THEME: IMAGES of POWER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Plataran Borobudur Encounter

PLATARAN BOROBUDUR ENCOUNTER ABOUT THE DESTINATION Plataran Borobudur Resort & Spa is located within the vicinity of ‘Kedu Plain’, also known as Progo River Valley or ‘The Garden of Java’. This fertile volcanic plain that lies between Mount Sumbing and Mount Sundoro to the west, and Mount Merbabu and Mount Merapi to the east has played a significant role in Central Javanese history due to the great number of religious and cultural archaeological sites, including the Borobudur. With an abundance of natural beauty, ranging from volcanoes to rivers, and cultural sites, Plataran Borobudur stands as a perfect base camp for nature, adventure, cultural, and spiritual journey. BOROBUDUR Steps away from the resort, one can witness one the of the world’s largest Buddhist temples - Borobudur. Based on the archeological evidence, Borobudur was constructed in the 9th century and abandoned following the 14th-century decline of Hindu kingdoms in Java and the Javanese conversion to Islam. Worldwide knowledge of its existence was sparked in 1814 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, then the British ruler of Java, who was advised of its location by native Indonesians. Borobudur has since been preserved through several restorations. The largest restoration project was undertaken between 1975 and 1982 by the Indonesian government and UNESCO, following which the monument was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Borobudur is one of Indonesia’s most iconic tourism destinations, reflecting the country’s rich cultural heritage and majestic history. BOROBUDUR FOLLOWS A remarkable experience that you can only encounter at Plataran Borobudur. Walk along the long corridor of our Patio Restaurants, from Patio Main Joglo to Patio Colonial Restaurant, to experience BOROBUDUR FOLLOWS - where the majestic Borobudur temple follows you at your center wherever you stand along this corridor. -

Benin Kingdom • Year 5

BENIN KINGDOM REACH OUT YEAR 5 name: class: Knowledge Organiser • Benin Kingdom • Year 5 Vocabulary Oba A king, or chief. Timeline of Events Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means 900 CE Lots of villages join together and make a “Rulers of the Sky”. kingdom known as Igodomigodo, ruled by Empire lots of countries or states, all ruled by the Ogiso. one monarch or single state. c. 900- A huge earthen moat was constructed Guild A group of people who all do the 1460 CE around the kingdom, stretching 16.000 km same job, usually a craft. long. Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 1180 CE The Oba royal family take over from the Voodoo The belief that non-human objects Osigo, and begin to rule the kingdom. (or Vodun) have spirits or souls. They are treated like Gods. Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as 1440 CE Benin expands its territory under the rule of Oba Ewuare the Great. a kind of money to trade with African leaders. 1470 CE Oba Ewuare renames the kingdom as Civil war A war between people who live in the Edo, with it;s main city known as Ubinu (Benin in Portuguese). same country. Moat A long trench dug around an area to 1485 CE The Portuguese visit Edo and Ubinu. keep invaders out. 1514 CE Oba Esigie sets up trading links with the Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Portuguese, and other European visitors. country by force, and live among the 1700 CE A series of civil wars within Benin lead to people. -

TIBETAN BUDDHISM Philosophy/Religion PR326 Dr

TIBETAN BUDDHISM Philosophy/Religion PR326 Dr. Joel R. Smith Spring, 2016 Skidmore College A study of classical and contemporary Tibetan thinkers who see philosophy as intertwined with religious practice. The course focuses on the Vajrayana form of Mahayana Buddhism that is the central element in the culture of Tibet, as well as its Mahayana Buddhist background in India. Emphasis is on the central ideas of wisdom, compassion, emptiness, and dependent arising. Texts: 1. Keown, Damien, Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). ISBN 978-0-19- 966383-5 2. Kapstein, Matthew T., Tibetan Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). ISBN 978-0-19-973512-9 **3. Lopez, Donald S., Jr., ed., Religions of Tibet in Practice: Abridged Edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007). ISBN 978-0-691-12972-378 4. Powers, John, A Concise Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, (Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 2008). ISBN 978-1-55939-296-9 5. Santideva, A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life (Bodhicaryavatara), tr. Vesna A. Wallace & B. Alan Wallace (Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications, 1997). ISBN 978-1-55939-061-1 6. Tsering, Geshe Tashi, Emptiness (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2009). ISBN 978-086171-511-3 7. Yeshe, Lama Thubten, Introduction to Tantra: The Transformation of Desire (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001). ISBN 978-161-4291558 I will be delighted to talk with you outside of class. Make an appointment to see me or come by during my office hours. Office: Ladd 217. Email: [email protected] Office phone: 580-5407 (Please do not call me at home.) Office hours: Monday and Wednesday: 4:30-5:30 Tuesday and Thursday: 3:30-4:30 (other times Friday: 1:00-2:00 by appointment) THE BUDDHIST BACKGROUND IN INDIA: THERAVADA AND MAHAYANA Jan 25: Introduction to the course; Powers, Introduction & The Indian Background (Ch. -

