Observations of Twenty-Five Years As a United States Circuit Judge Donald P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 15, 1988

REPORT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE JLlDlClAL CONFERENCE OF THE UNITED STATES March 15, 1988 The Judicial Conference of the United States convened on March 15, 1988, pursuant to the call of the Chief Justice of the United States issued under 28 U.S.C. 331. The Chief Justice presided and the following members of the Conference were present: I First Circuit: Chief Judge Levin H. Campbell Chief Judge Juan M. Perez-Gimenez, District of Puerto Rico Second Circuit: Chief Judge Wilfred Feinberg Chief Judge John T. Curtin, Western District of New York Third Circuit: Chief Judge John J. Gibbons Chief Judge William J. Nealon, Jr., Middle District of Pennsylvania Fourth Circuit: L I Chief Judge Harrison L. Winter Judge Frank A. Kaufman, District of Maryland I Fifth Circuit: Chief Judge Charles Clark Chief Judge L. T. Senter, Jr., Northern District of Mississippi Sixth Circuit: Chief Judge Pierce Lively Chief Judge Phillip Pratt, Eastern District of Michigan Seventh Circuit: Chief Judge William J. Bauer Judge Sarah Evans Barker, Southern District of Indiana Eighth Circuit: Judge Gerald W. Heaney' Chief Judge John F. Nangle, Eastern District of Missouri Ninth Circuit: Chief Judge James R. Browning Chief Judge Robert F. Peckham, Northern District of California Tenth Circuit: Chief Judge William J. Holloway Chief Judge Sherman G. Finesilver, District of Colorado Eleventh Circuit: Chief Judge Paul H. Roney Chief Judge Sam C. Pointer, Jr., Northern District of Alabama District of Columbia Circuit: Chief Judge Patricia M. Wald Chief Judge Aubrey E. Robinson, Jr., District of Columbia *Designated by the Chief Justice in place of Chief Judge Donald P. -

International Society of Barristers Quarterly

International Society of Barristers Volume 52 Number 2 ATTICUS FINCH: THE BIOGRAPHY—HARPER LEE, HER FATHER, AND THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN ICON Joseph Crespino TAMING THE STORM: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JUDGE FRANK M. JOHNSON JR. AND THE SOUTH’S FIGHT OVER CIVIL RIGHTS Jack Bass TOMMY MALONE: THE GUIDING HAND SHAPING ONE OF AMERICA’S GREATEST TRIAL LAWYERS Vincent Coppola THE INNOCENCE PROJECT Barry Scheck Quarterly Annual Meetings 2020: March 22–28, The Sanctuary at Kiawah Island, Kiawah Island, South Carolina 2021: April 25–30, The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, Ireland International Society of Barristers Quarterly Volume 52 2019 Number 2 CONTENTS Atticus Finch: The Biography—Harper Lee, Her Father, and the Making of an American Icon . 1 Joseph Crespino Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights. 13 Jack Bass Tommy Malone: The Guiding Hand Shaping One of America’s Greatest Trial Lawyers . 27 Vincent Coppola The Innocence Project . 41 Barry Scheck i International Society of Barristers Quarterly Editor Donald H. Beskind Associate Editor Joan Ames Magat Editorial Advisory Board Daniel J. Kelly J. Kenneth McEwan, ex officio Editorial Office Duke University School of Law Box 90360 Durham, North Carolina 27708-0360 Telephone (919) 613-7085 Fax (919) 613-7231 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 52 Issue Number 2 2019 The INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BARRISTERS QUARTERLY (USPS 0074-970) (ISSN 0020- 8752) is published quarterly by the International Society of Barristers, Duke University School of Law, Box 90360, Durham, NC, 27708-0360. -

