Thesis Rests with the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Change: a Consideration of the UK Food Retail Industry, 1950-2010. Phd Thesis, Middlesex University

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Clough, Roger (2002) Retail change: a consideration of the UK food retail industry, 1950-2010. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/8105/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Download (11Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/98784 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 2 o Strategic Groups, Industry Structure and Firms ’ Strategies: Theory and Evidence from the UK Grocery Retailing Industry Francesco Fortunato Curto Thesis Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Warwick Business School University of Warwick England May 1998 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1.0 The Research P- 1 1.1 Structure of the Research P- 5 Chapter 2 The Theoretical Foundations of Strategic Groups: the Harvard Approach 2.0 Introduction P- 9 2.1 The Research Context: Industrial Organisation and the Structure-Conduct-Performance (SCP) Paradigm p. 10 2.1.1 Firms’ Strategies and the Industry Structure in the SCP Paradigm P- 15 2.2 The Theory of Strategic Groups and Mobility Barriers p. 16 2.2.1 Structural and Endogenous Barriers to Entry P- 18 2.2.2 Barriers to Mobility and Strategic Groups P- 20 2.2.3 The Origins of Strategic Groups and Firms’ Strategic Behaviour P- 21 2.2.4 Intergroup Mobility, New Entry and Mobility Dynamics p. 22 2.3 The Characteristics of Strategic Groups Theory P- 25 2.4 Further Theoretical Development: Porter’s (1979) Theory of a Firm’s Profitability P- 28 2.4.1 Oligopolistic Rivalry and Firms’ Performance p. -

JS Journal May 1983

V sale, Woman F lO^f BETWEEN WOMEN ry's fresh ww and Slimming hpork. Home Essa usowners.| PfillCESS ALEX 'm A:; j restiil. Samsburys pork Whj shes the greatest , ' V BMBi ruV-jys :-(»;h and in ilk' '-.viy iv;,t : conditK'm : - Ihp mean b pink •rafflUDHOME - * ThebtswhKB •TUtenks '. % k i And the nnd is swmcwhefe |fahBf \^ *> ,. hei:wecn.!TohelpyTxicarwthe ; !^ki:.'y voLi'ii Unci ui;i jtjints cor RVETBEGRE/ff vX,rseiJporki< v-h ! ; and joints with the hone . J r • ili^r All (.wfrvrly ainsi Good food costs te aoiof forFarmahara •utitisrft a conversation.) What is it • ftu, you can also use it in rout WelUts^tehasr^lescnbec! Jads or as a puree to add to.ee cream. a mixture of apricot f~ iu like, in a mousse Though many I i A ~--—--~-~JkaMss; than either. ?Sain5buiy£ovm xvrbuiSeis- WJO'S n With 0% beef ingto astral ia then? MS *»*>?• m put our S ^attention to 3ood fonn ' "° ?ne has to beef GOOD IvS- THE COMPLETE tmrm $ *can improve! 1 your f complexion overnights ' TWO GREAT ^*-C^ NEWS NEWS NEWS Agood Stilton from Sainsburys will make Advertising your mouth water. awards (Not your eyes.) 'ith ,i strong And we have strict ••;. been associating amoun; of bl;i(';iii; we'll accept. Sntam At this time of yeat we sell Stilton i JS ADVERTISING was up on the uid have ;••• mellow |ais. halve:-1, and quarters, though perhaps winners' rostrum again last month when a popubi size is the Stilton di : should explode from ie picture, Campaign magazine, the advertising eheese but not quite reach yone ixi'vV jstd it will Keephappriy industry's top publication, announced the recipients of its annual Press Awards. -

Retail Supermarket Globalization: Who’S Winning?

