© 2016 Andrew Wehmann All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology Fa Ct Or

Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price Origin Label Genre Release A40355 A & P Live In Munchen + Cd 2 Dvd € 24 Nld Plabo Pun 2/03/2006 A26833 A Cor Do Som Mudanca De Estacao 1 Dvd € 34 Imp Sony Mpb 13/12/2005 172081 A Perfect Circle Lost In the Bermuda Trian 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Virgi Roc 29/04/2004 204861 Aaliyah So Much More Than a Woman 1 Dvd € 19 Eu Ch.Dr Doc 17/05/2004 A81434 Aaron, Lee Live -13tr- 1 Dvd € 24 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81435 Aaron, Lee Video Collection -10tr- 1 Dvd € 22 Usa Unidi Roc 21/12/2004 A81128 Abba Abba 16 Hits 1 Dvd € 20 Nld Univ Pop 22/06/2006 566802 Abba Abba the Movie 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 29/09/2005 895213 Abba Definitive Collection 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 22/08/2002 824108 Abba Gold 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 21/08/2003 368245 Abba In Concert 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 25/03/2004 086478 Abba Last Video 1 Dvd € 16 Nld Univ Pop 15/07/2004 046821 Abba Movie -Ltd/2dvd- 2 Dvd € 29 Nld Polar Pop 22/09/2005 A64623 Abba Music Box Biographical Co 1 Dvd € 18 Nld Phd Doc 10/07/2006 A67742 Abba Music In Review + Book 2 Dvd € 39 Imp Crl Doc 9/12/2005 617740 Abba Super Troupers 1 Dvd € 17 Nld Univ Pop 14/10/2004 995307 Abbado, Claudio Claudio Abbado, Hearing T 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Tdk Cls 29/03/2005 818024 Abbado, Claudio Dances & Gypsy Tunes 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 12/12/2001 876583 Abbado, Claudio In Rehearsal 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 23/06/2002 903184 Abbado, Claudio Silence That Follows the 1 Dvd € 34 Nld Artha Cls 5/09/2002 A92385 Abbott & Costello Collection 28 Dvd € 163 Eu Univ Com 28/08/2006 470708 Abc 20th Century Masters -

28, 1926, ?1.50 Per Year

TER. 'fVHt-i Ii«U4d Vffeklf, Entered •• Beeond-dlasa flatter at the Foft* .VOLUME XLVIII, NO. 44. • ofllee at Ked Sank. N. J^ under tbs Act of March 8, 1878. RED BANE,% J., WEDNESDAY, AFREii 28, 1926, ?1.50 PER YEAR. • PAGES f TO 12.,! ACCIDENT ON BROAD STREET. NEW VOCAL STUDIO. WILL GIVE UP BUSINESS. ra ^|HEGB|g||E§TnVAl. HANDSQltfE HOME BURNED Frank Thompion'i Coups D»mag4d 'APER COMPANY MOVES. ormer Metropolitan Singer to A RECORD HARD TO BEAT, IG FIRE IN COAL YARD. 'in a Colliiion Lait Week. Open School Here. DETAILS AREl ARRANGED FOR tUMSON RESIDENCE OF; HOW/ GEORGE WOODS WILL RETIRE NOW OCCUPYING NEW BUILD- JOHN S. STILES HAS AN UN- GILDINGS; •• BURNED- i ON; ;:pf •• W- Miss Joanne VanElton of New •7 TOWN'S;iBi(J~CEtEBRATlONi ARD'S. BORDEf* DESTROYED, A Nash sport car ('riven by Miss AFTER 48 YEARS. ING ON RIVER STREET. ^GJJRDON1^^ PLACEi"A;^'>'ff|i|| Dorothy Gaffcy of Atlantic'High- ork will,open a votiul ituJio in a USUAL ANNIVERSARY. ' i"Bund Mu«lcr Banquet'ond .Various Lous Is Estimated 'at $400,000, But anda and a Ford coupe driven by Ho -will Turn Over hit Sewing Ma- Tlio New Quarters, . With Office!, 'ew.days at 21 Ps^crs.1 plate for Lust Friday Rounded Out 59 Yean am, Shedi and Lumber Deitroyocl V; r^' Ojh«>•Matter* TaWenJJare Of—•_ Some Thing; Logt Woro Price)r«s [•>nnk Thompson of Red Bank-col- chino Bti!ine!i Saturday; to his .Storehouse :mic!--Garag6 All .Un» oico placement, coaching, Italian of Work for Mini a« • Mason— Thursday - 'Af tornoon byr~|[^ Flf«*-f£;& ,! SJy«lUs»p!e"v'CiR»"/ From • Italian. -

