Stationary Bandits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Calcare Di Base” Formations from Caltanissetta (Sicily) and Rossano (Calabria) Basins: a Detailed Geochemical, Sedimentological and Bio-Cyclostratigraphical Study

EGU2020-19511 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-19511 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. New insights of Tripoli and “Calcare di Base” Formations from Caltanissetta (Sicily) and Rossano (Calabria) Basins: a detailed geochemical, sedimentological and bio-cyclostratigraphical study. Athina Tzevahirtzian1, Marie-Madeleine Blanc-Valleron2, Jean-Marie Rouchy2, and Antonio Caruso1 1Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra e del Mare (DiSTeM), Università degli Studi di Palermo, via Archirafi 20-22, 90123 Palermo, Italy 2CR2P, UMR 7207, Sorbonne Universités-MNHN, CNRS, UMPC-Paris 6, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, 57 rue Cuvier, Paris, France A detailed biostratigraphical and cyclostratigraphical study provided the opportunity of cycle-by- cycle correlations between sections from the marginal and deep areas of the Caltanissetta Basin (Sicily), and the northern Calabrian Rossano Basin. All the sections were compared with the Falconara-Gibliscemi composite section. We present new mineralogical and geochemical data on the transition from Tripoli to Calcare di Base (CdB), based on the study of several field sections. The outcrops display good record of the paleoceanographical changes that affected the Mediterranean Sea during the transition from slightly restricted conditions to the onset of the Mediterranean Salinity Crisis (MSC). This approach permitted to better constrain depositional conditions and highlighted a new palaeogeographical pattern characterized -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

Trapani Palermo Agrigento Caltanissetta Messina Enna

4 A Sicilian Journey 22 TRAPANI 54 PALERMO 86 AGRIGENTO 108 CALTANISSETTA 122 MESSINA 158 ENNA 186 CATANIA 224 RAGUSA 246 SIRACUSA 270 Directory 271 Index III PALERMO Panelle 62 Panelle Involtini di spaghettini 64 Spaghetti rolls Maltagliati con l'aggrassatu 68 Maltagliati with aggrassatu sauce Pasta cone le sarde 74 Pasta with sardines Cannoli 76 Cannoli A quarter of the Sicilian population reside in the Opposite page: province of Palermo, along the northwest coast of Palermo's diverse landscape comprises dramatic Sicily. The capital city is Palermo, with over 800,000 coastlines and craggy inhabitants, and other notable townships include mountains, both of which contribute to the abundant Monreale, Cefalù, and Bagheria. It is also home to the range of produce that can Parco Naturale delle Madonie, the regional natural be found in the area. park of the Madonie Mountains, with some of Sicily’s highest peaks. The park is the source of many wonderful food products, such as a cheese called the Madonie Provola, a unique bean called the fasola badda (badda bean), and manna, a natural sweetener that is extracted from ash trees. The diversity from the sea to the mountains and the culture of a unique city, Palermo, contribute to a synthesis of the products and the history, of sweet and savoury, of noble and peasant. The skyline of Palermo is outlined with memories of the Saracen presence. Even though the churches were converted by the conquering Normans, many of the Arab domes and arches remain. Beyond architecture, the table of today is still very much influenced by its early inhabitants. -