RETAIL SUPERMARKET GLOBALIZATION: WHO’S WINNING? October 2001 CORIOLISRESEARCH Coriolis Research Ltd. is a strategic market research firm founded in 1997 and based in Auckland, New Zealand. Coriolis primarily works with clients in the food and fast moving consumer goods supply chain, from primary producers to retailers. In addition to working with clients, Coriolis regularly produces reports on current industry topics. Recent reports have included an analysis of the impact of the arrival of the German supermarket chain Aldi in Australia, answering the question: “Will selling groceries over the internet ever work?,” and this analysis of retail supermarket globalization. ! The lead researcher on this report was Tim Morris, one of the founding partners of Coriolis Research. Tim graduated from Cornell University in New York with a degree in Agricultural Economics, with a specialisation in Food Industry Management. Tim has worked for a number of international retailers and manufacturers, including Nestlé, Dreyer’s Ice Cream, Kraft/General Foods, Safeway and Woolworths New Zealand. Before helping to found Coriolis Research, Tim was a consultant for Swander Pace (now part of Kurt Salmon) in San Francisco, where he worked on management consulting and acquisition projects for clients including Danone, Heinz, Bestfoods and ConAgra. ! The coriolis force, named for French physicist Gaspard Coriolis (1792-1843), may be seen on a large scale in the movement of winds and ocean currents on the rotating earth. It dominates weather patterns, producing the counterclockwise flow observed around low- pressure zones in the Northern Hemisphere and the clockwise flow around such zones in the Southern Hemisphere. It is the result of a centripetal force on a mass moving with a velocity radially outward in a rotating plane. -

A Master Grocers Life This Is a Picture of the Shop Approximately 100 Years Ago As a Two Storey Building with No Large Windows on the Front of the House

A Master Grocers Life This is a picture of the shop approximately 100 years ago as a two storey building with no large windows on the front of the house. It belonged to William Barr, Grocer next door to the Commercial Hotel. William Barr set up the Barr Trust for many poor people of Kirkcudbright. At one time this was run by the Town Council and then the Community Council and it is now part of the Common Good Fund. My Father was a grocer, man and boy, with James McMeekan in Castle Douglas. The shop was where the Douglas Arms bar is now, across from the Town Clock in King Street. As he was in the R.A.F. reserve he was called up early in the 1939 for the war effort. He returned to the shop as manager in 1946 . In 1953 Mrs Clingan, in Kirkcudbright, was looking for a new manager. Word soon reached my Father through the many company reps there were on the road. He applied and was given the post. From 1953, till after the death of Mrs Clingan, in early 1959, Father travelled daily on his motor bike from Castle Douglas. Meanwhile, my twin brother Michael and myself having left school at 15, were both serving a four year apprenticeship in engineering. Following the death of Mrs Clingan, her family decided to sell the business and offered Dad the first chance to purchase! William Smart the baker in Castle Douglas offered to join Father as a sleeping partner, so the deal was done and Father and Mother took over on 28th June 1959. -

The Effect of Organizational Processes on the Strategy to Introduce New Technology Into Retailing

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL PROCESSES ON THE STRATEGY TO INTRODUCE NEW TECHNOLOGY INTO RETAILING Submitted By CATHERINE J. CROMBLEHOLME in fulfilment of the requirement for the Doctor of Philosophy DURHAM UNIVERSITY BUSINESS SCHOOL JULY 1988 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. .- 6 JUL 1989 ABSTRACT THE EFFECT OF ORGANIZATIONAL PROCESSES ON THE STRATEGY TO INTRODUCE NEW TECHNOLOGY INTO RETAILING Despite the widespread changes that are taking place in retail technology, it is an area which 'has been subjected to relatively little research. In particular, there has been a neglect of the process of introducing new technology. Based on a comparative study of two supermarket chains, this thesis examines the way in which technology is introduced into retail companies and the problems they encounter. The technology in question consisted of the computerisation of all head office and warehouse systems and the introduction of Electronic Point of Sale (EPOS) and Portable Data Capture Units (PDCs) into the branches. Research methods included participant observation, interviews and analysis of documents. The study found that the introduction of new technology was not the result of a rational, pre-determined strategy, but that it evolved from a series of ad hoc decisions. Organizational processes played an important part in forming this emerging strategy and also influenced its successful implementation. -

Socio-Spatial Variations in Urban Food Price and Availability and Their Implications for Healthy Eating

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Socio-spatial variations in urban food price and availability and their implications for healthy eating Steven C J Cummins Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit December 2001 © Cummins 2001 ProQuest Number: 10646390 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uesL ProQuest 10646390 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