Race, Civil Rights, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit

RACE, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT By JOHN MICHAEL SPIVACK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by John Michael Spivack ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In apportioning blame or credit for what follows, the allocation is clear. Whatever blame attaches for errors of fact or interpretation are mine alone. Whatever deserves credit is due to the aid and direction of those to whom I now refer. The direction, guidance, and editorial aid of Dr. David M. Chalmers of the University of Florida has been vital in the preparation of this study and a gift of intellect and friendship. his Without persistent encouragement, I would long ago have returned to the wilds of legal practice. My debt to him is substantial. Dr. Larry Berkson of the American Judicature Society provided an essential intro- duction to the literature on the federal court system. Dr. Richard Scher of the University of Florida has my gratitude for his critical but kindly reading of the manuscript. Dean Allen E. Smith of the University of Missouri College of Law and Fifth Circuit Judge James P. Coleman have me deepest thanks for sharing their special insight into Judges Joseph C. Hutcheson, Jr., and Ben Cameron with me. Their candor, interest, and hospitality are appre- ciated. Dean Frank T. Read of the University of Tulsa School of Law, who is co-author of an exhaustive history of desegregation in the Fifth Cir- cuit, was kind enough to confirm my own estimation of the judges from his broad and informed perspective. -

United States Court of Appeals

United States Court of Appeals Fifth Federal Judicial Circuit Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas Circuit Judges Priscilla R. Owen, Chief Judge ...............903 San Jacinto Blvd., Rm. 434 ..................................................... (512) 916-5167 Austin, Texas 78701-2450 Carl E. Stewart ......................................300 Fannin St., Ste. 5226 ............................................................... (318) 676-3765 Shreveport, LA 71101-3425 Edith H. Jones .......................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12505 ................................... (713) 250-5484 Houston, Texas 77002-2655 Jerry E. Smith ........................................515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12621 ................................... (713) 250-5101 Houston, Texas 77002-2698 James L. Dennis ....................................600 Camp St., Rm. 219 .................................................................. (504) 310-8000 New Orleans, LA 70130-3425 Jennifer Walker Elrod ........................... 515 Rusk St., U.S. Courthouse, Rm. 12014 .................................. (713) 250-7590 Houston, Texas 77002-2603 Leslie H. Southwick ...............................501 E. Court St., Ste. 3.750 ........................................................... (601) 608-4760 Jackson, MS 39201 Catharina Haynes .................................1100 Commerce St., Rm. 1452 ..................................................... (214) 753-2750 Dallas, Texas 75242 James E. Graves Jr. ................................501 E. Court -

A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: a Century of Service

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 1 2007 A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2303 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Cover Page Footnote * This article is dedicated to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman appointed ot the U.S. Supreme Court. Although she is not a graduate of our school, she received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Fordham University in 1984 at the dedication ceremony celebrating the expansion of the Law School at Lincoln Center. Besides being a role model both on and off the bench, she has graciously participated and contributed to Fordham Law School in so many ways over the past three decades, including being the principal speaker at both the dedication of our new building in 1984, and again at our Millennium Celebration at Lincoln Center as we ushered in the twenty-first century, teaching a course in International Law and Relations as part of our summer program in Ireland, and participating in each of our annual alumni Supreme Court Admission Ceremonies since they began in 1986. -

Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Louisiana Law Review Volume 80 Number 4 Summer 2020 Article 9 11-11-2020 Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Ronald J. Scalise Jr., Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, 80 La. L. Rev. (2020) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol80/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Will Formalities in Louisiana: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Ronald J. Scalise, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................ 1332 I. A (Very Brief) History of Wills in the United States ................. 1333 A. Functions of Form Requirements ........................................ 1335 B. The Law of Yesterday: The Development of Louisiana’s Will Forms ....................................................... 1337 II. Compliance with Formalities ..................................................... 1343 A. The Slow Migration from “Strict Compliance” to “Substantial Compliance” to “Harmless Error” in the United States .............................................................. 1344 B. Compliance in Other Jurisdictions, Civil and Common .............................................................. -

