1999 Blades Geoffrey Ethesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

The British Empire on the Western Front: a Transnational Study of the 62Nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4Th Division

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-09-24 The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division Jackson, Geoffrey Jackson, G. (2013). The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28020 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1036 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The British Empire on the Western Front: A Transnational Study of the 62nd West Riding Division and the Canadian 4th Division By Geoffrey Jackson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR MILITARY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER 2013 © Geoffrey Jackson 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a detailed transnational comparative analysis focusing on two military units representing notably different societies, though ones steeped in similar military and cultural traditions. This project compared and contrasted training, leadership and battlefield performance of a division from each of the British and Canadian Expeditionary Forces during the First World War. -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Limp Lavender Leather

Plum Lines The quarterly newsletter of The Wodehouse Society Vol. 2 i No. i Spring 2000 LIMP LAVENDER LEATHER By Tony Ring A talk delivered at the Houston convention of The Wodehouse Society, October 1999- Tony’s rendition of the first poem was appallingly —and appropriately—earnest. He kindly supplied, at my request, copies of poems from newspapers almost a century old for reproduction here. The newspapers were, of course, part of Tony’s vast collection of Wodehousiana. — OM Be! ender leather volume which you see before Be! you contains a hundred and fifty o f his po The past is dead, ems, and is a long way from being com Tomorrow is not born. plete. The editor o f the only collection of Be today! his poems so far published, The P a rro t, Today! which emerged from the egg in 1989, made Be with every nerve, an elementary mistake by failing to list the With every fibre, source of any of its twenty-seven offerings. With every drop of your red blood! Wodehouse contrasted writing light verse Be! with the production o f lyrics, another skill Be! which he was to demonstrate with com mendable felicity, mainly in the subsequent These lines, together with a further three decade. He helpfully explained that he pre verses whose secrets Plum Wodehouse did ferred to have a melody around which to cre not reveal, earned Rocky Todd a hundred dollars in 1916 ate his lyric, otherwise he would find himself producing money and enabled him to stay in bed until four o’clock songs with the regular metre and rhythms o f light verse. -

“Every Inch a Fighting Man”

“EVERY INCH A FIGHTING MAN:” A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE MILITARY CAREER OF A CONTROVERSIAL CANADIAN, SIR RICHARD TURNER by WILLIAM FREDERICK STEWART A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Lieutenant-General Sir Richard Ernest William Turner served Canada admirably in two wars and played an instrumental role in unifying veterans’ groups in the post-war period. His experience was unique in the Canadian Expeditionary Force; in that, it included senior command in both the combat and administrative aspects of the Canadian war effort. This thesis, based on new primary research and interpretations, revises the prevalent view of Turner. The thesis recasts five key criticisms of Turner and presents a more balanced and informed assessment of Turner. His appointments were not the result of his political affiliation but because of his courage and capability. Rather than an incompetent field commander, Turner developed from a middling combat general to an effective division commander by late 1916. -

Sauce Template

Number 79 September 2016 Commemorating Percy Jeeves by Christopher Bellew t was a solemn and thoughtful group of Society silent, reflecting on Percy Jeeves’s death and on members who converged on the cricket ground at members of our own families who had lost their CIheltenham College on July 14 to watch Gloucester lives. play Essex. It is an idyllic location, the pitch fringed Edward Cazalet’s uncle, also an Edward Cazalet, with tents, reminiscent of matches a century and was killed at the Somme while serving in the Welsh more ago. One tent, dispensing ale, had straw bales Guards. He was 22 and one of 148 Old Etonians for their customers to sit on while slaking their killed at the Somme. (My grandfather was wounded thirst. W G Grace played here in the 19th century, at the Somme; his half-brother was killed in 1917 scoring the first ever triple hundred, among other serving in the Irish Guards.) The Great War touched feats. In the 20th century, Wally Hammond set a so many families, and many of us were wearing world record that still stands, taking ten catches in a regimental ties. match by a fielder. This historic ground is kept in tip-top condition and has won more than one award in recognition of that fact. It was a privilege to be here. We had come for more than a cricket match, though. In the lunch interval a crowd of more than 100 gathered around a newly planted poplar sapling to comme- morate the death of Percy Jeeves at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. -

