INTRODUCTION This Third Volume of Our Study Has a Good Chance, We Think, of Holding the Attention of the Reader -- And, Indee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule and Foundational Documents

Rule and Foundational Documents Frontispiece: facsimile reproduction of a page—chapter 22, “Rules Concern- ing the Good Order and Management of the Institute”—from the Rule of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the 1718 manuscript preserved in the Rome archives of the Institute. Photo E. Rousset (Jean-Baptiste de La Salle; Icono- graphie, Boulogne: Limet, 1979, plate 52). Rule and Foundational Documents John Baptist de La Salle Translated and edited by Augustine Loes, FSC, and Ronald Isetti Lasallian Publications Christian Brothers Conference Landover, Maryland Lasallian Publications Sponsored by the Regional Conference of Christian Brothers of the United States and Toronto Editorial Board Luke Salm, FSC, Chairman Paul Grass, FSC, Executive Director Daniel Burke, FSC William Mann, FSC Miguel Campos, FSC Donald C. Mouton, FSC Ronald Isetti Joseph Schmidt, FSC Augustine Loes, FSC From the French manuscripts, Pratique du Règlement journalier, Règles communes des Frères des Écoles chrétiennes, Règle du Frère Directeur d’une Maison de l’Institut d’après les manuscrits de 1705, 1713, 1718, et l’édition princeps de 1726 (Cahiers lasalliens 25; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1966); Mémoire sur l’Habit (Cahiers lasalliens 11, 349–54; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1962); Règles que je me suis imposées (Cahiers lasalliens 10, 114–16; Rome: Maison Saint Jean-Baptiste de La Salle, 1979). Rule and Foundational Documents is volume 7 of Lasallian Sources: The Complete Works of John Baptist de La Salle Copyright © 2002 by Christian Brothers Conference All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Control Number: 2002101169 ISBN 0-944808-25-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-944808-26-3 (paper) Cover: Portrait of M. -

Understanding Iqbal's Educational Thought

Understanding Iqbal’s Educational Thought Fareeha Nudrat ∗ & Muhammad Saeed Akhtar ∗∗ Abstract The paper presents an overview of Iqbal’s philosophy and its application to educational process. His philosophy has tremendous significance not only for Pakistan educational system, but for the entire world. The nucleus of Iqbal’s philosophy on which the whole educational process builds, is the concept of self-identity (khudi) that strengthens the individual’s innate powers to realize his full potentials towards goodness. His theory of education is subordinated to his fundamental philosophical thought rooted in Islam that (i) ultimate reality is Allah (swt); (ii) ultimate source of knowledge is revelation (wahi); and (iii) ultimate value is unconditional surrender before the will of Allah (swt). As the paper is aimed to provide only some glimpses of Iqbal’s educational thought in an outline form, it warrants a comprehensive and detailed study on the reconstruction of educational thought in the context of Iqbalian philosophy. Key words: Philosophy, Educational Theory, Educational Process Introduction Iqbal is not only a renowned thinker on education; he, in fact, practiced his thought. He taught in the institutions of higher learning both in the sub-continent and European world. His contribution as an active member of All India Mohammadan Educational Conference, ‘ Anjaman-e-Himayat-e-Islam’ , Punjab Educational Conference, and other educational forums further established him as an eminent educationist. 1 Saiyidian, an eminent educationist and a pioneer researcher on Iqbal’s educational philosophy rightly observed that, “I do hope that educationists in India and Pakistan, who are seriously exercised about the problem of educational reconstruction in their countries will give thoughtful consideration to rich contribution which Iqbal can make to our ∗ Fareeha Nudart, PhD Scholar (Education), Institute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore. -

