Download This Publication (PDF / 658.58KB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of Alcohol in the Lives of People from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue

The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview A report prepared by Sector Analysis, Ministry of Health for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand ALAC Research Monograph Series: No 2 Wellington 1997 ISSN 1174-1856 ISBN 0-477-06317-9 Acknowledgments This particular chapter which is an overview of the reports from each of the six Pacific communities would not have been possible without all the field teams and participants who took part in the project. I would like to thank Ezra Jennings-Pedro, Terrisa Taupe, Tufaina Taupe Sofaia Kamakorewa, Maikali (Mike) Kilioni, Fane Malani, Tina McNicholas, Mere Samusamuvodre, Litimai Rasiga, Tevita Rasiga, Apisa Tuiqere, Ruve Tuivoavoa, Doreen Arapai, Dahlia Naepi, Slaven Naepi, Vili Nosa, Yvette Guttenbeil, Sione Liava’a, Wailangilala Tufui , Susana Tu’inukuafe, Anne Allan-Moetaua, Helen Kapi, Terongo Tekii, Tunumafono Ken Ah Kuoi, Tali Beaton, Myra McFarland, Carmel Peteru, Damas Potoi and their communities who supported them. Many people who have not been named offered comment and shared stories with us through informal discussion. Our families and friends were drawn in and though they did not formally participate they too gave their opinions and helped to shape the information gathered. Special thanks to all the participants and Jean Mitaera, Granby Siakimotu, Kili Jefferson, Dr Ian Prior, Henry Tuia, Lita Foliaki and Tupuola Malifa who reviewed the reports and asked pertinent questions. -

Tātou O Tagata Folau. Pacific Development Through Learning Traditional Voyaging on the Waka Hourua, Haunui

Tātou o tagata folau. Pacific development through learning traditional voyaging on the waka hourua, Haunui. Raewynne Nātia Tucker 2020 School of Social Sciences and Public Policy, Faculty of Culture and Society A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... i Abstract ........................................................................................................................ v List of Figures .............................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................... vii List of Appendices ...................................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................... ix Glossary ....................................................................................................................... x Attestation of Authorship ............................................................................................. xiii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... xiv Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................ -

December 2009 TRADITIONAL Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin

Secretariat of the Pacific Community ISSN 1025-7497 Issue 26 – December 2009 TRADITIONAL Marine Resource Management and Knowledge information bulletin Editor’s note Inside this issue In this issue we have two articles. In the first, Rintaro Ono and David J. Addison examine the fishing lore of Tokelau, focusing on fishing prac- Ethnoecology and Tokelauan tices, technologies and materials, and their relationship to fish ecology. fishing lore from Atafu Atoll, They examine Tokelauan classification of the marine ecosystem and the Tokelau ethnoecology of fish and molluscs, particularly the taxonomy and ecologi- R. Ono and D.J. Addison p. 3 cal knowledge related to the behaviour of fish and other marine life. Local perceptions of sea turtles In the second, Sarah Brikke briefly examines the perception of sea turtles on Bora Bora and Maupiti islands, by French Polynesians, and in particular, the perceptions of children. This French Polynesia reminded me of a delightful afternoon session during a coral reef confer- S. Brikke p. 23 ence held in the Maldives, in March 1996. Local school pupils made a series of sophisticated presentations about what was happening to “our reefs”. Those youngsters were so refreshing that I thought such a ses- sion should be included in all technical conferences. For sure, much more research needs doing on the perceptions of young people regarding envi- ronmental and resources issues. After all, “One day all this will be yours” (and the best of luck in trying to fix all your predecessors’ messes). So it would be good to have follow-up articles from our readers on the chil- dren’s art Ms Brikke examines. -

Hold Fast to the Treasures of Tokelau; Navigating Tokelauan Agency in the Homeland and Diaspora

1 Ke Mau Ki Pale O Tokelau: Hold Fast To The Treasures of Tokelau; Navigating Tokelauan Agency In The Homeland And Diaspora A PORTFOLIO SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES AUGUST 2014 BY Lesley Kehaunani Iaukea PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE: Terence Wesley-Smith, Chairperson David Hanlon John Rosa 2 © 2014 Lesley Kehaunani Iaukea 3 We certify that we have read this portfolio and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a portfolio for the degree of Master of Arts in Pacific Islands Studies. _____________________________ Terence Wesley-Smith Chairperson ______________________________ David Hanlon ______________________________ John Rosa 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents 4 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter One: Introduction 8 1. Introduction 8 2. Positionality 11 3. Theoretical Framework 13 4. Significance 14 5. Chapter outline 15 Chapter Two: Understanding Tokelau and Her People 18 1. Tokelau and her Atolls 20 2. Story of Creation from abstract elements 21 3. Na Aho O Te Pohiha (The days of darkness) 21 4. Peopling of the Tokelau Atolls 23 5. Path of Origin 24 6. Fakaofo 25 7. Nukunonu 26 8. Atafu 26 9. Olohega 26 10. Olohega meets another fate 27 11. Western contact 30 12. Myth as Practice 31 Chapter Three: Cultural Sustainability Through an Educational Platform 33 1. Education in Tokelau 34 2. The Various Methods Used 37 3. Results and impacts achieved from this study 38 4. Learning from this experience 38 5. Moving forward 43 6. -