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R

Mll I.-I CHIEF JUDGE JOHN R. BROWN John R. Brown is a native Nebraskan. He was born in the town of Holdredge on December 10, 1909. Judge Brown remained in Ne- braska through his undergraduate education and received an A.B. degree in 1930 from the University of Nebraska. The Judge's legal education was attained at the University of Michigan, from which he received a J.D. degree in 1932. Both of Judge Brown's alma maters have conferred upon him Honorary LL.D. degrees. The University of Michigan did so in 1959, followed by the University of Nebraska in 1965. During World War II, the Judge served in the United States Air Force. Judge Brown was appointed to the United States Court of Ap- peals by President Eisenhower in July, 1955. Twelve years later, in July, 1967, he became Chief Judge of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Since 1967 the Judge has represented the Fifth Circuit at the Judicial Conference of the United States, as well as having been a member of its executive committee since 1972. The Judge is also a member of the Houston Bar Association, the Texas Bar Association, the American Bar Association, and the Maritime Law Association of the United States. Judge Brown is married to the former Mary Lou Murray and has one son, John R., Jr. The Judge currently lives in Houston. i, iiI IVA JUDGE RICHARD T. RIVES Richard T. Rives was born in Montgomery, Alabama, on Janu- ary 15, 1895. He attended Tulane University in the years 1911 and 1912. -

The Fifth Circuit Four: the Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Divisio

The Fifth Circuit Four: The Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Division Historical Paper Length: 2,500 Words 1 “For thus saith the Lord God, how much more when I send my four sore judgments upon Jerusalem, the sword, and the famine, and the noisome beast, and the pestilence, to cut off from it man and beast.”1 In the Bible, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are said to usher in the end of the world. That is why, in 1964, Judge Ben Cameron gave four of his fellow judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit the derisive nickname “the Fifth Circuit Four” – because they were ending the segregationist world of the Deep South.2 The conventional view of the civil rights struggle is that the Southern white power structure consistently opposed integration.3 While largely true, one of the most powerful institutions in the South, the Fifth Circuit, helped to break civil rights barriers by enforcing the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, something that other Southern courts were reluctant to do.4 Despite personal and professional backlash, Judges John Minor Wisdom, Elbert Tuttle, Richard Rives, and John Brown played a significant but often overlooked role in integrating the South.5 Background on the Fifth Circuit The federal court system, in which judges are appointed for life, consists of three levels.6 At the bottom are the district courts, where cases are originally heard by a single trial judge. At 1 Ezekiel 14:21 (King James Version). -

Focus Questions for Unlikely Heroes

Focus Questions For Unlikely Heroes These focus questions are intended to aid you in the active reading of Jack Bass’s “Unlikely Heroes,” one of the books selected by the faculty of the Syracuse University College of Law to help prepare you for your time studying law. This book was chosen by Professor James Baker. The questions are written with the intention of helping you. You won’t be tested on your answers and you can feel free to read the book without them should you choose. And there aren’t any correct answers for these questions. It’s more important to question the text and reflect on what the answers might be than to seek for a definitive “correct” answer. The questions are designed to model the process of active reading, which is a skill with which you should already be familiar. Active reading is a crucial skill for doing well in law school, and the more adept you become at it before you come to school, the better you will do during your time here. If you would like to learn more about active reading, there will be content discussing the topic in more depth on the Legal Writer’s Toolkit site. You shouldn’t assume that these questions indicate a point of view or that they’re trying to steer you to answer them in a particular way. Rather, they’re intended to provoke you to think critically about what you read and to help you form your own conclusions, based on the information the author gives you about the topics discussed in the book. -