N° 7-2 Juillet 2009

N° 7-2 PREFECTURE DU JURA JUILLET 2009 I.S.S.N. 0753 - 4787 Papier écologique 8 RUE DE LA PREFECTURE - 39030 LONS LE SAUNIER CEDEX - : 03 84 86 84 00 - TELECOPIE : 03 84 43 42 86 - INTERNET : www.jura.pref.gouv.fr 566 DIRECTION REGIONALE DE L’INDUSTRIE, DE LA RECHERCHE ET DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT DE FRANCHE-COMTE .........................................................................................................................................................................................................................567 Arrêté n° 09-123 du 13 juillet 2009 portant subdélégation de signature ................................................................................................567 DIRECTION DEPARTEMENTALE DE L’EQUIPEMENT ET DE L’AGRICULTURE .....................................................................569 Commission départementale de la chasse et de la faune sauvage - Formation spécialisée dégâts de gibier - Compte rendu de la réunion du 10 juillet 2009 .....................................................................................................................................................................................569 Arrêté préfectoral n° 2009/472 du 29 juin 2009 portant création d’une réserve de chasse et de faune sauvage sur le territoire de l’ACCA de VILLERS ROBERT ................................................................................................................................................................570 Arrêté préfectoral n° 2009/473 du 29 juin 2009 portant création d’une -

Science Education at the Stage of Compulsory Education in Japan

Science Education at the Stage of Compulsory Education in Japan Introduction What is required of us is to more reliably cultivate the competencies in children which will allow them to live independently in this unpredictable future society and to participate in the formation of this society. Since 1945, after the end of World War II, Japanese education has faced changes in the times, has incorporated these changes while paying close attention to the situation, and has constantly striven for improvement. While “Japanese-style school education”, which nurtures children’s knowledge, morals, and physical well-being in an integrated manner, has been steadily producing results according to international surveys, there have also been some issues. Focusing on science education at the stage of compulsory education in Japan, we will describe the changes in the courses of study, the current state of children’s academic ability and awareness, and the future direction as seen from the new courses of study. 1. Changes in the courses of study The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) 1 sets the “courses of study” – the standards based on which the schools organize their curriculum pursuant to the School Education Act and other laws so that no matter where a child receives education in Japan, he or she will be able receive a certain level of education. The courses of study are revised about once every 10 years, and they set the objectives and overall educational contents for each educational stage at elementary school and lower secondary school2. In addition, the Ordinance for Enforcement of the School Education Act stipulates the standard number of class hours per year for subjects taught in elementary and lower secondary schools3. -

Le Réseau MOBIGO Dans Le Jura

Le réseau MOBIGO dans le Jura conditions de circulation Dernière mise à jour : 4/4/19 8:40 P = circuit Primaire, retard ou Ne circule Ligne transporteur Origine / destination normale Observations Type de circuit S = circuit Secondaire, perturbée pas (P / S / LR) LR = ligne structurante TOTAUX 286 1 7 100 TRANSDEV / ARBOIS TOURISME Navettes DOLE 1 160 TRANSDEV TAXENNE - GENDREY 1 161 TRANSDEV La BARRE-La BRETENIERE-ORCHAMPS Primaire 1 162 TRANSDEV RPI SERMANGE - GENDREY 1 163 TRANSDEV Ecole Concordia RANCHOT 1 164 TRANSDEV RPI PAGNEY - OUGNEY - VITREUX primaires 1 165 TRANSDEV BRANS - THERVAY - Gpe Sco DAMMARTIN 1 166 TRANSDEV CHAMPAGNEY - RPI Scolaire Dammartin 1 167 TRANSDEV RPI MONTMIREY-OFFLANGES - MOISSEY 1 168 TRANSDEV RPI PEINTRE MONTMIREY 1 169 TRANSDEV RPI PLUMONT - ETREPRIGNEY 1 170 TRANSDEV Pt MERCEY-DAMPIERRE-FRAISANS Prim/Collèg 1 172 TRANSDEV ORCHAMPS - FRAISANS Collège 1 173 TRANSDEV LA BARRE - FRAISANS Collège 1 174 TRANSDEV DAMPIERRE-FRAISANS Prim et collège 1 175 TRANSDEV MONTEPLAIN - ORCHAMPS 1 176 TRANSDEV OFFLANGES - PESMES Collège 1 177 TRANSDEV PAGNEY - PESMES Collège 1 178 TRANSDEV DAMMARTIN Champagnolot - PESMES Collège 1 179 TRANSDEV OUR - FRAISANS Collège 1 180 TRANSDEV RANS - ORCHAMPS 1 210 KMJ FROIDEVILLE - LONS LE SAUNIER 1 211 KMJ MOLAY - TAVAUX Collège 1 212 KMJ ST GERMAIN LES ARLAY - BLETTERANS Collèg 1 213 KMJ CHAPELLE-VOLAND - BLETTERANS Collège 1 214 KMJ FONTAINEBRUX-BLETTERANS Collège 1 215 KMJ BOIS DE GAND - BLETTERANS 1 216 KMJ COSGES - BLETTERANS 1 217 ARBOIS TOURISME BALIASEAUX - CHAUSSIN Collège -

8. 2. 90 Gazzetta Ufficiale Delle Comunità Europee N. C 30/35

8. 2. 90 Gazzetta ufficiale delle Comunità europee N. C 30/35 Proposta di direttiva del Consiglio del 1989 relativa all'elenco comunitario delle zone agrìcole svantaggiate ai sensi della direttiva 75/268/CEE (Francia) COM(89) 434 def. (Presentata della Commissione il 19 settembre 1989) (90/C 30/02) IL CONSIGLIO DELLE COMUNITÀ EUROPEE, considerando che la richiesta di cui trattasi verte sulla classificazione di 1 584 695 ha, di cui 8 390 ha ai sensi visto il trattato che istituisce la Comunità economica dell'articolo 3, paragrafo 3, 1511 673 ha ai sensi europea, dell'articolo 3, paragrafo 4 e 64 632 ha ai sensi dell'articolo vista la direttiva 75/268/CEE del Consiglio, del 28 aprile 3, paragrafo 5 della direttiva 75/268/CEE; 1975, sull'agricoltura di montagna e di talune zone svantaggiate (*), modificata da ultimo dal regolamento considerando che i tre tipi di zone comunicati alla (CEE) n. 797/85 (2), in particolare l'articolo 2, paragrafo 2, Commissione soddisfano le condizioni di cui all'articolo 3, paragrafi 4 e 5 della direttiva 75/268/CEE ; che, in effetti, il vista la proposta della Commissione, primo tipo corrisponde alle caratteristiche delle zone montane, il secondo alle caratteristiche delle zone svantag visto il parere del Parlamento europeo, giate minacciate di spopolamento, in cui è necessario considerando che la direttiva 75/271/CEE del Consiglio, conservare l'ambiente naturale e che sono composte di del 28 aprile 1975, relativa all'elenco comunitario delle terreni agricoli omogenei sotto il profilo delle condizioni zone -

Carte Touristique Pays Du Jura

Maison Pasteur/CIVJ, - Création et réalisation : rectoverso communication - Impression : Est Imprim rectoverso communication - Impression : - Création et réalisation : Maison Pasteur/CIVJ, Maison de la Haute Seille/CIVJ, Philippe Bruniaux/CIVJ, Albisser Hund/CDT Jura, Claudia Hendrick Monnier/CIVJ, Tourisme, Vision/Jura Studio Xavier Servolle/CIVJ, Tourisme, Stéphane Godin/Jura Waltefaugle/Orbagna, Nicolas : Verso Denis Maraux/CDT Jura Jean-Loup Mathieu/CDT Jura, Shutterstock, Tourisme, Michel Loup/Jura Tourisme, Stéphane Godin/Jura Recto : Edition 2015 - Crédit photos : www.jura-vins.com www.jura-tourism.com 2 Salins-les-Bains 8 Nozeroy 9 Haute Vallée de la Saine 10 Les Cascades du Hérisson 11 Le Lac de Vouglans L’Échappée Jurassienne à Foncine et le Lac de Chalain Itinéraire des grands sites du Jura Conseil général du Jura. du général Conseil soutien financier du du financier soutien Cet itinéraire de randonnée du Jura relie la plaine aux hauteurs du massif. Ses 300 Jura Tourisme avec le le avec Tourisme Jura km de sentiers pédestres balisés et homologués (GR®) permettent de découvrir Document réalisé par par réalisé Document la richesse de ce territoire et ses trésors inattendus… Chacun peut se créer son [email protected] Entre deux forts Colline éternelle Le spectacle de l’eau ! Plongées en eaux claires Le géant d’émeraude propre programme de randonnée sur l’Echappée Jurassienne, de 2 à 14 jours à la Tél. 03 84 66 26 14 26 66 84 03 Tél. carte, selon ses envies, son niveau de marche, et la durée de son choix… Et pour 39600 ARBOIS 39600 Prenez un site naturel exceptionnel - le fond d’une grande « reculée ». -