Pacific Islands by the University of the South Pacific Suva, Fiji ©H.E

imfcm fehk, 1 b . ,.' " * l Sm, , -.< äflj -Ff r.*^ ¥ ^ m / h i ^ r w ljt ■ ft' ■ ■ p 8fi > “*% A \ iß^jÄ . 1 "jSSm V * ■P* f 4 md ‘ 'Jt W W f l I ^ ■ V 6 ' j p w ~ i I V A U . GROUP - 10“ - 3 Q 0 o q ' Sunäav I. rPLBASS RETURN 7 _ . _......._ ■ K.ERMADEC • ' GROUP I EDiiOVJAL DEPARTMENT , Santiago y l / CHILE ( / »iM tiä yilOtiM yNiV£fiS!TV[i i Auckland i*** -I - * * »■% If* _40° \ / n e w ) 40»- RECOMMENDED RETi f l D S O ' /ZEA LA N D f PUBLICATION DATE ■H d M 180° 160° 140° 120° KK)0 80° I__ I | % Main Routes Gomez (2); Urmeneta y Ramos; Barbara 10 Guillermo: from Rapa. Notes Gomez (repatriation voyage). 11 lose Castro: from Rapa. 1 Northern Route from Callao to or through Southern route from Easter Island to Rapa, 12 Rosa Patricia: from Rapa. 1 Routes within island groups are not shown the Marquesas and Northern Cook Groups, taken by Cora (via Mangareva); Guillermo; 13 Rosa y Carmen: from Rapa. but are detailed in Table 2. taken by Adelante (1|; Jorge Zahaza; Jost Castro; Rosa Patricia; Rosa y Carmen 14 Micaela Miranda: from Rapa. 2 Voyages (route numbers) in an easterly Manualita Costas; Trujillo; Apuiimac; (via Mangareva); Micaela Miranda; Misti; 15 Ellen Elizabeth: from Tongareva. direction are underlined. Eliza Mason; Adelante (2); Genara; Barbara Gomez 16 Dolores Carolina; Polinesia; Honorio; from 3 The return route is only shown to the last Empresa; Dolores Carolina; Polinesia; (repatriation voyage). Pukapuka. island visited, from which ships are Adelante (3); General Prim (2|; Diamant Other Routes 17 La Concepcion. -

Practices of Place-Making and Belonging Among Tokelau Migrants in North Queensland

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Mobbs, Diane (2013) From a distant shore: practices of place-making and belonging among Tokelau migrants in North Queensland. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/40095/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/40095/ From a Distant Shore Practices of Place-making and Belonging among Tokelau Migrants in North Queensland From a distant shore: practices of place-making and belonging among Tokelau migrants in North Queensland. A Thesis submitted by Diane Mobbs May 2013 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology School of Arts and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Thesis network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. iii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. -

14Th AUGUST 1971 KAZIMIERZ WODZICKI, Ph

.J...) 3~ -...,. '1 z --, 'WOD R E P 0 R T ON THE SYMPOSIUM ON CONSERVATION OF NATURE REEF AND LAGOONS NOUMEA, NEW CALEDONIA, 5th - 14th AUGUST 1971 BY \ KAZIMIERZ WODZICKI, Ph.D. (KRAKOW), F.R.S.N.Z. WELLINGTON, N.Z. OCTOBER, 1971 !J!i"l"tV tleUTH PAClFJC COMMI§§J§f'l ...-- ;:!..... ·• ·c- TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Participants 2 Conservation Problems of the Territories in the South Pacific Commission Region 2 Conservation Problems of the Pacific Islands and Ways of their Solution 11 Section II - General Ecological Assessment of Pacific Islands 12 Section III - Problems of Conservation and Planning for their Solution 14 Section IV - Suggestions of Appropriate Legislation concerning Conservation 24 Section V - The Role of International Organizations 25 Section VI - Conservation Education 26 Recommendations 28 Discussion 31 Acknowledgments 35 References 36 Appendix I. List of Participants, 4 pp Appendix II. Programme of Technical Discussions, 2 pp. Appendix III. Resolutions, 12pp. REPORT ON THE SOUTH PACIFIC COMMISSION/INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE & NATURAL RESOURCES SYMPOSIUM ON CONSERVATION OF NATURE - REEF & LAGOONS HELD AT NOUMEA, NEW CALEDONIA, 5th 14th AUGUST, 1971 by Kazimierz Wodzicki, Ph.Do (Krakow), F.R.S.N.Z. New Zealand Department of Scientific & Industrial Research, Wellington. INTRODUCTION Conservation of nature in the Pacific has been the concern of practically all Pacific Science Congresses at their quinquennial meetings since their inception. However, -never--- before has a meeting been called that would be devoted to conservation problems of a single region of that vast area and that would include an overali programme attempting to cure the ills and promote a better future. -