EAST INDIA CLUB ROLL of HONOUR Regiments the EAST INDIA CLUB WORLD WAR ONE: 1914–1919

THE EAST INDIA CLUB SOME ACCOUNT OF THOSE MEMBERS OF THE CLUB & STAFF WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN WORLD WAR ONE 1914-1919 & WORLD WAR TWO 1939-1945 THE NAMES LISTED ON THE CLUB MEMORIALS IN THE HALL DEDICATION The independent ambition of both Chairman Iain Wolsey and member David Keating to research the members and staff honoured on the Club’s memorials has resulted in this book of Remembrance. Mr Keating’s immense capacity for the necessary research along with the Chairman’s endorsement and encouragement for the project was realised through the generosity of member Nicholas and Lynne Gould. The book was received in to the Club on the occasion of a commemorative service at St James’s Church, Piccadilly in September 2014 to mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. Second World War members were researched and added in 2016 along with the appendices, which highlights some of the episodes and influences that involved our members in both conflicts. In October 2016, along with over 190 other organisations representing clubs, livery companies and the military, the club contributed a flagstone of our crest to the gardens of remembrance at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. First published in 2014 by the East India Club. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing, from the East India Club. -

City Research Online

Hunter,, F.N. (1982). Grub Street and academia : the relationship between journalism and education, 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) City Research Online Original citation: Hunter,, F.N. (1982). Grub Street and academia : the relationship between journalism and education, 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/8229/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. Grub Street and Academia: The relationship between TOTIrnalism and education,' 1880-1940, with special reference to the London University Diploma for Journalism, 1919-1939. Frederic Newlands Hunter, M.A. -

Compiled by Lillian Upton Word Or Phrase

Compiled By Lillian Upton Word or phrase Explanation Letter Date of Entry 10/- Ten shillings 04.11.1916 1d novels "Penny Dreadfuls"- a cheap ond often sensational type of novel 22.03.1915 27 Grosvenor Square Robert Fleming Hospital for Officers 27 Grosvenor Square, Belgravia, London W1 Military convalescent hospital 1914-1919 In 1914 the investment banker Robert Fleming and his wife provided an auxiliary hospital for convalescent officers at their home in Grosvenor Square. By 26.06.1918 December 1914 all 10 beds were occupied. Later, the Hospital had 14 beds and was affiliated to Queen Alexandra Military Hospital. That building was demolished and now the American Embassy occupies some of the site A cheval On horseback (French) 16.03.1916 A S Choir All Saints Choir of Bromley Common in Kent where Hills' Father was Vicar 14.06.1916 A.B.s An able seaman- an unlicensed member of the deck department of a merchant ship. An AB may work 03.02.1916 as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination of these roles A.D.C. Aide de Camp (French) A military officer acting as a confidential assistant to a senior officer 25.09.1916 A.S.C. Army Service Corps A.V.C. British Army Veterinary Corps WW1 Absolument asphixie Absolutely choaked (French) Adjutant Military Officer acting as an Admin Assistant to a Senior Officer Agincourt The Battle of Agincourt was a major English victory in the Hundred Years' War. The battle occurred 02.03.1918 on Friday, 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day), near Azincourt in northern France. -