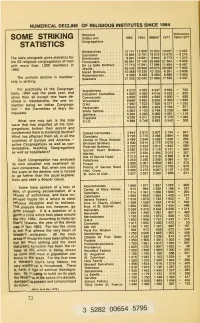

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Superiors General 1952-1988 Brothers Josaphat 1952-1964 Iii

BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 I II SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 III BROTHERS OF THE SACRED HEART SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 Br. Bernard Couvillion, S.C. ROME 2015 IV SUPERIORS GENERAL 1952-1988 BROTHERS JOSAPHAT 1952-1964 V INTRODUCTION With great joy I present to all the partners in our mission – brothers, laypeople, and others – the history of our Superiors Gen- eral during the period from 1952 to 1988: Brothers Josaphat (Joseph Vanier), Jules (Gaston Ledoux), Maurice Ratté and Jean- Charles Daigneault. This history is meant as a remembrance, a grateful recognition, and an encouragement. In the first place, it is meant as a remem- brance, profoundly rooted in our spirit and in our heart, full of es- teem toward each one of them. We remember them especially for their human and spiritual greatness and their closeness to God. We recall their remarkable service of authority in the animation of their brothers and in the revitalization of the prophetic mission of our In- stitute on behalf of young people, particularly those most in need. Calling to mind the lives and the works of our brothers, we thank the God of all goodness for the magnificent gifts which he placed in each of them. In doing so, we recognize the evangelical wisdom of our protagonists, who throughout their life knew how to multiply the talents they had received. Our brothers experienced the joy of feeling loved by God. He wanted them to know the depth of his divine love toward all hu- manity and toward each one of them personally. -

Analyzing ICT Policy in K-12 Education in Sudan (1990-2016)

http://wje.sciedupress.com World Journal of Education Vol. 7, No. 1; 2017 Analyzing ICT Policy in K-12 Education in Sudan (1990-2016) Adam Tairab1 & Huang Ronghuai1,2,* 1School of Educational Technology, Beijing Normal University, 19 Xinjiekouwai Street, Haidian District, Beijing 100875, China 2Smart Learning Institute, Beijing Normal University, 19 Xinjiekouwai Street, Haidian District, Beijing 100875, China *Correspondence: School of Educational Technology, Beijing Normal University, 19 Xinjiekouwai Street, Haidian District, Beijing 100875, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 3, 2016 Accepted: January 7, 2017 Online Published: February 17, 2017 doi:10.5430/wje.v7n1p71 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/wje.v7n1p71 Abstract The aim of this study of ICT policy in K-12 education in Sudan is to investigate the status of planning for technology in education and then determine how the advantage of ICT can best serve the educational system and improve educational outcomes. The study examined two plans for ICT in education, addition to an interview with the educational planning manager, and information center of federal ministry of general education, and other documents from the ministry of education, as well as recommendations of previous studies which emphasized the need for policy to be compatible with other countries may face semi conditions of Sudan, and importance of compatible with UNESCO declarations (Incheon& Qingdao, 2015). The results of this study showed the need for policy emphasis on using technology in education, K-12 education in Sudan requires better technology equipment, inclusive ICT policy includes primary and secondary education need to formulate. The study also suggests that evaluation and assessment are required in order to get more effective solutions and cope with the international educational progress of ICT in K-12 education. -