Wayfinding in Pacific Linguascapes: Negotiating Tokelau Linguistic Identities in Hawai‘I

WAYFINDING IN PACIFIC LINGUASCAPES: NEGOTIATING TOKELAU LINGUISTIC IDENTITIES IN HAWAI‘I A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS AUGUST 2012 By Akiemi Glenn Dissertation Committee: Yuko Otsuka, Chairperson Michael Forman Katie Drager William O’Grady Richard Schmidt TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication and acknowledgments i Abstract iv List of tables and figures v Epigraph vi 1. Introduction and research questions 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Research questions 2 1.3 Tokelau linguistic identity in a transnational space 4 1.3.1 The Tokelauan language in the diaspora 9 1.3.2 Olohega in Tokelau 12 1.4 Tokelauans in Hawai'i 16 1.4.2 Te Lumanaki o Tokelau i Amelika School 18 1.4.3 Tokelau identities in Hawai'i 23 1.5 Overview of the study 25 2. Theoretical frameworks 26 2.1 Introduction 26 2.2 Theories of community 26 2.2.1 Speech communities and communities of practice 27 2.2.2 Imagined communities 29 2.3 Language and place 31 2.3.1 Multilocality and multivocality 31 2.3.2 Linguistic ecologies 33 2.4 Social meaning and metalinguistic knowledge 35 2.4.1 Performance and performativity 35 2.4.2 Indexicality 36 2.4.3 Enregisterment 37 2.4.4 Stancetaking in discourse 38 2.4.5 Crossing 40 2.4.6 Language ideology 41 2.5 Ideologies of language maintenance and endangerment 41 2.5.1 Heritage language 42 2.5.2 Language revitalization and endangerment 44 3. -

Recent Pacific Islands Publications: Selected Acquistions, June 1999

bksnoted Page 143 Thursday, June 21, 2001 2:15 PM BOOKS NOTED RECENT PACIFIC ISLANDS PUBLICATIONS: SELECTED ACQUISITIONS, JUNE 1999–FEBRUARY 2000 This list of significant new publications relating to the Pacific Islands was selected from new acquisitions lists received from Brigham Young University –Hawai‘i, University of Hawai‘i at Mânoa, Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Univer- sity of Auckland, East-West Center, University of the South Pacific, National Library of Australia, Melanesian Studies Resource Center of the University of California–San Diego, and Secretariat of the Pacific Community Library. Other libraries are invited to send contributions to the Books Noted Editor for future issues. Listings reflect the extent of information provided by each institution. Ahmed-Michaux, Paul, and William Roos. Images de la population de la Nouvelle-Calédo- nie: Principaux résultats de recensement 1996. Paris: Inst. National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, 1997. Aiu, Pua‘ala‘okalani D. This Land Is Our Land: The Social Construction of Kaho‘olawe Island. Ph.D. thesis, U. Massachusetts, 1997. Aldrich, Robert, and John Connell. The Last Colonies. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 1998. Alegado, Dean T. Sinking Roots: Filipino American Legacy in Hawaii. Honolulu: Center for Philippine Studies, U. Hawai‘i, 1998. Alexander, Joseph H. Utmost Savagery: The Three Days of Tarawa. Annapolis: Naval Inst. Press, 1995. Al Wardi, Semir. Tahiti et la France: Le partage du pouvoir. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998. Anderson, Atholl. An Ethno-history of the Southern Maori. Dunedin: U. Otago Press, 1997. Anouya, D., et al. 40 ans de poésié néo-calédonniene, 1954–1994: Anthologie. Noumea: Club des Amis de la Poésié, 1994. -