The Bloody Nose

THE BLOODY NOSE AND OTHER STORIES A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Emily D. Dressler May, 2008 THE BLOODY NOSE AND OTHER STORIES Emily D. Dressler Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ ___________________________ Advisor Department Chair Mr. Robert Pope Dr. Diana Reep __________________________ ___________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Dr. Mary Biddinger Dr. Ronald F. Levant __________________________ __________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Robert Miltner Dr. George R. Newkome ___________________________ ___________________________ Faculty Reader Date Dr. Alan Ambrisco ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following stories have previously appeared in the following publications: “The Drought,” Barn Owl Review #1; “The Winters,” akros review vol. 35; “An Old Sock and a Handful of Rocks,” akros review vol. 34 and “Flint’s Fire,” akros review vol. 34. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PART I. HELEN……………………………………………………………………………….1 The Bloody Nose……………………………………………………………………......2 Butterscotch………………………………………………………………………….....17 Makeup…………………………………………………………………………………29 The Magic Show………………………………………………………………………..44 The Drought…………………………………………………………………………….65 Important and Cold……………………………………………………………………..77 Someone Else…………………………………………………………………………...89 II. SHORTS…………………………………………………………………………….100 An Old Sock and a Handful of Rocks………………………………………………….101 Adagio………………………………………………………………………………….105 -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-2010 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (2010). Columbia Poetry Review. 23. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 3> 7 25274 82069 6 $10 .00 USA/ $13.00 CANADA columbiapoetryreview no. 23 Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the English Department of Columbia College Chicago, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60605. SUBMISSIONS Our reading period extends from August 1 to November 30. Please send up to 5 pages of poetry during our reading period to the above address. We do not accept e-mail submissions. We respond by February. Please supply a SASE for reply only. Submissions will not be returned. PURCHASE INFORMATION Single copies are available for $10.00, $13.00 outside the U.S but within North America, and $16.00 outside North America. Please send personal checks or money orders made out to Columbia Poetry Review at the above address. You may also purchase online at http://english.colum.edu/cpr. -

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

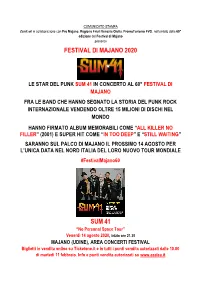

Festival Di Majano 2020 Sum 41

COMUNICATO STAMPA Zenit srl in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismo FVG, nell’ambito della 60° edizione del Festival di Majano presenta FESTIVAL DI MAJANO 2020 LE STAR DEL PUNK SUM 41 IN CONCERTO AL 60° FESTIVAL DI MAJANO FRA LE BAND CHE HANNO SEGNATO LA STORIA DEL PUNK ROCK INTERNAZIONALE VENDENDO OLTRE 15 MILIONI DI DISCHI NEL MONDO HANNO FIRMATO ALBUM MEMORABILI COME “ALL KILLER NO FILLER” (2001) E SUPER HIT COME “IN TOO DEEP” E “STILL WAITING” SARANNO SUL PALCO DI MAJANO IL PROSSIMO 14 AGOSTO PER L’UNICA DATA NEL NORD ITALIA DEL LORO NUOVO TOUR MONDIALE #FestivalMajano60 SUM 41 “No Personal Space Tour” Venerdì 14 agosto 2020, inizio ore 21.30 MAJANO (UDINE), AREA CONCERTI FESTIVAL Biglietti in vendita online su Ticketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita autorizzati dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. Info e punti vendita autorizzati su www.azalea.it Secondo annuncio internazionale per il Festival di Majano, storica rassegna musicale, culturale e enogastronomica del Friuli Venezia Giulia che festeggia nel 2020 i suoi 60° anni attestandosi come una delle manifestazioni più longeve e di successo dell’estate. Dopo il concerto con protagonisti i Bad Religion, i cui biglietti sono andati in vendita nelle scorse settimane, ecco ufficializzato oggi l’arrivo delle star del punk rock mondiale Sum 41, che saranno straordinariamente in concerto sul palco dell’Aera Concerti il prossimo venerdì 14 agosto 2020. I biglietti per questo nuovo grande appuntamento musicale dell’estate, organizzato da Zenit srl, in collaborazione con Pro Majano, Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia, PromoTurismoFVG e Hub Music Factory, saranno in vendita online su Tiketone.it e in tutti i punti vendita del circuito dalle 10.00 di martedì 11 febbraio. -