Medieval India

A History of Knowledge Oldest Knowledge What the Jews knew What the Sumerians knew What the Christians knew What the Babylonians knew Tang & Sung China What the Hittites knew Medieval India What the Persians knew What the Japanese knew What the Egyptians knew What the Muslims knew What the Indians knew The Middle Ages What the Chinese knew Ming & Manchu China What the Greeks knew The Renaissance What the Phoenicians knew The Industrial Age What the Romans knew The Victorian Age What the Barbarians knew The Modern World 1 Medieval India Piero Scaruffi 2004 2 What the Indians knew • Bibliography – Gordon Johnson: Cultural Atlas of India (1996) – Henri Stierlin: Hindu India (2002) – Hermann Goetz: The Art of India (1959) – Heinrich Zimmer: Philosophies of India (1951) – Surendranath Dasgupta: A History of Indian Philosophy (1988) – Richards, John: The Mughal Empire (1995) 3 India • 304 BC - 184 BC: Maurya • 184 BC - 78 BC: Sunga • 78 AD -233: Kushan • 318 - 528: Gupta • 550 - 1190 : Chalukya • Hoysala (1020-1342) • 1192-1526: Delhi sultanate • 1526-1707: Moghul • 1707-1802: Maratha 4 What the Indians knew • Tantra – Ancient practice to worship the mother goddess through sexual intercourse – Group intercourse 5 What the Indians knew • Tantra – Esoteric Hinduism – Dialogues between the god Shiva and his wife Parvati – Reversals of Hindu social practices (e.g., incest) – Reversals of physiological processes – Forbidden substances are eaten and forbidden sexual acts are performed ritually – ”Five m's": maithuna ("intercourse"), matsya ("fish"), -

418338 1 En Bookbackmatter 205..225

Glossary Abhayamudra A style of keeping hands while sitting Abhidhama The Abhidhamma Pitaka is a detailed scholastic reworking of material appearing in the Suttas, according to schematic classifications. It does not contain systematic philosophical treatises, but summaries or enumerated lists. The other two collections are the Sutta Pitaka and the Vinaya Pitaka Abhog It is the fourth part of a composition. The last movement gradually goes back to the sthayi after completion of the paraphrasing and improvisation of the composition, which can cover even three octaves in the recital of a master performer Acharya A teacher or a tutor who is the symbol of wisdom Addhayoga One of seven kinds of lodgings where monks are allowed to live. Addhayoga is a building with a roof sloping on either one side or both. It is shaped like wings of the Garuda Agganna-sutta AggannaSutta is the 27th Sutta of the Digha Nikaya collection. The sutta describes a discourse imparted by the Buddha to two Brahmins, Bharadvaja, and Vasettha, who left their family and caste to become monks Ahankar Haughtiness, self-importance A-hlu-khan mandap Burmese term, a temporary pavilion to receive donation Akshamala A japa mala or mala (meaning garland) which is a string of prayer beads commonly used by Hindus, Buddhists, and some Sikhs for the spiritual practice known in Sanskrit as japa. It is usually made from 108 beads, though other numbers may also be used Amulets An ornament or small piece of jewellery thought to give protection against evil, danger, or disease. Clay tablets have also been used as amulets. -

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, and the NEGOTIATION of the PUBLIC SPHERE by Leana Marie Rudolph a Capstone Project Submitted for Graduatio

BUDDHISM, MEDITATION, AND THE NEGOTIATION OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE By Leana Marie Rudolph A capstone project submitted for Graduation with University Honors May 20, 2021 University Honors University of California, Riverside APPROVED Dr. Matthew King Department of Religious Studies Dr. Richard Cardullo, Howard H Hays Jr. Chair University Honors ABSTRACT This capstone serves to map and gather the oral histories of formerly undocumented Buddhist communities pertaining to their lived experiences in the Inland Empire. The ethnographic fieldwork conducted of 11 sites over the period of 12 months explored the intersection of diaspora, economy, and religious affiliation. This research begins to explore this junction by undertaking a qualitative and quantitative study that will map Buddhist life in the Inland Empire today. It will include interviews, providing oral histories, and will be accessible through a GIS map, helping Religious Studies and Anthropologist scholars to locate these sites and have background information on these locations. The Inland Empire represents many heavily populated, post-agricultural, and manufacturing areas in America today, which since the 1970s and especially since 2008 has suffered from many economic and social crises related to suburban poverty, as well as waves of demographic changes. Taking the Inland Empire as a petri dish for broader trends at the intersection of religion, economy, and the social in the American public sphere today, this capstone project hopes to determine how Buddhism forms at these intersections, what new stories about life in the Inland Empire Buddhist sites and communities help illuminate, and what forms of digital interfacing best brings anthropological analyses to the publics it examines. -