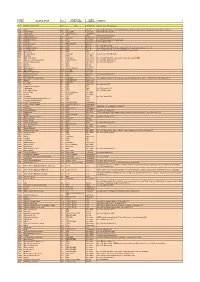

ANMW Retail Multiple Classifications

ANMW ANMW RETAIL ANMW MULTIPLE GROUP Status COMMENTS CODE CLASSIFICATIONS CATEGORY AFS Amazon Fresh Stores Live CON Convenience Code live from 16th Jul 2021 ALD Aldi Live SUP Grocery Live 21st November 2011 - from 13th April 2015 - Class from MIS to SUP, Category from Other RMG to Grocery ALE Aleef Garages Live CFC / SER Forecourts Revived 7th February 2011 AFJ Alfred Jones Live CON/CCC/CFC Convenience AAS Alpha Airports Live ITP Travel Revived 28th August 2009 APW Appleby Westwood Live CON/CCC Convenience Live 1st February 2010 APL Applegreen Stores Live CFC Forecourts Live 29th November 2010 - Ireland Only ARA Aramark Live CAP Convenience Live 31st March 2008 ASP Asda Forecourts Live PFC/CFC/SER Grocery ASL Asda Living Live CAP Grocery Live 1st February 2010 ASN Asda Supermarkets Live CCC Grocery Live 29th November 2010 : Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - NETTO ASD Asda Superstores Live SUP Grocery Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - Supermarkets BAN Bailey News Live CTN CTN BES Bestways Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Code live from 16th Mar 2020 BLK Blackwells Live MSN Other RMG TAT Blakemore Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Live from 28th May 2012 - Just a name change previously TATES BRI Blakemore Retail Independents Live CON/CFC/PFC Convenience Live from 20th October 2014 BGC Blooms Garden Centres Live MIS Other RMG Live from 13th March 2017 BTH Booths Live SUP Grocery BOO Boots Plc Live MSN High Street BOU Bourne Leisure Live Refer to class list Other RMG BPC BP Connect Live CFC/SER Forecourts BPS BP M&S Simply -

Spring Retail Report 2018

Spring Retail Report 2018 Diversity First, Retail Second Introduction by Graham Chase Right Space, Right Place In-Town Agency The Return of The Pod Out-of-Town Agency Small Gains, Mergers & Acquisitions Superstores and Supermarkets Retail & Logistics = Rising Rents, Falling Yields Retail & Shopping = Falling Rents, Rising Yields Retail Investment User Mix & Dwell Time Key to Continued Success Leisure 01 Contents “The right new retail 03 Diversity First, Retail Second accommodation in Introduction the right place which 09 Right Space, Right Place draws shoppers In-Town Agency is an important 21 The Return of The Pod ingredient if there Out-of-Town Agency is to be a balance to 25 Small Gains, Mergers & internet trading and Acquisitions the questionable Superstores and Supermarkets sustainability of home Spring 31 Retail & Logistics = Retail Report deliveries.” Rising Rents, Falling Yields Retail & Shopping = Diversity First, Retail Second Falling Rents, Rising Yields 2018 Introduction by Graham Chase Retail Investment 39 User Mix & Dwell Time Key to Continued Success Leisure Introduction 03 Return to Contents Spring Retail Report The Chase & Partners Spring Retail Report is produced annually on about 1st May each year and has been a feature 2018 of the market since C&P commenced trading in 1995. The reports cover both the retail and leisure sectors, both in town Introduction & history of retailing by Graham Chase and out of town, although depending on activity the focus does vary. It is written as an independent commentary on both occupational and investment property market issues Diversity and does not seek to reflect on, or promote, any current instruction or aspirations of a client. -

Social Survey Division Family Expenditure Survey 1997-98 DIARY

Social Survey Division Family Expenditure Survey 1997-98 DIARY QUESTIONNAIRE & Instructions to Interviewers & Editing Notes 1997-98 DIARY Famdy Expenditure Survey TABLE DIARY 105 Id PAB.DONE APPLIES TO ALL Has coding been completed, verd’icahon done ]f requmed, and page 38 keyed? Yes 1 No 2 Nd expenditure both weeks 5 Nd experxhture Week 1 only 6 Nd expenditure Week 2 only 7 TABLE: EXPEND 205 EXPEIW_IternNum APPLIES TO ALL Item (row) number 1 249 t 2010 Itl/It2/It3 Day (*) , APPLIES TO ALL UNLESS PAf_DONE CODED 5 r If entry for a day us diary, key the day number. 1 14 2015 It l/It2/It3 KeyText (EXPEND_KEYTEXTO) APPLIES IF DAY = 1-14 Key text as necessary L. f m,. %cd.& ,, Sc,!emkr ,!78 Page 1 1 1997-98 Diary Famdy Expenddure Survey ) 1 TABLE: EXPEND 2020 Itl/It2/ft3 KeyText code (EXPEND_KEYTEXTl) . APPLIES IF 2015 = RESPONSE Computer-assisted code field , (codes entered from d]ct]onary of expenditure Items, matchmg text keyed at ‘ 20 15) 1 010101 Rent 010102 Mortgage mstalment payment 010103 Mortgage endowment pohcy 010104 Mortgage protection pohcy 010105 Councd tax (GB), Rates (NI) 010106 Water rates 010107 Ser-wce charges 010108 Structural insurance 010109 Contents insurance J 010110 Ground rent . 010201 Outright purchase of/depos]t on masn dwelhng 010202 Caravan and mobde home purchase/decorauon 010301 Central heating ]rrstallat]on 010302 Central heating maintenance 010303 Capital Improvements 010304 Repros, decorations, replacements “4 010401 Central heating mstallatlon J 010402 Double glazing, Iatchen uruts, sheds, etc 010501 Doors, -