Anansi Boys Neil Gaiman

ANANSI BOYS NEIL GAIMAN ALSO BY NEIL GAIMAN MirrorMask: The Illustrated Film Script of the Motion Picture from The Jim Henson Company(with Dave McKean) The Alchemy of MirrorMask(by Dave McKean; commentary by Neil Gaiman) American Gods Stardust Smoke and Mirrors Neverwhere Good Omens(with Terry Pratchett) FOR YOUNG READERS (illustrated by Dave McKean) MirrorMask(with Dave McKean) The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish The Wolves in the Walls Coraline CREDITS Jacket design by Richard Aquan Jacket collage from Getty Images COPYRIGHT Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material: “Some of These Days” used by permission, Jerry Vogel Music Company, Inc. Spider drawing on page 334 © by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved. This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. ANANSI BOYS. Copyright© 2005 by Neil Gaiman. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of PerfectBound™. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gaiman, Neil. -

April 11,1879

PORTLAND DAILY ^——————■———I PRESS.■—m»-w————a— ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862.-V0L. 16. FRIDAY MORNING, APRIL 11, 1879. ___PORTLAND, TERMS $8.00 PEIt anmm in T'TTT^ THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS, Cincinnati has tried . BUSINESS CARDS. THE Democratic “free Democratic Publithed every day (Sundays excepted) by the _WANTS ______MISCELLANEOUS.__ PBE8S Difficulties, voting,” and doesn’t want any more of It. PORTLAND PUBLISHING CO. Wanted. The declares in favor of the FRANCIS H. FRIDAY MORNING, APRIL 11. city election laws. LORD, a either as com- A AT 109 ExtJHAKflB Pobtlxsd. some Christian family, position Define of the Ilard-.TIanry Tim—The St., aDd as-istant to an invalid mother or as IN panion Eureka Tunnel and The Democrats are to D a a refined, intelligent Best do not read beginning trem- Eavtrra' ing Routed—Elation of Terms: Bight Dollars Tear. To mail subscribers misery governess, by lady. Mining We anonymous letters un common! thee Company. ble for Seven Dollars a Tear U paid In advance. references given. Address E. S. ROLLINS, Brook- Indiana. They have carried matters ATTORNEY AND cations. The name and address of the writer are Is Cirfrnbartfra, COUNSELLOR, lioe, Mass.apfrdfit* with too Location of Aline g : 1STevada. all oases indispensable, not necessarily for high a hand ont there. THE MAINE STATE PRESS 23 Court Boston. EUREKA, publication Street, hot as a guaranty of good faith. TbejWaehiogton correspondent of the Boa- Is Thursday Morning at a The are published every $2.C0 We cannot undertake to return ot ministers giving the lie at ^‘“Particular attention given to collection?. -

THE BLACK RAP B.S.A.'Snewspaper

THE BLACK RAP B.S.A.'sNEWSPAPER Realizing that the BUILDING of A Black NATION depends on the Strength of the Black MIND, B.S.A. wishes to commend these Brothers & Sisters for their achievements in academic excellence. The following Brothers & Sisters, alphabetically list ed, attained grade point average*of 4.000 or above during the Spring Semester of 1969: 61. Hogan, Dean 62. Hose, Judith ? 63. Sampson, Leilie 64. Tins, Jeanette 65. Thornton, Michael 66. Tankeraley, Joseph 67. Sullivan, Marshall 68. Stingley, Dana 69. Stewart, Robert f> 70. Stanton, Lavatta 71. Spencer, gthelda 72. Smith, Yolanda 73* imaw, Alonzo 1. Alderman, Brenda 31. Hill, John C. l k . Smart, Barbara 2. Allen, Constance 32. Hill, Kathleen 75* Shelton, Rosalind 3 . Bailey, Beverly 33• Howard, Patricia 76. Wage, Willie 4. Baker, Felix 34. Jackson, Andrew 77. Walker, Joe 5. Barnes, Gary 35. Jackson, Aretha 78. Wallace, Judith 6. Bell, William D. 36. Jackson, Valerie 79* Walton, Lamont 7. Bostic, Victoria 37. Jasmick, Adam £. Brandon, Otha L. 38* Karanusic, Maya 80. Wiggins, Jerome 9 . Brown, Vernade&n 39. Karnett, Renee 81. Williams, Lawrence 10. Campbell, Jaaes to. King, Gertrude 82. Wilson, Michael 83. Winley, Ronald ? 11. Clay, gloria to. Ledbetter, Rosetta 84. Withers, Rosalyn 12. Cleveland, John k2. Lopez-Ccles, Carles 85. Wright, Carlotta 13. Clifton, Jennifer to* McClellan, Leonard . Wright, Richard 14. Coe, Rocky L. to. McClendon, Yvette 86 15. Cole, Gwendolyn to. McCray, Donnell A 16. Coleman, Diane k6 . McGee, Darlene ? 17. Dawson, Carlee to. McNair, Leonard Continued from page lO 18. Druramings, Harriet 48. Moy, May a) dietary information 19. -

L(Ie Newark ·P.Ost

l(ie Newark ·P.ost ~TO LU ME XVI . NEWARK, DELAWARE. MAY 20, 1925. NUMBER 16 = Suggest Plans For HIGH SCHOOL SENDS TAX COLLECTORS ARE Student Election OUT 32 GRADUATES ALL APPOINTED BY COURT Preservation Commencement Exercises to Colmery Suc<:eeds Edmanson .Interrupted By Of Citizens Academy Building Be Held In Wolf. Hall, In Whi,te Clay Creek Hun "C om b·Ine "Ch arge Friday, June 12th of dred; T'erms Are For' Famou Old Structure May Become Thirty-two boys and girls will be Two Years Sigma Phi Epsilon Members Walk THe State of Delaware Community Center if Preliminary graduated from Newark High School At the weekly meeting of the New Out of Wolf Hall During Ballotting Plans Take Shape; Committee next month, according to the official Castle County Levy Court yesterday list obtained this week from Superin- Are invited to attend the Exercises of Dedication morning the following tax collectors Yesterday; Will Investigate [0 Feel O~ent of Town tendent Owens. This compri'ses one were appointed to serve the several Allegations hundreds for two years, beginning TEES CANNOT FINANCE IT of the largest classes in the history TRUS of the Memorial Library at the University of June 1: of the school. .. Appoquinimink hundred, Benjamin SERIOUS EFFECTS ARE SEEN Lockermon, of near Blackbird, to 1'llo' first move destined to affect The list of graduates follows: Delaware on Saturday afternoon, May 23, 2.30 the fulure of t he famous old Newark Agnes Frazer, Dorothy Blocksom succeed George S. Rh lems; Blackbird With a roar ~hat figuratively shook the student body to its heels, the lid A rad~I1IY bu ilding was ma.?e Thurs- Mary Rose, Erica Grothenn, Eliza hundred; George D . -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother. -

Sleepers 1996

Rev. 6/6/95 {Blue) Rev. 7/31/95 ("Pin.kl Rev. 8/14/95 {Yellow) Rev. 8/18/95 {Green) Rev'. 8/29/95 {Goldenrod) Rev. 8/30/95 {Buff) SLEEPERS screenplay by Barry Levinson based on the book by Lorenzo Carcaterra April 14, 1995 SCREEN IS BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION I sat across the table from the man who had battered and tortured and brutalized me nearly thirty years ago. Al FADE IN Al TIGHT SHOT of a MAN'S face in shadow. The room is dimly-lit and we can't make out where we are. MAN I don't know what you want me to s.ay. I didn't mean all those things. None of us did. ADULT SHAKES O/C I don't need you to be sorry. It doesn't do me any good. MAN I'm begging you ... try to forgive me. Please ... try. ADULT SHAKES O/C Lea= to live with it. MAN I can't. Not any more. ADULT SHAKES 0/C Then die with it, just like the rest of us. FADE TO BLACK LORENZO'S NARRATION This is a true story about friendship that runs deeper than blood. FADE UP 1 INT. GYM - EVENING J. * The gym is full of BOYS and GIRLS between the ages of 9 and J.3. They're dancing in a 'twist' competition while a DJ plays records. However, there is no so1md, and the film is slightly slowed down, making the movements a little e'1<:aggerated. LORENZO'S NARRATION This is my story, and that of the only three friends in my life who truly mattered.