Goddess Lakshmi Goddess Lakshmi Is Vishnu’S Concert

Tri Murthis: The Three Gods The Indian culture consisting of Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, Epics and the classical books explain that there are three Gods: Brahma Vishnu Maheswara Each of them has been identified with specific functions in the Universe. Brahma, the Creator Four-faced God Brahma is called Chaturmukha Brahma. He has taken birth from the Lotus flower which came out of the navel of Bhagavan Vishnu. He has four faces and four hands. He holds the four Vedas in one of His hands. He is seated on Lotus. The story of Brahma is the story of Creation. Brahma is the beginning. He is the Origin of all the Creation. This is sum and substance of the story of Creation as available in all the sacred books of India (Vedas and Shastras). Hamsa (Swan) is his vehicle. Goddess Saraswati Goddess Saraswati is Brahma’s consort. She is Goddess for Vidya or education and learning. She also grants Jnaana (Knowledge and Wisdom). Brahma granted boons to many asuras (demons) in the past because they did penance or tapasya for Brahma’s appearance. He gave them what ever boons they wanted. Some asuras like Hiranya Kashipa, became violent and cruel. Lord Vishnu had to incarnate on earth and kill these asuras who troubled the devataas, lokas and even the ordinary human beings. Vishnu, the Protector Vishnu is the God who protects the Universe. He took ten avataras (births or incarnations) to save the earth, to protect the good people and to punish the persons doing wrong deeds. Vishnu is also called Shesha Sayana. -

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

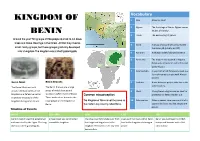

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN Arrive Yokohama: 0800 Sunday, January 27 Onboard Yokohama: 2100 Monday, January 28 Arrive Kobe: 0800 Wednesday, January 30 Onboard Kobe: 1800 Thursday, January 31 Brief Overview: The "Land of the Rising Sun" is a country where the past meets the future. Japanese culture stretches back millennia, yet has created some of the latest modern technology and trends. Japan is a study in contrasts and contradictions; in the middle of a modern skyscraper you might discover a sliding wooden door which leads to a traditional chamber with tatami mats, calligraphy, and tea ceremony. These juxtapositions mean you may often be surprised and rarely bored by your travels in Japan. Voyagers will have the opportunity to experience Japanese hospitality first-hand by participating in a formal tea ceremony, visiting with a family in their home in Yokohama or staying overnight at a traditional ryokan. Japan has one of the world's best transport systems, which makes getting around convenient, especially by train. It should be noted, however, that travel in Japan is much more expensive when compared to other Asian countries. Japan is famous for its gardens, known for its unique aesthetics both in landscape gardens and Zen rock/sand gardens. Rock and sand gardens can typically be found in temples, specifically those of Zen Buddhism. Buddhist and Shinto sites are among the most common religious sites, sure to leave one in awe. From Yokohama: Nature lovers will bask in the splendor of Japan’s iconic Mount Fuji and the Silver Frost Festival. Kamakura and Tokyo are also nearby and offer opportunities to explore Zen temples and be led in meditation by Zen monks. -

E:\Jurnal Bumi Lestari\EDISI FE

Niken Wirasanti : The Sugnificance Of Sacred Places From “The Triad” Of Mendut Temple - ..... THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SACRED PLACES FROM “THE TRIAD” OF MENDUT TEMPLE – PAWON TEMPLE – BOROBUDUR TEMPLE : PERSPECTIVE OF ENVIRONMENTAL SEMIOTIC Niken Wirasanti*), Timbul Haryono*), Sutikno**) *) Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Gadjah Mada University **) Faculty of Geography, Gadjah Mada University [email protected] Abstrak Letak Candi Mendut - Candi Pawon -Candi Borobudur berada dalam satu garis (imajiner) yang dikenal dengan tiga serangkai. Rangkaian tersebut merupakan sistem tanda yang oleh masyarakat Mataram Kuna abad IX Masehi diberi makna sesuai dengan konvensi yang berlaku pada waktu itu. Membuktikan ketiga candi yang merupakan sistem tanda dengan sebuah makna dapat dijelaskan dengan pendekatan semiotika struktural (Ferdinan de Saussure) yang mendasarkan pada elemen- elemen semiotika yaitu tanda (penanda-petanda), dan poros tanda (sintagmatik dan paradigmatik). Elemen tanda dari lingkungan yang dapat dirunut yaitu penanda ruang, elevasi, jenis tanah, dan sumber air, sedangkan elemen tanda dari candi yaitu arsitektur, arca, dan relief cerita. Tanda tersebut tidak dapat dilihat secara terpisah-pisah tetapi dilihat dalam relasi dengan tanda yang lain dalam poros sintagmatik dan paradigmatik. Untuk itu urutan tanda dimulai dari Candi Mendut-Candi Pawon- Candi Borobudur yang tersusun dalam susunan tertentu (jukstaposisi) dengan masing- masing makna simbolisnya. Tanda-tanda pada Candi Mendut – Candi Pawon – Candi Borobudur yaitu lokasi, tanah- batuan, sumber air, elevasi, arca, dan relief cerita, tersusun dalam rangkaian yang memperlihatkan sebuah struktur yang bermakna. Susunan tersebut bersifat linier yakni mengikuti aturan tertentu. Apabila aturan penataan tersebut berubah maka maknanyapun akan berbeda. Hal inilah yang membuktikan bahwa ketiga candi tersebut membentuk kesatuan rangkaian perlambang yang mengacu pada makna simbolis berdasarkan konsep ajaran agama Buddha pada masa Mataram Kuna abad IX Masehi.