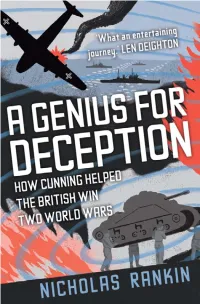

A Genius for Deception.Pdf

A Genius for Deception This page intentionally left blank A GENIUS FOR DECEPTION How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars nicholas rankin 1 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2008 by Nicholas Rankin First published in Great Britain as Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, 1914–1945 in 2008 by Faber and Faber, Ltd. First published in the United States in 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rankin, Nicholas, 1950– A genius for deception : how cunning helped the British win two world wars / Nicholas Rankin. p. cm. — (Churchill’s wizards) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-538704-9 1. Deception (Military science)—History—20th century. 2. World War, 1914–1918—Deception—Great Britain. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Deception—Great Britain. 4. Strategy—History—20th century. -

Duty and Democracy: Parliament and the First World War

DUTY AND DEMOCRACY: DUTY AND DEMOCRACY: PARLIAMENT AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR DUTY AND DEMOCRACY: PARLIAMENT AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR CHRISTOPHER BLANCHETT CHRISTOPHER DUTY AND DEMOCRACY: PARLIAMENT AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR Acknowledgements Author: Chris Blanchett Contributions from: Oonagh Gay OBE, Mari Takayanagi, Parliamentary Archives Designer: Mark Fisher, House of Commons Design Team Many thanks to the following in assisting with the production and editing of the publication: Chris Bryant MP, Marietta Crichton-Stuart, Tom Davies, Mark Fisher, James Ford, Oonagh Gay, Emma Gormley, Greg Howard, Dr Matthew Johnson, Matt Keep, Bryn Morgan, Lee Morrow, David Natzler, David Prior, Keith Simpson MP, Professor Sir Hew Strachan, Jenny Sturt, Mari Takayanagi, Melanie Unwin, Lord Wallace of Saltaire, Edward Wood. “It is by this House of Commons that the decision must be taken, and however small a minority we may be who consider that we have abandoned our attitude of neutrality too soon, every effort should still be made to do what we can to maintain our attitude of peace towards the other Powers of Europe…War is a very different thing today from what it has been before. We look forward to it with horror.” Arthur Ponsonby MP – House of Commons, 3 August 1914. Foreword Rt. Hon John Bercow MP Speaker of the House of Commons No one in the United Kingdom was During this period, important legislation immune to the horrors of the First World was passed by Parliament that had a War, whether they were at the front, in a fundamental impact on the military strategy reserved occupation, or an anxious relative of the war and wider social changes taking beset with worry on behalf of loved ones. -

War Correspondents

International Encyclopedia of the First World War War Correspondents provided by Kent Academic Repository View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Tim Luckhurst Abstract At its outbreak, newspapers in the Allied and neutral democracies hoped to present vivid descriptions of the First World War. They were soon frustrated. Censorship obstructed the adventurous style of war reporting to which readers had grown accustomed. Belligerent governments wanted journalists to encourage enlistment and maintain home front morale. Many newspapers in Britain, France and America were content to behave as patriotic propagandists. All were constrained by rules and circumstances. War correspondents downplayed misery and extolled victory. Soldiers found their behavior hard to forgive. War reporting promoted the belief that newspapers could not be trusted to tell the truth. Table of Contents 1 Introduction 2 August 1914 3 Stopping the Supply 4 Orchestrated Coverage 5 Everybody Doing Gallant Deeds 6 Censorship and Self-Censorship 7 Journalists and Propaganda 8 Conclusion 9 Notes 1. Introduction It is widely held that war correspondents produced an over-optimistic depiction of trench warfare between 1914 and 1918 and that their work distorted civilian understanding of the conflict (among the proponents of this position are Christian Delporte, Martin Farrar, Niall Ferguson, Philip Knightley and Colin Lovelace). An alternative view, namely that correspondents depicted grim realities as accurately as possible within the formal and informal constraints under which they operated, has recently earned attention. Stephen Badsey argues that British war correspondents wrote “pen-portraits of the horrors of the trenches [that] were on occasion so vivid that [Field Marshall] Haig was moved to complain”.[1] British, French and American newspaper readers in 1914 expected war reporting to be 1 of 22 International Encyclopedia of the First World War exciting and revelatory.