb to Hollins Cross. -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

Derbyshire and Derby City Agreed Syllabus for Religious Education 2020–2025

Derbyshire and Derby City Agreed Syllabus for Religious Education 2020–2025 Public 20/04/2020 Public 20/04/2020 i Written by Stephen Pett, Kate Christopher, Lat Blaylock, Fiona Moss, Julia Diamond-Conway Images, including cover images, courtesy of NATRE/Spirited Arts © NATRE Published by RE Today Services, 5–6 Imperial Court, 12 Sovereign Road, Birmingham, B30 3FH © RE Today 2019. This syllabus was written by RE Today Services and is licensed to Derbyshire and Derby City SACRE for use in the schools in Derbyshire and Derby City for 2020–2025. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to schools in Derbyshire and Derby City to photocopy pages for classroom use only. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, recorded or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Derbyshire and Derby City Agreed Syllabus for RE, 2020–2025 © RE Today Services 2019 Public 20/04/2020 ii Contents page: Page Foreword 1 Introduction 2 A What is RE for? A1 The purpose of RE 6 A2 The aim(s) of RE 7 A3 How to use this agreed syllabus: 12 steps 8 B What do we need to do? B1 Legal requirements 11 B2 What religions are to be taught? 13 B3 Time for religious education 14 C What do pupils learn in RE? C1 Religious Education key questions: an overview 16 C2 RE in EYFS Programme of Study 19 EYFS Units of Study 23 C3 RE in KS1 Programme of Study and planning steps 31 KS1 Units of study 35 C4 RE in KS2 Programme of Study and planning steps 45 Lower KS2 Units -

Edale Circular (Via Kinder Scout and Mam Tor)

Edale Circular (via Kinder Scout and Mam Tor) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 20th August 2018 Current status Document last updated Friday, 24th August 2018 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2017-2018, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Edale Circular (via Kinder Scout and Mam Tor) Start: Edale Station Finish: Edale Station Edale Station, map reference SK 122 853, is 236 km north west of Charing Cross and 244m above sea level, and in Derbyshire. Length: 20.6 km (12.8 mi), of which 3.2 km (2.0 mi) on tarmac or concrete. Cumulative ascent/descent: 843m. For a shorter walk, see below Walk options. Toughness: 10 out of 10 Time: 5 ¾ hours walking time. -

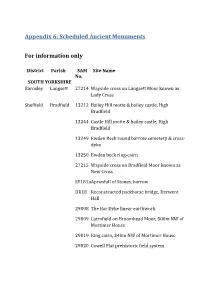

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Simon John Kitcher MPhysGeog May 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated, and that it has not been previously submitted in application for any other degree at any other educational institution in the United Kingdom or overseas. ii Abstract Sub-fossil pollen from Holocene tufa pool sediments is used to investigate middle – late Holocene environmental conditions in the White Peak region of the Derbyshire Peak District in northern England. The overall aim is to use pollen analysis to resolve the relative influence of climate and anthropogenic landscape disturbance on the cessation of tufa production at Lathkill Dale and Monsal Dale in the White Peak region of the Peak District using past vegetation cover as a proxy. Modern White Peak pollen – vegetation relationships are examined to aid semi- quantitative interpretation of sub-fossil pollen assemblages. Moss-polsters and vegetation surveys incorporating novel methodologies are used to produce new Relative Pollen Productivity Estimates (RPPE) for 6 tree taxa, and new association indices for 16 herb taxa. RPPE’s of Alnus, Fraxinus and Pinus were similar to those produced at other European sites; Betula values displaying similarity with other UK sites only. RPPE’s for Fagus and Corylus were significantly lower than at other European sites. Pollen taphonomy in woodland floor mosses in Derbyshire and East Yorkshire is investigated. -

Castleton and Hope’S Medieval and Later Past with This Self-Guided Trail

Explore Castleton and Hope’s medieval and later past with this self-guided trail. You will CASTLETON discover the history behind the landscape and its routeways, fields, lead mines, defences and buildings. This trail is the result of the research and HOPE of members of Hope and Castleton Historical Societies and other volunteers. Medieval Historical Landscape Start and Finish: Castleton Visitor Centre pay a self-guided trail and display car park, grid ref. SK149830. Distance: 4½ miles / 7 km. Time: Allow 3 hours. Difficulty: Moderate. Route: The route is along paved lanes and across pasture fields, which in places become muddy after rain. There are a number of step stiles along the route, some difficult for dogs. Suitable walking boots and outdoor clothing are advised. Please carry the Ordnance Survey Explorer Map OL1 Dark Peak with you for navigation. 1 Town Ditch Road. As you walk you can see the Look over the stream and wall by the valley’s surrounding hills – Mam Tor with car park entrance for the embankment its distinctive landslip, Back Tor, Losehill in the small field. This is Castleton’s and Winhill. Stop a few paces after the town ditch and you are just outside the bridge. medieval village. The ditch was built during medieval times to protect the village and possibly collect taxes and tolls. Castleton appears in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Pechesers. Castleton is first recorded as the village name in Odin Sough. 1275. Peveril Castle was built soon after the Norman Conquest by the baron Odin Sough William Peverel to administer the Royal 3 Odin Sough runs under the hedge and Forest of the High Peak. -

NOTICE of POLL and SITUATION of POLLING STATIONS Election of A

NOTICE OF POLL and SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS High Peak Borough Council Election of a Derbyshire County Councillor for Chapel & Hope Valley Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Chapel & Hope Valley Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BANN 31 Beresford Road, Independent Barton Sarah L(+) Barton Michael(++) Paddy Chapel-en-le-Frith, High Peak, SK23 0NY COLLINS 9 Hope Road, The Green Party Wight Jeremy P(+) Farrell Charlotte N(++) Joanna Wiehe Edale, Hope Valley, S33 7ZF GOURLAY Ashworth House, The Conservative and Sizeland Kathleen(+) Gourlay Sara M(++) Nigel Wetters Long Lane, Unionist Party Chapel-en-le-Frith, High Peak, SK23 0TF HARRISON Castleton Hall, Labour Party Cowley Jessica H(+) Borland Paul J(++) Phil Castle Street, Castleton, Hope Valley, S33 8WG PATTERSON (Address in High Peak) Liberal Democrats Rayworth Jayne H(+) Foreshew-Cain James Robert Stephen J(++) 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled