Wayfinding in Pacific Linguascapes: Negotiating Tokelau Linguistic Identities in Hawai‘I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emerging New Zealand Jurisprudence on Climate Change, Disasters and Displacement

MIGRATION STUDIES VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 2015 131–142 131 The emerging New Zealand jurisprudence on climate change, disasters and displacement Jane McAdamà *Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, NSW 2052, Australia. Email: [email protected] Abstract Downloaded from In mid-2014, there was global media coverage of a decision by the New Zealand Immigration and Protection Tribunal, heralded as the first legal recognition of ‘climate change refugees’. Despite the hype, the Tribunal had made no such finding. The case concerned a family of four from the small Pacific island State of Tuvalu, who argued, http://migration.oxfordjournals.org/ among other things, that the effects of climate change—in particular, a lack of fresh drinking water and sea-level rise—would have adverse impacts on them if they were forced to return home. While the Tribunal ultimately permitted them to stay in New Zealand, this was not because of the impacts of climate change in Tuvalu, but rather because of their strong family ties within New Zealand. The decision was based purely on humanitarian and discretionary grounds, not on any domestic or international legal obligation. However, since 2013, New Zealand has started to specifically and systematically delineate the legal protection framework applicable to claims based on the impacts of climate change, natural disasters or environmental degradation. While no one has by guest on March 10, 2015 yet been granted protection on these grounds, New Zealand’s jurisprudence provides the most comprehensive analysis by decision-makers to date about the scope and content of protection for people escaping the impacts of climate change and disasters. -

Ethnography of Ontong Java and Tasman Islands with Remarks Re: the Marqueen and Abgarris Islands

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 9, No. 3 July 1986 ETHNOGRAPHY OF ONTONG JAVA AND TASMAN ISLANDS WITH REMARKS RE: THE MARQUEEN AND ABGARRIS ISLANDS by R. Parkinson Translated by Rose S. Hartmann, M.D. Introduced and Annotated by Richard Feinberg Kent State University INTRODUCTION The Polynesian outliers for years have held a special place in Oceanic studies. They have figured prominently in discussions of Polynesian set- tlement from Thilenius (1902), Churchill (1911), and Rivers (1914) to Bayard (1976) and Kirch and Yen (1982). Scattered strategically through territory generally regarded as either Melanesian or Microne- sian, they illustrate to varying degrees a merging of elements from the three great Oceanic culture areas—thus potentially illuminating pro- cesses of cultural diffusion. And as small bits of land, remote from urban and administrative centers, they have only relatively recently experienced the sustained European contact that many decades earlier wreaked havoc with most islands of the “Polynesian Triangle.” The last of these characteristics has made the outliers particularly attractive to scholars interested in glimpsing Polynesian cultures and societies that have been but minimally influenced by Western ideas and Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 1 2 Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 accoutrements. For example, Tikopia and Anuta in the eastern Solo- mons are exceptional in having maintained their traditional social structures, including their hereditary chieftainships, almost entirely intact. And Papua New Guinea’s three Polynesian outliers—Nukuria, Nukumanu, and Takuu—may be the only Polynesian islands that still systematically prohibit Christian missionary activities while proudly maintaining important elements of their old religions. -

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Lead Authors:∗ Tamara Gurevich and Peter Herman Contributing Authors: Nabil Abbyad, Meryem Demirkaya, Austin Drenski, Jeffrey Horowitz, and Grace Kenneally Version 1.00 Abstract This document provides technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset. The Dynamic Gravity dataset provides extensive country and country pair information for a total of 285 countries and territories, annually, between the years 1948 to 2016. This documentation extensively describes the methodology used for the creation of each variable and the information sources they are based on. Additionally, it provides a large collection of summary statistics to aid in the understanding of the resulting Dynamic Gravity dataset. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional devel- opment of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected] or [email protected]. ∗We thank Renato Barreda, Fernando Gracia, Nuhami Mandefro, and Richard Nugent for research assistance in completion of this project. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Nomenclature . .3 1.2 Variables Included in the Dataset . .3 1.3 Contents of the Documentation . .6 2 Country or Territory and Year Identifiers 6 2.1 Record Identifiers . -

Sustained Prehistoric Exploitation of a Marshall Islands Fishery

Sustained prehistoric exploitation of a Marshall Islands fishery: ichthyoarchaeological approaches, marine resource use, and human- environment interactions on Ebon Atoll Ariana Blaney Joan Lambrides BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Social Science Abstract Atolls are often characterised in terms of the environmental constraints and challenges these landscapes impose on sustained habitation, including: nutrient-poor soils and salt laden winds that impede plant growth, lack of perennial surface fresh water, limited terrestrial biodiversity, and vulnerability to extreme weather events and inundation since most atolls are only 2-3 m above sea level. Yet, on Ebon Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands in eastern Micronesia, the oceanside and lagoonside intertidal marine environments are expansive, with the reef area four times larger than the land area, supporting a diverse range of taxa. Given the importance of finfish resources in the Pacific, and specifically Ebon, this provided an ideal context for evaluating methods and methodological approaches for conducting Pacific ichthyoarchaeological analyses, and based on this assessment, implement high resolution and globally recognised approaches to investigate the spatial and temporal variation in the Ebon marine fishery. Variability in landscape use, alterations in the range of taxa captured, archaeological proxies of past climate stability, and the comparability of archaeological and ecological datasets were considered. Utilising a historical ecology approach, this thesis provides an analysis of the exploitation of the Ebon marine fishery from initial settlement to the historic period—two millennia of continuous occupation. The thesis demonstrated the importance of implementing high resolution methods and methodologies when considering long-term human interactions with marine fisheries. -

The Place of Alcohol in the Lives of People from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue

The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview The place of alcohol in the lives of people from Tokelau, Fiji, Niue, Tonga, Cook Islands and Samoa living in New Zealand: an overview A report prepared by Sector Analysis, Ministry of Health for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand ALAC Research Monograph Series: No 2 Wellington 1997 ISSN 1174-1856 ISBN 0-477-06317-9 Acknowledgments This particular chapter which is an overview of the reports from each of the six Pacific communities would not have been possible without all the field teams and participants who took part in the project. I would like to thank Ezra Jennings-Pedro, Terrisa Taupe, Tufaina Taupe Sofaia Kamakorewa, Maikali (Mike) Kilioni, Fane Malani, Tina McNicholas, Mere Samusamuvodre, Litimai Rasiga, Tevita Rasiga, Apisa Tuiqere, Ruve Tuivoavoa, Doreen Arapai, Dahlia Naepi, Slaven Naepi, Vili Nosa, Yvette Guttenbeil, Sione Liava’a, Wailangilala Tufui , Susana Tu’inukuafe, Anne Allan-Moetaua, Helen Kapi, Terongo Tekii, Tunumafono Ken Ah Kuoi, Tali Beaton, Myra McFarland, Carmel Peteru, Damas Potoi and their communities who supported them. Many people who have not been named offered comment and shared stories with us through informal discussion. Our families and friends were drawn in and though they did not formally participate they too gave their opinions and helped to shape the information gathered. Special thanks to all the participants and Jean Mitaera, Granby Siakimotu, Kili Jefferson, Dr Ian Prior, Henry Tuia, Lita Foliaki and Tupuola Malifa who reviewed the reports and asked pertinent questions. -

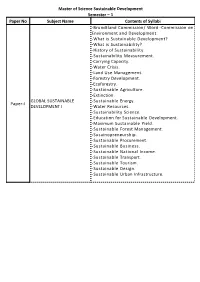

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper

Master of Science Sustainable Development Semester – 1 Paper No Subject Name Contents of Syllabi -Brundtland Commission/ Word -Commission on Environment and Development. -What is Sustainable Development? -What is Sustainability? -History of Sustainability. -Sustainability Measurement. -Carrying Capacity. -Water Crisis. -Land Use Management. -Forestry Development. -Ecoforestry. -Sustainable Agriculture. -Extinction. GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE -Sustainable Energy. Paper-I DEVELOPMENT I -Water Resources. -Sustainability Science. -Education for Sustainable Development. -Maximum Sustainable Yield. -Sustainable Forest Management. -Susainopreneurship. -Sustainable Procurement. -Sustainable Business. -Sustainable National Income. -Sustainable Transport. -Sustainable Tourism. -Sustainable Design. -Sustainable Urban Infrastructure. Master of Science Sustainable Development -What is Biodiversity? -Measurement of Biodiversity. -Species Richness. -Shannon Index. -2010 Biodiversity Indicators- Partnership. -Evolution. -Evolutionary Thought. -How does Evolution Occur? -Timeline of Evolution. BIODIVERSITY -Social Effect of Evolutionary Theory. Paper-II CONSERVATION & -Objections of Evolution. MANAGEMENT I -Population Genetics. -Genetics. -Heredity. -Mutation. -Molecular Evolution. -Genetic Recombination. -Sexual Reproduction. -Gene Flow. -Hybrid. -What is Energy? -History of Energy. -Timeline of Thermodynamics. -Units of Energy. -Potential Energy. -Elastic Energy. -Kinetic Energy. -Internal Energy. -Electromagnetism. -Electricity. GLOBAL ENERGY POLICIES Paper-III -

Tokelau the Last Colony?

Tokelau The last colony? TONY ANGELO (Taupulega) is, and long has been, the governing body. The chairman (Faipule) of the council and a village head ITUATED WELL NORTH OF NEW ZEALAND and (Pulenuku) are elected by universal suffrage in the village SWestern Samoa and close to the equator, the small every three years. The three councils send representatives atolls of Tokelau, with their combined population of about to form the General Fono which is the Tokelau national 1600 people, may well be the last colony of New Zealand. authority; it originally met only once or twice a year and Whether, when and in what way that colonial status of advised the New Zealand Government of Tokelau's Tokelau will end, is a mat- wishes. ter of considerable specula- The General Fono fre- lion. quently repeated advice, r - Kirlb•ll ·::- (Gifb•rr I•) The recently passed lbn•b'a ' ......... both to the New Zealand (Oc: ..n I} Tokelau Amendment Act . :_.. PMtnb 11 Government and to the UN 1996- it received the royal Committee on Decoloni • •• roltfl•u assent on 10 June 1996, and 0/tlh.g• sation, that Tokelau did not 1- •, Aotum•- Uu.t (Sw•ln•J · came into force on 1 August 1 f .. • Tllloplol ~~~~~ !•J.. ·-~~~oa wish to change its status ~ ~ 1996 - is but one piece in ' \, vis-a-vis New Zealand. the colourful mosaic of •l . However, in an unexpected Tokelau's constitutional de change of position (stimu- velopment. lated no doubt by external The colonialism that factors such as the UN pro Tokelau has known has posal to complete its been the British version, and decolonisation business by it has lasted so far for little the year 2000), the Ulu of over a century. -