Liste Des Communes Par Bureau De L'enregistrement

Archives départementales du Jura Liste des communes comprises dans le ressort de chaque bureau de l’Enregistrement dans le département du Jura de 1790 à 1955 Arbois Abergement-le-Grand, Arbois, Les Arsures, Certemery, Chamblay, Champagne-sur-Loue, La Chatelaine, Cramans, Ecleux, La Ferté, Grange-de-Vaivre, Mathenay, Mesnay, Molamboz, Montigny-lès-Arsures, Montmalin, Mouchard, Ounans, Pagnoz, Les Planches-près-Abois, Port-Lesney, Pupillin, Saint-Cyr-Montmalin, Vadans, Villeneuve-d’Aval, Villers-Farlay, Villette-lès-Arbois. Arinthod (rattaché au bureau de Lons-le-Saunier en 1934) Arinthod, Aromas, La Boissière, Céffia, Cernon, Cézia, Charnod, Chatonnay, Chemilla, Chisséria, Coisia, Condes, Cornod, Dramelay, Fetigny, Genod, Legna, Marigna-sur-Valouse, Saint-Hymetière, Savigna, Thoirette, Valfin-sur-Valouse, Vescles, Viremont, Vosbles. Beaufort 1819 – 1942 (avant 1819 voir Cousance ; rattaché àau bureau de Lons-le-Saunier en 1942) Arthenas, Augea, Augisey, Beaufort, Bonnaud, Cesancey, Cousance, Gizia, Grusse, Mallerey, Maynal, Orbagna, Rosay, Rotalier, Saint-Laurent-La-Roche, Sainte-Agnès, Vercia, Vincelles. Bletterans Arlay, Bletterans, Bois-de-Gand (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Brery (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Chapelle-Voland, La Charme (avant 1945 voir Sellières), La Chassagne (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Chaumergy (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Chêne-Sec (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Commenailles (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Cosges, Darbonnay (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Desnes, Les Deux-Fays (avant 1945 voir Sellières), Fontainebrux, Foulenay -

CONTRAT Agir Ensemble AIN AMONT RIVIÈRE

LES DIFFÉRENTES PHASES POUR L’ÉLABORATION D’UN CONTRAT DE RIVIÈRE Contenu du dossier Rédaction du dossier sommaire de candidature, • Diagnostic du bassin versant validé et approuvé par les élus • Définition des enjeux et objectifs ONTRAT • Etudes complémentaires à prévoir C Agrément préalable par le Comité d’Agrément du bassin Rhône Méditerranée RIVIÈRE Composition du Comité de rivière AIN AMONT Afin de garantir une large concertation, le comité Constitution du Comité de rivière de rivière regroupe l’ensemble des acteurs du bassin versant que sont les représentants des collectivités territoriales, des services de l’Etat, des établissements publics, des chambres consulaires, des usagers (industriels, agriculteurs, pêcheurs…), Instance de suivi et de validation de la démarche des associations de protection de la nature… La composition de cette instance est fixée par un Agir ensemble arrêté préfectoral. Durée en moyenne de 2 à 4 ans en moyenne Durée > Protéger Ce dossier précise les objectifs du contrat, les moyens pour les atteindre, le programme Rédaction du dossier définitif d’actions qui en découle, les acteurs concernés > Restaurer et les financements mobilisés pour chaque action. > Valoriser les rivières de l’Ain amont Agrément définitif par le Comité d’Agrément et signature du contrat de rivière OÙ EN SOMMES-NOUS SUR L’AIN AMONT ? Le Conseil Général du Jura proposera le dossier sommaire de candidature au Comité d’Agrément au cours Mise en œuvre des actions de l’année 2012. Généralement 5 ans Généralement Pour tous renseignements complémentaires Claire RENAUD Chargée de projet contrat de rivière Conseil Général du Jura Lettre d’infos N°1 Direction du Développement Economique et de l’Environnement Mission Rivières Espaces Naturels Nos Partenaires Jean RENAUD..