Industry Report

INDUSTRY REPORT 2030: THE DEATH OF THE HIGH STREET WHY THE RISE IN E-COMMERCE MEANS BRITAIN’S TOWN CENTRES WILL BE UNRECOGNISABLE WITHIN 15 YEARS AUTHOR: DAVID JINKS MILT HEAD OF CONSUMER RESEARCH EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: PARCELHERO.COM/HIGHSTREETREPORT THE HIGH STREET APPEARS UNCHANGING; BUT IN FACT IT IS AN ENVIRONMENT THAT IS UNDER THREAT. IN 1950 THERE WERE NEARLY 600,000 STORES IN THE UK; BUT, BY 1971, THE ARRIVAL OF THE SUPERMARKET REDUCED THE AMOUNT TO WELL UNDER 400,000. BY 2012 THERE WERE ONLY 290,000 SHOPS LEFT; AND BY 2030 JUST 130,000 ARE LIKELY TO SURVIVE BECAUSE OF THE IMPACT OF E-COMMERCE. NOTE THE BANK LOGO. BANK FASHION FAILED IN 2015 IN THE TEETH OF INTERNET COMPETITION. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The death of the High Street as we know it may be far nearer than people think. By 2030, just 13 years’ time, the impact of e-commerce and home deliveries will mean the town centre as we know it today, with all its familiar names, will be a memory. 1. Vanishing stores: Between 2020 and 2030 half of the UK’s existing shop premises will have disappeared. In 1950 there were 600,000 stores in the UK, in 2012 there were 290,000 and just 220,000 will survive by 2020 says The Centre for Retail Research. With home deliveries increasing exponentially, the decade from 2020 to 2030 will see a further 100,000 stores close if this trend continues: leaving just 120,000 shops on our high street. 2. E-commerce conquers all: By 2030 e-commerce will account for around 40% of all UK retail sales. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2002 Building

Annual Report and Accounts 2002 building Our goal is to be the first choice for those customers who have the opportunity to shop locally in a Safeway store. To deliver this goal we will focus on: – product and price, and be – best at fresh – best at availability and – best at customer service store formats p14 best at fresh p8 best customer service p30 £1.79 89 p best deals p22 best availability p26 Safeway plc Annual Report Solicitors Chairman’s statement 2 Best availability 26 and Accounts 2002 Clifford Chance LLP David Webster summarises Safeway’s Keeping our shelves full throughout the Stockbrokers Contributing editors WestLB Panmure Limited performance during the year and trading day remains a key priority and Kevin Hawkins CSFB de Zoete highlights some of the key our performance goes from strength Simon Laffin & Bevan Limited Miles Collins developments in our industry. to strength. Steve Webb Design and production Janey Berry Addison Safeway Photography Chief executive’s review 4 Best customer service 30 Registered Office Food photography: Our new formats, product ranges, The key to being best at customer service 6 Millington Road Ian O’Leary Hayes, Middlesex Location photography: value offer and the commitment of is to train and motivate our colleagues UB3 4AY Andrew Wilson Safeway people are the themes of better than our competitors – which is 020 8848 8744 Board photography: John Wildgoose Carlos Criado-Perez’s review of the year. exactly what we’re doing. Internet Product photography: www.safeway.co.uk Ben Jennings Group Company Secretary Andrew Wilson Best at fresh 8 Our corporate responsibilities 32 & Legal Director Front cover: Leadership in product standards and We take our responsibilities to all our David Wilson Ian O’Leary innovation is a core brand value of stakeholders very seriously.