2011 Tuvalu and Tokelau Drought

2011 Tokelau and Tuvalu Drought Response LTCOL Terry McDonald Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers New Zealand Defence Force Presentation Scope • Background and challenges • Deployment overview - OP Pacific Drought 2011 • Key focus areas: • “Humanitarian Assistance as a system of systems” • “Unpacking the problem” • “Information in a vacuum” • Conclusion Background and Challenges • Slow developing situation • Increasing development increases water use • Impact of La Nina on preceding six months rainfall • Reliance on rainwater capture and RO • Geographic Isolation – airfields / ports • Mission duration and footprint • NZDF MFRO capability Deployment overview – OP Pacific Drought 2011 Key Events Timeline: 28 Sep 11 – Tuvalu declares a state of emergency Sep 11 – Tokelau declares a state of emergency 30 Sep 11 – NZDF activates condition white OP Pacific Drought 04 Oct 11 – NZDF activates condition red OP Pacific Drought 05 Oct 11 – NZDF team TOKELAU deploys to AMERICAN SAMOA 06 Oct 11 – NZDF team TOKELAU links up with USCG WALNUT 07 Oct 11 – NZDF team TUVALU deploys to SAMOA 07 Oct 11 – Relief team TOKELAU arrives TOKELAU 08 Oct 11 – Relief team TUVALU arrives TUVALU 10 Oct 11 – Relief team TOKELAU RTNZ via AMERICAN SAMOA 09 Nov 11 – Relief team TUVLAU RTNZ via SAMOA Key Outcomes: TOKELAU – 123,000L of water produced and delivered to three atolls Distribution amount based on population TUVALU - 798,480L of water produced by NZDF MFRO Distribution primarily on Funafuti with Red Cross RO supporting NUKULAELAE References: http://www.tokelau.org.nz/site/tokelau/files/final%20final%20final%20tevakai%20NC.pdf -

KAY, Paul, and Chad K. Mcdaniel, the Linguistic Significance of the Meanings of Basic Color Language,Terms

7 8 Cecil H. Brown KAY, Paul, and Chad K. McDANIEL, The Linguistic Significance of the Meanings of Basic Color Language,Terms. 54:610-46. KEMPTON, Willett, 1978. Category Grading and Taxonomic Relations: a Mug Is a Sort ofAmerican Cup. Ethnologist, 5:44-65. ----------- , 1981. The Folk Classification of Ceramics: a Study of Cognitive Prototypes. New York, Academic Press. LAKOFF, George, 1987.Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about theChicago Mind. University Press. RANDALL, Robert A., 1977. Change and Variation in Samal Fishing: Making Plans to “Make a Living” in the Southern Philippines. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. ----------- , and Eugene S. HUNN, 1984. Do Life-forms Evolve or do Uses for Life? Some Doubts about Brown’s Universals Hypotheses.American Ethnologist, 11:329-49. ROSCH, Eleanor, 1975. Universals and Cultural Specifics in Human Categorization, in R.W. Brislin, S. Bochner, and W.J. Lonner (eds),Cross-cultural Perspectives on Learning: the Interface between Culture and Learning. New York, Halsted Press, pp. 177-206. ----------- , 1977. Human Categorization, in N. Warren (ed.),Studies in Cross-cultural Psychology, vol.l. New York, Academic Press, pp. 1-49. ----------- , and Carolyn B. MERVIS, 1975. Family Resemblances: Studies in the Internal Structure of Categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7:573-605. WIERZBICKA, Anna, 1985.Lexicography and Conceptual Analysis. Ann Arbor, Karoma. WITKOWSKI, Stanley R., Cecil H. BROWN, and P. CHASE, 1981. Where do Tree Terms Come from?Man, (n.s.) 16:1-14. FINGOTA/FANGOTA: SHELLFISH AND FISHING IN POLYNESIA Ross Clark University of Auckland A few years ago, in the course of a brief foray into the shallows of marine ethnotaxonomy (Clark 1981),11 suggested the possibility of “shellfish” as a labelled life-form category in some Polynesian languages. -