Orari E Sedi Dei Centri Di Vaccinazione Dell'asp Di Caltanissetta

ELENCO CENTRI DI VACCINAZIONE ASP CALTANISSETTA Presidio Altro personale che Giorni e orario di ricevimento Recapito e-mail * Medici Infermieri Comune ( collabora al pubblico Cammarata Giuseppe Bellavia M. Rosa L-M -M -G-V h 8.30-12.30 Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. C 0934 506136/137 [email protected] Petix Vincenza ar er Russo Sergio Scuderi Alfia L e G h 15.00-16.30 previo appuntamento L-Mar-Mer-G-V h 8.30-12.30 Milisenna Rosanna Modica Antonina Caltanissetta Via Cusmano 1 pad. B 0934 506135/009 [email protected] Diforti Maria L e G h 15.00 - 16.30 Giugno Sara Iurlaro Maria Antonia Sedute vaccinali per gli adolescenti organizzate previo appuntamento Delia Via S.Pertini 5 0922 826149 [email protected] Virone Mario Rinallo Gioacchino // Lunedì e Mercoledì h 9 -12.00 Sanfilippo Salvatore Sommatino Via A.Moro 76 0922 871833 [email protected] // // Lunedì e Venerdì h 9.00 -12.00 Castellano Paolina L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Resuttano Via Circonvallazione 4 0934 673464 [email protected] Accurso Vincenzo Gangi Maria Rita // Previo appuntamento S.Caterina Accurso Vincenzo Fasciano Rosamaria M V h 9.00-12.00 Via Risorgimento 2 0934 671555 [email protected] // ar - Villarmosa Severino Aldo Vincenti Maria L e G ore p.m. previo appuntamento Martedì e Giovedì h 9.00-12.00 Riesi C/da Cicione 0934 923207 [email protected] Drogo Fulvio Di Tavi Gaetano Costanza Giovanna L - G p.m. -

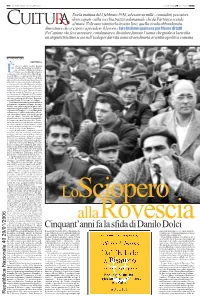

Cinquant'anni Fa La Sfida Di Danilo Dolci

40 LA DOMENICA DI REPUBBLICA DOMENICA 29 GENNAIO 2006 Era la mattina del 2 febbraio 1956, ed erano in mille - contadini, pescatori, disoccupati - sulla vecchia trazzera demaniale che da Partinico scende al mare. Volevano rimetterla in sesto loro, quella strada abbandonata, dimostrare che ci si poteva prendere il lavoro e fare insieme qualcosa per il bene di tutti. Fu l’azione che fece arrestare, condannare e diventare famoso l’uomo che guidava la rivolta: un utopista triestino sceso nell’isola per dar vita a una straordinaria avventura politica e umana ATTILIO BOLZONI PARTINICO ancora senza nome questa strada che dal paese scende fi- no al mare. Ripida nel primo Ètratto, poi va giù dolcemente con le sue curve che sfiorano alberi di pe- sco e di albicocco, passa sotto due ponti, scavalca la ferrovia. L’hanno asfaltata appena una decina di anni fa, prima era un sentiero, una delle tante regie trazze- re borboniche che attraversano la cam- pagna siciliana. È lunga otto chilometri, un giorno forse la chiameranno via dello Sciopero alla Rovescia. Siamo sul ciglio di questa strada di Partinico mezzo se- colo dopo quel 2 febbraio del ‘56, la stia- mo percorrendo sulle tracce di un uomo che sapeva inventare il futuro. Era un ir- regolare Danilo Dolci, uno di confine. Quella mattina erano quasi in mille qui sul sentiero e in mezzo al fango, inverno freddo, era caduta anche la neve sullo spuntone tagliente dello Jato. I pescatori venivano da Trappeto e i contadini dalle valli intorno, c’erano sindacalisti, alleva- tori, tanti disoccupati. E in fondo quegli altri, gli «sbirri» mandati da Palermo, pronti a caricare e a portarseli via quelli lì. -