Tokelau Programme Evaluation Evaluation Report

December 2015 New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade | Manatū Aorere Evaluation of the Tokelau Country Programme Evaluation of the Tokelau Country Programme Mathea Roorda, David Carpenter, Andrew Laing and Mark McGillivray December 2015 Acknowledgments A sincere thank you to all those in Tokelau, Apia and New Zealand who participated in the evaluation. Thank you for sharing your experiences, perspectives and your vision for Tokelau. Thank you to the three village Taupulega and members of the Tokelau Council for their support and active participation during the evaluation. For logistical support in preparing for, and helping to conduct, the interviews in Apia and on each atoll, thank you to Margaret Sapolu, Hina Kele, Aukusitino Vitale and Ivoni Taumanu. 1 Further details about author Mathea Roorda is an experienced evaluation professional from New Zealand with significant experience managing and conducting multimethod research and evaluation projects. David Carpenter is Principal Adviser in Evaluation and Research at the Asia-Pacific office of Adam Smith International in Sydney, Australia. Andrew Laing is Public Financial Management Lead, Afghanistan and Public Economics Practice Manager for the Institute for State Effectiveness (ISE).Mark McGillivray is Research Professor of International Development at the Alfred Deakin Institute of Deakin University in Geelong, Australia. Adam Smith International (ASI) is an award-winning professional services business that delivers real impact, value and lasting change through projects supporting economic growth and government reform internationally. Our reputation as a global leader has been built on the positive results our projects have achieved in many of the world’s most challenging environments. We provide high quality specialist expertise and intelligent programme management capability at all stages of the project cycle, from policy and strategy development, to design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. -

Cultural Practices & Protocols

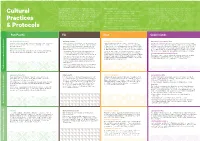

Engagement that is meaningful is about respecting Advice may be about: By having a general understanding and knowing how to behave in these cultural practices and protocols. Pacific values common to • Formal ceremonies and knowing who and how to address situations shows Pacific communities respect and is a step in the right Cultural all Pacific Islands should always be considered when observing people and their roles in the appropriate manner direction for building good relationships. Below are a few examples any customs. However, among the different islands there are which demonstrate how practices vary from island to island. This is by • Use of island languages and translation by non-English speakers distinct differences in cultural practices, roles of family no means an exhaustive list but is merely intended to give you a basic Practices members, traditional dress and power structures. • Acknowledging and allowing time for elders to contribute introduction only. If you somehow forget everything you read here, • Taking time to observe protocols which uphold spirituality just remember to act respectfully and that it’s okay to ask if you don’t If you’re asked to attend a Pacific event or ceremony, through prayers. understand. it’s anticipated that you be accompanied and/or advised & Protocols by Pacific peoples who can help guide you. Note - A full list of basic greetings can be found at www.mpp.govt.nz - Tonga, Fiji and Samoa are the only Pacific countries that are commonly known for kava ceremony practices. Pan-Pacific Fiji Niue Cook Islands Role of spirituality in meetings Welcoming ceremony Welcoming ceremony and dance Haircutting ceremony (pakoti rouru) Pacific meetings or events usually begin and close with a prayer, and food is blessed Veiqaravi vakavanua is the traditional way to welcome an honoured guest Takalo was traditionally performed before going to war. -

A Review of New Zealand Policy Toward the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Kiribati and Tuvalu

New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours: A Review of New Zealand Policy Toward the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Kiribati and Tuvalu I.G. Bertram and R.F. Watters INSTITUTE OF POLICY STUDIES WORKING PAPER 84/01 October 1984 INSTITUTE OF POLICY New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours: A STUDIES WORKING Review of New Zealand Policy Toward the Cook PAPER Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Kiribati and Tuvalu 84/01 MONTH/YEAR October 1984 AUTHORS I.G. Bertram and R.F. Watters [email protected] [email protected] ACKNOWLE- DGEMENTS School of Government INSTITUTE OF POLICY Victoria University of Wellington STUDIES Level 5 Railway Station Building Bunny Street Wellington NEW ZEALAND PO Box 600 Wellington NEW ZEALAND Email: [email protected] Phone: + 64 4 463 5307 Fax: + 64 4 463 7413 Website www.ips.ac.nz The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or DISCLAIMER recommendations expressed in this Working Paper are strictly those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute of Policy Studies, the School of Government or Victoria University of Wellington. The aforementioned take no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in these working papers. The paper is presented not as policy, but with a view to inform and stimulate wider debate. New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours: A Review of New Zealand Policy Toward the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Kiribati and Tuvalu In 1984 the Ministry of Foreign affairs and trade commissioned the Institute of Policy Studies to conduct a wide-ranging review of New Zealand policy in the South Pacific.