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The Personnel Series, consisting of approximately 17,900 pages, is comprised of three subseries, an alphabetically arranged Chiefs of Mission Subseries, an alphabetically arranged Special Liaison Staff Subseries and a Chronological Subseries. The entire series focuses on appointments and evaluations of ambassadors and other foreign service personnel and consideration of political appointees for various posts. The series is an important source of information on the staffing of foreign service posts with African- Americans, Jews, women, and individuals representing various political constituencies. Frank assessments of the performances of many chiefs of mission are found here, especially in the Chiefs of Mission Subseries and much of the series reflects input sought and obtained by Secretary Dulles from his staff concerning the political suitability of ambassadors currently serving as well as numerous potential appointees. While the emphasis is on personalities and politics, information on U.S. relations with various foreign countries can be found in this series. The Chiefs of Mission Subseries totals approximately 1,800 pages and contains candid assessments of U.S. ambassadors to certain countries, lists of chiefs of missions and indications of which ones were to be changed, biographical data, materials re controversial individuals such as John Paton Davies, Julius Holmes, Wolf Ladejinsky, Jesse Locker, William D. Pawley, and others, memoranda regarding Leonard Hall and political patronage, procedures for selecting career and political candidates for positions, discussions of “most urgent problems” for ambassadorships in certain countries, consideration of African-American appointees, comments on certain individuals’ connections to Truman Administration, and lists of personnel in Secretary of State’s office. -

Constance Baker Motley, James Meredith, and the University of Mississippi

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY, JAMES MEREDITH, AND THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Denny Chin* & Kathy Hirata Chin** INTRODUCTION In 1961, James Meredith applied for admission to the University of Mississippi. Although he was eminently qualified, he was rejected. The University had never admitted a black student, and Meredith was black.1 Represented by Constance Baker Motley and the NAACP Legal De- fense and Educational Fund (LDF), Meredith brought suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, alleging that the university had rejected him because of his race.2 Although seven years had passed since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education,3 many in the South—politicians, the media, educators, attor- neys, and even judges—refused to accept the principle that segregation in public education was unconstitutional. The litigation was difficult and hard fought. Meredith later described the case as “the last battle of the * United States Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. ** Senior Counsel, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP. 1. See Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343, 345–46 (5th Cir. 1962) (setting forth facts); Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 697–99 (5th Cir. 1962) (same). The terms “black” and “Afri- can American” were not widely used at the time the Meredith case was litigated. Although the phrase “African American” was used as early as 1782, see Jennifer Schuessler, The Term “African-American” Appears Earlier than Thought: Reporter’s Notebook, N.Y. Times: Times Insider (Apr. 21, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/04/21/ the-term-african-american-appears-earlier-than-thought-reporters-notebook/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review); Jennifer Schuessler, Use of ‘African-American’ Dates To Nation’s Earliest Days, N.Y. -

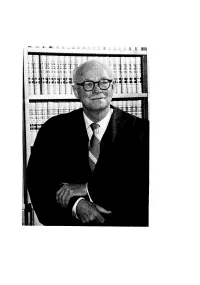

Judge William C

Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court Reception and Dinner onn . C er C I m N a N i l o l f i C W o . u N r O t H I P N e 8 w 00 York 2 January 17, 2018 The Union League Club of New York Judge William C. Conner Mission of the Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court The mission of the Hon. William C. Conner Inn of Court is to promote excellence in professionalism, ethics, civility, and legal skills for judges, lawyers, academicians, and students of law and to advance the education of the members of the Inn, the members of the bench and bar, and the public in the fields of intellectual property law. At our Inaugural Dinner in 2009, we presented Mrs. Conner with a bouquet of her favorite flowers - yellow roses. Honorable William C. Conner passed away on July 9, 2009. His wife, Janice Files Conner, passed away on September 12, 2011. We continue to commemorate Mrs. Conner every year with yellow roses on the tables at our Annual Dinner. Program Reception • 6:00 pm Dinner • 7:00 pm Presentations 2018 Conner Inn Justice Awards to Distingished Senior Judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, and U.S. District for the Southern District of New York 2018 Conner Inn Excellence Award to Hon. Pierre N. Leval Senior Circuit Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Presented by Hon. J. Paul Oetken District Judge, U.S.