Elenco Medici Di Medicina Generale – Ambito Di Caltanissetta

Foglio1 Elenco Medici di Medicina Generale – Ambito di Caltanissetta Cod Reg. Cognome e Nome Indirizzo ambulatorio tel./cell E-MAIL PEC 504762 Alaimo Giovanna Maria Via Lazio 19 Caltanissetta 0934551232/3398212716 [email protected] [email protected] 506315 Alessandro Salvatore M. Via E. De Nicola 6 Caltanissetta 0934595482 3389145433 [email protected] [email protected] 506235 Arnone Marco Via T. Bennardo 29 Caltanissetta 093429800 3387673597 marco [email protected] [email protected] 506849 Baio Mazzola Carlo M. Via G.Tomasi di Lampedusa 1 Caltanissetta 3894887672 [email protected] [email protected] 503781 Bennici Calogero Via G. Matteotti 37 Sommatino 0922871305/3293835165 [email protected] [email protected] 506598 Bevilacqua Calogera Viale Sicilia 91 Caltanissetta 0934598786/3288370178 [email protected] [email protected] 505071 Boscaglia Vincenzo Via Kennedy 16 Caltanissetta 093427578/3290071467 [email protected] [email protected] 506850 Burgio Carmela Via Capitano D'antona 46 Riesi 0922730536/3382439690 [email protected] 50705/6 Cammarata Rocco Via Leonardo da Vinci snc Caltanissetta 330.846755- -0934575489 [email protected] 504250 Capraro Pio Felice Via Calafato 68 c Caltanissetta 093426609/3498518596 [email protected] [email protected] 504261 Carbone Giuseppe Viale Trieste 132 Caltanissetta 0934599211 [email protected] [email protected] 500645 Carvello Angelo Via G. Pagliarello 131 Delia 0922820795/3387223293 [email protected] [email protected] 507000 Castellano Paolina Via Leonardo Da Vinci n.26 Caltanissetta 3298130768 [email protected] [email protected] 506918 Condemi Carmelo Via Circonvallazione n. -

20Th Century Communism 16.Indd

The University of Manchester Research Book Review: Second World, Second Sex. Socialist Women’s Activism and Global Solidarity during the Cold War Document Version Final published version Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Müller, T. R. (2019). Book Review: Second World, Second Sex. Socialist Women’s Activism and Global Solidarity during the Cold War. Twentieth Century Communism, (16), 150-154. Published in: Twentieth Century Communism Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 The Communist Party of Cyprus, the Comintern and the uprising of 1931 125 Reviews Richard J Evans; Eric Hobsbawm: a Life in History (London: Little, Brown; 2019), 1408707411, 785pp Biographical advantages This is truly a monumental biography, well deserving of its subject. At nearly 800 pages, eight-one of them endnotes, it is not likely to be superseded anytime in the near future. -

Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: the Market for Lemons

_____________________________________________________________________ CREDIT Research Paper No. 12/01 _____________________________________________________________________ Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons by Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, Ola Olsson Abstract Since its first appearance in the late 1800s, the origins of the Sicilian mafia have remained a largely unresolved mystery. Both institutional and historical explanations have been proposed in the literature through the years. In this paper, we develop an argument for a market structure-hypothesis, contending that mafia arose in towns where firms made unusually high profits due to imperfect competition. We identify the market for citrus fruits as a sector with very high international demand as well as substantial fixed costs that acted as a barrier to entry in many places and secured high profits in others. We argue that the mafia arose out of the need to protect citrus production from predation by thieves. Using the original data from a parliamentary inquiry in 1881-86 on all towns in Sicily, we show that mafia presence is strongly related to the production of orange and lemon. This result contrasts recent work that emphasizes the importance of land reforms and a broadening of property rights as the main reason for the emergence of mafia protection. JEL Classification: Keywords: mafia, Sicily, protection, barrier to entry, dominant position _____________________________________________________________________ Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade, University of Nottingham _____________________________________________________________________ CREDIT Research Paper No. 12/01 Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons by Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, Ola Olsson Outline 1. Introduction 2. Background and Literature Review 3. The Model 4. -