British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands Clive Petrovic, Esther Georges and Nancy Woodfield Andy McGowan Great Tobago General introduction The British Virgin Islands comprise more than 60 islands, and the Virgin Islands. These include the globally cays and rocks, with a total land area of approximately 58 threatened Cordia rupicola (CR), Maytenus cymosa (EN) and square miles (150 square km). This archipelago is located Acacia anegadensis (CR). on the Puerto Rican Bank in the north-east Caribbean at A quarter of the 24 reptiles and amphibians identified are approximately 18˚N and 64˚W. The islands once formed a endemic, including the Anegada Rock Iguana Cyclura continuous land mass with the US Virgin Islands and pinguis (CR), which is now restricted to Anegada. Other Puerto Rico, and were isolated only in relatively recent endemics include Anolis ernestwilliamsii, Eleutherodactylus geologic time. With the exception of the limestone island of schwartzi, the Anegada Ground Snake Alsophis portoricensis Anegada, the islands are volcanic in origin and are mostly anegadae, the Virgin Gorda Gecko Sphaerodactylus steep-sided with rugged topographic features and little flat parthenopian, the Virgin Gorda Worm Snake Typlops richardi land, surrounded by coral reefs. naugus, and the Anegada Worm Snake Typlops richardi Situated at the eastern end of the Greater Antilles chain, the catapontus. Other globally threatened reptiles within the islands experience a dry sub-tropical climate dominated by BVI include the Anolis roosevelti (CR) and Epicrates monensis the prevailing north-east trade winds. Maximum summer granti (EN). temperatures reach 31˚C; minimum winter temperatures Habitat alteration during the plantation era and the are 19˚C, and there is an average rainfall of 700 mm per introduction of invasive alien species has had major year with seasonal hurricane events. -

December 2009 TRADITIONAL Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin

Secretariat of the Pacific Community ISSN 1025-7497 Issue 26 – December 2009 TRADITIONAL Marine Resource Management and Knowledge information bulletin Editor’s note Inside this issue In this issue we have two articles. In the first, Rintaro Ono and David J. Addison examine the fishing lore of Tokelau, focusing on fishing prac- Ethnoecology and Tokelauan tices, technologies and materials, and their relationship to fish ecology. fishing lore from Atafu Atoll, They examine Tokelauan classification of the marine ecosystem and the Tokelau ethnoecology of fish and molluscs, particularly the taxonomy and ecologi- R. Ono and D.J. Addison p. 3 cal knowledge related to the behaviour of fish and other marine life. Local perceptions of sea turtles In the second, Sarah Brikke briefly examines the perception of sea turtles on Bora Bora and Maupiti islands, by French Polynesians, and in particular, the perceptions of children. This French Polynesia reminded me of a delightful afternoon session during a coral reef confer- S. Brikke p. 23 ence held in the Maldives, in March 1996. Local school pupils made a series of sophisticated presentations about what was happening to “our reefs”. Those youngsters were so refreshing that I thought such a ses- sion should be included in all technical conferences. For sure, much more research needs doing on the perceptions of young people regarding envi- ronmental and resources issues. After all, “One day all this will be yours” (and the best of luck in trying to fix all your predecessors’ messes). So it would be good to have follow-up articles from our readers on the chil- dren’s art Ms Brikke examines. -

Marshall Islands

Country Guide to Gamefishing in the Western and Central Pacific by Wade Whitelaw Oceanic Fisheries Programme Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2001 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2001 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. The SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this mate- rial for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided the SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the docu- ment and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Whitelaw, Wade Country guide to gamefishing in the Western and Central Pacific: by Wade Whitelaw 1. Fishing - Oceania. 1. Title 2. Secretariat of the Pacific Community 799.1665 AACR2 ISBN 982–203–817–8 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BP D5 98848 Noumea Cedex New Caledonia Telephone: + 687 26 20 00 Facsimile: + 687 26 38 18 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.spc.int/ Funded by AusAID Layout: Muriel Borderie Prepared for publication and printed at Secretariat of the Pacific Community headquarters Noumea, New Caledonia, 2001 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . .1 BACKGROUND . .2 SOURCES OF INFORMATION . .4 RESULTS . .4 WORLD RECORDS . .5 SEASONALITY OF GAMEFISH SPECIES . .5 SEASONALITY OF TOURISM . .5 SUMMARY OF INFORMATION BY COUNTRY . .6 American Samoa . .7 Cook Islands . .11 Federated States of Micronesia . .15 Fiji Islands . .19 French Polynesia . .23 Guam . .27 Kiribati . .31 Marshall Islands .