Società E Cultura 65

Società e Cultura Collana promossa dalla Fondazione di studi storici “Filippo Turati” diretta da Maurizio Degl’Innocenti 65 1 Manica.indd 1 19-11-2010 12:16:48 2 Manica.indd 2 19-11-2010 12:16:48 Giustina Manica 3 Manica.indd 3 19-11-2010 12:16:53 Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al contributo di fondi di ricerca del Dipartimento di studi sullo stato dell’Università de- gli Studi di Firenze. © Piero Lacaita Editore - Manduria-Bari-Roma - 2010 Sede legale: Manduria - Vico degli Albanesi, 4 - Tel.-Fax 099/9711124 www.lacaita.com - [email protected] 4 Manica.indd 4 19-11-2010 12:16:54 La mafia non è affatto invincibile; è un fatto uma- no e come tutti i fatti umani ha un inizio e avrà anche una fine. Piuttosto, bisogna rendersi conto che è un fe- nomeno terribilmente serio e molto grave; e che si può vincere non pretendendo l’eroismo da inermi cittadini, ma impegnando in questa battaglia tutte le forze mi- gliori delle istituzioni. Giovanni Falcone La lotta alla mafia deve essere innanzitutto un mo- vimento culturale che abitui tutti a sentire la bellezza del fresco profumo della libertà che si oppone al puzzo del compromesso, dell’indifferenza, della contiguità e quindi della complicità… Paolo Borsellino 5 Manica.indd 5 19-11-2010 12:16:54 6 Manica.indd 6 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Alla mia famiglia 7 Manica.indd 7 19-11-2010 12:16:54 Leggenda Archivio centrale dello stato: Acs Archivio di stato di Palermo: Asp Public record office, Foreign office: Pro, Fo Gabinetto prefettura: Gab. -

CATTOLICI, CHIESA E MAFIA Aspetti Storici, Politici E Religiosi Convegno Di Studi (Università Di Messina, 27-29 Novembre 2003)

CATTOLICI, CHIESA E MAFIA Aspetti storici, politici e religiosi Convegno di Studi (Università di Messina, 27-29 novembre 2003) Giovedì 27 novembre (Aula Magna dell’Università), ore 9:30 Inaugurazione del Convegno Gaetano Silvestri (Magnifico Rettore) Saluti introduttivi S.E. Mons. Giovanni Marra (Arcivescovo di Messina) Francesco Malgeri, (Istituto “Luigi Sturzo”, Roma) Presiede: Guido Pescosolido (Preside Facoltà di Lettere, Università “La Sapienza”, Roma) Angelo Sindoni (Università di Messina) Cattolici e mafia nella storia d’Italia: una questione aperta. Salvatore Cusimano (giornalista RAI, TV, caporedattore, Palermo), Il fenomeno mafioso nella rappresentazione dei mass media. Francesco M. Stabile (Facoltà Teologica, Palermo), Percezione del fenomeno mafioso nell’episcopato siciliano (1948-1970). Berardino Palumbo (Università di Messina), Subcultura mafiosa, religiosità e vita quotidiana nei piccoli centri. S.E. Mons. Michele Pennisi (Vescovo di Piazza Armerina), Pastoralità, ecclesialità e contrasto alla mafia. Giovedì 27 novembre, ore 15:30 Presiede: Agostino Giovagnoli (Università Cattolica, Milano) Francesco Malgeri (Università “La Sapienza”, Roma), Scelba ministro dell’Interno e il fenomeno mafioso. Luigi Masella (Università di Bari), Girolamo Li Causi, Il PCI, la DC e l’analisi della questione mafia. Giovanni Bolignani (Università di Messina), Bernardo Mattarella. Salvatore Butera (Presidente Fondazione Banco di Sicilia, Palermo), Piersanti Mattarella. Angelo Romano (Pontificia Università Urbaniana, Roma), Don Pino Puglisi. Ida Abate (Agrigento), Il giudice Rosario Livatino. S.E. Mons. Gian Carlo Bregantini (Vescovo di Locri), L’educazione alla legalità nella società meridionale. Venerdì 28 novembre (Aula Magna dell’Università), ore 9:30 Presiede: Sergio Zoppi (Università “S. Pio V”, Roma) Agostino Giovagnoli (Università Cattolica, Milano), La DC e la nascita della Commissione Antimafia. -

Le Parole Di Danilo Dolci Anatomia Lessicale-Concettuale

Biblioteca di Educazione Democratica | 1 Michele Ragone Le parole di Danilo Dolci Anatomia lessicale-concettuale Presentazione di Antonio Vigilante Edizioni del Rosone Biblioteca di Educazione Democratica I Michele Ragone Le parole di Danilo Dolci Anatomia lessicale–concettuale Presentazione di Antonio Vigilante Edizioni del Rosone Quest’opera è rilasciata sotto la licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione-Non commerciale-Condividi allo stesso modo 2.5 Italia. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/it Tu sei libero: di riprodurre, distribuire, comunicare al pubblico, esporre in pub- blico, rappresentare, eseguire e recitare quest’opera, di modificare quest’opera alle seguenti condizioni: Attribuzione — Devi attribuire la paternità dell’opera nei modi indicati dall’au- tore o da chi ti ha dato l’opera in licenza e in modo tale da non suggerire che essi avallino te o il modo in cui tu usi l’opera. Non commerciale — Non puoi usare quest’opera per fini commerciali. Condividi allo stesso modo — Se alteri o trasformi quest’opera, o se la usi per crearne un’altra, puoi distribuire l’opera risultante solo con una licenza identica o equivalente a questa. Edizione: marzo 2011 Edizioni del Rosone, via Zingarelli, 11 - 71121 Foggia www.edizionidelrosone.it Stampa: Lulu.com ISBN 978-88-97220-19-0 Agropoli, febbraio 2010 Questo lavoro è dedicato agli Amici che nel ricordo di Danilo continuano un dialogo mai interrotto. A loro tutti pure sono debitore. Presentazione Dopo decenni di un oblio che dice molto sul degrado morale e civile di questo paese cominciano ad avvertirsi i primi segni di una riscoperta dell'opera di Danilo Dolci. -

Capitolo II. La Mafia Agricola

Senato della Repubblica — 133 — Camera dei Deputali LEGISLATURA VI — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI - DOCUMENTI CAPITOLO SECONDO LA MAFIA AGRICOLA SEZIONE PRIMA dell'intimidazione e della violenza, e quello di neutralizzare il potere formale e di pie- LA MAFIA NELLA SOCIETÀ AGRARIA garlo, nei limiti del possibile, ad assecon- dare i suoi privilegi. In effetti, se la mafia si caratterizza come un potere informale, so- 1. Le tre fasi della mafia. no proprio i 'suoi rapporti col potere pub- blico e, in termini concreti, con i suoi tito- L'indagine storica tentata nelle pagine lari a costituirne l'aspetto più rdlleyaiite e al precedenti dovrebbe aver messo in tutta tempo stesso più inquietante. Ciò è tanto evidenza come la mafia sia nata e si sia af- vero che l'opinione pubblica, con l'istintiva fermata, infiltrandosi in quelle zone del tes- sensibilità che la guida nella valutandone di suto sociale, in cui il potere centrale dello quei fenomeni sociali che possono mettere Stato non era riuscito, nemmeno dopo l'av- in pericolo la sicurezza e la tranquilla con- vento del regime democratico, a fare accet- vivenza della collettività, avverte chiaramen- tare la propria presenza dalle comunità lo- te come il nodo da sciogliere, per avviare cali e a realizzare un'opportuna coincidenza a soluzione un problema angoscioso come tra la sua morale e quella popolare. In que- è quello della mafia, si trovi appunto negli ste zone di franchigia delle istituzioni, in atteggiamenti che la mafia ha assunto, nel cui lo Stato ha saputo soltanto sovrapporre corso del tempo, di fronte ai pubblici poteri LI proprio sistema a quello suboultarale vi- e più in particolarie nell'intreccio di [relazio- gente, senza iperò riuscire a fonderli in un ni e di legami che essa ha stabilito (o ha cer- rapporto di stimolante unità, le azioni della cato di stabilire) con gli uomini della poli- mafia hanno sempre avuto lo scopo — co- tica e dell'apparato pubblico, a livello na- me già dovrebbe risultare da quanto fin qui zionale e locale.